Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

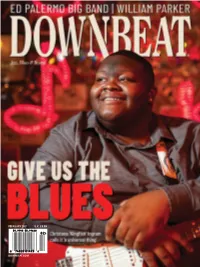

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

September-October 2017 September-October Tyle

www.lowrey.com Wood Dale, IL 60191 Wood EZ Play Song Book Special Offers 989 AEC Drive Welcome Back! LIFE Lowrey Since L.I.F.E. has been on summer vacation, we’d like September Carole King to take this time to say hello to everyone with our “Back E-Z Play Today - Vol. 133 to Lowrey” L.I.F.E.Style Edition. Over the summer, 16 smash hits: Beautiful • Chains • Home Lowrey headquarters in Wood Dale Illinois played host to Again • I Feel the Earth Move • It’s Too Late • The Loco-Motion • (You Make Me L.I.F.E. members, students, and dealers in different events tyle Feel Like) A Natural Woman • So Far and functions. Away • Sweet Seasons • Tapestry • Up on Lacefield Music, from St. Charles and St. Louis Mis- the Roof • Where You Lead • Will You souri, visited early this summer with fifty guests! Lacefield 2017 September-October Love Me Tomorrow • You’ve Got a Friend L.I.F.E. members and students began their trip with a S • and more. quick tour of the Lowrey facility, seeing firsthand the ins Regular Price $9.99 and outs of the Lowrey headquarters. Afterwards, they Use L.I.F.E. discount code: LL09 Hal Leonard Book #: 00100306 were treated to a concert by Bil Curry and Jim Wieda, where they received a special showing and musical demon- October Walk The Line stration of the Lowrey Rialto. Lacefield staff and students E-Z Play Today had an enjoyable day in Wood Dale Illinois immersed in Channel: Youtube Check out the Lowrey Vol. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

The Thrill and the Truth ❏ Aretha Franklin Dies at 76 After Unchallenged Reign As Greatest Vocalist of Her Time

FRIDAY,AUG. 17, 2018 Inside: 75¢ GOP divided over Space Force. — Page 6A Vol. 90 ◆ No. 119 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Los Angeles Times: Lawrence K. Ho Aretha Franklin in concert at the Microsoft Theatre in Los Angeles on Aug. 2, 2015. The thrill and the truth ❏ Aretha Franklin dies at 76 after unchallenged reign as greatest vocalist of her time. Detroit Free warning to “Think.” By Hillel Italie Press: THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Richard Lee Acknowledging the obvious, Rolling Stone ranked her first on NEW YORK — The clarity and James its list of the top 100 singers. the command. The daring and the Brown, Franklin was also named one of discipline. The thrill of her voice right, per- the 20 most important entertainers and the truth of her emotions. forms with of the 20th century by Time mag- Like the best actors and poets, Aretha azine, which celebrated her nothing came between how Franklin in “mezzo-soprano, the gospel Aretha Franklin felt and what she Detroit, growls, the throaty howls, the girl- ish vocal tickles, the swoops, the could express, between what she Michigan, in expressed and how we responded. dives, the blue-sky high notes, the January Blissful on “(You Make Me Feel blue-sea low notes. Female vocal- Like) a Natural Woman.” 1987. ists don’t get the credit as innova- Despairing on “Ain’t No Way.” tors that male instrumentalists do. Up front forever on her feminist As surely as Jimi Hendrix settled mid-20s, she recorded hundreds They should. Franklin has mas- and civil rights anthem “Respect.” arguments over who was the No. -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

Standard-Auswahl

Standard-Auswahl Nummer Titel Interpret Songchip 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING Standard 10807 1000 MILES AWAY JEWEL Standard 8002 19-2000 GORILLAZ Standard 8701 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR Standard 8004 25 MINUTES MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK Standard 8702 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS Standard 8005 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN Standard 10808 4 TO THE FLOOR STARSAILOR Standard 8006 05:15:00 THE WHO Standard 8703 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL Standard 10050 93 MILLION MILES 30 SECONDS TO MARS Standard 8007 99 RED BALLOONS NENA Standard 8008 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS Standard 8704 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER Standard 10052 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY Standard 9009 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. Standard 9010 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. Standard 8009 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS Standard 10053 A LONG WALK JILL SCOTT Standard 8010 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN Standard 9011 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. Standard 8011 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT Standard 8705 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN Standard 10055 A PLACE FOR MY HEAD LINKIN PARK Standard 8012 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER Standard 10809 A SONG FOR THE LOVERS RICHARD ASHCROFT Standard 10057 A SONG FOR YOU THE CARPENTERS Standard 9013 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. Standard 10058 A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON Standard 9014 A WANDERING MINSTREL P.D. Standard 8013 A WHITER SHADE OF PALE PROCOL HALUM Standard 8014 A WOMAN'S WORTH ALICIA KEYS Standard 8706 A WONDERFUL DREAM THE MAJORS Standard 10059 AARON'S PARTY (COME GET IT) AARON CARTER Standard 8016 ABC THE JACKSON 5 Standard 8017 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA Standard 10060 ACCIDIE CAPTAIN Standard 10061 ACHY BREAKY HEART BILLY RAY CYRUS Standard 10062 ADRIENNE THE CALLING Standard 10063 AFTER ALL AL JARREAU Standard 8019 AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE EARTH, WIND & FIRE Standard 10064 AFTERNOONS & COFFEESPOONS CRASH TEST DUMMIES Standard 8020 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ Standard 10810 AGAIN AND AGAIN THE BIRD AND THE BEE Standard 10066 AGE AIN'T NOTHING BUT A AALIYAH Standard 8707 NUMAIN'TBE MIRSBE HAVIN' HANK WILLIAMS, JR. -

