An Exploration of Space, Text, Performativity, Gender and Becoming in Senior Secondary Drama Classrooms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Linn Lounge Presents... the Rolling Stones

Linn Lounge Presents... The Rolling Stones Welcome to Linn Lounge presents… ‘The Rolling Stones’ Tonight’s album, ‘Grr’ tells the fascinating ongoing story of the Greatest Rock'n'Roll Band In The World. It features re-masters of some of the ‘Stones’ iconic recordings. It also contains 2 brand new tracks which constitute the first time Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood have all been together in the recording studio since 2005. This album will be played in Studio Master - the highest quality download available anywhere, letting you hear the recording exactly as it left the studio. So sit back, relax and enjoy as you embark on a voyage through tonight’s musical journey. MUSIC – Muddy Waters, Rollin’ Stone via Spotify (Play 30secs then turn down) It all started with Muddy Waters. A chance meeting between 2 old friends at Dartford railway station marked the beginning of 50 years of rock and roll. In the early 1950s, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger were childhood friends and classmates at Wentworth Primary School in Kent until their families moved apart.[8] In 1960, the pair met again on their way to college at Dartford railway station. The Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters records that Jagger carried revealed a mutual interest. They began forming a band with Dick Taylor and Brian Jones from Blues Incorporated. This band also contained two other future members of the Rolling Stones: Ian Stewart and Charlie Watts.[11] So how did the name come about? Well according to Richards, Jones christened the band during a phone call to Jazz News. -

Emotional Rescue This Was Not an Album Cover That People Loved. Fan

Emotional Rescue This was not an album cover that people loved. Fan reaction was typified by comments like, “this messy cover,” “It may have the single ugliest cover artwork of any record ever released by a major rock artist,” “I still hate the album cover,” “It's butt-ugly,” “I hate the cover,” “The cover is a big part of its poor reception.” “The sleeve was a big let-down after Some Girls, also the waste of time poster included,” “Yeah, I hated the cover…I like covers that show the band...like Black and Blue,” “I can't defend the thermal photography, or whatever it is, that adorns the cover of Emotional Rescue - was Mick on heroin when he signed off on this concept?” "Everyone to his own taste," the old woman said when she kissed her cow. It seems the Stones may have kissed a cow on this album cover. The Title You can always name it after a song on the album. That worked for Let It Bleed, It’s Only Rock and Roll and Some Girls. There were a lot of songs left over from the Some Girls sessions so this album began life with cynical working titles like Certain Women a clear play on the Some Girls title and More Fast Ones an obvious allusion to the pace of the contents. As the album began to take shape it took on the working title of Saturday Where The Boys Meet, a bit of a theme from the song “Where the Boys Go,” which appeared on the album. -

JF07-National Copy.Indd

Girl Power What has changed for women—and what hasn’t by HARBOUR FRASER HODDER Illustrations by ANNIE BISSETT hen dan kindlon watches since the early 1980s. He began to think of them as “alpha girls.” the Tigers play softball, he sees These girls—Kindlon uses the term because his research fo- the legacy of feminism for girls. cuses on female development up to age 21, the period covered by “My daughter’s concentrating on pediatric medicine—were not the self-loathing, melancholic catching the ball, and this other girl teens at risk portrayed in such former bestsellers as Schoolgirls: just slams into her, slides under,” he Young Women, Self-Esteem and the Confidence Gap (Peggy Orenstein), recalls. “Julia got hurt a little bit, she Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls (Myra and David got scraped up, but it was an experi- Sadker), and Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls (Mary ence that used to be exclusively the province of men and boys— Pipher). Girls today “take it for granted that it is their due to get Wto get knocked down, and then you’ve got to pick yourself back equal rights,” Kindlon says. “They never had to fight those battles up and get back in the game, brush your tears o≠, and ignore the over fertility control, equal educational and athletic access, or ille- blood. She was kind of proud of herself afterwards. It was a gal job discrimination.” As a result, “girls are starting to make the character-building experience that very few girls growing up in psychological shift, the inner transformation, that Simone de an earlier generation had a chance to have. -

