Why the Name of Batman Should Not Be Retained for the Federal Electorate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

Engaging Indigenous Communities

Engaging Indigenous Communities REGIONAL INDIGENOUS FACILITATOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S GOALS AND The Port Phillip & Westernport CMA employs a Regional ASPIRATIONS Indigenous Facilitator funded through the Australian During 2014/15, a study was undertaken with Government’s National Landcare Programme. In Wurundjeri, Wathaurung, Wathaurong and Boon 2014/15, the facilitator arranged numerous events Wurrung people regarding their communities’ goals and and activities to improve the Indigenous cultural aspirations for involvement in land management and awareness and understanding of Board members and sustainable agriculture. The study improved the mutual staff from the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and from understanding of priority activities for the future and various other organisations and community groups. set a basis for potential formal agreements between The facilitator also worked directly with Indigenous the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and the Indigenous organisations and communities to document their goals organisations. relating to natural resource management and agriculture. A coordinated program of grants was established to help INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT GRANTS Indigenous organisations undertake on-ground projects and training to increase employment opportunities. In 2014/15, $75,000 of Indigenous environment grants were awarded as part of the Port Phillip & Westernport IMPROVING CULTURAL AWARENESS AND CMA’s project. This included grants to: UNDERSTANDING • Wathaurung Aboriginal Corporation to run 4 community, business and corporate -

1 Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I Had the Great Honour of Carrying the Torch

1 PEOPLE WHO CHANGED MELBOURNE Schools City Tour of Melbourne: www.melbournewalks.com.au/city-schools-tour ; www.melbournewalks.com; [email protected] ; Copyright Melbourne Walks © Peter Lalor, Rebel (1827-1889) As Eureka stockade leader in December 1854 I took the oath of the rebel miners: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other to defend our rights and liberties’. I lost my arm in that battle yet later became the only outlaw ever elected to parliament! On 24 Nov 1857 all men received the right to vote. Our Southern Cross flag is now the Australian flag. Down with tyranny! John Batman, Founder of Colonial Melbourne (1801 –1839) I was a Tasmania sheep farmer when I led an expedition to sign a ‘treaty’ with Aboriginal ‘chiefs’ in 1835 to found the settlement of Melbourne and the colony of Victoria. I captured bushranger Mathew Brady and married a runaway convict Eliza Callaghan. We had seven children in all. At Melbourne’s first land sale in 1837. I bought the Young and Jackson Hotel site opposite Flinders Street Station to build a home for my children. It became a schoolhouse in 1839 and today a famous pub. See Chloe upstairs! Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I had the great honour of carrying the torch into the stadium in the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956. I was also the first man to run three miles in under 13 minutes. They said I was fastest man on the planet when I broke 17 world records and 25 Australian records in 1965. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Annual Report 2020 Facts and Trends 2019/20 2

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 FACTS AND TRENDS 2019/20 2 Import Coal Market at a Glance 2017 2018 2019 World Hard Coal Production Mill. t 6,852 7,064 7,257 World Hard Coal Trade Mill. t 1,267 1,324 1,336 of which seaborne hard coal trade Mill. t 1,157 1,208 1,221 of which internal hard coal trade Mill. t 110 116 115 Hard Coal Coke Production Mill. t 633 646 682 Hard Coal Coke World Trade Mill. t 26 28 26 European Union (28) Hard Coal Production Mill. TCE 81 76 67 Hard Coal Imports (incl. internal trade) Mill. t 172 166 134 Hard Coal Coke Imports Mill. t 9.1 9.0 9.5 Germany Hard Coal Use Mill. TCE 50.0 48.7 38.7 Hard Coal Volume Mill. TCE 51.6 47.1 37.9 of which import coal use Mill. TCE 47.9 44.4 37.9 of which domestic hard coal production Mill. TCE 3.7 2.7 0.0 Imports of Hard Coal and Hard Coal Coke Mill. t 51.4 47.0 42.2 of which steam coal 1) Mill. t 36.3 32.5 29.2 of which coking coal Mill. t 12.9 12.4 11.2 of which hard coal coke Mill. t 2.3 2.1 1.9 Prices Steam Coal Marker Price CIF NWE US$/TCE 98 108 72 Border-crossing Price Steam Coal €/TCE 92 95 79 CO2 emission rights (EEX EUA settlement price) EUR/EUA 5.83 15.82 24.84 Exchange rate (US$1 = €....) EUR/US$ 0.89 0.85 0.90 1) Including anthracite and briquettes Quelle: ??? 3 AN INTRODUCTORY WORD In 2020, it will be decided to end coal-fired power generation. -

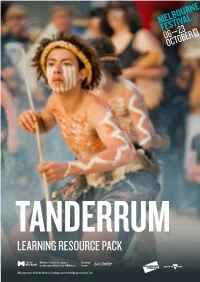

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th -

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835 By Glen Foster An historical game using role-play and cards for 4 players from upper Primary school to adults. © Glen Foster, 2019 1 Published by Port Fairy Historical Society 30 Gipps Street, Port Fairy. 3284. Telephone: (03) 5568 2263 Email: [email protected] Postal address: Port Fairy Historical Society P.O. Box 152, Port Fairy, Victoria, 3284 Australia Copyright © Glen Foster, 2019 Reproduction and communication for educational and private purposes Educational institutions downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own educational purposes. The general public downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own private use. Requests and enquiries for further authorisation should be addressed to Glen Foster: email: [email protected]. Disclaimers These materials are intended for education and training and private use only. The author and Port Fairy Historical Society accept no responsibility or liability for any incomplete or inaccurate information presented within these materials within the poetic license used by the author. Neither the author nor Port Fairy Historical Society accept liability or responsibility for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered as a result of direct or indirect use or application of this material. Print on front page shows members of the Kulin Nations negotiating a “treaty” with John Batman in 1835. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia. George Rossi Ashton, artist. © Glen Foster, 2019 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

31. John Batman's Title Deeds Author(S): George Warner and J

31. John Batman's Title Deeds Author(s): George Warner and J. Edge-Partington Source: Man, Vol. 15 (1915), pp. 49-51 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2787879 Accessed: 24-06-2016 17:04 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Fri, 24 Jun 2016 17:04:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 1915.] MAN. [No. 31. ORIGINAL ARTICLES. With Plates D and E. Australia: Victoria. Warner-Edge-Partington. John Batman's Title Deeds. By Sir George Warner and J. Edge- 2 Partinglon. UI John Batman was born at Parramatta, Sydney, in 1800, and emigrated to Van Diemen's Land twenty years later, where be became a flourishing farmer. At this time considerable difficulty was beinag experienced with the natives, and the niame of John Batman stands out as a splendid example of humane treatment, in place of the "crow-shooting" adopted by many of the settlers and ex-convicts at that time.