VISUAL STORYTELLING the Digital Video Documentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Videography and Photography: Critical Thinking, Ethics and Knowledge-Based Practice in Visual Media

Videography and photography: Critical thinking, ethics and knowledge-based practice in visual media Storytelling through videography and photography can form the basis for journalism that is both consequential and high impact. Powerful images can shape public opinion and indeed change the world, but with such power comes substantial ethical and intellectual responsibility. The training that prepares journalists to do this work, therefore, must meaningfully integrate deep analytical materials and demand rigorous critical thinking. Students must not only have proficient technical skills but also must know their subject matter deeply and understand the deeper implications of their journalistic choices in selecting materials. This course gives aspiring visual journalists the opportunity to hone critical-thinking skills and devise strategies for addressing multimedia reporting’s ethical concerns on a professional level. It instills values grounded in the best practices of traditional journalism while embracing the latest technologies, all through knowledge-based, hands-on instruction. Learning objectives This course introduces the principles of critical thinking and ethical awareness in nonfiction visual storytelling. Students who take this course will: Learn the duties and rights of journalists in the digital age. Better understand the impact of images and sound on meaning. Develop a professional process for handling multimedia reporting’s ethical challenges. Generate and translate ideas into ethically sound multimedia projects. Understand how to combine responsible journalism with entertaining and artistic storytelling. Think and act as multimedia journalists, producing accurate and balanced stories — even ones that take a point of view. Course design This syllabus is built around the concept of groups of students going through the complete process of producing a multimedia story and writing journal entries about ethical concerns that surface during its development and execution. -

Resingularizations of the Avant Garde in East Austin, Texas a Dissertation

East of the Center: Resingularizations of the Avant Garde in East Austin, Texas A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Carra Elizabeth Martinez IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Sonja Kuftinec, Advisor May 2016 Copyright Carra Elizabeth Martinez May 2016 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of the Department of Theatre Arts and Dance at the University of Minnesota. My committee generously provided their time and attention and feedback: Dr. Sonja Kuftinec, Dr. Michal Kobialka, Dr. Margaret Werry, Dr. Cindy Garcia, and Dr. Josephine Lee. My fellow graduate students filled my days at the U of M with laughter, conversation, and potlucks. Thank you Elliot Leffler, Jesse Dorst, Kimi Johnson, Eric Colleary, Stephanie Walseth, Will Daddario, Joanne Zerdy, Rita Kompelmacher, Mike Mellas, Bryan Schmidt, Kelly McKay, Kristen Stoeckeler, Hyo Jeong Hong, Misha Hadar, Rye Gentleman, David Melendez, Virgil Slade, Wesley Lummus, and Cole Bylander. Both Barbra Berlovitz and Lisa Channer provided so many pathways for me to stay in touch with the creative process inside Rarig. I will now always want to play both Agamenon and Clytemnestra in the same production. My fellowship at Penumbra Theatre kept me attune to the connection between practice and theory. And last but not least, thank you to my University of Minnesota Theatre Arts and Dance students, who were so willing to take risks and to work and to think. A special thanks goes to the Bootleggers. I always smile when I drive by any and all Halloween stores. -

Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2017 yS mposium Apr 12th, 3:00 PM - 3:30 PM Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M. DePree Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons DePree, Kelsey M., "Cue the Music: Music in Movies" (2017). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2017/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Music We Watch Kelsey De Pree Music History II April 5, 2017 Music is universal. It is present from the beginning of history appearing in all cultures, nations, economic classes, and styles. Music in America is heard on radios, in cars, on phones, and in stores. Television commercials feature jingles so viewers can remember the products; radio ads sing phone numbers so that listeners can recall them. In schools, students sing songs to learn subjects like math, history, and English, and also to learn about general knowledge like the days of the week, months of the year, and presidents of the United States. With the amount of music that is available, it is not surprising that music has also made its way into movie theatres and has become one of the primary agents for conveying emotion and plot during a cinematic production. -

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in Its Place

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in its Place. Professor Stephen Deutsch The Soundtrack Vol 1, No 1, 2008 tbc Intellect Press http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals.php?issn=17514193 Abstract There are currently many books and journals on film music in print, most of which describe music as a separate activity from film, applied to images most often at the very end of the production process by composers normally resident outside the filmic world. This article endeavours to modify this practice by placing music within the larger notion of “the soundtrack”. This new model assumes that irrespective of industrial determinants, the soundtrack is perceived by an audience as such a unity; that music, dialogue, effects and atmospheres are heard as interdependent layers in the sonification of the film. We often can identify the individual sonic elements when they appear, but we are more aware of the blending they produce when sounding together, much as we are when we hear an orchestra. To begin, one can posit a definition of the word ‘soundtrack’. For the purposes of this discussion, a soundtrack is intentional sound which accompanies moving images in narrative film1. This intentionality does not exclude sounds which are captured accidentally (such as the ambient noise most often associated with documentary footage); rather it suggests that any such sounds, however recorded, are deliberately presented with images by film-makers.2 All elements of the soundtrack operate on the viewer in complex ways, both emotionally and cognitively. Recognition of this potential to alter a viewer’s reading of a film might encourage directors to become more mindful of a soundtrack’s content, especially of its musical elements, which, as we shall see below, are likely to affect the emotional environment through which the viewer experiences film. -

