The Right to Access DNA Testing by Alleged Innocent Victims of Wrongful Convictions in the United Kingdom?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cymmer & Croeserw

Community Profile – Cymmer & Croeserw Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 The Villages of Cymmer, Croeserw, Abercregan, Dyffryn Rhondda and Cynonville make up the rural ward of Cymmer. They are situated in the east of the Afan Valley, the villages lying approximately 9 miles from the Towns of Port Talbot and Neath. The area is closer to Maesteg and people often travel there for shopping and services as it is easier to get to than Neath or Port Talbot. The villages are located very close to each other – about three quarters of a mile. The local landscape is wooded hills and some farmland. The area is world Entrance to Croeserw renowned for the excellent mountain bike trails. Aerial view of Cymmer looking up the valley The population is, according to the 2011 Census, 2765. This breaks down as 0 – 17 20.8%, 18 - 64 59.5%, 65 and above 19.7%. 988 working age people are economically inactive, this figure, 47.8% been higher than both the NPT average, (29.4%) and Wales (23.0%). 9.7% of the population holds qualifications of Level 4 and above, with the NPT average been 20.8% and Wales as a whole 29.7%. 36.2% of housing is socially rented which is significantly higher than the welsh average of 16.5%. The majority of NPTCBC run facilities are now run and managed by the community. The local comprehensive school closed in July 2019 this has had a devastating impact on the whole valley. Natural Resources Wales manages the forestry in areas of the ward that houses lots of walking and cycling trails. -

Forensic DNA Analysis: Issues

US. Departmentof Justice Officeof JusticeProgmm Bureau of Justice Sta!ktics U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Steven D. Dillingham, Ph.D. Director Acknowledgments. This report was prepared by SEARCH Group, Inc., Gary L. Bush, Chairman, and Gary R. Cooper, Executive Director. The project director was Sheila J. Barton, Director, Law and Policy Program. This report was written by Robert R. Belair, SEARCH General Counsel, with assistance from Robert L. Marx, System Specialist, and Judith A. Ryder, Director, Corporate Communications. Special thanks are extended to Dr. Paul Ferrara, Director, Bureau of Forensic Science, Commonwealth of Virginia. The federal project monitor was Carol G. Kaplan, Chief, Federal Statistics and Information Policy Branch, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Report of work performed under B JS Grant No. 87-B J-CX-K079, awarded to SEARCH Group, Inc., 73 11 Greenhaven Drive, Suite 145, Sacramento, California 95831. Contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views, policies or legal analyses of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U.S. Department of Justice. Copyright O SEARCH Group, Inc. 1991 The U.S. Department of Justice authorizes any person to reproduce, publish, translate or otherwise use all or any part of the copyrighted material in this publication with the exception of those items indicating that they are copyrighted or reprinted by any source other than SEARCH Group, Inc. The Assistant Attorney General, Office of Justice Programs, coordinates the activities of the following program offices and bureaus: the Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Institute of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. -

Tai Tarian – Playing Their Part in a Sustainable Future in 2018, Tai Tarian Joined Wales’ Bee Friendly They Helped Them to Design and Create Bug Initiative

Case Studies Tai Tarian – playing their part in a sustainable future In 2018, Tai Tarian joined Wales’ Bee Friendly They helped them to design and create bug initiative. Tai Tarian is one of the largest hotels, which are located at Baglan. social housing providers in Wales, owning over 9000 properties and managing over Tai Tarian has worked with Buglife Cymru to 450 acres in the Neath Port Talbot County. create wildflower and community woodlands In 2016, with a member of staff fully trained habitats for pollinators along identified to become their resident beekeeper, they ‘B-lines’ (www.buglife.org.uk). They feel installed bee hives at their head office in that the key to success in their projects is Baglan. Following this, they made links with the connections they have made with local local school children and educated them on schools and communities. the importance of bees. Partnership working has given pride and Apprentices employed on their Copper value to the projects, which have enhanced Foundation programme worked with the green spaces and improved biodiversity in children. the Borough. Enhancing our Haven Housing Schemes (independent living for the over 55’s) Initially, Haven Housing tenants were invited to coffee mornings. During these, Clare Dinham (Buglife Cymru) explained the B-Line project and the work required for wildflower planting. The Tai Tarian team encouraged tenants to get involved in whatever way they felt comfortable. This could be helping to prepare ground or sowing seeds. If mobility were an issue, tenants could promote the B-Line projects to friends and families. At several housing schemes, tenants have seen and enjoyed the benefits of wildflower meadows in full bloom. -

