'The Masters Are Close to an Isolated Lodge' : the Theosophical Society In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett The Early Days of Theosphy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1922 NOTE [Page 5] Mr. Sinnett's literary Executor in arranging for the publication this volume is prompted to add a few words of explanation. There is naturally some diffidence experienced in placing before the public a posthumous MSS of personal reminiscences dealing in various instances with people still living. It would, however, be impossible to use the editorial blue pencil without destroying the historical value of the MSS. Mr. Sinnett's position and associations with the Theosophical Society together with his standing as an author in the Theosophical movement alike demand that his last writing should be published, and it is left to each reader to form his own judgment as to the value of the book in the light of his own study of the questions involved. Page 1 The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett CHAPTER - 1 - NO record could truly be called a History of the Theosophical Society if it concerned itself merely with events taking shape on the physical plane of life. From the first such events have been the result of activities on a higher plane; of steps taken by the unseen Powers presiding over human evolution, whose existence was unknown in the outer world when their great undertaking — the Theosophical Movement — was originally set on foot. To those known in the outer world as the Founders of the Theosophical Society — Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott — the existence of these higher powers, The Brothers as they were called at first, was more or less imperfectly comprehended. -

Vol142no04 Jan2021

Text of Resolutions passed by the General Council of the Theosophical Society Freedom of Thought As the Theosophical Society has spread far and wide over the world, and as members of all religions have become members of it without surrendering the special dogmas, teachings and beliefs of their re- spective faiths, it is thought desirable to emphasize the fact that there is no doctrine, no opinion, by whomsoever taught or held, that is in any way binding on any member of the Society, none which any member is not free to accept or reject. Approval of its three Objects is the sole condition of membership. No teacher, or writer, from H. P. Blavatsky onwards, has any authority to impose his or her teachings or opinions on members. Every member has an equal right to follow any school of thought, but has no right to force the choice on any other. Neither a candidate for any office nor any voter can be rendered ineligible to stand or to vote, because of any opinion held, or because of membership in any school of thought. Opinions or beliefs neither bestow privileges nor inflict penalties. The Members of the General Council earnestly request every member of the Theosophical Society to maintain, defend and act upon these fundamental principles of the Society, and also fearlessly to exercise the right of liberty of thought and of expression thereof, within the limits of courtesy and consideration for others. Freedom of the Society The Theosophical Society, while cooperating with all other bodies whose aims and activities make such cooperation possible, is and must remain an organization entirely independent of them, not committed to any objects save its own, and intent on developing its own work on the broadest and most inclusive lines, so as to move towards its own goal as indicated in and by the pursuit of those objects and that Divine Wisdom which in the abstract is implicit in the title ‘The Theosophical Society’. -

Reminiscences of H. P. Blavatsky and "The Secret Doctrine"

REMINISCENCES OF H. P. BLAVATSKY AND "THE SECRET DOCTRINE" BY THE COUNTESS CONSTANCE W ACHTMEISTER, F. T.S . AND OTHERS EDITED BY A FELLOW OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY LONDON: THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING SOCIETY, 7, 'DuKE STREET, ADELPHI, LoNDON, W.C. N:s:w YoRK: The Path, 144, Madison Avenue. MADRAS: Theosophical Society, Adyar. 1893 (All ri-:hts reserved.) ,......--------- ----~ ----~-- •PREFACE. This book has been written by several persons who had the advantage of being the most closely connected with Madame Blavatsky during her residence in Europe, while she was engaged in the great work of her life-" The Sec·nt Doctrine." It would be a difficult task to give full, detailed accounts of all the circumstances which occurred during the preparation of this remarkable work, because it must never be forgotten that H.P.B. was, as she often herself expressed it, only the compiler of the work. Behind her stood #he real teachers, the guardians of the Secret Wisdom of the Ages, who taught her a!l the occult lore that she tr .msmitted in writing. Her. merit consisted partly in being able to assimilate the transcendental knowledge which was given out, in being a worthy messenger of her Masters, partly in her marvellous capability of rendering abstruse Eastern metaphysical thought in a form intelligible to Weste1n minds, verifying and comparing Eastern Wisdom with Western Science. Much credit, also, is due to her for her great moral courage in representing to the world thoughts and theori~s wholly at variance with the materialistic Science of the present day. It will be understood with difficulty by many, that the much abused "phenomena·· played an important pari in the compilation of" The Secret Doctrine;" that H.P.B. -

Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and Its Feminist Implications

Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications PER FAXNELD Stockholm University Abstract H. P. Blavatsky’s influential The Secret Doctrine (1888), one of the foundation texts of Theosophy, contains chapters propagating an unembarrassed Satanism. Theosophical sympathy for the Devil also extended to the name of their journal Lucifer, and discussions conducted in it. To Blavatsky, Satan is a cultural hero akin to Pro- metheus. According to her reinterpretation of the Christian myth of the Fall in Genesis 3, Satan in the shape of the serpent brings gnosis and liberates mankind. The present article situates these ideas in a wider nineteenth-century context, where some poets and socialist thinkers held similar ideas and a counter-hegemonic reading of the Fall had far-reaching feminist implications. Additionally, influences on Blavatsky from French occultism and research on Gnosticism are discussed, and the instrumental value of Satanist shock tactics is con- sidered. The article concludes that esoteric ideas cannot be viewed in isolation from politics and the world at large. Rather, they should be analyzed both as part of a religious cosmology and as having strategic polemical and didactic functions related to political debates, or, at the very least, carrying potential entailments for the latter. Keywords: Theosophy, Blavatsky, Satanism, Feminism, Socialism, Ro- manticism. In September 1875, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891) co-founded the Theosophical society in New York City. Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), lawyer and journalist, was elected its first president. Blavatsky, however, became the chief ideologist, drawing authority from the com- munications concerning esoteric matters she claimed to receive from the mysterious ‘Mahatmas’ (or ‘Masters’). -

The Eclectic Theosophist May 15

NO. 28 The Eclectic Theosophist May 15. 1975 A BI-MONTHLY NEWSLETTER FROM POINT LOMA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Subscription for one year P.O. Box 9966 — San Diego, California 92109 16 issues!, $2.50 (U.S.A.! Editors: W. Emmett Small, Helen Todd per Copy 50c "H. P. BLAVATSKY AND THE Charles James Ryan, born in Halifax, England, in 1865, THEOSOPHICAL MOVEMENT" was the son of an artist and himself an artist by profession, PUBLISHER'S PREFACE having studied under Sir Hubert von Herkomer, R.A., at his School of Painting at Bushey, near London. His specialty This impartial and challenging history by Charles J. Ryan was first was landscapes and some portraiture, and in these he was published in 1937. A second edition is particularly called for in this exhibiting in the Royal Academy in London at the age of 26. centennial year of the founding of the Theosophical Society.—Eds. But his chief interest was in Theosophy, and he became a member of the Theosophical Society in the early 1890’s, There need be no apology for a second edition of this and in the year 1900 left England and moved to the Point volume. When V.B.N. wrote in the London Sunday Referee Loma, California, Theosophical Headquarters to further the (January 7, 1934), that H. P. Blavatsky had changed “the work centered there. From then on he became best known whole current of European thought” in the nineteenth cen for his contributions to theosophical journals for over half tury, he only anticipated what forward minds of the twentieth a century on science, archaeology, art, architecture, astrono century would corroborate, and that the Great Ideas she my, and as a reviewer and critic of current scientific events sowed and so generously elucidated in philosophical expo in relation to Theosophy. -

Reminiscences of Colonel H. S. Olcott

$/->(, 7. tk /y t REMINISCENCES OF COLONEL H. S. OLCOTT BY VARIOUS WRITERS * COMPILED BY HRIDAYA NARAIN AGARWAL, M.A., LL.B. r~ THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE Adyar, Madras, India 1932 L.3t. THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY 591100 A ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS If 1932 L ACKN O WLEDGME N T MOST of these Reminiscences have been reprinted from various journals with the kind permission of the Editors. References are indicated in the table of Contents. H. S. OLCOTT an. officer in the Federal Army, in the early part of the Civil War in U.S.A. 1861—1865. -J f J i I A* I Jj PREFACE TO many the name of Colonel H. S. Olcott merely recalls the fact that he was President of the Theosophical Society, but the intrinsic value of his work is not adequately recognised. Truly, Madame H. P. Blavatsky was the teacher and the originator of Theosophy, but the credit for the propagation of the Theo- sqphical truths goes largely to Colonel Olcott. Undoubtedly, without him the mere existence of those truths was certain, but the splendid Organisation—The Theosophical Society-—is chiefly due to his great zeal and earnest endeavours. ^ To remind us, therefore, of the great part tD " played by him in the organisation of the Theosophical Society, I have ventured to w , . 1 1 compile this little book as a loving tribute to his q q , memory, on the occasion of the Founders’ Convention of the Society held at Adyar in December, 1931. Madame H. P. Blavatsky was born on August 11, 1831, and Colonel Olcott on August 2, 1832. -

