THE FABRICATION of ISRAEL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Apercevoir La Ville. Pour Une Histoire Des Villes Palestiniennes, Entre Monde Et Sentiment National (1900-2002) Sylvaine Bulle

Apercevoir la ville. Pour une histoire des villes palestiniennes, entre monde et sentiment national (1900-2002) Sylvaine Bulle To cite this version: Sylvaine Bulle. Apercevoir la ville. Pour une histoire des villes palestiniennes, entre monde et senti- ment national (1900-2002). Sociologie. Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), 2004. Français. tel-00766400 HAL Id: tel-00766400 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00766400 Submitted on 19 Dec 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ECOLE DES HAUTES ETUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES Thèse pour l´obtention du titre de Docteur de l´EHESS Discipline : Histoire et Civilisations présentée et soutenue publiquement par Sylvaine BULLE Apercevoir la ville : pour une histoire urbaine palestinienne, entre monde et patrie, sentiment et influences (1920-2002) Directeur de thèse : Jean-Louis COHEN Jury : Mr Rémi Baudouï Mr Jean-Louis Cohen Mr Jean-Charles Depaule Mr Marc Ferro Me Nadine Picaudou Mr Kapil Raj SOMMAIRE Introduction 1. Le monde palestinien 2. Apercevoir la ville. Hypothèses et méthodes, repérage Première partie L´internationale urbaine ou la rencontre manquée en Palestine (1920-1948) 1. le Mandat anglais en Palestine : La dernière présence des Lumières au Levant 2. -

Israeli Nonprofits: an Exploration of Challenges and Opportunities , Master’S Thesis, Regis University: 2005)

Israeli NGOs and American Jewish Donors: The Structures and Dynamics of Power Sharing in a New Philanthropic Era Volume I of II A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies S. Ilan Troen, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Eric J. Fleisch May 2014 The signed version of this form is on file in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. This dissertation, directed and approved by Eric J. Fleisch’s Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Malcolm Watson, Dean Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Committee: S. Ilan Troen, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Jonathan D. Sarna, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Theodore Sasson, Department of International Studies, Middlebury College Copyright by Eric J. Fleisch 2014 Acknowledgements There are so many people I would like to thank for the valuable help and support they provided me during the process of writing my dissertation. I must first start with my incomparable wife, Rebecca, to whom I dedicate my dissertation. Rebecca, you have my deepest appreciation for your unending self-sacrifice and support at every turn in the process, your belief in me, your readiness to challenge me intellectually and otherwise, your flair for bringing unique perspectives to the table, and of course for your friendship and love. I would never have been able to do this without you. -

Hussein. 2009. Adaptation to CC in the Jordan River Valley

COLLEGE OF EUROPE NATOLIN (WARSAW) CAMPUS EUROPEAN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES Adaptation to Climate Change in the Jordan River Valley: the Case of the Sharhabil Bin Hassneh Eco-Park Supervisor: Thierry Béchet Thesis presented by Hussam Hussein for the Degree of Master in Arts in European Interdisciplinary Studies Academic year 2009/2010 1 Statutory Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis has been written by myself without any external un -authoriz ed help, that it has been neither submitted to any institution for evaluation nor previously published in its entirety or in parts. Any parts, words or ideas, of the thesis, however limited, and including tables, graphs, maps etc., which are quoted from or based on other sources, have been acknowledged as such without exception. Moreover, I have also taken note and accepted the College rules with regard to plagiarism (Section 4.2 of the College study regulations). 2 Key words Jordan Adaptation Climate Change Middle East Water 3 Abstract The topic of this thesis, titled Adaptation to Climate Change in the Jordan River Valley: the Case of the Sharhabil Bin Hassneh Eco-Park , is to examine possible solutions of development projects to help the Jordan River Valley to adapt to the impacts that climate change will have in particular to the natural resources in the valley. This analysis is based on research made on the field, collaborating with the environmental NGO Friends of the Earth Middle East . Therefore, many interviews with local people of the communities of the valley, with staff members of the NGO, as well as with important experts such as the former Jordanian Minister of Water and Irrigation Munther Haddadin, were precious in giving some important insight remarks and showing the situation from different point of views. -

Targeted Exclusion at Israel's External Border Crossings

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2016 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Pomona College Recommended Citation Goss, Alexandra, "Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings" (2016). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 166. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/166 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Goss 1 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Readers: Professor Heidi Haddad Professor Zayn Kassam In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in International Relations at Pomona College Pomona College Claremont, CA April 29, 2016 Goss 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Introduction...............................................................................................5 I. Israel: State of Inclusion; State of Exclusion................................................5 II. Background of the Phenomenon...................................................................9 -

Students Discuss People: Usage of Biographical Content in History Lessons

Students Discuss People: Usage of Biographical Content in History Lessons Thesis for the degree of "Doctor of Philosophy" By Michal Honig Submitted to the senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem June 2019 Students Discuss People: Usage of Biographical Content in History Lessons Thesis for the degree of "Doctor of Philosophy" By Michal Honig Submitted to the senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem June 2019 This work was carried out under the supervision of Dr. Dan Porat Abstract This study examines the educational significance of incorporating biographical content in history teaching. It explores various ways in which history teachers referred to well-known historical figures and ordinary people in history lessons, and how their students responded to deliberate integration of biographical texts in these lessons. The objective was to examine the outcomes of including such content in history teaching, both in developing disciplinary skills and in creating a basis for student engagement in history lessons. This qualitative study was conducted in eleven high-school classes in five state schools in Israel. Data were collected from history lesson observations, interviews with teachers, and focus groups in which students were exposed to biographical contents. The data were documented both digitally and in field diaries. Data analysis was conducted in four stages. 1. Initial reading of the transcriptions of the lessons to identify relevant discourse units. 2. Constructing an initial coding scheme based on the themes emerging from the transcriptions. 3. Examining the coding scheme by additional readers and revising it following their comments. 4. Analyzing the transcriptions by several readers to construct common interpretative lines. -

