Forms of Luminosity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

141715257.Pdf

2 April 30, 1996 ..::;:~:(" The Other Press is qot~Jias College's autonorno{ls itudent newspaper. We havi n Congratulations to Douglas College Presi to us. We heard nothing more from you re publishing since 19~~ fJ dent, Dr. Susan Hunter-Harvey. She has Being autonomous ~?. r garding this sensitive subject. the. Douglas Coli~ r,, · been an extremely busy woman during the Being a successful women in your field, it's Society nor the Coli · ··· ·· administration ~n 'II U_. r past school year and, in the process, has odd that you didn't jump at the chance to Press what to pnnt. p M• the managed to achieve significant success in students, can decidi' -~ gpes in encourage other women to strive for excel the paper--by helpi~g 0u · ~ the college community. However, after many lence and equality in their chosen ambitions. J 1 ®4 attempts to interview the president so that Oh well. :~d=~o~~:!~u students may get to know her better, she has The other day, we sent a reporter up to the semest$r af~istratioh, ~nd from local apd nati~nal advet1ising also managed to avoid meeting the student president's office to talk to you, much like we raven~, $ ~ \ J\A press o(Douglas College. The following is an did in the past when Bill Day was the presi L,· . ? open letter to Dr. Susan Hunter-Harvey ex dent of the college. We were always able to ~~et;;a:Tinil~':;y~:S~~ cooJ)e[ative of ~tuck,nt newspapers pressing our concern about this issue. -

Alcohol Banned After Texas-OU Annual Meeting Committee's Walks

TCU Daily Skiff Thursday, October 7, 1993 Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas 91st Year, No. 25 Alcohol banned after Texas-OU annual meeting Police cancel Commerce rally, offer Red River Round-up By R. BRIAN SASSER TCU Daily Skiff o open alco- Texas-Oklahoma weekend in Dal- "N, las may be one of college football's holic containers will be oldest traditions, but for fans plan- allowed in the Central ning on drinking alcohol on Com- Business District. There merce Street, this year is a whole new is no more Commerce game. Street rally." This year, the law against public consumption of alcohol will be enforced, said Ed Spencer, ED SPENCER, spokesman for the Dallas Police Dallas Police Department Department. spokesman "No open alcoholic containers will be allowed in the Central Business certs and other activities that will be District." Spencer said. "There is no gated and ticketed, according to a more Commerce Street rally." Round-up fact sheet. A homicide and several assaults A schedule of Round-up events during last year's Texas-OU week- will appear in a special section of The end convinced the city and the police Dallas Morning Sews on Oct. 8. the TCU Dally Skiff/ Aimee Herring something must be done to insure fact sheet said. The TCU Symphony Orchestra practices in Ed Landreth Hall Auditorium on Tuesday for Wednesday's concert. public safety. Spencer said. Downtown Dallas businesses are "Officers will be courteous, but very receptive to the new tradition fair," he said. "However, if arrests are necessary, arrests will be made." and activities. -

Contwe're ACT

Media contacts for Linkin Park: Dvora Vener Englefield / Michael Moses / Luke Burland (310) 248-6161 / (310) 248-6171 / (615) 214-1490 [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] LINKIN PARK ADDS BUSTA RHYMES TO 2008 SUMMER TOUR ACCLAIMED HIP HOP INNOVATOR WILL PERFORM WITH LINKIN PARK, CHRIS CORNELL, THE BRAVERY, ASHES DIVIDE ON PROJEKT REVOLUTION MAIN STAGE REVOLUTION STAGE HEADLINED BY ATREYU AND FEATURING 10 YEARS, HAWTHORNE HEIGHTS, ARMOR FOR SLEEP & STREET DRUM CORPS TOUR BEGINS JULY 16 IN BOSTON Los Angeles, CA (June 3, 2008) – Multi-platinum two-time Grammy-winning rock band Linkin Park has announced that acclaimed hip-hop innovator Busta Rhymes will join their Projekt Revolution 2008 lineup. Rhymes and Linkin Park recently collaborated on “We Made It,” the first single and video from Rhymes’ upcoming album, Blessed. By touring together, Linkin Park & Busta are taking a cue from the chorus of their song: “…we took it on the road…”. As recently pointed out in Rolling Stone’s “Summer Tour Guide,” the tour will see nine acts joining rock superstars Linkin Park, who are also offering concertgoers a digital souvenir pack that includes a recording of the band’s entire set. As the band’s co-lead vocalist Mike Shinoda told the magazine, “That puts extra pressure on us to make sure our set is different every night.” The fifth installation of Linkin Park’s raging road show will see them headlining an all-star bill that features former Soundgarden/Audioslave frontman Chris Cornell, electro-rockers The Bravery and Ashes Divide featuring Billy Howerdel, known for his work with A Perfect Circle. -