By Patricia Holloway and Carol Mahan

by Patricia Holloway and Carol Mahan ids and nature seem like a natural survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, combination, but what was natu- today’s 8- to 18-year-olds spend an average ral a generation ago is different of seven hours and 38 minutes per day on today. Children are spending entertainment media such as TV, video Kless time outdoors but continue to need games, computers, and cell phones, nature for their physical, emotional, leaving little time for nature explora- and mental development. This fact has tion or much else (2010). led author Richard Louv to suggest According to Louv, children need that today’s children are suffering nature for learning and creativity from “nature-deficit disorder” (2008). (2008). A hands-on experiential Nature-deficit disorder is not a med- approach, such as nature explo- ical term, but rather a term coined ration, can have other benefits by Louv to describe the current for students, such as increased disconnect from nature. motivation and enjoyment of While there may be many learning and improved reasons today’s children are skills, including communi- not connected with nature, cation skills (Haury and a major contributor is time Rillero 1994). spent on indoor activities. According to a national Summer 2012 23 ENHANCE NATURE EXPLORATION WITH TECHNOLOGY Digital storytelling Engaging with nature Our idea was to use technology as a tool to provide or Students need to have experiences in nature in order enhance students’ connection with nature. Students to develop their stories. To spark students’ creativ- are already engaged with technology; we wanted to ity, have them read or listen to stories about nature. -

To Film Sound Maps: the Evolution of Live Tone’S Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-Ho

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham From ‘Screenwriting for Sound’ to Film Sound Maps: The Evolution of Live Tone’s Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-ho Nikki J. Y. Lee and Julian Stringer Abstract: In his article ‘Screenwriting for Sound’, Randy Thom makes a persuasive case that sound designers should be involved in film production ‘as early as the screenplay…early participation of sound can make a big difference’. Drawing on a critically neglected yet internationally significant example of a creative alliance between a director and post- production team, this article demonstrates that early participation happens in innovative ways in today’s globally competitive South Korean film industry. This key argument is presented through close analysis of the ongoing collaboration between Live Tone - the leading audio postproduction studio in South Korea – and internationally acclaimed director Bong Joon-ho, who has worked with the company on all six of his feature films to date. Their creative alliance has recently ventured into new and ambitious territory as audio studio and director have risen to the challenge of designing the sound for the two biggest films in Korean movie history, Snowpiercer and Okja. Both of these large-scale multi-language movies were planned at the screenplay stage via coordinated use of Live Tone’s singular development of ‘film sound maps’. It is this close and efficient interaction between audio company and client that has helped Bong and Live Tone bring to maturity their plans for the two films’ highly challenging soundscapes. -

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

Filming from Home Best Practices

Instructions for Filming From Home As we continue to adapt to the current public health situation, video can be a fantastic tool for staying connected and engaging with your community. These basic guidelines will help you film compelling, high-quality videos of yourself from your home using tools you already have on hand. For more information, contact Jake Rosati in the Communications, Marketing, and Public Affairs department at [email protected]. SETTING YOUR SCENE Whether you’re using a video camera, smartphone, or laptop, there are a few simple steps you can take to make sure you’re capturing clean, clear footage. You can also use these scene-setting tips to help light and frame Zoom video calls. Background ● Make sure your subject—you, in this case—is the main focus of the frame. Avoid backgrounds that are overly busy or include a lot of extraneous motion. Whenever possible, ensure that other people’s faces are not in view. ● If you’re filming in front of a flat wall, sit far enough away to avoid casting shadows behind you. ● If you have space, you can add depth to your shot by sitting or standing in front of corners. This will draw the viewer’s eye to your subject. DO add depth to your shot by filming in front of a DON’T sit too close to a flat wall; it can cast corner. distracting shadows. Lighting ● The best at-home lighting is daylight. Try to position yourself facing a window (or set up a light if daylight isn’t an option) with your face pointing about three-quarters of the way toward the light. -

