The Villiers Story Page 1 of 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South of England Classic Motorcycle Show: Sunday 23Rd October 2016 Page 1 of 25 South of England Classic Motorcycle Show: Draft Programme: Sunday 23Rd October 2016

South of England Classic Motorcycle Show: Sunday 23rd October 2016 Page 1 of 25 South of England Classic Motorcycle Show: Draft Programme: Sunday 23rd October 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________________Year Make Model Club cc 1913 Zenith Gradua 90 Bore 996 Classes Entered:Pre 1950 VMCC (Surrey & Sussex) Bike Details: Built at Weybridge, Surrey, to the special order of Hal Hill, it lived on Monument Hill, Weybridge until 1953 when it was obtained by the present owner. Used by Hal Hill at Brooklands and many long-distance rallies before & after the First World War and last used by him in 1925. Fitted with the Gradua Gear, designed by Freddie Barnes in 1908 and fitted by Zenith until 1925. Zenith were barred from competing in the same classes as machines without variable gears, hence from 1910 the Zenith Trade Mark included the word BARRED. Capable of about 70 mph on the track, it's fitted with the JAP sidevalve engine, with 90mm bore x 77.5 stroke. It also has the large belt pulleys giving a variation from 3 to 1 in top gear, down to 6 to 1 in low gear. Rebuilt in 1964 and used by the current owner in VMCC events. _________________________________________________________________________________________ 1914 Rover Sturmey Archer 3 ½ Classes Entered:Pre 1950 Sunbeam MCC Bike Details: Found languishing in a garage, last used in 1972, as witnessed by an old tax disc. Not a barn find but a garage find. _________________________________________________________________________________________ 1914 Triumph F 3½ Classes Entered:Pre 1950 Sunbeam MCC Bike Details: TT Racer Fixed engine model F. The type F was supplied with a 3½ HP engine as standard (85 x 88mm = 499cc) to comply with TT regulations. -

Motorcycles - Part 5 - Bob Thomas Page 39 Past Problems

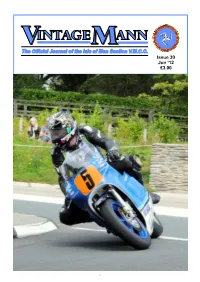

Page 1 Paradise & Gell has been located on Michael Street in Peel since 1974. Here you will find a wide range of furnishings to enhance any living space. Whether you are looking for something contemporary or a more traditional piece, then look no further than Paradise & Gell. Page 2 Contents Page 2 Chairman's Chat Page 3 Secretary's Notes Page 5 Yellow Belly Notes - "If you go down to the woods today.." Page 9 The Vincent is Dead! - Long live the Vincent Page 14 The Stillborn JAWA Boxer Page 20 Book Review - The Rugged Road Page 23 Forthcoming Events Page 24 VMCC Trial Results Page 27 Ray Amm - Rider Profile No. 16 Page 28 Sons of Thunder - Pt 4 - Allan Jermieson Page 34 Motorcycles - Part 5 - Bob Thomas Page 39 Past Problems Editor: Job Grimshaw Sub Editor: Harley Richards Cover Pic - John Barton on Rupert Murden’s GSXR 750 at Governors Bridge en route to second place in the Classic Superbike Manx Grand Prix. They purchased the bike on eBay! Page 1 Chairman’s chat Dear Members, I hope that you are getting in some riding despite the weather. Its got to warm up soon surely? The TT is now upon us and I am sure that you will wish Brian Ward and his team every success with the TT rally. Hopefully you have chosen to enter in time, as all events take a great deal of pre-planning and commitment, and it is always gratifying to see some returns for your efforts. At this time the Manx Grand Prix is under scrutiny and discussion, the out- come will inevitably affect our Rally and the Jurby event. -

