Feminist Theory, Autobiography, Edith Wharton, and Me Susan L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory!

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory! So, we’ve hit another milestone. I’ve rated for 15+ before like 6am, when it made 20 episodes of this podcast – which becomes a Top 50 countdown. When I was is frankly very silly – and I was trying younger, it was the quickest way to find to think about what I could write about new music, and potentially accidentally to reflect such a momentous occasion. see something that would really scar I was trying to think of something that you, music-video wise. Like that time I was released in the year 2000 and accidentally saw Aphex Twin’s Come to was, as such, experiencing a similarly Daddy music video. momentous 20th anniversary. The answer is, unsurprisingly, a lot of things But because I was tiny and my brain – Gladiator, Bring It On and American was a sponge, it turns out a lot of what Psycho all came out in the year 2000. But I consumed has actually just oozed into I wasn’t allowed to watch any of those every recess of my being, to the point things until I was in high school, and they where One Step Closer came on and I didn’t really spur me to action. immediately sang all the words like I was in some sort of trance. And I haven’t done And then I sent a rambling voice memo a musical episode for a while. So, today, to Wes, who you may remember from we’re talking Nu Metal, baby! Hell yeah! such hits as “making this podcast sound any good” and “writing the theme tune I’m Alex. -

Hybrid Dynamic Density Functional Theory for Polymer Melts and Blends

Hybrid Dynamic Density Functional Theory for Polymer Melts and Blends Takashi Honda ∗ Japan Chemical Innovation Institute, and Department of Organic and Polymeric Materials, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8552, Japan Toshihiro Kawakatsu Department of Physics, Tohoku University, Aoba, Aramaki, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8578, Japan Abstract We propose a high-speed and accurate hybrid dynamic density functional theory for the computer simulations of the phase separation processes of polymer melts and blends. The proposed theory is a combination of the dynamic self-consistent field (SCF) theory and a time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau type theory with the random phase approximation (GRPA). The SCF theory is known to be accurate in evaluating the free energy of the poly- mer systems in both weak and strong segregation regions although it has a disadvantage of the requirement of a considerable amount of computational cost. On the other hand, the GRPA theory has an advantage of much smaller amount of required computational cost than the SCF theory while its applicability is limited to the weak segregation region. To make the accuracy of the SCF theory and the high-performance of the GRPA theory compati- ble, we adjust the chemical potential of the GRPA theory by using the SCF theory every constant time steps in the dynamic simulations. The performance of the GRPA and the arXiv:cond-mat/0609081v1 [cond-mat.soft] 5 Sep 2006 hybrid theories is tested by using several systems composed of an A/B homopolymer, an AB diblock copolymer, or an ABC triblock copolymer. Using the hybrid theory, we succeeded in reproducing the metastable complex phase-separated domain structures of an ABC triblock copolymer observed by experiments. -

A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor

A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor Relevance Theory and Cognitive Linguistics Markus Tendahl A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Taiwan eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-02 eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect Taiwan - licensed to www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230244313 - A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor, Markus Tendahl This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Taiwan eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-02 eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect Taiwan - licensed to www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230244313 - A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor, Markus Tendahl A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor Relevance Theory and Cognitive Linguistics Markus Tendahl University of Dortmund, Germany Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Taiwan eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-02 eBook Consortium - PalgraveConnect Taiwan - licensed to www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230244313 - A Hybrid Theory of Metaphor, Markus Tendahl © Markus Tendahl 2009 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

A Hybrid Theory of Environmentalism Steve Matthews Charles Sturt University

Essays in Philosophy Volume 3 Article 10 Issue 1 Environmental Aesthetics 1-2002 A Hybrid Theory of Environmentalism Steve Matthews Charles Sturt University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.pacificu.edu/eip Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Matthews, Steve (2002) "A Hybrid Theory of Environmentalism," Essays in Philosophy: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 10. Essays in Philosophy is a biannual journal published by Pacific nivU ersity Library | ISSN 1526-0569 | http://commons.pacificu.edu/eip/ Matthews -- Essays in Philosophy Essays in Philosophy A Biannual Journal Vol. 3 No. 1 A Hybrid Theory of Environmentalism Abstract The destruction and pollution of the natural environment poses two problems for philosophers. The first is political and pragmatic: which theory of the environment is best equipped to impact policymakers heading as we are toward a series of potential eco- catastrophes? The second is more central: On the environment philosophers tend to fall either side of an irreconcilable divide. Either our moral concerns are grounded directly in nature, or the appeal is made via an anthropocentric set of interests. The lack of a common ground is disturbing. In this paper I attempt to diagnose the reason for this lack. I shall agree that wild nature lacks features of intrinsic moral worth, and that leaves a puzzle: Why is it once we subtract the fact that there is such a lack, we are left with strong intuitions against the destruction and/or pollution of wild nature? Such intuitions can be grounded only in a strong sense of aesthetic concern combined with a common-sense regard for the interests of sentient life as it is indirectly affected by the quality of the environment. -