Columbia Chronicle (02/21/1994) Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 2-21-1994 Columbia Chronicle (02/21/1994) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (02/21/1994)" (February 21, 1994). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/191 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. exclusive Page9 THE CDLUMBIA COLLEGE !VOLUME 27 NUMBER 14 FEBRUARY 21, 1994j By Joseph Schrank Nn.~~Uilo> Clips, clips, and more clips! That was the leading bit of advice from Chicago'sjoumalism experts to aspiring Columbia College minority journalists trying to break into the business. Mae than 200 Columbia students met professionals during Cohunbia. s 4th Annual Minority Joumalism Job Fair, held Feb. S in the Holrin Annex c:L the Wallash building. The event, co-sponsored by the Clttcato H•adllne Club and Columbia's Career Pkmnlnt and Plllc•ment Of/lei, offered stu dents advice and workshops, networking and mentoring. Lee Bey, Chicago Sun-Times reporter on left shares lnf'orrna1~on The morning part of the program about job opportunities with Kwane Burton, at the Journalism Job consisted of a panel discussion by Fair held at Hokln Hall. -

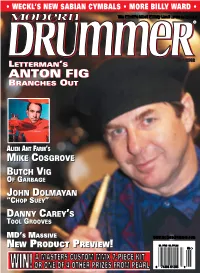

June 2002 BBRANCHESRANCHES OOUTUT

• WECKL’S NEW SABIAN CYMBALS • MORE BILLY WARD • LLETTERMANETTERMAN’’SS ANTANTONON FIGFIG June 2002 BBRANCHESRANCHES OOUTUT AALIENLIEN AANTNT FFARMARM’’SS MMIKEIKE CCOSGROVEOSGROVE BBUTCHUTCH VVIGIG OOFF GGARBAGEARBAGE JJOHNOHN DDOLMAOLMAYYANAN “C“CHOPHOP SSUEYUEY”” DDANNYANNY CCAREYAREY’’SS TTOOLOOL GGROOVESROOVES MD’MD’SS MMASSIVEASSIVE NEW PRODUCT PREVIEW! $4.99US $6.99CAN NEW PRODUCT PREVIEW! 06 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 26, Number 6 David Letterman’s ANTON FIG Obscure South African drummer becomes first-call drummer for New York’s most prestigious gigs. Read all about it. by Robyn Flans 38 Paul La Raia Alien Ant Farm’s UPDATE 20 MIKE COSGROVE Sveti’s Marko Djordjevic The AAF formula for heavy-rock success? Ghetto beats, a Michael 52 CPR’s Stevie Di Stanislao Jackson cover, and work, work, Willie Nelson’s Paul & Billy English Alex Solca and more work. by David John Farinella Japanese Tabla Synthesist Asa-Chang Warrant’s Mike Fasano Garbage’s Lamb Of God’s Chris Adler BUTCH VIG That rare artist with platinum experi- ROM HE AST ence on both sides of the glass, 62 F T P 132 Butch Vig knows of what he speaks. WEST COAST BEBOP PIONEER Alex Solca by Adam Budofsky ROY PORTER He carried first-hand knowledge from Charlie Parker to the West Coast, and helped MD’S PRODUCT EXTRAVAGANZA usher in a new chapter in jazz history. by Burt Korall Gearheads of the world, this is your issue! WOODSHED 138 76 CHRIS VRENNA Running on caffeine and plenty of ROM, ex–Nine Inch Nails drummer Chris Vrenna creates sonic scenarios unlike anything you’ve heard. -

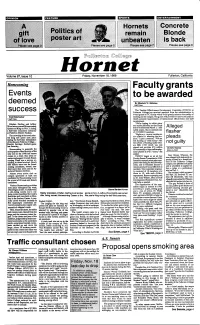

The Hornet, 1923 - 2006 - Link Page Previous Volume 67, Issue 10 Next Volume 67, Issue 12