Albums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts the Rolling Stones

Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling Stones 1 2 3 4 04/1964 3 1 12 11 11/1964 3 12/1964 4 01/1965 1 3101 The Rolling Stones (England's 12 X 5 Around And Around Rolling Stones No. 2 Newest Hit Makers) 5 6 7 8 04/1965 5 08/1965 2 2 1 3 11/1965 1 4 12/1965 4 The Rolling Stones, Now! Out Of Our Heads Bravo Rolling Stones December's Children (And Everybody's) 9 10 11 12 04/1966 1 881 2 04/1966 4 3 01/1967 6 01/1967 2 Aftermath Big Hits (High Tide And Green Got Live If You Want It The Rolling Stones Live Grass) 13 14 15 16 01/1967 2 3 2 08/1967 7 3 12/1967 4 3 2 12/1968 8 3 5 Between The Buttons Flowers Their Satanic Majesties Request Beggars Banquet Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling Stones 17 18 19 20 09/1969 13 2 2 12/1969 3 1 1 3 09/1970 6 1 2 6 04/1971 30 4 Through The Past Darkly (Big Let It Bleed Get Yer Ya‐Ya's Out! Stone Age Hits Vol. 2) 21 22 23 24 04/1971 1 351 1 409/1971 19 01/1972 3 4 03/1972 14 Sticky Fingers Gimme Shelter Hot Rocks 1964 ‐ 1971 Milestones 25 26 27 28 05/1972 2 1 241 11/1972 41 01/1973 9 09/1973 2 1 241 Exile On Main Street Rock'n'Rolling Stones More Hot Rocks (Big Hits & Goat's Head Soup Fazed Cookies) 29 30 31 32 10/1974 12 2 1 1 06/1975 45 8 06/1975 14 6 12/1975 7 It's Only Rock'n'roll Metamorphosis Made In The Shade Rolled Gold ‐ The Very Best Of The Rolling Stones Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling -

For Black Girls Too Fast Too Furious: Black Girlhood & School Discipline

Richardson 1 For Black Girls Too Fast Too Furious: Black Girlhood & School Discipline Senior Research Thesis Presented to the Faculty of The School of Arts & Sciences Brandeis University Department of African & African American Studies Chad Williams, Advisor The Women, Gender & Sexuality Studies Program Shoniqua Roach, Advisor In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Victoria Richardson May 2020 Copyright by Victoria Richardson Committee Members Professor Chad Williams Signature:__________________________ Professor Shoniqua Roach Signature:__________________________ Professor Derron Wallace Signature:__________________________ Richardson 2 Acknowledgment I dedicate my senior thesis to my younger sister, my niece, to Black girls I know, to Black girls I don't know at all, and to the younger version of myself. There will be moments when you don't feel seen, you don't feel heard, you don't feel protected or cared for. This work is for those moments. This work is my expression of love and care for you. This is my reminder to you that you are powerful. You are capable. Stand in your truth. Unapologetically. As I complete this work in the midst of a pandemic I must express my gratitude for my health. I am eternally grateful to be well enough to see this project to the end. I hold in my heart closely all the loved ones we lost during this trying time. I take this space to honor the memory of my grandmother Joyce. You have motivated me to finish this project when I didn't think I was strong enough to do so. -

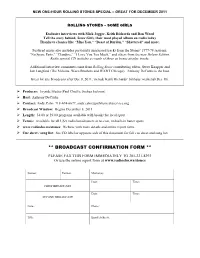

Broadcast Confirmation Form **

NEW ONE-HOUR ROLLING STONES SPECIAL – GREAT FOR DECEMBER 2011 ROLLING STONES – SOME GIRLS Exclusive interviews with Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Ron Wood Tell the story behind, Some Girls, their most played album on radio today Thanks to classics like “Miss You,” “Beast of Burden,” “Shattered” and more. Featured music also includes previously unreleased tracks from the Stones’ 1977-78 sessions, “No Spare Parts,” “Claudine,” “I Love You Too Much,” and others from the new Deluxe Edition. Radio special CD includes a couple of these as bonus airplay tracks. Additional interview comments come from Rolling Stone contributing editor, Steve Knopper and Jon Langford (The Mekons, Waco Brothers and WXRT Chicago). Anthony DeCurtis is the host. Great for any broadcasts after Dec 8, 2011, include Keith Richards’ birthday weekend (Dec 18). Ø Producer: Joyride Media (Paul Chuffo, Joshua Jackson) Ø Host: Anthony DeCurtis Ø Contact: Andy Cahn, 718-674-6677, [email protected] Ø Broadcast Window: Begins December 8, 2011 Ø Length: 54:00 or 59:00 programs available with breaks for local spots Ø Terms: Available for all USA radio broadcasters at no cost, no built-in barter spots. Ø www.radiosho.ws/stones: Website with more details and online report form. Ø Cue sheet / song list: See CD label or opposite side of this document for full cue sheet and song list. ** BROADCAST CONFIRMATION FORM ** PLEASE FAX THIS FORM IMMEDIATELY TO 201-221-8393 Or use the online report form at www.radiosho.ws/stones Station: Format: Market(s): Date: Time: FIRST BROADCAST Date: Time: SECOND BROADCAST Name: Phone: Title: Email Address: The Rolling Stones: Some Girls Special Timings & Cues 59 minute version 1. -