Travel Tracker

Travel Tracker Consumer Behavior Patterns Around the World October 2020 COVID-19: June 1 – Sept 30, 2020 Travel Tracker As the COVID-19 pandemic reaches its eighth month, global sentiment towards the virus has shifted depending on a variety of factors. The weather, rises/falls in cases, and regional policies have all impacted the ways people have responded to the pandemic and their behavior as consumers. This past summer, when people around the world typically take their vacations, was a time of reckoning for many. How would people make their escapes while balancing safety and practicality? Hybrid Theory is here to help travel marketers better understand previous consumer trends and where the industry is going. We are constantly analyzing data from online behavior across 18M websites to determine key travel consumption habits. With these insights, we can help travel marketers convert challenges into opportunities. Key Takeaways 1 2 3 4 Americans and Australians Searches for “hotels” in 58% of travelers around Vacation house rentals appear more interested Great Britain saw a the globe plan to take a worldwide are down only than their counterparts significant peak in late domestic trip (either by 6% year-to-date. around the world to travel summer, while interest plane or car) in the by car instead of plane. from other regions remainder of 2020. remained constrained. Hybrid Theory Research Highlights Road Trip Australians and Americans 350 searched for “Road Trip” this past summer at much higher 300 rates than their counterparts around the world. 250 A possible explanation is that 200 people in countries with large landmasses (like AU and US) 150 might be more interested in traveling by road. -

Nu-Metal As Reflexive Art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Porcello, Niccolo, "Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 580. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFFECTIVE!MASCULINITES!AND!SUBURBAN!IDENTITIES:!! NU2METAL!AS!REFLEXIVE!ART! ! ! ! ! ! Niccolo&Dante&Porcello& April&25,&2016& & & & & & & Senior&Thesis& & Submitted&in&partial&fulfillment&of&the&requirements& for&the&Bachelor&of&Arts&in&Urban&Studies&& & & & & & & & _________________________________________ &&&&&&&&&Adviser,&Leonard&Nevarez& & & & & & & _________________________________________& Adviser,&Justin&Patch& Porcello 1 This thesis is dedicated to my brother, who gave me everything, and also his CD case when he left for college. Porcello 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Click Click Boom ............................................................................................. -

Personal Denial and Social Rejection Reflected in Linkin Park’S Album “Meteora” a Final Project

PERSONAL DENIAL AND SOCIAL REJECTION REFLECTED IN LINKIN PARK’S ALBUM “METEORA” A FINAL PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English By Adi Indra Kurniawan 2250402014 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS SEMARANG STATE UNIVERSITY 2007 PERNYATAAN Nama : ADI INDRA KURNIAWAN NIM : 2250402014 Prodi/ jurusan : Sastra Inggris S1/ Bahasa Inggris Fakultas : Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa skripsi/ tugas akhir/ final project yang berjudul: PERSONAL DENIAL AND SOCIAL REJECTION REFLECTED IN LINKIN PARK’S ALBUM “METEORA” Yang saya tulis dalam rangka memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana ini benar – benar hasil karya saya sendiri, yang saya hasilkan setelah melalui penelitian, pembinbingan, diskusi dan pemaparan/ ujian. Semua kutipan, baik langsung maupun tidak langsung, baik yang diperoleh dari sumber kepustakaan, wahana elektronik maupun sumber lainnya telah disertai keterangan mengenai sumbernya dengan cara sebagaimana yang lazim dalam penulisan karya ilmiah; dengan demikian walaupun tim penguji dan pembimbing penulisan skripsi/ tugas akhir/ final project ini membubuhkan tanda tangan sebagai tanda keabsahanny, seluruh isi karya ilmiah ini tetap menjadi tanggung jawab saya sendiri. Jika di kemudian hari ditemukan ketidakberesan saya bersedia untuk menerima akibatnya. Demikian, untuk dapat dipergunakan sebagaimana mestinya. Semarang, November 2006 Yang membuat pernyataan Adi Indra Kurnaiawan ii PAGE OF APPROVAL This Final Project was approved by the Board of examiners of The Faculty of Language and Arts of Semarang State University on ………………………… The Board of Examiners 1. Chairperson of the Examination Prof. Dr. Rustono, M. Hum NIP. 131281222 2. Secretary of the Examination Drs. Suprapto, M. Hum NIP. -