ON 0 A Hornets Concrete gift Politics of remain Blonde of love poster art unbeaten is back Please see page 3 Please see page 5 Please see page 7 Please see page 6 .6oum Isu0tuoen n toCo Volume 67, Issue 10 Friday, November 18, 1988 Fullerton California Homecoming S'. .. .. Faculty grants Events to be awarded deemed By Elizabeth W. Hickman success Staff Writer The Teacher Effectiveness Development Committee (TEDCO) at Fullerton College has received approval from the administration to award grants to FC faculty which could greatly enhance the quality of Todd Rohrbacher teaching on the campus. The grants will provide for innovative projects Staff Writer which promote improvement of instructional effectiveness and staff development. Kristian Darling and Jeffrey "We're hoping to solicit plans were crowned Homecoming and make decisions so that funds Alleged Wood allocated March 1," said Queen and King on Nov. 5, during are to be a half-time coronation ceremony Adela Lopez, who is currently one f he r at Fullerton District Stadium. of 15 TEDCO members. "Right now, we are working on The crowning of the newly elec- p the criteria fo selecting the pro- p le ad S ted king arid queen took place jecis," Lopez continued. "We see during the half-time intermission this funding as 'seed money' with not of the climactic Fullerton College- the advent of funding under (Sen- gu It Rancho Santiago football -game ate Bill) 1725 which was just last Saturdays:. signed and provides $70 million By Eric Marson Homecoming' is generally the for community college staffdevelop- Editor-in-Chief most popular school activity of the ment phased in over 3 years," she year and as the 1988 fall season added. -

1993 Highlander Vol 75 No 6 November 11, 1993

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Archives and Special Collections Newspaper 11-11-1993 1993 Highlander Vol 75 No 6 November 11, 1993 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1993 Highlander Vol 75 No 6 November 11, 1993" (1993). Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper. 36. https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander/36 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University I , HIGHLANDER Vol. 75 No.6 Denver, Colorado November 11, 1993 Slain Scholar Never Played By Rules by Diana Smith the first white American to die in She went into a lot of things Special Correspondent the violence that has claimed more with self-confidence and com College Press Service than 15,000 blacks since the mid- mitment," said McFaul, a re 1980s, according to wire reports. search associate at the Center By all accounts, Amy Biehl Since then, colleagues, friends for International Security and was dedicated, enthusiastic and and family have been trying to Arms Control at Stanford . fearless in hernearly year-long make some sense of her death. In McFaul helped supervise effort to help blacks get their · early September, her parents, peter Biehl' s senior thesis and they fair share of political power in and Linda Biehl of Newport Beach, later became friends when she South Africa. -

The Concrete Blonde Free Download

THE CONCRETE BLONDE FREE DOWNLOAD Michael Connelly | 448 pages | 06 Nov 2014 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781409156161 | English | London, United Kingdom Recent Posts Tribute albums were also starting to really become a bigger thing, so I thought there might be enough artists interested in doing one dedicated to The Carpenters. Robert Smith in the Cure's "Lullaby". God Is a Bullet. During the trial, the police receive a note, purportedly from the Dollmaker, which leads to the discovery of a new victim killed by someone using the same modus operandi. Jazz Latin New Age. All Rights Reserved. The The Concrete Blonde of a love affair torn apart by alcoholism serves as the theme for Concrete Blonde's heart-wrenching "Joey. All of them? Others found a contrasting middle ground between the slick pop craftsmanship of the originals and their own sonic predilections. In Decemberthe band engaged in a small tour of nine cities, mostly on the east coast of the U. Little The Concrete Blonde. See all 47 reviews. Pricing policy About our prices. He was The Concrete Blonde monster. See more. Roses Grow [Live]. I think Richard felt appreciated. Just as the trial begins, a new murder victim is discovered and there appear to be links to the murders committed by the Doll Maker. Jenny Lewis On Loving L. They were really close to me, no pun intended. For their debut album, see Concrete Blonde album. Australian Chart Book — Rainy Day Relaxation Road Trip. He wants attention. But there is still much The Concrete Blonde to be interpreted by the song, and the video. -

The Road Tales from Touring Musicians

THE ROAD TALES FROM TOURING MUSICIANS TONY PATINO COVER ART BY JOSHUA ROTHROCK Copyright © 2012 Tony Patino No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the the author. ISBN-13: 978-1475132649 ISBN-10: 1475132646 second edition paperback June 2012 Editor: Tony Patino Cover art: Joshua Rothrock Cover and interior layout: Tony Patino www.tonypatinosworld.com www.40amp.com [email protected] CONTENTS FORWARD MOJO NIXON solo artist 1 JOHN STANIER helmet, battles 4 TEXAS TERRI texas terri bomb 6 CHRIS GATES the big boys, junkyard 7 BRANDON CRUZ dead kennedys, dr. know 10 WILLIAM WEBER gg allin, the candy snatchers 12 GERRY ATTRIC the bulemics 15 WES TEXAS the bulemics 16 ANIMAL the anti-nowhere league 18 TIM BARRY avail 19 NICKI SICKI verbal abuse 22 RICHIE LAWLER clairmel 24 DAVE DECKER clairmel 26 JOHN KASTNER asexuals, the doughboys 29 SCOTT MCCULLOUGH the doughboys 32 BLAG DAHLIA the dwarves 34 KARL MORRIS the exploited, billyclub 38 JIM COLEMAN cop shoot cop 41 STONEY TOMBS the hookers 42 MIKE WATT the minutemen 43 CHRIS BARROWS pink lincolns 44 TESCO VEE the meatmen 46 NATE WATERS infected 49 TIM LEITCH fear 52 IAN MACKAYE minor threat, fugazi 53 DONNY PAYCHECK zeke 55 GINGER COYOTE white trash debutantes 57 BEN DEILY the lemonheads 58 SAM WILLIAMS down by law 61 FARRELL HOLTZ decry 63 TONY OFFENDER the offenders 65 SAMMYTOWN fang 66 JAMES BROGAN samiam -