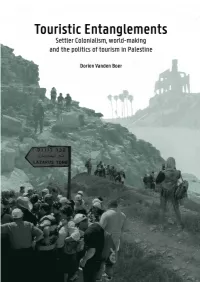

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

September 5, 2018 Kol Haneshamah #947 Draft 4 Date of Tour: July 3-13

September 5, 2018 Kol HaNeshamah #947 Draft 4 Date of tour: July 3-13, 2019 Trip details Number of participants: TBD Welcome to Israel! Arrive at Ben Gurion Transfer to Jerusalem and check into your hotel. Day 1: Wednesday, Orientation at the hotel with Shehechiyanu to bless the beginning of your journey July 3 together in Israel. Opening Dinner at a restaurant near the hotel Overnight: Jerusalem- Mt. Zion Hotel Jerusalem- Holy to All Breakfast at the hotel Day 2: Thursday, July 4 Begin at the Haas Promenade with its panoramic view of Jerusalem. Consider the complexity of Jerusalem’s borders and populations. Encompass the Old City of Jerusalem by following the Ramparts Walk. Walk on the top of the walls built by the Ottoman ruler, Sultan Suliman the Magnificent in 1536, and observe the views of both the Old City as well as the New City. Tour the Jewish Quarter of the Old City and uncover the layers of Jewish history from the time of the First Temple until the present day. Reflect at the Kotel, tour the Davidson Center and head underneath the Old City’s chaotic maze of buildings to the Western Wall Tunnels. You be given time to buy lunch on your own. Continue to the Christian Quarter to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and to the Muslim Quarter to walk through the market and have some tastes of the Old City. Machane Yehuda Tasting Tour- explore the biggest and most famous Shuk in Israel! Meet shop owners, hear how the market has transformed, and taste its unique treats. -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, JUNE 29TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 340 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART Including Judaic Ceremonial Art: From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. And a Collection of Holy Land Maps and Views To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 29th June, 2004 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 27th June: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 28th June: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 29th June: 10:00 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our New Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Sheldon” Sale Number Twenty Four. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 224 Manuscripts: Lots 225 - 271 Holy Land Maps: Lots 272 - 285 Ceremonial Art:s Lots 300 - End of Sale Front Cover: Lot 242 Rear Cover: A Selection of Bindings List of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale. -

PROHIBITION on MONEY LAUNDERING LAW, 5760 - 2000 Unofficial Translation

PROHIBITION ON MONEY LAUNDERING LAW, 5760 - 2000 Unofficial Translation Chapter 1: Interpretation Definitions 1. "Gems" - a stone listed in Schedule 1.1; "Precious stones" - gems or diamonds, whether set in jewelry or in other objects or not, unless they have been integrated or are intended to be integrated into work tools; "Controlling measures", in a corporation - any one of the following: (1) The right to nominate authorized signatories on behalf of the corporation, who can direct, through their signatory rights, the activities of the corporation, with the exception of nominating rights which are given to the board of directors or to the general assembly of the company or similar bodies of a different corporation; (2) The right to vote in the general assembly of the company or a similar body in a different corporation; (3) The right to nominate directors of a company or equivalent senior officer positions in a different corporation, or the managing director of the corporation; (4) The right to participate in the corporation's profits; (5) The right to a share in the remaining assets of a corporation after removal of its debt, during its dissolution; "Stock exchange" - as defined in Section 1 of the Securities Law ; "The Postal Bank" - the company as defined in the Postal Authority Law, 5746- 1986, in its capacity as a provider of financial services as defined in that Law, through the subsidiaries as defined in Section 88K of said Law; "Controlling person" - (1) An individual who has the power to direct the activities of a corporation, -

Download The

Jerusalem: Correcting the International Discourse How the West Gets Jerusalem Wrong Nadav Shragai Published by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Other ebook titles by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: Israel's Critical Security Requirements for Defensible Borders Israel's Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Iran: From Regional Challenge to Global Threat The "Al-Aksa Is in Danger" Libel: The History of a Lie Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] - www.jcpa.org ISBN: 978-147-639-110-6 * * * * * Contents Foreword Part I – The Dangers of Dividing Jerusalem Jerusalem: An Alternative to Separation from the Arab Neighborhoods Part II – Israeli Rights in Jerusalem: Seven Test Cases 1. The Mount of Olives in Jerusalem: Why Continued Israeli Control Is Vital 2. The Palestinian Authority and the Jewish Holy Sites in the West Bank: Rachel's Tomb as a Test Case 3. The City of David and Archeological Sites 4. The Most Recent Damage to Antiquities on the Temple Mount 5. Building in Jerusalem: – The Sheikh Jarrah-Shimon HaTzadik Neighborhood 6. Protecting the Contiguity of Israel: The E-1 Area and the Link Between Jerusalem and Maale Adumim 7. The Mughrabi Gate to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem: The Urgent Need for a Permanent Access Bridge Part III – Demography, Geopolitics, and the Future of Israel's Capital Jerusalem's Proposed Master Plan Notes About the Author About the Jerusalem Center * * * * * Foreword The Holy City of Jerusalem is one of the most contentious facets of the Arab- Israel conflict.