Linkin Park Hybrid Theory Album Download 320Kbps Free Linkin Park Discography FLAC + CUE

linkin park hybrid theory album download 320kbps free Linkin Park Discography FLAC + CUE. LINKIN PARK DISCOGRAPHY FLAC FREE DOWNLOAD (LOSSLESS) DISCOGRAPHY: Linkin Park FORMAT: FLAC + CUE 16bits (lossless) GENERE: Alternative YEAR: 2000 – 2017 COUNTRY: USA DOWNLOAD: Mega DISC: 10 Studio Albums SOURCE: https://www.discogc.com PASSWORD: www.discogc.com. LINKIN PARK DISCOGRAPHY STUDIO ALBUMS. 01 – Papercut 02 – One Step Closer 03 – With You 04 – Points Of Authority 05 – Crawling 06 – Runaway 07 – By Myself 08 – In The End 09 – A Place For My Head 10 – Forgotten 11 – Cure For The Itch 12 – Pushing Me Away. 01 – Foreword 02 – Don’t Stay 03 – Somewhere I Belong 04 – Lying From You 05 – Hit The Floor 06 – Easier To Run 07 – Faint 08 – Figure.09 09 – Breaking The Habit 10 – From The Inside 11 – Nobody’s Listening 12 – Session 13 – Numb. 01 – Wake 02 – Given Up 03 – Leave Out All The Rest 04 – Bleed It Out 05 – Shadow Of The Day 06 – What I’ve Done 07 – Hands Held High 08 – No More Sorrow 09 – Valentine’s Day 10 – In Between 11 – In Pieces 12 – The Little Things Give You Away 13 – No Roads Left (Bonus) 14 – What I’ve Done (Distorted Remix) 15 – Given Up (Third Encore Session) 01 – The Requiem 02 – The Radiance 03 – Burning In The Skies 04 – Empty Spaces 05 – When They Come For Me 06 – Robot Boy 07 – Jornada Del Muerto 08 – Waiting For The End 09 – Blackout 10 – Wretches And Kings 11 – Wisdom, Justice, And Love 12 – Iridescent 13 – Fallout 14 – The Catalyst 15 – The Messenger. -

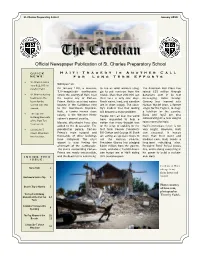

January Issue

St. Charles Preparatory School January 2010 TheThe CarolianCarolian Official Newspaper Publication of St. Charles Preparatory School QUICK Haiti Tragedy Is Another Call NEWS: for Long Term Efforts St. Charles raises Will Ryan ‘10 over $11,000 for relief in Haiti! On January 12th, a massive, to rise as relief workers strug- The American Red Cross has 7.0—magnitude earthquake gle to pull survivors from the raised $25 million through St. Charles hockey struck the country of Haiti, near rubble. More than 200,000 lost donations sent in by text team beats the the capital city of Port-au- their lives in only nine days. messaging. Actor George bears for the Prince. Haiti is an island nation Fresh water, food, and gasoline Clooney has teamed with second time this located in the Caribbean next are in short supply. The coun- Haitian Wyclef Jean, a former season. to the Dominican Republic. try’s leaders fear that looting singer for the Fugees, to stage Haiti, a former French slave will become a major problem. a telethon for the country. The Top Ten colony, is the Western Hemi- People from all over the world Bono and Jay-Z are also Defining Moments sphere’s poorest country. collaborating on a new song to of the Past Ten have responded to help a Massive aftershocks have also nation that many thought was raise money for Haiti. Years are in. added to the devastation. The on the verge of stability for the Haiti’s immediate future is not Living Like T. presidential palace, Port-au- first time. -