The Rolling Stones - Emotional Rescue (1980) {Japan Mini LP, TOCP-66457}.Rar >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1)

The Rolling Stones - Emotional Rescue (1980) {Japan Mini LP, TOCP-66457}.rar >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) 1 / 3 The,album,of,The,Rolling,Stones.,.,Originally,released,in,1980.,Japanese,Mini,LP,CD,with,OBI.,.In,,,19 80,,,Jagger,,,divorced,,,Bianca,,,Jagger,,,and,,,went,,,on,,,to,,,record,,,and,,,release,,,"Emotional,,,Res cue",,,with,,,The,,,Rolling,,,Stones,,,.,,,from,,,the,,,Emotional,,,Rescue,,,album,,,.,,,Mick,,,Jagger,,,.Find ,,great,,deals,,on,,eBay,,for,,rolling,,stones,,emotional,,rescue,,lp,,.,,ROLLING,,STONES-EMOTION,,AL,, RESCUE-JAPAN,,MINI,,.,,THE,,ROLLING,,STONES,,"Emotional,,Rescue",,1980,,JAPAN,,.Beginning,,,of,,,a, ,,dialog,,,window,,,,including,,,tabbed,,,navigation,,,to,,,register,,,an,,,account,,,or,,,sign,,,in,,,to,,,an,,, existing,,,account.,,,Both,,,registration,,,and,,,sign,,,in,,,support,,,using,,,google,,,..,,,The,,,Rolling,,,St ones,,,released,,,their,,,first,,,studio,,,album,,,in,,,.,,,Emotional,,,Rescue.,,,Year:,,,1980.,,,Some,,,Girls,, ,(1999,,,.,,,Japan,,,Mini,,,Lp),,,Year:,,,1964.,,,The,,,Rolling,,,Stones.2yo,,,Bathtime,,,Girl,,,Being,,,Taugh t,,,B's,,,Page,,,on,,,.,,,2yo,,,Bathtime,,,Girl,,,Being,,,Taught,,,By,,,.,,,Emotional,,,Rescue,,,(1980),,,{Jap an,,,Mini,,,LP,,,,TOCP-66457}.rar,,,El,,,pacto,,,de,,,gracia,,,.The,,Rolling,,Stones,,The,,Rolling,,Stones,,( 1964),,Add,,to,,favorites,,Delete,,from,,favoritesBeginning,of,a,dialog,window,,including,tabbed,navig ation,to,register,an,account,or,sign,in,to,an,existing,account.,Both,registration,and,sign,in,support,us ing,google,.Rolling,,Stones,,-,,Emotional,,Rescue,,:,,Tracklist,,(Vinyl),,A1,,.,,Emotional,,Rescue,,is,,nev -

The Chris Kimsey Interview

AUDIO FOR POST, BROADCAST, RECORDING AND MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION V7.8 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2008 The Chris Kimsey interview Why MySpace Music and social networks mean new revenue Barry Fox investigates the UK radio mic spectrum storm Room-within-room construction considerations Jean Goudier: top film sound practitioner Meet your maker: Colin McDowell — McDSP REVIEWS: Analogue Tube AT-101 • HHB CDR-882 • UA Twin-Finity SPL Phonitor • Manger Zerobox 109 • AKG C214 • Thermionic Rooster craft been working with Arabel Von Karajan (daughter of conductor Herbert). He formed a production company Chris Kimsey in the US with two partners and they have signed Very Emergency from Kentucky and Saint Jude from His work is known to many and his contribution has been enormous to what were in many cases London, both of which Kimsey produced. He had just finished a major three-month project for a Russian difficult projects. GEORGE SHILLING talks to Chris Kimsey about The Stones and others… artist and was just about to mix Chris Jagger’s new album when Resolution caught up with him. (Photos lthough not particularly a fan of rock bands, Kimsey took over, subsequently working on many www.recordproduction.com) Chris Kimsey was initially interested in film more Hallyday albums. Further projects included music and helped out with the music for Peter Frampton, Ten Years After, and he engineered Is it true that Charlie Watts won’t hit his drums his school plays. After pestering the studio some of the Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers album. for you to work on the sound? Amanager he landed a job at Olympic Studios — Keith When Glyn Johns decided to quit working with You’ve got to get the sound while he’s performing, you Grant showed him around and offered him the the Stones, Kimsey was the natural successor. -

