CHGO HIST Summer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago's Neighborhoods

Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago’s Neighborhoods Explore the cultural richness of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods through Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago’s Neighborhoods in this weekly challenge! Each week explore the history of Chicago’s neighborhoods and the challenges migrants, immigrants, and refugees faced in the city of Chicago. Explore the choices these communities made and the changes they made to the city. Each challenge comes with a short article on the neighborhood history, a visual activity, a read-along audio, a short video, and a Chicago neighborhood star activity. Every week, a new challenge will be posted. The resources for this challenge come from our very own Chicago Literacies Program curriculum with CPS schools. You can read more about the program here https://www.chicagohistory.org/education/chiliteracies/. Introduction Chicago is the third-largest city in the United States. The city is made up of more than 200 neighborhoods and 77 community areas. The boundaries of some neighborhoods and communities are part of a long debate. Chicago neighborhoods and communities are grouped into 3 different areas or sides. The Southside, Northside, and Westside are used to divide the city of Chicago. There is no east side because lake Michigan is east of the city. These three sides surround the city’s downtown area, or the Loop, and have been home to different groups of people. The Southside The Southside of Chicago is geographically the largest of all the sides. Some of the neighborhoods that are part of the Southside include Back of the Yards, Bridgeport, Hyde Park, Kenwood, Beverly, Mount Greenwood and many more. -

History of Chicago's Alleys

Living History of Illinois and Chicago® Living History of Illinois and Chicago® – Facebook Group. Digital Research Library of Illinois History® Living History of Illinois Gazette - The Free Daily Illinois Newspaper. Illinois History Store® – Vintage Illinois and Chicago logo products. The History of Chicago's Alleys. Chicago is the alley capital of the country, with more than 1,900 miles of them within its borders. Quintessential expressions of nineteenth-century American urbanity, alleys have been part of Chicago's physical fabric since the beginning. Eighteen feet in width, they graced all 58 blocks of the Illinois & Michigan Canal commissioners' original town plat in 1830, providing rear service access to property facing the 80-foot-wide main streets. Originally Chicago alleys were unpaved, most had no drainage or connection to the sewer system, leaving rainwater to simply drain through the gravel or cinder surfacing. Some heavily used alleys were paved with Belgian wood blocks. Before Belgian block became common, there were many different pavement methods with wildly varying 1 Living History of Illinois and Chicago® Living History of Illinois and Chicago® – Facebook Group. Digital Research Library of Illinois History® Living History of Illinois Gazette - The Free Daily Illinois Newspaper. Illinois History Store® – Vintage Illinois and Chicago logo products. advantages and disadvantages. Because it was so cheap wood block was one of the favored early methods. Chicago street bricks were also used and then alleys were paved over with concrete or asphalt paving. But private platting soon produced a few blocks without alleys, mostly in the Near North Side's early mansion district or in the haphazardly laid-out industrial workingmen's neighborhoods on the Near South Side. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Developing a Voice the Evolution of Self-Determination in an Urban Indian Community David R

Developing a Voice The Evolution of Self-Determination in an Urban Indian Community David R. M. Beck ore American Indians live in urban areas than anywhere Melse in the United States, a fact that the larger American population has been slow to comprehend. Over the past half century this demograph- ic shift from reservation to city has been a factor of steadily increasing significance in shaping the modern Indian experience in America. The implications have been broad-ranging at the community level on reser- vations and in urban centers, and on the individual level for tribal members in both reservation and nonreservation communities. The American Indian population, despite a significant growth spurt,1 has remained below 1 percent of the total U.S. population. Not- withstanding these small numbers, tribes that are federally or state- recognized have been able to advocate with some success for their own needs. They do this based on the semisovereign status accorded to them under the law. Tribes’ ability to do this improved markedly in the era of self-determination, which encompasses the last quarter to third of the twentieth century, although gaps still exist among tribes and in terms of definitions of sovereign rights. WICAZO SA REVIEW 117 “Self-determination” is in the narrow sense a term with legal im- plications in which the federal government recognizes the authority of tribes to govern themselves under the political and judicial definitions of limited sovereignty. In a larger sense, self-determination means the 2002 FALL ability of a people to determine the direction of their own society and community in political, economic, social, and spiritual arenas. -