In the End (2000) Linkin Park

MUSC-21600: The Art of Rock Music Prof. Freeze In the End (2000) Linkin Park LISTEN FOR • Heavy metal: textures, vocal quality of chorus, imagery (in video) • Rap: turntabilism, vocal delivery in verses • Layered textures CREATION Songwriters Bradford Delson, Chester Bennington, Joseph Hahn, Michael Shinoda, Robert Bourdon Album Hybrid Theory Label Warner Bros. Musicians Chester Bennington (vocals), Rob Bourdon (drums), Brad Delson (guitar, bass), Joseph Hahn (sample keyboard, turntables), Mike Shinoda (rapping) Producer Don Gilmore Recording Soundtrack (New York, NY); 2000; Charts Pop 2 MUSIC Genre Nu metal, rap rock Form Contrasting verse-chorus Key E-flat major Meter 4/4 MUSC-21600 Listening Guide Freeze “In the End” (Linkin Park, 2001) LISTENING GUIDE Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0:00 Introduction (8) • Piano riff with reverb • Scratchy white noise • Sampled beat reminiscent of 80s hip- hop 0:19 Verse 1 (8+4+4) “It starts with one” • Rapping vocal delivery 0:37 • Heavy low end and high bell tones 0.46 reminiscent of gangsta rap texture • Bell tones done resolve, creating tension 0:56 Chorus (8) “I tried so hard” • Melodic resolution creates sense of arrival, completion • Thick, metal guitar chords • Processed vocals, aggressive quality recalls hard rock (had previously been the “sweeter” voice) 1:15 Verse 2 (8+4+4) “One thing, I don’t know why” • 1:32 • Piano riff returns 1:42 • Sustained, high backing vocals 1:51 Chorus (8) “I tried so hard” • As before 2:10 Bridge (8+8) • Based on introductory piano riff; 2:29 personal, almost confessional vocal quality. • Texture of chorus: thick, distorted guitar; aggressive vocal quality (but solo track) 2:48 Chorus (8) “I tried so hard” • Different guitar chords? 3:06 Close • Return of introductory piano riff and scratching. -

Download Minutes to Midnight Full Album Minutes to Midnight

download minutes to midnight full album Minutes to Midnight. Damned if they do, damned if they don't -- that was the conundrum facing Linkin Park when it came time to deliver Minutes to Midnight, their third album. It had been four years since their last, 2003's Meteora, which itself was essentially a continuation of the rap-rock of their 2000 debut, Hybrid Theory, the blockbuster that was one of the biggest rock hits of the new millennium. On that album, Linkin Park sounded tense and nervous, they sounded wiry -- rap-rock without the maliciousness that pulsed through mock-rockers like Limp Bizkit. Linkin Park seemed to come by their alienation honestly, plus they had hooks and a visceral power that connected with millions of listeners, many of whom who were satisfied by the familiarity of Meteora. They may have been able to give their fans more of the same on their sophomore effort, but Linkin Park couldn't do the same thing on their third record: they would seem like one-trick ponies, so they'd be better off to acknowledge their advancing age and try to mature, or broaden their sonic palette. Yet like many other hard rockers, they were the kind of band whose audience either didn't want change or outgrew the group -- and considering that it had been a full seven years between Hybrid Theory and Minutes to Midnight, many fans who were on the verge of getting their driver's license in 2000 were now leaving college and, along with it, adolescent angst. So, Linkin Park decided to embrace the inevitable and jumped headfirst into maturity on Minutes to Midnight, which meant that poor Mike Shinoda was effectively benched, rapping on just two songs. -

Formal Grammar, Usage Probabilities, and Auxiliary Contraction Joan Bresnan

Formal grammar, usage probabilities, and auxiliary contraction Joan Bresnan Language, Volume 97, Number 1, March 2021, pp. 108-150 (Article) Published by Linguistic Society of America DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2021.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/785541 [ Access provided at 19 Apr 2021 00:58 GMT from Stanford Libraries ] FORMAL GRAMMAR, USAGE PROBABILITIES, AND AUXILIARY CONTRACTION Joan Bresnan Stanford University This article uses formal and usage-based data and methods to argue for a hybrid model of En- glish tensed auxiliary contraction combining lexical syntax with a dynamic exemplar lexicon. The hybrid model can explain why the contractions involve lexically specific phonetic fusions that have become morphologized and lexically stored, yet remain syntactically independent, and why the probability of contraction itself is a function of the adjacent cooccurrences of the subject and auxiliary in usage, yet is also subject to the constraints of the grammatical context. Novel evidence includes a corpus study and a formal analysis of a multiword expression of classic usage-based grammar.* Keywords: contraction, clitic, corpus, probability, LFG, exemplar, usage At first sight, formal theories of grammar and usage-based linguistics appear com- pletely opposed in their fundamental assumptions. As Diessel (2007) describes it, formal theories adhere to a rigid division between grammar and language use: grammatical structures are independent of their use; grammar is a closed and stable system and is not affected by pragmatic and psycholinguistic principles involved in language use. Usage- based theories, in contrast, view grammatical structures as emerging from language use and constantly changing through psychological processing.