INSTITUTION EDES PRICE Topic Is Curriculum Development, Centering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy in Statu Nascendi

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2014 Number 32 Living a Philosophy of Early Childhood Education: A Festschrift for Harriet Article 6 Cuffaro October 2014 Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi Jeroen Staring Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Staring, J. (2014). Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi. Occasional Paper Series, 2014 (32). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2014/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi By Jeroen Staring This article explores two themes in the life of Caroline Pratt, founder of the Play School, later the City and Country School. These themes, central to Harriet Cuffaro’s values as a teacher and scholar, are Pratt’s early progressive pedagogy, developed during experimental shopwork between 1901 and 1908; and her theories on play and toys, developed while observing children play with her Do-With Toys and Unit Blocks between 1908 and 1914. Focusing on her early and previously unexplored writings, this article illustrates how Caroline Pratt developed a coherent theory of innovative progressive pedagogy. Figure 1 (left). Original drawing of Do-With doll, by Caroline Pratt. Figure 2 (right): Two wooden, jointed Do-With dolls. (Photo: Jeroen Staring, 2011; Courtesy City and Country School, New York City) 46 | Occasional Paper Series 32 bankstreet.edu/ops Caroline Pratt’s Education In 1884, Caroline Louise Pratt, age 17, had her first teaching experience at the summer session of a school near her hometown, Fayetteville, New York. -

The Technological Imaginary of Imperial Japan, 1931-1945

THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Stephen Moore August 2006 © 2006 Aaron Stephen Moore THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 Aaron Stephen Moore, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 “Technology” has often served as a signifier of development, progress, and innovation in the narrative of Japan’s transformation into an economic superpower. Few histories, however, treat technology as a system of power and mobilization. This dissertation examines an important shift in the discourse of technology in wartime Japan (1931-1945), a period usually viewed as anti-modern and anachronistic. I analyze how technology meant more than advanced machinery and infrastructure but included a subjective, ethical, and visionary element as well. For many elites, technology embodied certain ways of creative thinking, acting or being, as well as values of rationality, cooperation, and efficiency or visions of a society without ethnic or class conflict. By examining the thought and activities of the bureaucrat, Môri Hideoto, and the critic, Aikawa Haruki, I demonstrate that technology signified a wider system of social, cultural, and political mechanisms that incorporated the practical-political energies of the people for the construction of a “New Order in East Asia.” Therefore, my dissertation is more broadly about how power operated ideologically under Japanese fascism in ways other than outright violence and repression that resonate with post-war “democratic” Japan and many modern capitalist societies as well. This more subjective, immaterial sense of technology revealed a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of technology. -

Philosophy of Social Efficiency. John Deweys Complex Analyses of the Values of Science, Technology, and Democracy for Education in a Technological World Are Examined

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 051 002 08 SO 000 860 AUTHOR Wirth, Arthur G. TITLE The Vocational-Liberal Studies Controversy Between John Dewey and Others (1900-1917). Final Report. INSTITUTION Washington Univ., St. Louis, Mo. Graduate Inst. of Education. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. PUB DATE Sep 70 GRANT OEG -0 -8- 070305 -3662 (085) NOTE 349p.; Report will be published as Education in the Technological Society: The Vocational-Liberal Studies Controversy (1900-1917), International Textbook Co., 1972 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS Comprehensive High Schools, Democratic Values, *Educatfonal Change, *Educational History, *Educational Philosophy, Educational Policy, Educational Sociology, General Education, *Industrialization, Occupational Guidance, Political Influences, Public Education, School Community Relationship, Social Change, Social Values, Socioeconomic influences, *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Dewey (John) ABSTRACT The present study looks at an example of institutional change directly resulting from the industrialization process --the industrial or vocational education movement. The thesis of this study is that an understanding of the debate over how schools should adapt to industrialization will reveal the nature of basic value choices which the American people were forced to face under the pressures of adjusting to technology. Part I examines some of the origins of educational changes related to the industrialization. Next the responses of selected interest groups are considered: business, as represented by the National Association of Manufacturers; the American Federation of Labor; liberal urban reform forces of the progressive era; and, the formation of typical progressive pressure group--the National Society for the Promotion of Industrial Education (NSPIE), which worked to promote school reform programs at state and national levels. -

