Effects of Name-Dropping on First Impressions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

82755929.Pdf

FEBS Letters 589 (2015) 2931–2943 journal homepage: www.FEBSLetters.org Review The 4D nucleome: Evidence for a dynamic nuclear landscape based on co-aligned active and inactive nuclear compartments ⇑ Thomas Cremer a, , Marion Cremer a, Barbara Hübner a,1, Hilmar Strickfaden b, Daniel Smeets a, ⇑ ⇑ Jens Popken a, Michael Sterr a,2, Yolanda Markaki a, Karsten Rippe c, , Christoph Cremer d, a Biocenter, Department Biology II, Ludwig Maximilians University (LMU), Martinsried, Germany b University of Alberta, Cross Cancer Institute Dept. of Oncology, Edmonton, AB, Canada c German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) & BioQuant Center, Research Group Genome Organization & Function, Heidelberg, Germany d Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), Mainz and Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology (IPMB), University of Heidelberg, Germany article info abstract Article history: Recent methodological advancements in microscopy and DNA sequencing-based methods provide Received 1 April 2015 unprecedented new insights into the spatio-temporal relationships between chromatin and nuclear Revised 19 May 2015 machineries. We discuss a model of the underlying functional nuclear organization derived mostly Accepted 20 May 2015 from electron and super-resolved fluorescence microscopy studies. It is based on two spatially Available online 28 May 2015 co-aligned, active and inactive nuclear compartments (ANC and INC). The INC comprises the com- Edited by Wilhelm Just pact, transcriptionally inactive core of chromatin domain clusters (CDCs). The ANC is formed by the transcriptionally active periphery of CDCs, called the perichromatin region (PR), and the inter- chromatin compartment (IC). The IC is connected to nuclear pores and serves nuclear import and Keywords: 4D nucleome export functions. The ANC is the major site of RNA synthesis. -

The Elucidation of Stress Memory Inheritance in Brassica Rapa Plants

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 21 January 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00005 The elucidation of stress memory inheritance in Brassica rapa plants Andriy Bilichak 1, Yaroslav Ilnytskyy 2, Rafal Wóycicki 2, Nina Kepeshchuk 2,DawsonFogen2 and Igor Kovalchuk 2* 1 Lethbridge Research Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, Canada Edited by: Plants are able to maintain the memory of stress exposure throughout their ontogenesis Shawn Kaeppler, University of and faithfully propagate it into the next generation. Recent evidence argues for the Wisconsin-Madison, USA epigenetic nature of this phenomenon. Small RNAs (smRNAs) are one of the vital Reviewed by: epigenetic factors because they can both affect gene expression at the place of Rajandeep Sekhon, Clemson University, USA their generation and maintain non-cell-autonomous gene regulation. Here, we have Thelma Farai Madzima, Florida State made an attempt to decipher the contribution of smRNAs to the heat-shock-induced University, USA transgenerational inheritance in Brassica rapa plants using sequencing technology. To *Correspondence: do this, we have generated comprehensive profiles of a transcriptome and a small Igor Kovalchuk, Department of RNAome (smRNAome) from somatic and reproductive tissues of stressed plants and their Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, University Drive 4401, untreated progeny. We have demonstrated that the highest tissue-specific alterations in Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada the transcriptome and smRNAome profile are detected in tissues that were not directly e-mail: [email protected] exposed to stress, namely, in the endosperm and pollen. Importantly, we have revealed that the progeny of stressed plants exhibit the highest fluctuations at the smRNAome level but not at the transcriptome level. -

Warning Sines: Alu Elements, Evolution of the Human Brain, and the Spectrum of Neurological Disease

Chromosome Res (2018) 26:93–111 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10577-018-9573-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Warning SINEs: Alu elements, evolution of the human brain, and the spectrum of neurological disease Peter A. Larsen & Kelsie E. Hunnicutt & Roxanne J. Larsen & Anne D. Yoder & Ann M. Saunders Received: 6 December 2017 /Revised: 14 January 2018 /Accepted: 15 January 2018 /Published online: 19 February 2018 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract Alu elements are a highly successful family of neurological networks are potentially vulnerable to the primate-specific retrotransposons that have fundamen- epigenetic dysregulation of Alu elements operating tally shaped primate evolution, including the evolution across the suite of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes of our own species. Alus play critical roles in the forma- that are critical for both mitochondrial and CNS func- tion of neurological networks and the epigenetic regu- tion. Here, we highlight the beneficial neurological as- lation of biochemical processes throughout the central pects of Alu elements as well as their potential to cause nervous system (CNS), and thus are hypothesized to disease by disrupting key cellular processes across the have contributed to the origin of human cognition. De- CNS. We identify at least 37 neurological and neurode- spite the benefits that Alus provide, deleterious Alu generative disorders wherein deleterious Alu activity has activity is associated with a number of neurological been implicated as a contributing factor for the manifes- and neurodegenerative disorders. In particular, tation of disease, and for many of these disorders, this activity is operating on genes that are essential for proper mitochondrial function. -