Kansas – Point of Know Return Live

Kansas – Point Of Know Return Live & Beyond (43:41 + 68:31, CD, Digital, Vinyl, InsideOut Music / Sony Music, 2021) Nach diversen Umbesetzungen vor einigen Jahren ist das amerikanische Progschlachtschiff Kansas wieder schwer auf Kurs. Man legte nach dem geglückten Neustart mit The„ Prelude Implicit“ (2016) und besonders „The Absence Of Presence“ (2020) nicht nur zwei prächtige Studioalben vor, auch live präsentiert sich die Band nach der alterstechnischen Blutauffrischung vitaler denn je. Deswegen geht ebenfalls „Live & Beyond“ in die zweite Runde. Vor rund drei Jahren würdigte man bereits den 76er Klassiker „Leftoverture“ in seiner Gesamtheit im Livekontext, jetzt folgt der zweite, ebenfalls verkaufstechnisch sehr erfolgreiche Platinum Seller „Point Of Know Return“. Wies das erste „Live & Beyond“ Package noch einige Makel auf, besonders durch die massive Verwendung von Autotune bei den Gesangspassagen, so macht die Band dieses Mal alles richtig. Gerade der Steve Walsh Nachfolger Ronnie Platt hat anscheinend wesentlich mehr an Vertrauen in seine eigene Stimmkraft gewonnen und liefert eine perfekte Performance voller vokaler Leidenschaft ab. Natürlich gibt es einige Überschneidungen mit dem letzten Livepackage, da man eben nicht grundsätzlich auf „Leftoverture“ Klassiker wie ‚The Wall‘, ‚Miracles Out Of Nowhere‘ und dem unverwüstlichen ‚Carry On Wayward Son‘ verzichten wollte. Doch neben dem kompletten 77er Album „Point Of Know Return“ bietet man einen sehr gut austarierten Mix aus Klassikern, neuem Material (u.a. ‚Summer‘ und ‚Refugee‘ von „The Prelude Implicit“), aber auch selten gehörtes Material wie das äußerst dynamisch interpretierte ‚Two Cents Worth‘ von „Masque“ (1975) oder die ursprünglich vonSteve Morse geprägten ‚Musicatto / Taking In The View‘ von „Power“ (1986). Was aber in erster Linie überzeugt, ist die Hingabe, Spielfreude und unglaubliche Power, die die aktuelle Kansas Besetzung auf der Bühne bietet. -

Peggy Lee Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ—¶É—´È¡¨)

Peggy Lee 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) The Man I Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-man-i-love-7749873/songs Pass Me By https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pass-me-by-7142400/songs Beauty and the Beat! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beauty-and-the-beat%21-4877929/songs Mirrors https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mirrors-6874686/songs Jump for Joy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/jump-for-joy-6311166/songs Sugar 'n' Spice https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sugar-%27n%27-spice-7634729/songs Miss Wonderful https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/miss-wonderful-3036741/songs Close Enough for Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/close-enough-for-love-5135199/songs Pretty Eyes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pretty-eyes-7242220/songs Let's Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/let%27s-love-6532481/songs Blues Cross Country https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/blues-cross-country-4930454/songs Somethin' Groovy! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/somethin%27-groovy%21-7560012/songs Things Are Swingin' https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/things-are-swingin%27-7784352/songs Latin ala Lee! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/latin-ala-lee%21-6496491/songs Mink Jazz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mink-jazz-6867800/songs If You Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/if-you-go-5990922/songs Big $pender https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/big-%24pender-4904872/songs I Like Men! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/i-like-men%21-5977966/songs -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

New AV List for November 2020

NEW AV MATERIALS November 2020 CD Title Call # Author After hours CD Wee (Pop/Rock) Weeknd Agricultural tragic CD Lun (Country Music) Lund, Corb Alicia CD Key (Pop/Rock) Keys, Alicia Alive CD Eag (Country Music) Eaglesmith, Fred J. All rise CD Por (Jazz) Porter, Gregory All that emotion CD Geo (Pop/Rock) Georgas, Hannah American standard CD 389 Tay (Pop/Rock) Taylor, James Angel Miners & The CD Awo (Pop/Rock) AWOLNATION Lightning Riders Artemis CD Art (Jazz) Artemis B7 CD Bra (Pop/Rock) Brandy Bigger love CD Leg (Pop/Rock) Legend, John Blackbirds CD Lav (Blues) LaVette, Bettye Bless your heart CD All (Pop/Rock) Allman Betts Band Blessed songs of CD Bri (Christian/Gospel) Brickman, Jim inspiration Born here live here die CD Bry (Country Music) Luke, Bryan here Brightest blue CD Gou (Pop/Rock) Goulding, Ellie Calm CD Fiv (Pop/Rock) 5 Seconds of Summer Can we fall in love CD Ava (Pop/Rock) Avant Ceelo Green is Thomas CD Gre (Pop/Rock) Green, Ceelo Callaway Chromatica CD Lad (Pop/Rock) Lady Gaga Church house blues CD Sha (Blues) Shawanda, Crystal Circles CD Mil (Rap) Miller, Mac Crave CD Kie (Pop/Rock) Kiesza Dedicated side B CD Jep (Pop/Rock) Jepsen, Carly Rae Easy to buy, hard to sell CD Sle (Pop/Rock) Sleep Eazys Echoes CD Jer (Folk music) Jerry Cans Eleven words CD Fos (Instrumental) Foster, David Ella 100 live at The Apollo! CD Ell (Jazz) Various artists Everything means nothing CD Bla (Blues) Blackbear Fetch the bolt cutters CD App (Pop/Rock) Apple, Fiona First rose of spring CD Nel (Country Music) Nelson, Willie Folklore CD Swi (Pop/Rock)