Progressive Education

PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION Lessons fronn the Past and Present Susan F. Semel, Alan R. Sadovnik, and Ryan W. Coughlan Progressive education is one of the most enduring educational reform move ments in this country, with a lifespan of over one hundred years. Although as noted earlier, it waxes and wanes in popularity, many of its practices now appear so regularly in both private and public schools as to have become almost mainstream. But from the schools that were the pioneers, what useful ■ lessons can we learn? The histories of the early progressive schools profiled in ■part 1 illustrate what happened to some of the progressive schools founded in I jhe first part of the twentieth century. But even now, they serve as important reminders for educators concerned with the competing issues of stability and change in schools with particular progressive philosophies—reminders, spe cifically, of the complex nature of school reform.' As we have seen in these histories, balancing the original intentions of progressive founders with the known demands upon practitioners has been the challenge some of the schools have met successfully and others have not. As contemporary American educators consider the school choice movement, the burgeoning expansion of charter schools, and the growing focus on stan- dards-based testing and accountability measures, they would do well to look back for guidance at some of the original schools representative of the “new education.” Particularly instructive. The Dalton School and The City and 374 SUSAN F. SEMEL ET AL. Country School are both urban independent schools that have enjoyed strong and enduring leaders, well-articulated philosophies and accompanying ped agogic practice, and a neighborhood to supply its clientele. -

Early Steps Celebration 30Th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 the University Club New York, NY

Benefit Early Steps Celebration 30th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 The University Club New York, NY Early Steps 540 East 76th Street • New York, NY 10021 www.earlysteps.org • 212.288.9684 Horace Mann School and all of our Early Steps students and families, past and present, join in celebrating Early Steps’ 30 Years as A Voice for Diversity in NYC Independent Schools Letter from our Director Dear Friends, For nearly three decades, it has been my joy and re- sponsibility to guide the parents of children of color through the process of applying to New York City in- dependent schools for kindergarten and first grade, helping them to realize their hopes and dreams for their children. While over 3,500 students of color entered school with the guidance of Early Steps, it is humbling to know that the impact has been so much greater. We hear time and © 2012 Victoria Jackson Photography again how families, schools and lives have been trans- formed as a result of the doors of opportunity that were opened with the help of Early Steps. Doors where academic excellence is the norm and children learn and play with others whose life’s experiences are not the same as theirs, benefitting all children. We are proud of our 30-year partnership with now over 50 New York City independent schools who nurture, educate and challenge our children to be the best that they can be. They couldn’t be in better hands! Tonight we honor four Early Steps alumni. These accomplished young adults all benefited from the wisdom of their parents who knew the importance of providing their children with the best possible education beginning in Kindergarten. -

293145618.Pdf

Leaders in Educational Research LEADERS IN EDUCATIONAL STUDIES Volume 7 Series Editor: Leonard J. Waks Temple University, Philadelphia, USA Scope: The aim of the Leaders in Educational Studies Series is to document the rise of scholarship and university teaching in educational studies in the years after 1960. This half-century has been a period of astonishing growth and accomplishment. The volumes in the series document this development of educational studies as seen through the eyes of its leading practitioners. A few words about the build up to this period are in order. Before the mid-twentieth century school teaching, especially at the primary level, was as much a trade as a profession. Schoolteachers were trained primarily in normal schools or teachers colleges, only rarely in universities. But in the 1940s American normal schools were converted into teachers colleges, and in the 1960s these were converted into state universities. At the same time school teaching was being transformed into an all-graduate profession in both the United Kingdom and Canada. For the first time, school teachers required a proper university education. Something had to be done, then, about what was widely regarded as the deplorable state of educational scholarship. James Conant, in his final years as president at Harvard in the early 1950s, envisioned a new kind of university-based school of education, drawing scholars from mainstream academic disciplines such as history, sociology psychology and philosophy, to teach prospective teachers, conduct educational research, and train future educational scholars. One of the first two professors hired to fulfil this vision was Israel Scheffler, a young philosopher of science and language who had earned a Ph.D. -