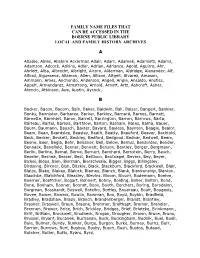

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

Germanic Surname Lexikon

Germanic Surname Lexikon Most Popular German Last Names with English Meanings German for Beginners: Contents - Free online German course Introduction German Vocabulary: English-German Glossaries For each Germanic surname in this databank we have provided the English Free Online Translation To or From German meaning, which may or may not be a surname in English. This is not a list of German for Beginners: equivalent names, but rather a sampling of English translations of German names. Das Abc German for Beginners: In many cases, there may be several possible origins or translations for a Lektion 1 surname. The translation shown for a surname may not be the only possibility. Some names are derived from Old German and may have a different meaning from What's Hot that in modern German. Name research is not always an exact science. German Word of the Day - 25. August German Glossary of Abbreviations: OHG (Old High German) Words to Avoid - T German Words to Avoid - Glossary Warning German Glossary of Germanic Last Names (A-K) Words to Avoid - With English Meanings Feindbilder German Words to Avoid - Nachname Last Name English Meaning A Special Glossary Close Ad A Dictionary of German Aachen/Aix-la-Chapelle Names Aachen/Achen (German city) Hans Bahlow, Edda ... Best Price $16.95 Abend/Abendroth evening/dusk or Buy New $19.90 Abt abbott Privacy Information Ackerman(n) farmer Adler eagle Amsel blackbird B Finding Your German Ancestors Bach brook Kevan M Hansen Best Price $4.40 Bachmeier farmer by the brook or Buy New $9.13 Bader/Baader bath, spa keeper Privacy Information Baecker/Becker baker Baer/Bar bear Barth beard Bauer farmer, peasant In Search of Your German Roots. -

Family Group Sheets Surname Index

PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS SURNAME INDEX This collection of 660 folders contains over 50,000 family group sheets of families that resided in Passaic and Bergen Counties. These sheets were prepared by volunteers using the Societies various collections of church, ceme tery and bible records as well as city directo ries, county history books, newspaper abstracts and the Mattie Bowman manuscript collection. Example of a typical Family Group Sheet from the collection. PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS — SURNAME INDEX A Aldous Anderson Arndt Aartse Aldrich Anderton Arnot Abbott Alenson Andolina Aronsohn Abeel Alesbrook Andreasen Arquhart Abel Alesso Andrews Arrayo Aber Alexander Andriesse (see Anderson) Arrowsmith Abers Alexandra Andruss Arthur Abildgaard Alfano Angell Arthurs Abraham Alje (see Alyea) Anger Aruesman Abrams Aljea (see Alyea) Angland Asbell Abrash Alji (see Alyea) Angle Ash Ack Allabough Anglehart Ashbee Acker Allee Anglin Ashbey Ackerman Allen Angotti Ashe Ackerson Allenan Angus Ashfield Ackert Aller Annan Ashley Acton Allerman Anners Ashman Adair Allibone Anness Ashton Adams Alliegro Annin Ashworth Adamson Allington Anson Asper Adcroft Alliot Anthony Aspinwall Addy Allison Anton Astin Adelman Allman Antoniou Astley Adolf Allmen Apel Astwood Adrian Allyton Appel Atchison Aesben Almgren Apple Ateroft Agar Almond Applebee Atha Ager Alois Applegate Atherly Agnew Alpart Appleton Atherson Ahnert Alper Apsley Atherton Aiken Alsheimer Arbuthnot Atkins Aikman Alterman Archbold Atkinson Aimone -

Surname Folders.Pdf

SURNAME Where Filed Aaron Filed under "A" Misc folder Andrick Abdon Filed under "A" Misc folder Angeny Abel Anger Filed under "A" Misc folder Aberts Angst Filed under "A" Misc folder Abram Angstadt Achey Ankrum Filed under "A" Misc folder Acker Anns Ackerman Annveg Filed under “A” Misc folder Adair Ansel Adam Anspach Adams Anthony Addleman Appenzeller Ader Filed under "A" Misc folder Apple/Appel Adkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Applebach Aduddell Filed under “A” Misc folder Appleman Aeder Appler Ainsworth Apps/Upps Filed under "A" Misc folder Aitken Filed under "A" Misc folder Apt Filed under "A" Misc folder Akers Filed under "A" Misc folder Arbogast Filed under "A" Misc folder Albaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Archer Filed under "A" Misc folder Alberson Filed under “A” Misc folder Arment Albert Armentrout Albight/Albrecht Armistead Alcorn Armitradinge Alden Filed under "A" Misc folder Armour Alderfer Armstrong Alexander Arndt Alger Arnold Allebach Arnsberger Filed under "A" Misc folder Alleman Arrel Filed under "A" Misc folder Allen Arritt/Erret Filed under “A” Misc folder Allender Filed under "A" Misc folder Aschliman/Ashelman Allgyer Ash Filed under “A” Misc folder Allison Ashenfelter Filed under "A" Misc folder Allumbaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Ashoff Alspach Asper Filed under "A" Misc folder Alstadt Aspinwall Filed under "A" Misc folder Alt Aston Filed under "A" Misc folder Alter Atiyeh Filed under "A" Misc folder Althaus Atkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Altland Atkinson Alwine Atticks Amalong Atwell Amborn Filed under -