Bridgend Local Development Plan

Cyngor Bwrdeistref Sirol r gw O r a t n o b - y Bridgend Local Development Plan - n e P BRIDGEND 2006-2021 County Borough Council Background Paper 1: The National, Regional & Local Context March 2011 NB. Print using Docucolor 250PCL Draft Candidate Site Bridgend Local Development Plan 2006 – 2021 Background Paper One The National, Regional and Local Context March 2011 Development Planning Regeneration and Development Communities Directorate Bridgend County Borough Council Angel Street, Bridgend CF31 4WB 1. Introduction 1.1 This Background Paper is the first in a series of documents which has been prepared by Bridgend County Borough Council to provide information and justification to the contents of the deposit Bridgend Local Development Plan (LDP). 1.2 The Pre-Deposit Proposals document, issued for public consultation between February and March 2009 contained information on the national, regional and local context with a review of the existing situation, policies and practice from various public and private organisations which have an impact or implication for the strategic land-use planning system. This review then continued by highlighting the national, regional and local issues which had been identified in that review which would need to be addressed or acknowledged in the deposit LDP. 1.3 This document represents an updated version of chapters 3-5 of the Pre Deposit Proposals. Updates to the document have occurred for the following reasons: Factual updates resulting from changes to policies since the publication of the Pre Deposit Proposals Changes which were recommended or suggested as a result of representations received during the public consultation on the Pre Deposit Proposals As a result of the above, new or revised issues may have arisen which will be required to be addressed 1.4 The Background Paper does not attempt to précis every piece of national, regional and local policy, relevant to Bridgend County Borough. -

The New Scientific Eyewitness

The New Scientific Eyewitness The role of DNA profiling in shaping criminal justice Jenny Wise A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Criminology 2008 1 Certificate of Originality I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Signed i Copyright Statement I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

71 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

71 bus time schedule & line map 71 Cymmer - Bridgend via Maesteg View In Website Mode The 71 bus line (Cymmer - Bridgend via Maesteg) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bridgend: 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM (2) Cymmer: 7:25 AM - 5:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 71 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 71 bus arriving. Direction: Bridgend 71 bus Time Schedule 62 stops Bridgend Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Turning Circle, Cymmer Tuesday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Police Station, Cymmer Wednesday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Swimming Pool, Croeserw Thursday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Brytwn Road, Glyncorrwg Community Friday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Bethania, Cymmer Lloyd's Terrace, Glyncorrwg Community Saturday 7:14 AM - 5:54 PM Coronation Avenue, Croeserw Coronation Avenue, Glyncorrwg Community Eastern Avenue, Croeserw 71 bus Info Direction: Bridgend Sunny Crescent, Croeserw Stops: 62 Trip Duration: 63 min Church Street, Croeserw Line Summary: Turning Circle, Cymmer, Police Church Street, Glyncorrwg Community Station, Cymmer, Swimming Pool, Croeserw, Bethania, Cymmer, Coronation Avenue, Croeserw, Fairƒeld Road, Croeserw Eastern Avenue, Croeserw, Sunny Crescent, Croeserw, Church Street, Croeserw, Fairƒeld Road, Nant-Y-Fedw Road, Croeserw Croeserw, Nant-Y-Fedw Road, Croeserw, Croeserw Brynheulog Road, Glyncorrwg Community Club, Blaencaerau, Ivy House, Caerau, Cornhill, Caerau, Church, Caerau, War Memorial, Caerau, Croeserw Club, Blaencaerau Farm, Caerau, Bedw Street, Dyffryn, -

Glamorgan's Blood

Glamorgan’s Blood Colliery Records for Family Historians A Guide to Resources held at Glamorgan Archives Front Cover Illustrations: 1. Ned Griffiths of Coegnant Colliery, pictured with daughters, 1947, DNCB/14/4/33/6 2. Mr Lister Warner, Staff Portrait, 8 Feb 1967 DNCB/14/4/158/1/8 3. Men at Merthyr Vale Colliery, 7 Oct 1969, DNCB/14/4/158/2/3 4. Four shaft sinkers in kibble, [1950s-1960s], DNCB/14/4/158/2/4 5. Two Colliers on Surface, [1950s-1960s], DNCB/14/4/158/2/24 Contents Introduction 1 Summary of the collieries for which Glamorgan Archives hold 3 records containing information on individuals List of documents relevant to coalfield family history research 6 held at Glamorgan Archives (arranged by the valley/area) Collieries in Aber Valley 6 Collieries in Afan Valley 6 Collieries in Bridgend 8 Collieries in Caerphilly 9 Collieries in Clydach Vale 9 Collieries in Cynon Valley 10 Collieries in Darren Valley 11 Collieries in Dowlais/Merthyr 13 Collieries in Ebbw Valley 15 Collieries in Ely Valley 17 Collieries in Garw Valley 17 Collieries in Ogmore Valley 19 Collieries in Pontypridd 21 Collieries in Rhondda Fach 22 Collieries in Rhondda Fawr 23 Collieries in Rhondda 28 Collieries in Rhymney Valley 29 Collieries in Sirhowy Valley 32 Other (non-colliery) specific records 33 Additional Sources held at Glamorgan Archives 42 External Resources 43 Introduction At its height in the early 1920s, the coal industry in Glamorgan employed nearly 180,000 people - over one in three of the working male population. Many of those tracing their ancestors in Glamorgan will therefore sooner or later come across family members who were coal miners or colliery surface workers. -