Ladyslipper Catalog Table of Contents

I ____. Ladyslipper Catalog Table of Contents Free Gifts 2 Country The New Spring Crop: New Titles 3 Alternative Rock 5g Celtic * British Isles 12 Rock * Pop 6i Women's Spirituality * New Age 16 R&B * Rap * Dance 64 Recovery 27 Gospel 64 Native American 28 Blues ' 04 Drumming * Percussion 30 Jazz • '. 65 African-American * African-Canadian 31 Classical 67 Women's Music * Feminist Music 33 Spoken .... 68 Comedy 43 Babyslipper Catalog 70 Jewish 44 Mehn's Music 72 Latin American 45 Videos 75 Reggae * Caribbean 47 Songbooks * Sheet Music 80 European 47 Books 81 Arabic * Middle Eastern 49 Jewelry, Cards, T-Shirts, Grab-Bags, Posters 82 African 49 Ordering Information 84 Asian * Pacific 50 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 51 Artist Index 86 Free Gifts We appreciate your support, and would like to say thank you by offering free bonus items with your order! (This offer is for Retail Customers only.) FMNKK ARMSTRONG AWmeuusic PIAYS SO GHMO Order 5 items: Get one Surprise Recording free! Our choice of title and format; order item #FR1000. Order 10 items: choose any 2 of the following free! Order 15 items: choose any 3 of the following free! Order 20 items: choose any 4 of the following free! Order 25 items: choose any 5 of the following free! Order 30 items: choose any 6 of the following free! Please use stock numbers below. #FR1000: Surprise Recording - From Our Grab Bag (our choice) #FR1100: blackgirls: Happy (cassette - p. 52) Credits #FR1300: Frankie Armstrong: ..Music Plays So Grand (cassette - p. 14) #FR1500: Heather Bishop: A Taste of the Blues (LP - p. -

Chanticleer | Vol 41, Issue 15

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 1994-01-13 Chanticleer | Vol 41, Issue 15 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | Vol 41, Issue 15" (1994). Chanticleer. 1108. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1108 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 Thursday, January 13,1994 and parents about criminal activ- have been perfectly legal," Griggs occurred in February when a fe- Jennifer Burgess ity on campus. College Press Service added. male student was arrested and Bringing a gun onto a college The university reported 10 ar- charged with possession of a .22- Students at campuses nation- campis, even if it is properly reg- rests for weapons in 1991, Griggs caliber revolver on campus. The wide are packing more than books istered, is a third-degree felony said. arrest was made after a shot was in their backpacks. A recent sur- under federal law. -- Lt. Brad Wigtil, with the Uni- fired through a male student's vey shows many students are car- At the University ofTexas-Aus- versity of Houston police depart- windshield during an argument, rying handguns onto campus. tin, freshman David Matthew ment, said the guns on the Wigtil said. According to a survey published Larsen was arrested after police univeristy's campus can also be The three other guns were found on Jan. -

College Voice Vol. 17 No. 3

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 1993-1994 Student Newspapers 9-21-1993 College Voice Vol. 17 No. 3 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_1993_1994 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 17 No. 3" (1993). 1993-1994. 18. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_1993_1994/18 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1993-1994 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE COL EVOICE Volume:xvrr. Number 3 Ad Fontes September 21. 1993 Gender-neutral language under fire Psycholo~JY class requiremement prompts questions about political correctness by Heather Ennln man kind" (rather than the generic mote accuracy as well as the fair thors who are submitting their recommend that students use what- The College Voice and supposedly inclusive "man- treatment of people and groups," manuscripts to an APA jourual to ever system they want. Just be • nd kind," ..man," ..men, .. as in "Man is said Martin . use nonsexist language, that is, to consistent. Male writers use he and Brett Goldstl,~n a rational animal") Martin continued by explaining avoid in their manuscripts language female writers use she. It's exces- Acting Associate Ne~.s Editor Use "men" and "women" when the essence of being fair and that could be construed as sexist." sively politically correct to demand Politically correct terminology you mean it in the exclusive gender empathetic in language.