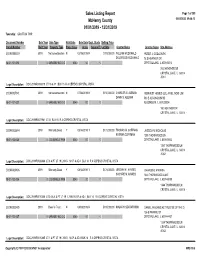

Sales Report

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 309 McHenry County 05/04/2020 09:46:13 01/01/2019 - 12/31/2019 Township: GRAFTON TWP Document Number Sale Year Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Parcel Number Built Year Property Type Prop. Class Acres Square Ft. Lot Size Grantor Name Grantee Name Site Address 2019R0006019 2019 Not advertised on mN 02/19/2019 N $115,000.00 WILLIAM MCDONALD PETER J. GODLEWSKI DOLORESS MCDONALD 78 S HEATHER DR 18-01-101-013 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145018 78 S HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5018 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0006019 LT 16 & 17 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0027941 2019 Not advertised on mN 07/08/2019 N $150,000.00 CHARLES G. ALEMAN REINVEST HOMES LLC, AN ILLINOIS LIMIT DAWN S. ALEMAN 503 E ALGONQUIN RD 18-01-101-027 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 ALGONQUIN, IL 601023004 160 HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 - Legal Description: DOC 2019R0027941 LT 31 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0026844 2019 Warranty Deed Y 08/14/2019 Y $172,000.00 THOMAS M. COFFMAN JESSICA N. NICHOLAS KATRINA COFFMAN 1350 THORNWOOD LN 18-01-102-035 0 LDG SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145042 1350 THORNWOOD LN CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5042 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0026844 LT 6 & PT LT 19 LYING N OF & ADJ BLK 14 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0010406 2019 Warranty Deed Y 04/12/2019 Y $174,000.00 JEREMY M. -

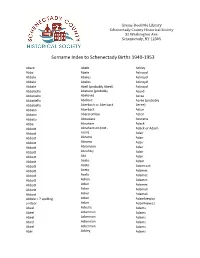

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. -

Start Number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy

Start number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy Frølund Jensen Kongens lyngby, Denmark 89:20:46 11002 Emil Boström Lag Nord Linköping, Sweden 98:19:04 11003 Lovisa Johansson Lag Nord Burträsk, Sweden 98:19:02 11005 Maurice Lagershausen Huddinge, Sweden 102:01:54 11011 Hyun jun Lee Korea, (south) republic of 122:40:49 11012 Viggo Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:24 11013 Richard Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:28 11014 Rasmus Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11015 Rafael Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11017 Marie Zølner Hillerød, Denmark 82:11:49 11018 Niklas Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11019 Viggo Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11020 Damian Sulik #StopComplaining Siegen, Germany 101:13:24 11023 Bruno Svendsen Tylstrup, Denmark 74:48:08 11024 Philip Oswald Lakeland, USA 55:52:02 11025 Virginia Marshall Lakefield, Canada 55:57:54 11026 Andreas Mathiasson Backyard Heroes Ödsmål, Sweden 75:12:02 11028 Stine Andersen Brædstrup, Denmark 104:35:37 11030 Patte Johansson Tiger Södertälje, Sweden 80:24:51 11031 Frederic Wiesenbach BB Dahn, Germany 101:21:50 11032 Romea Brugger BB Berlin, Germany 101:22:44 11034 Oliver Freudenberg Heyda, Germany 75:07:48 11035 Jan Hennig Farum, Denmark 82:11:50 11036 Robert Falkenberg Farum, Denmark 82:11:51 11037 Edo Boorsma Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:34 11038 Trijneke Stuit Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:35 11040 Sebastian Keck TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:01 11041 Tatjana Kage TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:02 11042 Eun Lee -

Human Genetics and Clinical Aspects of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Human genetics and clinical aspects of neurodevelopmental disorders Gholson J. Lyon1,2,3,*, Jason O’Rawe1,3 1Stanley Institute for Cognitive Genomics, One Bungtown Road, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY, USA, 11724 2Institute for Genomic Medicine, Utah Foundation for Biomedical Research, E 3300 S, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 84106 3Stony Brook University, 100 Nicolls Rd, Stony Brook, NY, USA, 11794 * Corresponding author: Gholson J. Lyon Email: [email protected] Other author emails: Jason O'Rawe: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Introduction “our incomplete studies do not permit actual classification; but it is better to leave things by themselves rather than to force them into classes which have their foundation only on paper” – Edouard Seguin (Seguin, 1866) “The fundamental mistake which vitiates all work based upon Mendel’s method is the neglect of ancestry, and the attempt to regard the whole effect upon off- spring, produced by a particular parent, as due to the existence in the parent of particular structural characters; while the contradictory results obtained by those who have observed the offspring of parents apparently identical in cer- tain characters show clearly enough that not only the parents themselves, but their race, that is their ancestry, must be taken into account before the result of pairing them can be predicted” – Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (Weldon, 1902).