5. Men of Substance – 1

5. Men of Substance – 1 When we are young and in the prime of our youth our lives pass so fast that events come and go quickly like today’s daily News. No sooner one event passes, another leaps up to replace it. Only the more dramatic or the humorous for the most part will stick with us. I recently discovered and read an old magazine article written in March 1992 to commemorate the anniversary of the tragic loss of Mike Hailwood. It triggered in me an old memory that I thought I had completely forgotten with the passage of time. Back around 1964/5 I was a member of a UK motorcycle club called The Southend & District MCC. Although I never met them, Bill Ivy and Dave Bickers were also registered members of the same club in compliance with an official UK ACU racing license ruling at that time. The ACU (Auto Cycle Union) was similar to the US. AMA (American Motorcycle Association) in governing all forms of motorcycle sport. We were treated to many a fascinating Club Talk by some quite prominent people of the day such as Charles Mortimer Sr. and Wal Phillips, (a veteran cinder-track speedway rider who was one of the first to develop aftermarket fuel injectors for motorcycles in the UK.), to name but a couple. An Avon Tire representative once came and gave a full presentation on the then newly developing technology of 'Avon Cling' High Hysteresis Tire Compounds. Bert Greeves, founder and owner of Greeves Motorcycles, was also a highly prominent figure along with his long-time friend and business associate, Derry Preston-Cobb, who ran the Greeves subsidiary of Invacar, an independent invalid vehicle factory located next door to the main Greeves factory on One Tree Hill, in Thundersley, Essex. -

British Two Stroke Club of Australia News Letter #138 October 2014

Incorporated Victoria 1996 Number A0031204N Oct 2014 Newsletter No 138 Articles for Plug Whiskers to be in three weeks prior to the next Meeting please! BTSCA Inc. Committee 2013-2014 Next Meeting President Neil Jenkins 03 5447 9071 Blackwood 18/19th Sept 2014, at Vice President Ian Barber 03 9758 0440 Doubleday’s cottage. Secretary Andrew O’Sullivan 03 5122 2337 Treasurer Ross Jenkins 03 9029 2484 7th Dec 2014 – Red Plate Café – Yea. Email: [email protected] Membership Sec. Ross Jenkins 03 9029 2484 Red Plate Events Club Captain Greg Doubleday 03 5447 8156 Public Officer Andrew O’Sullivan 03 5122 2337 Brian Beere Run, 1st Sunday of the month, Red Plate Register Andrew O’Sullivan 03 5122 2337 meet at Baxter Tavern 9.00am, contact Newsletter Editor Arthur Freeman 03 5977 3280 John & Deb Allen (03 9776 8464). P/W Labels Ross Jenkins 03 9029 2484 Permit Renewals Neil Jenkins 03 5447 9071 Bendigo Section ride, 2nd Sunday of the Alan Scoble 03 5967 3518 month, meet at Kangaroo Flat, contact Neil Andrew O’Sullivan 03 5122 2337 Jenkins (03 5447 9071). Committee Alan Scoble 03 5967 3518 Anne Scoble 03 5967 3518 Any other Rallies/Red Plate Events, please Carl Hopkins 03 9809 2495 inform Editor (well in advance). Club Marque Specialists NewsLetter Editor address details: Please post neatly handwritten, typed or BSA Bantam Tom Abbey 03 9786 7840 computer files to: BSA Bantam D5-D13 Neil Jenkins 03 5447 9071 Arthur Freeman, 8 Delepan Drive, Tyabb, Flandria Carl Hopkins 03 9809 2495 Vic 3913 Email - Francis Barnett/Jawa Bill Barfield 03 5721 4832 [email protected] Greeves Peter Growse 03 9755 3310 James Ken Aitken 03 5786 1658 Puch Greg Doubleday 03 5447 3518 Villiers Post War Alan Scoble 03 5967 3518 Villiers Pre-war Bob McGrath 03 9898 7967 General Two Stroke Malcolm Day 03 9435 7824 Bits & Pieces BTSCA Inc is a member of the Federation of Veteran, Vintage and Classic Vehicles Clubs of Victoria. -

A New Beginning..?

OWNERS CLUB Peashooter SURREY BRANCH The Newsletter of the Norton Owners Club - Surrey Branch www.surreynoc.org.uk Issue 7 - November 2009 Mike doing his presidential duty at this A new year's International Rally in Austria A Presidential visit! Mike Jackson, Norton's former Sales Director , one-time owner beginning..? of Andover Norton and National President of the NOC has agreed to talk to the Branch at the Club meeting on 30th A number of Branch Members have made contact with November. Peashooter, concerned that Peter & Colin (the current Mike has competed in trials and motocross events at the Chairman & Secretary) were leaving and does this mean highest level in UK, Europe and USA. He began racing in 1954, that the club was finishing? "I hope not", said Peter, "But it's riding on Francis Barnett, James, Greeves and AJS, winning pretty vital that we find some of our 60 members who are numerous events. During this time he worked in sales for willing to put themselves forward at the AGM to be held on Greeves and later AJS. When he was appointed General Sales Monday 26th!". Manager for Norton Villiers Corp in 1970, he moved to the US, and raced AJS in West Coast Desert events. He enjoyed some top placings in the prestigious Barstow To Vegas Hare and "Both of us would have liked to carry on but as we're both Hounds and the Elsinore Grand Prix. moving away from the area during the next few weeks, it's time for a new Committee team to take the Branch Mike 's career with Norton Villiers continued - he became Sales forward", said Peter. -

The Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited (BSA) Was A

Norton Villiers Triumph Norton Villiers/BSA factory in Small Heath in its heyday _____________________________________________________________________ Norton Villiers Triumph was a British motorcycle manufacturer, formed by the British Government to continue the UK motorcycling industry, but the company eventually failed. Triumph had been owned by the BSA Group since 1951, but by 1972 the merged BSA-Triumph group was in serious financial trouble. British Government policy at the time was to save strategic industries with tax payers' money, and as BSA-Triumph had won the Queen's Awards for Exports a few years earlier, the industry was deemed 'strategic' enough for financial support. The Conservative Government under Ted Heath concluded to bail out the company, provided that to compete with the Japanese it merged with financially troubled Norton Villiers (the remains of Associated Motor Cycles, which had gone bust in 1966), a subsidiary of British engineering conglomerate Manganese Bronze. The merged company was created in 1973, with Manganese Bronze exchanging the motorcycle parts of Norton Villiers in exchange for the non-motorcycling bits of the BSA Group—mainly Carbodies, the builder of the Austin FX4 London taxi: the classic "black cab." As BSA was both a failed company and a solely British-known brand (the company's products had always been most successfully marketed in North America under the Triumph brand), the new conglomerate was called Norton Villiers Triumph—being effectively the consolidation of the entire once-dominant British motorcycle industry. NVT inherited four motorcycle factories—Small Heath (ex-BSA); Andover and Wolverhampton (Norton); and Meriden (Triumph). Meriden was the most modern of the four. -

The Oz Vincent Review Edition #61, April 2019

The Oz Vincent Review Edition #61, April 2019 The Oz Vincent Review is an independent, non-profit, e-Zine about the classic British motorcycling scene with a focus all things Vincent. OVR, distributed free of charge to its readers, may be contacted by email at [email protected] OVR congratulates Vincent Riders Victoria (VRV) on becoming the most recent fully recognised Local Section of the international Vincent H.R.D. Owners Club in Australia. More information about Vincent Riders Victoria, including Membership information, is available on the VRV web site https://secvrv.wixsite.com/vincent also reachable via the VOC’s own web site. Disclaimer: The editor does not necessarily agree with or endorse any of the opinions expressed in, nor the accuracy of content, in published articles or endorse products or services no matter how or where mentioned; likewise hints, tips or modifications must be confirmed with a competent party before implementation. The Oz Vincent Review is an independent, non-profit, electronically distributed magazine about the classic British motorcycling scene with a focus all things Vincent. OVR, distributed free of charge to its readers, may be contacted by email at [email protected] Welcome Welcome to the latest edition in our 6th year of publication! It also marks a milestone in the Australian Vincent community and that is the recognition of Vincent Riders Victoria as a fully recognised Local Section of the international Vincent H.R.D. Owners Club. If you have received this copy of OVR indirectly from another reader you can easily have your very own future editions delivered directly to your personal email inbox; simply click on this link to register for your free subscription. -

Motorcycles and Related Spares & Memorabilia

The Autumn Stafford Sale The Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Show, Stafford | 13 & 14 October 2018 The Autumn Stafford Sale Important Pioneer, Vintage, Classic & Collectors’ Motorcycles and Related Spares & Memorabilia The 25th Carole Nash Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Show Sandylands Centre, Staffordshire County Showground | Saturday 13 & Sunday 14 October 2018 VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Saturday 13 October Monday to Friday 8:30am - 6pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 James Stensel +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 9am to 5pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 8963 2818 [email protected] +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax Please see page 2 for bidder Sunday 14 October To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] from 9am information including after-sale www.bonhams.com collection and shipment Bill To SALE TIMES LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS +44 (0) 20 8963 2822 Please see back of catalogue Saturday 13 October AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax for important notice to bidders Spares & Memorabilia Please email [email protected] [email protected] (Lots 1 - 196) 12 noon with “Live bidding” in the subject line 48 hours before the auction Ben Walker IMPORTANT INFORMATION Followed by The Reed to register for this service +44 (0) 20 8963 2819 The United States Government Collection of Motorcycles +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax has banned the import of ivory (Lots 201 - 242) 3pm Please note that bids should be [email protected] into the USA. Lots containing submitted no later than 4pm on ivory are indicated by the Sunday 14 October Friday 12 October. -