The Theosophical Society's Ongoing Problem of Emotion and Control

Taming the Astral Body: The Theosophical Society’s Ongoing Problem of Emotion and Control John L. Crow Florida State University Abstract In New York City in 1875, a group interested in Spiritualism and occult science founded what would become the Theosophical Society. Primarily the creation of Henry Steel Olcott and Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the Theosophical Society went through a number of early incarnations. One original version promised to teach occult powers. After Blavatsky found that she could not honor earlier promises to teach occultism, she shifted the focus of the Society to one that promoted Universal Brotherhood instead, highlighting notions of the body and demanding the control of emotion as a means to rebuff demands for training. With this refocusing, Blavatsky reestablished control of the Society and asserted herself as the central channel of esoteric knowledge. Thus, by shifting the focus from the attainment of occult powers to the more ambiguous “spiritual enlightenment,” Blavatsky erected an elaborate, centralized system of delayed spiritual gratification, a system contingent upon the individual’s adoption of specific morals and values, while simultaneously maintaining control of the human body on all its levels: spiritual, social, physical, mental, and especially emotional. Introduction During a meeting of the Theosophical Society in New York City on October 18, 1876, the co-founder and legal counsel for the newly established organization, William Quan Judge (1851– 96), gave a lecture about his personal experiences in the study of Theosophy. He spoke about his recent experiences of astrally traveling and implanting his thoughts and ideas into the minds of others. He did this through focusing his will and commanding his “double,” or astral body, to go to these places and influence others. -

Varieties of Spiritual Individualisation in the Theosophical

Cornelia Haas Varieties of spiritual individualisation in the theosophical movement: the United Lodge of theosophists India as climax of individualisation-processes within the theosophical movement Helena Blavatsky’s ‘Theosophical Movement’, founded in 1875 in New York, shows itself in its beginnings as an example of detraditionalisation from conven- tional forms of religion. This is associated with an opening for individual and experimental approaches to new and foreign forms of religions and spiritualities. The later increase in institutionalisation within the movement provided less space for this sort of individuality and led to divisions and splits within the movement. This chapter aims to identify and extract the specific dynamics of processes of individualisation, as well as de-individualisation, within the theosophical movement in the form of a step model. The latter in the United Lodge of Theoso- phists’ (U.L.T.) ‘method’ and individual approach to Helena Blavatsky’s theoso- phy, which has as its sole focus the pursuit of the individual and its perfection. This pursuit is understood as an act of unification with the Divine or higher self, as well as with the community of likeminded persons, in a way that is both indi- vidual and vital, as well as providing a service for humanity. Certain features of this process are methods for an ultimate elimination of disturbances that obstruct the study and spread of the true teachings of Blavatsky, seen as a manifestation of divine wisdom. However, an essential component of this process is the realisation of one’s own, individual path. 1 Introduction The Theosophical Society (TS), established in 1875 in New York, introduced a per- spective on the world that its founder, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, later defined in the subtitle of her Opus magnum opus, ‘Secret Doctrine’ (1888), as a ‘Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy’. -

Modern Exact Science”

Whitney Houston Summer Olympic 1988 in Seoul/South Korea * Give me one moment in time, * When I'm more than I thought I could be, * When all of my dreams are a heart beat away, * And the answers are all up to me, * Give me one moment in time, * When I'm racing with destiny. The Secret Doctrine (according to SD 1:272 ff) Theosophy teaches there is an ancient Secret Doctrine on the mysteries of the Cosmos, Nature and Man, which is the accumulated Wisdom of the Ages, and that its mysterious symbolism is all recorded on a few pages of geometrical signs and glyphs according to an uninterrupted record of men, who had developed and perfected their physical, mental, psychic, and spiritual organizations to the utmost possible degree. That no vision of one of these adepts was accepted till it was checked and confirmed by the visions—so obtained as to stand as independent evidence —of other adepts, and by centuries of experience. The Great Master's Letter ULT Pamphlet No. 33 “The doctrine we promulgate… must become ultimately triumphant, like every other truth... enforcing its theories … with direct inference , deduced from and corroborated by the evidence furnished by “modern exact science”. Time – moves on with noiseless, incessant step through aeons and ages ... from Karmic Visions by HPB, in CW IX:325 Time is an Illusion The Secret Doctrine 1:35 Time is only an illusion produced by the succession of our states of consciousness as we travel through eternal duration, says the Secret Doctrine, and it does not exist where no consciousness exists in which the illusion can be produced, but “lies asleep.” The present is only a (hypothetical ) mathematical line which divides that part of eternal duration which we call the future , from that part which we call the past. -