Forensic DNA Analysis

FOCUS: FORENSIC SCIENCE Forensic DNA Analysis JESSICA MCDONALD, DONALD C. LEHMAN LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Television shows such as CSI: Crime Scene 1. Discuss the important developments in the history Investigation, Law and Order, Criminal Minds, and of DNA profiling. many others portray DNA analysis as a quick and 2. Compare and contrast restriction fragment length simple process. However, these portrayals are not polymorphism and short tandem repeat analyses in accurate. Since the discovery of DNA as the genetic the area of DNA profiling. material in 1953, much progress has been made in the Downloaded from 3. Describe the structure of short tandem repeats and area of forensic DNA analysis. Despite how much we their alleles. have learned about DNA and DNA analysis (Table 1), 4. Identify the source of DNA in a blood sample. our knowledge of DNA profiling can be enhanced 5. Discuss the importance of the amelogenin gene in leading to better and faster results. This article will DNA profiling. discuss the history of forensic DNA testing, the current 6. Describe the advantages and disadvantages of science, and what the future might hold. http://hwmaint.clsjournal.ascls.org/ mitochondrial DNA analysis in DNA profiling. 7. Describe the type of DNA profiles used in the Table 1. History of DNA Profiling Combined DNA Index System. 8. Compare the discriminating power of DNA 1953 Franklin, Watson, and Crick discover structure of DNA 1983 Kary Mullis develops PCR procedure, ultimately winning profiling and blood typing. Nobel Prize in Science in 1993 -

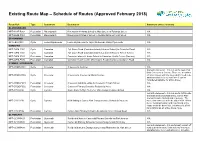

Existing Route Map – Schedule of Routes (Approved February 2018)

Existing Route Map – Schedule of Routes (Approved February 2018) Route Ref: Type Settlement Destination Statement (where relevant) BLAENGWRACH NPT-BLAE-P002 Pedestrian Blaengwrach Blaengwrach Infants School to High Street via Edwards Street N/A NPT-BLAE-P003 Pedestrian Blaengwrach Blaengwrach Primary School to Residential Area / High Street N/A BRYNAMMAN NPT-LBA-C001 Cycle Lower Brynamman Lower Brynamman to Twyn Via Amman Valley Cycle route N/A CWMAFAN NPT-CWM-C001 Cycle Cwmafan Ty'r-Owen Road (Cwmafan Infants & Junior School) to Cwmafan Road N/A NPT-CWM-C002 Cycle Cwmafan Ty'r-Owen Road (Cwmafan Infants & Junior School) to Tarren Terrace N/A NPT-CWM-P003 Pedestrian Cwmafan Cwmafan Infants & Junior School to Cwmafan Health Centre (Doctors) N/A NPT-CWM-P005 Pedestrian Cwmafan Cwmafan Health Centre (Doctors) to Residential Area via Salem Road N/A CYMMER / CROESERW NPT-CROE-C001 Cycle Croeserw Croeserw to Cymmer N/A Fail with statement – this is a useful route that links Croeserw to Caerau. There are a number NPT-CROE-C002 Cycle Croeserw Croeserw to Caerau via Menai Avenue of minor issues with the route which need to be addressed but in its current form it can be considered suitable for active travel. NPT-CROE-P001 Pedestrian Croeserw Croeserw Industrial estate to Croeserw Primary School N/A NPT-CROE-P002 Pedestrian Croeserw Croeserw Primary School to Residential Area N/A NPT-CYM-C002 Cycle Cymmer Route From Duffryn To Cymer Afan Comprehensive School N/A Fail with statement – this is a useful NCN route that acts as an important link to Cymer Afan Comprehensive School and Croeserw. -