Second World War Relative Decline of Uk Manufacturing 1945-1975, Viewed Through the Lens of the Birmingham Small Arms Company Ltd

AN EXAMINATION OF THE POST- SECOND WORLD WAR RELATIVE DECLINE OF UK MANUFACTURING 1945-1975, VIEWED THROUGH THE LENS OF THE BIRMINGHAM SMALL ARMS COMPANY LTD by JOE HEATON Volume 1: Text A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Lifelong Learning The University of Birmingham July 2007 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This is a study of the decline and collapse, in 1973, of the Birmingham Small Arms Company Ltd, primarily a motorcycle manufacturing company and pre-WW2 world market-leader. The study also integrates and extends several earlier investigations into the collapse that concentrated on events in the Motorcycle Division, rather than on the BSA Group, its directors and its overall strategy. The collapse of BSA was due to failures of strategy, direction and management by directors, who were not up to running one of Britain’s major industrial companies after it was exposed to global competition. While the charge, by Boston Consulting and others, that the directors sacrificed growth for short term profits was not proven, their failure to recognise the importance of motorcycle market share and their policy of segment retreat in response to Japanese competition, played a large part in the decline of the company. -

BRITISH NEW YEAR FINAL.Xlsx

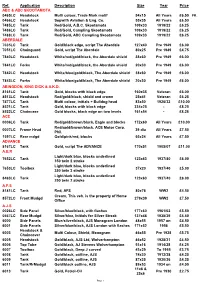

Ref. Application Description Size Year Price ABC & ABC SKOOTAMOTA 0465LC Headstock Multi colour, Trade Mark motif 54x15 All Years £6.50 PR 0466LC Headstock Sopwith Aviation & Eng. Co. 55x35 All Years £6.50 7485LC Tank Red/Gold, A.B.C. Skootamota 109x33 1919/22 £6.25 7486LC Tank Red/Gold, Campling Skootamota 109x33 1919/22 £6.25 7488LC Tank Red/Gold, ABC Campling Skootamota 109x33 1919/22 £6.25 ABERDALE 7035LC Tank Gold/black edge, script The Aberdale 127x40 Pre 1949 £6.00 7051LC Chainguard Gold, script The Aberdale 80x25 Pre 1949 £4.75 7840LC Headstock White/red/gold/black, the Aberdale shield 38x60 Pre 1949 £6.00 7841LC Forks White/red/gold/black, the Aberdale shield 20x30 Pre 1949 £6.00 7842LC Headstock White/blue/gold/black, The Aberdale shield 38x60 Pre 1949 £6.00 7843LC Forks White/blue/gold/black, The Aberdale shield 20x30 Pre 1949 £6.00 ABINGDON, KING DICK & A.K.D. 8161LC Tank Gold, blocks with black edge 160x35 Veteran £6.00 8513LC Headstock Red/gold/black, shield and crown 25x41 Veteran £6.25 7477LC Tank Multi colour, initials + Bulldog head 83x50 1926/32 £10.00 8521LC Tank Gold, blocks with black edge 334x25 - £8.25 8522LC Chaincase Gold blocks, black edge on two levels 161x54 - £8.25 ACE 0006LC Tank Red/gold/brown/black, Eagle and blocks 172x60 All Years £10.00 Red/gold/brown/black, ACE Motor Corp. 0007LC Frame Head 39 dia All Years £7.50 Phil. 1597LC Rear mdgd Gold/pink/red, blocks 65x24 All Years £7.50 ADVANCE 8167LC Tank Gold, script The ADVANCE 170x51 1905/07 £11.00 A.E.R Light/dark blue, blocks underlined 7652LC Tank 123x63 1937/40 £6.00 350 twin 2 stroke Light/dark blue, blocks underlined 7653LC Toolbox 37x20 1937/40 £5.00 350 twin 2 stroke Light/dark blue, blocks underlined 8463LC Tank 123x63 1937/40 £6.00 250 twin 2 stroke A.F.S 8181LCTank Red, AFS 80x76 WW2 £4.50 Cream, This veh. -