Collection Overview

Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 Collection Overview The Gerber/Hart archives focuses its collections on gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer life in the Chicago metropolitan area and the Midwest. It contains over 150 collections of historically significant personal manuscripts, photographs, audiovisual recordings, and organizational records. These collections include unpublished material such as letters, diaries, and scrapbooks documenting the lives of both average people and community leaders. They also include the records of many community organizations, businesses, and political campaigns. This guide is intended to serve as a preliminary research tool that provides a brief description of holdings with basic information on size, inclusive dates, types of records, and broad subject areas. Guide Contents List of Collections..............................................................................................................................................2 Collections Descriptions....................................................................................................................................6 Name Index......................................................................................................................................................26 Topical Index...................................................................................................................................................34 1 Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 List of Collections -

Final Copy Abstract

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “ABORIGINALLY YOURS”: THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN INDIANS AND U.S. CITIZENSHIP, 1890-1924 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By PATRICIA LEE FURNISH Norman, Oklahoma 2005 UMI Number: 3203322 Copyright 2005 by Furnish, Patricia Lee All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3203322 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 “ABORIGINALLY YOURS”: THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN INDIANS AND U.S. CITIZENSHIP, 1890-1924 A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Gary C. Anderson ______________________________ R. Warren Metcalf ______________________________ Clara Sue Kidwell ______________________________ David W. Levy ______________________________ Karl F. Rambo © Copyright by PATRICIA LEE FURNISH 2005 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements I am indebted to my late parents, children of the Great Depression, for encouraging my studies. As their only child, I know they believed education to be central to my economic security as an adult. A small handful of public school teachers helped me learn how to learn, what should be one of the foundational features of education. They are Mrs. Taylor, Mrs. Retter, Mrs. Cantrell, Mrs. Barnocky, and most influential, Mrs. Sarah Miller and Mr. Vernon Taylor (both history teachers). I must also credit the late Norma Krider for teaching me how to type. Thanks to Mitzi Foster, Lt. Col. John Regal, Shearle Furnish, Joe Mitchell, Michelle Yelle, Ron Hunt, Heather Clemmer, Sara Eppler Janda, Brett Adams, Lance Allred, Katie Oswalt, Jacqueline Rohrbaugh, Richard Atkins, Susan Kendrick, Geneva and Wayne Beachum, and Jackie Young. -

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

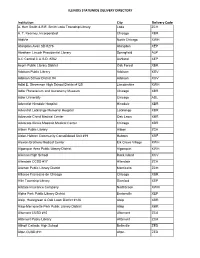

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

Reavis High School Curriculum Snapshot/Cover Page for History of Chicago Unit 1: the Physical Setting Unit 2: City on the Make

Reavis High School Curriculum Snapshot/Cover Page for History of Chicago Unit 1: The Physical Setting Chicago's geographic and geological characteristics will be taught in this unit. Students will gain an understanding of 10 how the area's physical characteristics were formed. The evolution of Chicago and the metropolitan area will also Days be discussed. Other topics covered will be Chicago's grid system and how Chicago compares in size to other metropolitan areas in the United States. Unit 2: City on the Make Students will examine Chicago as the crossroads of economic and cultural exchange from prehistoric time to the present. Students will understand how Native 15 Americans, European explorers, and early Americans Days developed Chicago into a hub of economic and cultural activity. Areas of study will include pre-1871, the I &M Canal, development of the railroad, the Chicago Stockyards, and current economic forces. Unit 3: City in Crisis Students will study how conflicting social, economic, and 15 political forces created disorder and forced changes in the Chicago area. Topics included in this unit will be The Days Chicago Fire, The Haymarket Affair, Al Capone and Prohibition, and the 1968 Democratic Convention. Unit 4: Ethnic Chicago Students will gain an overview of how Chicago's communities have developed over ethnic and racial lines. Students will study past and present community 10 settlement patterns and understand forces that have Days caused changes in these patterns. Other topics of study will include the 1919 and 1968 Race Riots, Jane Addams, and the development of the Reavis community. Unit 5: Unique Chicago Students will explore institutions and personalities that are uniquely Chicago. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2016 GAME 5 - 7:15 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 Gm. 4 - Sat., Oct. 29th CLE 7, CHI 2 Kluber Lackey — 41,706 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) Game 6 at Cleveland (if necessary): Josh Tomlin (13-9, 4.40/2-0/1.76) vs. Jake Arrieta (18-8, 3.10/1-1, 3.78) SERIES AT 3-1 CUBS AND INDIANS IN GAME 5 This marks the 47th time that the World Series stands at 3-1. Of • The Cubs are 6-7 all-time in Game 5 of a Postseason series, the previous 46 times, the team leading 3-1 has won the series 40 including 5-6 in a best-of-seven, while the Indians are 5-7 times (87.0%), and they have won Game 5 on 26 occasions (56.5%).