Theosophy Is of the Devil by David J

Theosophy is of the Devil By David J. Stewart I could have just as easily saved this article under "New Age" or "Witchcraft," because there's not a dime's difference between the two. I saved it under "New Age" because the primary agenda of Theosophy is to further the New World Order, i.e., the Beast system of the coming Antichrist. The following historical information concerning Theosophy is a quote from Wikipedia.com... Photo to Right: Occultist and Satan worshipper, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky Theosophy, literally "god-wisdom" (Greek: θεοσοφία theosophia), designates several bodies of ideas. The 6th century neo-platonist Pseudo-Dionysius seems to have been the first philosopher the term applied to. There was a group of Renaissance philosophers: Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus, Robert Fludd, and, especially, Jacob Boehme; the Enlightenment theologian Emanuel Swedenborg was influenced by these. And finally, the word was revived in the nineteenth century by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky to designate her religious philosophy which holds that all religions are attempts by humanity to approach the absolute, and that each religion therefore has a portion of the truth. Together with Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge, and others, Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. This society has since split into a number of organizations, some of which no longer use the term "theosophy." SOURCE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theosophy Please notice that Helena Petrovna Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. Her most popular work was a two- volume book she wrote titled 'The Secret Doctrine,' in which she woefully states... "Lucifer represents.. Life. -

E-Newsletter, May,2017

INDIAN SECTION: THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, VARANASI e-Newsletter, May,2017 • Lord Buddha views of Great Teachers of Occult Hierarchy--- • “I will first say that there can be no Planetary Spirit that was not once material or what you call human. When our great Buddha — the patron of all the adepts, the reformer and the codifier of the occult system, reached first Nirvana on earth, he became a Planetary Spirit; i.e. — his spirit could at one and the same time rove the interstellar spaces in full consciousness, and continue at will on Earth in his original and individual body. For the divine Self had so completely disfranchised itself from matter that it could create at will an inner substitute for itself, and leaving it in the human form for days, weeks, sometimes years, affect in no wise by the change either the vital principle or the physical mind of its body. By the way, that is the highest form of adeptship man can hope for on our planet.” • The Great Wesak Blessing on 10.05.2017 • • Bishop Charles W. Leaderbeater a renowned theosophist and occultist writes: • • "The Lord Gautama Buddha, instead of devoting Himself wholly to other and higher work after His Mahaparanirvana, has remained sufficiently in touch with our world to be reached by the invocation of His successor when necessary, so that His advice and help can still be obtained in any great emergency. He also undertook to return to the world once in each year and shed upon it a flood of blessing. • • The Lord Buddha has His own special type of force, which He outpours when He gives His blessing to the world, and this benediction is a unique and very marvelous thing; for by His authority and position, a Buddha has access to planes of nature which are altogether beyond our reach, hence He can transmute and draw down to our level the forces peculiar to those planes. -

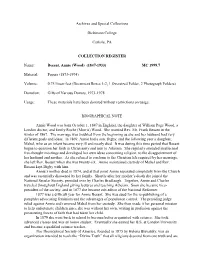

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Besant, Annie (Wood) (1847-1933) MC 1999.7 Material: Papers (1873-1974) Volume: 0.75 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-2, 1 Oversized Folder, 2 Photograph Folders) Donation: Gifts of Various Donors, 1973-1978 Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Annie Wood was born October 1, 1847 in England, the daughter of William Page Wood, a London doctor, and Emily Roche (Morris) Wood. She married Rev. Mr. Frank Besant in the winter of 1867. The marriage was troubled from the beginning as she and her husband had very different goals and ideas. In 1869, Annie had a son, Digby, and the following year a daughter, Mabel, who as an infant became very ill and nearly died. It was during this time period that Besant began to question her faith in Christianity and turn to Atheism. She regularly attended intellectual free-thought meetings and developed her own ideas concerning religion, to the disappointment of her husband and mother. As she refused to conform to the Christian life required by her marriage, she left Rev. Besant when she was twenty-six. Annie maintained custody of Mabel and Rev. Besant kept Digby with him. Annie’s mother died in 1874, and at that point Annie separated completely from the Church and was essentially disowned by her family. Shortly after her mother’s death she joined the National Secular Society, presided over by Charles Bradlaugh. Together, Annie and Charles traveled throughout England giving lectures and teaching Atheism.