• Motorcycle Identification

• • I • MOTORCYCLE IDENTIFICATION A GUIDE TO lHE IDENTIFICATION OF ALL MAKES AND MODELS OF MDTDRCYCL~S, INCLUDING OFF ROAO MACHINES ANO MOPEOS .( • , , BY • LEE 5 . COLE 515.00 COPYRIGHT 1986 BY LEE S. COLE A LEE BOOK PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO REPRODUCE THIS BOOK, OR ANY PART THEREOF, IN ANY FORM. ISBN ' 0-939818-11-6 CONTENTS Motorcycle Identification Chart with Key. • • . • . i , ii,iii Moped Identification Chart . .. iv A Brief History of the Motorcycle . 1 Investigation of Motorcycle Thefts . .. • . •.• ..... 3 Motorcycle Records . • • . • . • . 6 VIN Systems .10 AJS . .15 ARIEL .15 BMW • .16 BSA . .19 BENELLI .21 BRIDGESTONE .22 BULTACO .23 CAGIVA .27 CAN--AM .28 CAPRIOLA • • . • . • . • . 30 DUCAT! .31 FANTIC .32 GREEVES .33 GUAZZONE . .•. • •....•.....•..•... 34 HARLEY-DAVIDSON ......•.. • . •• . •• . • ..•.... 35 HODAKA . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • . 52 HONDA . .54 HUSQVARNA . • . • . • . • . • . .87 INDIAN . • . • . • . • . • . • .. .88 JAWA/CZ ..... • .. • ....... • .. • .. • ..•... 90 KAWASAKI . • . • . • . • . • . • . 91 LAVERDA . lOS MAICO .. 106 MATCHLESS 107 CONTENTS - Cont'd. MONTE SA •••••••••••••••••• 108 MOTO BETA (MB) 10' MOTO GUZZI llO MZ •• ll4 NORTON llS OSSA. ll6 PENTON (KTM) ll8 RICI<MAN ........... • . " • .. • .. • . • ... .. 119 ROYAL ENFIELD . • . • . • . • . .120 SUZUKI ......... • .. • .. • . • ..... • .... 121 TRIUMPH. .130 VELOCETTE . • • . • . • . • • • • . • . • • . • . .133 VESPA . • . • . • . • • . • • . • • • • . • . 134 YAMAIIA 136 YANKEE . • . • . • . • . • • • • • . • • . 159 These charts show the approximate location of engine and frame numbers for all motorcycles listed in this book and for mopeds. If you should encounter a vehicle not listed in this publication, it is suggested that you check all the points shown here. Chances are very good you will find the numbers you are searching for. i 1. Headstock. 2. Left side of crankcase below cylinder. 3. Top of crankcase behind cylinder. -

The Herald Volume 27, Issue 1I April 2010 the Long Way Around by Virgil Foreman

San Diego Antique Motorcycle Club The Herald Volume 27, Issue 1I April 2010 The Long Way Around by Virgil Foreman You know how the night before a big trip you don‘t sleep well because you‘re thinking about did I pack everything? Did I tighten that valve stem cap after I checked the air pressure in my tires? No, not this time. I was dead asleep as soon as my head hit the pillow. However, I was awake before the 4:30 a.m. alarm disturbed the morning silence. This trip had been in various stages of planning for 39 years. My best friend and I had talked about riding our mo- torcycles back to Curlew, WA where we met in 1970. We were riding buddies for 25 years before he passed away about 10 years ago. So this trip was for him and a way for me to say good-bye. My plan was to banzai up 5 to Sacramento; overnight there with the family, and then a 580 mile trip to Portland and spend a couple of days with my daughter. Then on to Curlew, WA, which is about 180 miles north of Spokane and only 5 miles from the Canadian border, then a leisurely trip southward towards home on roads forgotten. I had my hand on the off button within seconds after the alarm sounded. I dressed in my riding gear as the coffee cooked. The bike was packed the night before and pointed towards the garage door waiting to be brought to life Continued on page 3 SDAMC Officers Monthly Meetings President: Are held at: Virgil Foreman 858-279-7117 [email protected] Giovanni’s Restaurant Vice President: 9353 Clairemont Mesa Blvd., San Diego Randy Gannon 858-270-5201 (the corner of Clairemont Mesa Blvd and Ruffin Rd.) [email protected] Secretary: On Gordon Clark Sr.