Ronnie Wood, Keith Richards, and Mick Jagger by S.L

The Retort - Wednesday, February 17, 1993 Revelations Editor Greg Chinberg - 2195 Solo Stones: Ronnie Wood, Keith Richards, and Mick Jagger By S.L. Maasch the album to an immediate rousing boil as Retort Revelations Writer Jagger rages with cyclonic fury, "I'm hard as a The Rolling Stones. The mere mentioning brick / I hope I never go limp." There's the of that name brings to mind the distinctive reckless declaration of independence of the Jagger vocals, the metallic whiplash of Richards' rockin' title track and the vocal duet of Jagger and Ron Wood's guitars, and the elementary and Lenny Kravitz doing a cover of Bill bass-and-drums thunder of Bill Wyman and Withers's 1970's hit song, "Use Me". His Charlie Watts. brashness and swagger are well intact on num- Though the Stones are set to regroup later bers like "Put Me In The Trash" and the relent- this year for yet another new studio album, they lessly strutting cover ofJames Brown's "Think". aren' t ones to sit on their laurels. Recently, three The first single, "Sweet Thing", has Jagger of them put out solo albums and have proven applying a "Fool To Cry" falsetto to a danceable, that they are far from being merely three oldies "Miss You"- style track. On "Out Of Focus", a acts. It's startling to hear rock' n roll so alive and churchy piano-vocal intro segues into a kind of passionate from players whose ages hover near gospel-funk. "Don't Tear Me Up" is a sadder- fifty and who come trailing chains of history, but-wiserreflection bolstered byechoes of "You myth and cash. -

10 Second Life and the Dynamics of Revival: the Stones After 1989

10 Second Life and the Dynamics of Revival: The Stones after 1989 victor coelho 1989 marked the end of one career and the beginning of another for the Rolling Stones. The year capped almost a decade of disharmony and uneven musical production –“Giants Enter a Deep Sleep” is how Elliott describes this period1 – and witnesses the most acrimonious chapter in the venerable Jagger/Richards partnership, one of the most creative collabora- tive musical relationships in popular music history. Although the decade began with a successful tour in 1981–82 to promote the album Tattoo You, memorialized in the pastel-heavy Hal Ashby-produced film Let’s Spend the Night Together, the animosity within the entire band continued into the mid-1980s. With Richards’ addictions and resultant legal troubles reaching a critical stage, control of the group tilted decisively (and understandably) in the direction of Jagger, who remained resolutely in charge. As producer Chris Kimsey remembers from the recording sessions of their grunge- and funk-influenced album Undercover (1983), When we got to making Undercover, that was the worst time I’d ever experienced with them ...We recorded a lot of it in Nassau [Bahamas], then mixed it in New York, at the Hit Factory. I would get Mick in the studio from like, midday until seven o’clock, then Keith from like, nine o’clock till five in the morning. They would not be together. They specifically avoided each other. Mick would say, “When’s he coming in? I’ll be there later.” After about a week, it was killing me. -

The Preface 2002

The First Forty Years A Book In The Cyber Age (Planned Book Preface, 2002) Each edition of my Rolling Stones discography so far has been preceded by the success of one or more new media formats. For my 1985 book Heart Of Stone it was the VHS tape, for the 1996 publication it was the CD and this time it is the CD-R, the DVD and the Internet. CD-Rs are not being dealt with here in any detail; suffice it to say that today almost anybody can burn their private copies of existing CDs and CD-Rs, hence it is virtually impossible to say what’s on the market. DVDs are something different, offering the best both in audio and in picture quality. In the past four or five years a number of important Rolling Stones films have officially been released in this fascinating format: “THE STONES IN THE PARK” (originally released in 1969), “GIMME SHELTER” (1970) , “ROLLING STONES LIVE AT THE MAX” (1990), “ROLLING STONES VOODOO LOUNGE” (1995), and “BRIDGES TO BABYLON WORLD TOUR ‘97”/’98”. “LET’S SPEND THE NIGHT TOGETHER” (from 1982) also saw the light of day, at least in Brazil. Only five or six years ago, no-one could foresee the changes the Internet would bring about in our daily lives - and it goes without saying that a lot of information assembled in this book has been gathered from the web. Perhaps just as important: e-mail has made world-wide contacts so much simpler. And I’m glad to say that I have experienced a lot of support and enthusiasm from collectors, authors, musicians and producers from all over the world.