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

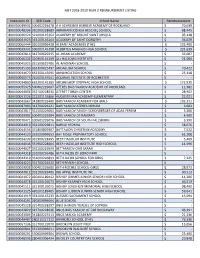

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

A Theory-Based Approach to Market Transformation

A Theory-based Approach to Market Transformation Carl Blurn.rtein, University of Cal#ornia En!ergy Institute, Berkeley, CA Seymour Goldstone, California Energy Commission, Sacramento, CA Loren Lutzenhiser, Washington State University, Pullman, WA ABSTRACT Market transformation (MT) programs face numerous challenges in identifying targets, undemanding markets, and intervening effective y in them. Traditional energy efficiency progmm approaches generally lack the tools necessary to meet those challenges. New energy market realities and new public purposes roles for government that emphasize market connectivity will require more sophisticated forms of MT that focus on murkets rather than end-users. One such approach, being developed by the California Energy Commission, stresses the importance of theory-based MT, with tight linkages between existing theory, program design, empirical testing of crucial assumptions, evaluation, and theory development. Feedback and itetative learning are involved at all stages. Because a clear understanding of market dynamics is crucial to this approach, multidisciplinary research plays a key role. Introduction In this paper we sketch an approach to market transformation (MT) appropriate to the new realities of the 21st Century. We first discuss sources of MT thinking and assess the usefulness to ~ interventions of energy efficiency strategies and research agendas inherited from the period of efficiency resource acquisition. Our main point is that, as a result of changes in energy efficiency programs, what we need to know to conduct successfid programs has also changed. This provides the context for our description of a systematic strategy for MT being developed by the California Energy Commission (CEC). This strategy has the advantage of recognizing the need for new knowledge, careful program design, pilot testing, and real-time evaluation with feedback loops. -

Eugenics and Education: Implications of Ideology, Memory, and History for Education in the United States

Abstract WINFIELD, ANN GIBSON. Eugenics and Education – Implications of Ideology, Memory, and History for Education in the United States. (under the direction of Anna Victoria Wilson) Eugenics has been variously described "as an ideal, as a doctrine, as a science (applied human genetics), as a set of practices (ranging from birth control to euthanasia), and as a social movement" (Paul 1998 p. 95). "Race suicide" (Roosevelt 1905) and the ensuing national phobia regarding the "children of worm eaten stock" (Bobbitt 1909) prefaced an era of eugenic ideology whose influence on education has been largely ignored until recently. Using the concept of collective memory, I examine the eugenics movement, its progressive context, and its influence on the aims, policy and practice of education. Specifically, this study examines the ideology of eugenics as a specific category and set of distinctions, and the role of collective memory in providing the mechanism whereby eugenic ideology may shape and fashion interpretation and action in current educational practice. The formation of education as a distinct academic discipline, the eugenics movement, and the Progressive era coalesced during the first decades of the twentieth century to form what has turned out to be a lasting alliance. This alliance has had a profound impact on public perception of the role of schools, how students are classified and sorted, degrees and definitions of intelligence, attitudes and beliefs surrounding multiculturalism and a host of heretofore unexplored ramifications. My research is primarily historical and theoretical and uses those material and media cultural artifacts generated by the eugenics movement to explore the relationship between eugenic ideology and the institution of education. -