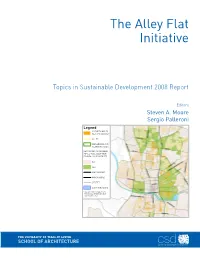

Afi-Soa-2008-Report

The Alley Flat Initiative Topics in Sustainable Development 2008 Report Editors Steven A. Moore Sergio Palleroni Legend LOT WITH ALLEY FLAT POTENTIAL* ALLEY NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING AREA SECONDARY APARTMENT INFILL TOOL ADOPTION (BY NPA / SUBDISTRICT) NO YES MAJOR ROAD MINOR ROAD STREET LADY BIRD LAKE * ALL LOTS WITH ALLEY FLAT POTENTIAL SHOWN ON MAP ARE ZONED SF-3. csd Center for Sustainable Development i THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS CENTER FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 1 UNIVERSITY STATION B7500; AUSTIN, TX DR. ELIZABETH MUELLER, DIRECTOR WORKING PAPER SERIES JULY 2008 ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PREFACE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALLEY FLATS IN FOUR CITIES 2. CONDITIONS IN AUSTIN: LANDSCAPE OF OPPORTUNITY (ELIZABETH) 2.1 REVIEW OF LOTS WITH ALLEY FLAT POTENTIAL 2.2 REVIEW OF LOTS WITH POTENTIAL FOR SECONDARY UNITS IN GENERAL 2.3 BEGINNING WITH EAST AUSTIN BECAUSE… 3. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AUSTIN’S ALLEY FLAT INITIATIVE 4. NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT 4.1 THREE CASES OF AUSTIN NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT 4.2 REGULATION 5. OWNERSHIP AND FINANCING STRUCTURES 5.1 OWNERSHIP STRUCTURES AND THEIR SUITABILITY 5.2 FUNDING SOURCES AND THEIR SUITABILITY 6. DISTRIBUTED INFRASTRUCTURE 6.1 WATER 6.2 ELECTRICITY 6.3 TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS APPENDICES A. GIS METHODS B. LIST OF KEY STAKEHOLDERS AND PARTNERSHIPS C. OWNERSHIP AND FINANCING STRUCTURES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was initially supported by a generous research grant from the Henry Luce Foundation and has subsequently been supported by the Austin Community Foundation, Perry Lorenz, and anonymous donors. Support for construction of the initial prototype has been received from Autodesk, Lincoln Properties, Wells Fargo Bank, Walter Elcock Family, HG TV, Suzi Sosa, Bercy‐Chen, Alexa Werner, Michael Casias, Meridian Energy, DXS‐Daikin, Z‐Works, Ecocreto, and Pat Flanary. -

Unprocessed Materials

BID# 09ITB12346B-BR UNPROCESSED MATERIALS Vision People Families Neighborhoods Mission To serve, protect and govern in concert with local municipalities Values People Customer Services Ethics Resource Management Innovation Equal Opportunity REQUEST FOR INVITATION TO BID NO. 09ITB12346B-BR UNPROCESSED MATERIALS For THE LIBRARY DEPARTMENT BID DUE DATE AND TIME: December 30, 2008, 11:00 A.M. BID ISSUANCE DATE: November 21, 2008 PURCHASING CONTACT: Brian Richmond at 404-612-7915 E-MAIL: [email protected] All bids must be mailed to: LOCATION: FULTON COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PURCHASING & CONTRACT COMPLIANCE 130 PEACHTREE STREET, S.W., SUITE 1168 ATLANTA, GA 30303 1 BID# 09ITB12346B-BR UNPROCESSED MATERIALS COMPANY NAME: ___________________________________________ ADDRESS: ___________________________________________ CITY: ________________________ STATE: ________________________ ZIP CODE: ________________________ CONTACT PERSON: ________________________ TELEPHONE NUMBER: ________________________ FAX NUMBER: ________________________ EMAIL ADDRESS: ________________________ Note: All vendors submitting a bid must complete this page. If you are submitting a bid, please submit the original and five copies. Vendors have up to 2:00 P.M. Monday, December 15, 2008 to email any questions that you may have. All bids should be sealed and mailed to the following address: The Fulton County Department of Purchasing and Contract Compliance 130 Peachtree Street S.W. Suite 1168 Atlanta Georgia 30303 Attn: Brian Richmond 2 BID# 09ITB12346B-BR UNPROCESSED -

Dp Harvey Milk

1 Focus Features présente en association avec Axon Films Une production Groundswell/Jinks/Cohen Company un film de GUS VAN SANT SEAN PENN HARVEY MILK EMILE HIRSCH JOSH BROLIN DIEGO LUNA et JAMES FRANCO Durée : 2h07 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 4 MARS 2008 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.snd-films.com DISTRIBUTION : RELATIONS PRESSE : SND JEAN-PIERRE VINCENT 89, avenue Charles-de-Gaulle SOPHIE SALEYRON 92575 Neuilly-sur-Seine Cedex 12, rue Paul Baudry Tél. : 01 41 92 79 39/41/42 75008 Paris Fax : 01 41 92 79 07 Tél. : 01 42 25 23 80 3 SYNOPSIS Le film retrace les huit dernières années de la vie d’Harvey Milk (SEAN PENN). Dans les années 1970 il fut le premier homme politique américain ouvertement gay à être élu à des fonctions officielles, à San Francisco en Californie. Son combat pour la tolérance et l’intégration des communautés homosexuelles lui coûta la vie. Son action a changé les mentalités, et son engagement a changé l’histoire. 5 CHRONOLOGIE 1930, 22 mai. Naissance d’Harvey Bernard Milk à Woodmere, dans l’Etat de New York. 1946 Milk entre dans l’équipe de football junior de Bay Shore High School, dans l’Etat de New York. 1947 Milk sort diplômé de Bay Shore High School. 1951 Milk obtient son diplôme de mathématiques de la State University (SUNY) d’Albany et entre dans l’U.S. Navy. 1955 Milk quitte la Navy avec les honneurs et devient professeur dans un lycée. 1963 Milk entame une nouvelle carrière au sein d’une firme d’investissements de Wall Street, Bache & Co. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e.