2. Data and Definitions Report , File Type

Welsh Government | NDF Regions and Rural Study 2. Data and Definitions Report 264350-00 | ISSUE | 14 March 2019 11 Welsh Government NDF Regions and Rural Areas Study Study Report - Data and Definitions Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 NDF Context 1 1.2 Purpose of this Study and Reports 4 1.3 Structure of this Report 6 2 Data Collection 7 2.1 Baseline Information 7 2.2 Methodology 8 2.3 Stakeholder Engagement 13 2.4 SWOT and data supporting policy development 32 3 Defining ‘Major’ 36 3.1 Employment Sites 36 3.2 Retail / Commercial Sites 40 3.3 Generating Stations 44 3.4 Transport Schemes 44 4 Defining & Mapping Key Settlements 45 4.1 LDP Spatial Strategies 45 4.2 Population 47 4.3 Proposed Approach 48 5 Defining Rural Areas 51 6 Adjoining English Regions 61 6.1 Priority cross border issues 61 6.2 Key drivers 62 6.3 Key considerations 73 7 The Well-being of Future Generations Act 74 8 Summary 77 8.1 Overview 77 8.2 Outcomes 78 8.3 Definitions 78 8.4 Key Settlements 79 8.5 Rural Areas 80 8.6 Adjoining English Regions 80 8.7 The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 81 | Issue | 15 March 2019 J:\264000\264350-00\4 INTERNAL PROJECT DATA\4-50 REPORTS\07. STUDY REPORT\ISSUE DATA DEFINITIONS REPORT.DOCX Welsh Government NDF Regions and Rural Areas Study Study Report - Data and Definitions Appendices Appendix A LPA Information Request Appendix B Data Tables & Map Outputs | Issue | 15 March 2019 J:\264000\264350-00\4 INTERNAL PROJECT DATA\4-50 REPORTS\07. -

DNA Evidence and Police Investigations: a Health Warning

Policeprofessional/May2006 DNA evidence and police investigations: a health warning. Jason Roach and Ken Pease Introduction Much has been made of recent advances in DNA science and technology with particular emphasis placed on its bewildering implications for policing and the detection of serious offenders. Operation Phoenix for example, conducted by Northumbria Police in conjunction with the Forensic Science Service (FSS), has seen a total of 42 named DNA matches obtained against the National DNA Database (NDNAD) for more than 400 unsolved sexual offences over a 14 year period, resulting in 14 convictions up to 2005 (Forensic Science Service Annual Report 2004-05). Both technical advances in DNA serology and the infrastructure of analysis and retention bring forensic DNA analysis into the mainstream of detection, with accompanying public interest. For example the development of Low Copy Number techniques (LCN) now render very small samples usable. The size of the National DNA Database (well over three million by early 2006) aspires to cover the active criminal population. The use of DNA evidence in police investigations stems, as is well known, from the work of Sir Alec Jeffreys and colleagues at Leicester University (see Jeffreys Wilson and Thein 1985), whose generation of images from RFLP1 analysis of unique human DNA were so redolent of supermarket bar codes as to be irresistible to the public mind. Because some twenty years has now elapsed since the first use of the Jeffreys technique it may be worthwhile rehearsing what happened, since it illustrates the central argument of this paper, that the linkages between DNA identification of offenders and the detection task generally is, and must be, subtle in order to optimise detection efficiency. -

70 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

70 bus time schedule & line map 70 Cymmer - Bridgend via Caerau, Maesteg, Garth, View In Website Mode Llangynwyd & Aberkenƒg The 70 bus line (Cymmer - Bridgend via Caerau, Maesteg, Garth, Llangynwyd & Aberkenƒg) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bridgend: 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM (2) Cymmer: 8:20 AM - 5:20 PM (3) Maesteg: 5:50 PM - 6:50 PM (4) Maesteg: 6:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 70 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 70 bus arriving. Direction: Bridgend 70 bus Time Schedule 60 stops Bridgend Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:00 AM - 6:00 PM Monday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Turning Circle, Cymmer Tuesday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Police Station, Cymmer Wednesday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Swimming Pool, Croeserw Thursday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Brytwn Road, Glyncorrwg Community Friday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Bethania, Cymmer Lloyd's Terrace, Glyncorrwg Community Saturday 7:20 AM - 5:50 PM Coronation Avenue, Croeserw Coronation Avenue, Glyncorrwg Community Eastern Avenue, Croeserw 70 bus Info Direction: Bridgend Sunny Crescent, Croeserw Stops: 60 Trip Duration: 54 min Church Street, Croeserw Line Summary: Turning Circle, Cymmer, Police Church Street, Glyncorrwg Community Station, Cymmer, Swimming Pool, Croeserw, Bethania, Cymmer, Coronation Avenue, Croeserw, Fairƒeld Road, Croeserw Eastern Avenue, Croeserw, Sunny Crescent, Croeserw, Church Street, Croeserw, Fairƒeld Road, Nant-Y-Fedw Road, Croeserw Croeserw, Nant-Y-Fedw Road, Croeserw, Croeserw Brynheulog Road, Glyncorrwg Community Club, Blaencaerau, Ivy