Essay Reviews

Essay Reviews Journeys of Expansion and Synopsis: Tensions in Books That Shaped Curriculum Inquiry, 1968–Present WILLIAM H. SCHUBERT University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL, USAcuri_468 17..94 Abstract In honor of the 40th volume of Curriculum Inquiry, I begin by claiming that pursuit of questions about what is worthwhile, why, and for whose benefit is a (perhaps the) central consideration of curriculum inquiry. Drawing autobiographically from my experience as an educator during the past 40 years, I sketch reflections on curricu- lum books published during that time span. I situate my comments within both the historical backdrop that preceded the beginning of Curriculum Inquiry and the emergence of new curricular languages or paradigms during the late 1960s and early 1970s. I suggest that two orientations of curriculum books have provided a lively tension in curriculum literature—one expansive and the other synoptic—while cautiously wondering if both may have evolved from different dimensions of John Dewey’s work. I speculate about the place of expansion and synopsis in several categories of curriculum literature: historical and philosophical; policy, profes- sional, and popular; aesthetic and artistic; practical and narrative; critical; inner and contextual; and indigenous and global. Finally, I reconsider expansive and synoptic tendencies in light of compendia, heuristics, and venues that portray evolving curriculum understandings without losing the purport of myriad expansions of the literature. The curriculum field has a complex -

Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING the POSSIBLE! Progressivenational Education Conference Network New York City October 8-10, 2015

1 Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING THE POSSIBLE! Progressive Education Network National Conference New York City PEN_Conference_2015.indd 1 October 8-10, 2015 9/29/15 2:25 PM 2 Mission and History of the Progressive Education Network “The Progressive Education Network exists to herald and promote the vision of progressive education on a national basis, while providing opportunities for educators to connect, support, and learn from one another.” In 2004 and 2005, The School in Rose Valley, PA, celebrated its seventy- fifth anniversary by hosting a two-part national conference, Progressive Education in the 21st Century. Near the end of the conference, a group of seven educators from public and private schools around the country rallied to a call-to-action to revive the Network of Progressive Educators, which had been inactive since the early 1990s. Inspired by the progressive tenets of the conference, the group shared a grand collective mission: to establish a national group to rise up, protect, clarify, and celebrate the principles of progressive education and to fashion a revitalized national educational vision. This group, “The PEN Seven” (Maureen Cheever, Katy Dalgleish, Tom Little, Kate (McLellan) Blaker, John Pecore, Lisa Shapiro, and Terry Strand) hosted the organization’s first national conference in San Francisco in 2007. As a result of the committee’s efforts, the Progressive Education Network (PEN) was formed and in 2009 was incorporated as a 501 (c) 3 charitable, non-profit organization. Biannual conferences, supported by PEN and produced by various committees, followed in DC, Chicago, and LA, with attendance growing from 250 to 950. -

Implications for Democratic Education

The End of Efficiency: Implications for Democratic Education FRANCINE MENASHY Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto ABSTRACT: This paper provides an examination of the concept of efficiency and its application to current educational initiatives and reforms. It is shown that several movements in education are primarily based on a narrow conception of efficiency, giving rise to serious ethical concerns. Beginning with an examination of the term efficiency and common misconceptions of its meaning, manifestations of the efficiency movement in education are then described, followed by their ethical implications in terms of democratic education and equity issues. It will be concluded that the problematic consequences of efficiency initiatives in schools are mainly due to the application of an overly narrow conception of efficiency. RESUME: lei, le concept d la competence et de sa pratique dans les reformes et les initiatives actuelles de l'enseignement, sont analyses. 11 y est demontre que plusieurs mouvements dans l' enseignement s'appuient d' abord sur une conception limitee de la competence soulevant ainsi, des problemes importants d'ordre ethique. Le papier commence par une analyse du mot "competence" et des conceptions erronees de sa signification, ensuite par la description des manifestations du mouvement de competence dans l'enseignement, puis par leurs mises en action ethiques en termes d'enseignement democratiques et de questions d'equite. On en conclura queles consequences problematiques des initiatives de competence dans les ecoles sont principalement dues a la mise en pratique d'une conception de la competence qui est plus que limitee. The label efficient is rarely given as a pejorative.