Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Iv : Concluding Remarks

SECTION IV : CONCLUDING REMARKS 1. Stage One of the public consultation programme for the HK2030 Study formally concluded in April 2001, having established a benchmark for future public consultation exercises. We consider that the public consultation programme has secured a sound basis for continuous dialogue with both the general public and stakeholder groups about the many issues raised by the study. The findings of the Stage One consultation process will serve as important input to the study process. 2. We are currently devoting our efforts to the examination of the key study areas and the many ideas/suggestions that have been received in the consultation exercise. 3. In addition to the examination of the key study areas, we are developing evaluation criteria based on the revised planning objectives. The issues identified in the study process and the evaluation criteria will be consolidated and presented for comment during the Stage Two public consultation exercise, which is scheduled to take place towards the end of 2001. 4. We hope this Stage One Public Consultation Report provides a solid foundation for further community discussion and exchange of views regarding the HK2030 Study. In this regard, we intend to organise a briefing for interested parties to explain and elaborate on the various responses provided in this report. Meanwhile, we welcome any further views which can be addressed to: HK2030 Feedback Co-ordinator Planning Department, Strategic Planning Section 16/F. North Point Government Offices 33 Java Road North Point Fax -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Legislative Council Brief

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF PUBLIC HEALTH AND MUNICIPAL SERVICES DESIGNATION OF PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND North Lamma Public Library In connection with the “Signature Project Scheme (Islands District) - Yung Shue Wan Library cum Heritage and Cultural Showroom, Lamma Island” (Project Code: 61RG), the North Lamma Public Library (NLPL) which was originally located in a one-storey building near Yung Shue Wan Ferry Pier was demolished for constructing a three-storey building to accommodate the Heritage and Cultural Showroom on the ground floor and Yung Shue Wan Public Library on the first and the second floors. Upon completion of the project, the library will adopt the previous name as “North Lamma Public Library”(南丫島北段公共圖書館) and it is planned to commence service in the second quarter of 2019. Self-service library station 2. Besides, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (“LCSD”) has earlier launched a pilot scheme to provide three self-service library stations (“library station”), one each on Hong Kong Island, in Kowloon and in the New Territories. The library stations provide round-the-clock library services such as borrowing, return, payment and pickup of reserved library materials. 3. The locations of the three library stations are the Island East Sports Centre sitting-out area in the Eastern District, outside the Studio Theatre of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre in the Yau Tsim Mong District and an outdoor area near the Tai Wai MTR Station in the Sha Tin District respectively. The first library station in the Eastern District was opened on 5 December 2017 while the remaining two in the Yau Tsim Mong District and the Sha Tin District are tentatively planned to be opened in the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019 respectively. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/SS/9/12 LC Paper No. CB(2)426/13-14 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Subcommittee on District Councils Ordinance (Amendment of Schedule 3) Order 2013 Minutes of the third meeting held on Saturday, 12 October 2013, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Claudia MO Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, BBS, MH, JP Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP Hon TANG Ka-piu Hon Christopher CHUNG Shu-kun, BBS, MH, JP Members : Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, JP absent Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon WONG Yuk-man Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon CHAN Han-pan Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Dr Hon Helena WONG Pik-wan Public Officers : Mr Gordon LEUNG attending Deputy Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Ms Anne TENG Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs - 2 - Miss Selina LAU Senior Government Counsel Department of Justice Mr Ronald CHAN Political Assistant to Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Attendance by : Right of People's Livelihood & Legal Association HK invitation Mr Tim LEE President Civic Party Mr LOUIE Him-hoi Kowloon East District Developer Democratic Party Mr TSOI Yiu-cheong Convenor, Constitutional Group Mr Raymond HO Man-kit Member of Sai Kung District -

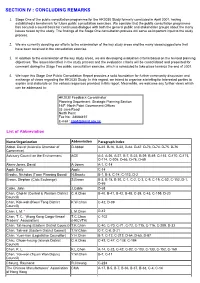

List of Abbreviations

MJ T`Wbb_b] M^c_Y[f 0;BC ?: +66A9E;5C;?> Q_fg c\ KXXe[i_Wg_cb List of Abbreviation Name/Organization Abbreviation Paragraph Index Advisory Council on the Environment ACE A3-1, A4-21, B1-24, C1-54, C4-13, C7-3, C7-18, C9-8, D4-1, D5-3 Advisory Council on the Environment – ACE-EIA Subcom B1-1, B2-5, C4-50, C7-6, C7-9, Environmental Impact Assessment C7-16, D3-2, D6-32, D9-9 Subcommittee Antiquities Advisory Board AAB A4-22, A4-33, B1-1, D5-13, D5-18, D5-33 Apple Daily Apple C4-30, D2-1, D3-1, D3-10, D10-32 Au, Joanlin Chung Leung J. Au B2-19, D10-10 Best Galaxy Ltd. BG Ltd. C4-19, C4-27, C4-49 Charter Rank Ltd. CR Ltd. Brown, Stephen S. Brown B1-1, B1-2, B1-16, B1-17, B1-23, D2-1, D2-9, D2-14, D5-15, D5-20, D8-1 Central & Western District Council C&W DC A2-12, B1-1, C3-3, C3-17, C3-20, C4-65, D2-1, D2-3, D2-4, D2-16, D3-14, D5-19, D5-29, D5-31, D9-1, D9-8, D10-21 Chan, Albert W.Y. A. Chan D2-14 Chan, Ho Kai* H.K. Chan C3-13, C4-1, D5-37, D5-39 Chan, Ling* L. Chan A4-25, D10-4 Chan, Raymond R. Chan A4-9, B1-7, C2-15, C2-19, C2-50, Cheng, Samuel S. Cheng C3-10, D6-4, D6-7, D6-19, D6-29, Kwok, Sam S. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

(Translation) Islands District Council Minutes of Meeting of The

(Translation) Islands District Council Minutes of Meeting of the Community Affairs, Culture and Recreation Committee Date : 4 September 2018 (Tuesday) Time : 2:00 p.m. Venue : Islands District Council Conference Room Present Ms YU Lai-fan (Chairman) Ms TSANG Sau-ho, Josephine (Vice-Chairman) Mr CHOW Yuk-tong, SBS Mr YU Hon-kwan, Randy, JP Mr CHAN Lin-wai Ms LEE Kwai-chun Ms YUNG Wing-sheung, Amy Mr KWONG Koon-wan Mr KWOK Ping, Eric Ms FU Hiu-lam Sammi Mr WONG Hoi-yu Mr LAI Tsz-man Ms KWOK Wai-man, Mealoha Ms YIP Sheung-ching Attendance by Invitation Chief Health Inspector (Islands)2, Ms LAW Wai-chun Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Property Service Manager/Service (Hong Kong Island and Miss SZETO Hau-yan, Esther Islands 3), Housing Department Miss CHOI Siu-man, Sherman Senior Transport Officer/Islands1, Transport Department In Attendance Ms CHAN Sok-fong, Cherry Deputy District Leisure Manager (District Support) Islands, Leisure and Cultural Services Department Ms KWOK Lai-kuen, Elaine Senior Librarian (Islands), Leisure and Cultural Services Department Ms YIP Siu-kuen, Cecilia Assistant Manager (New Territories South) Marketing & District Activities, Leisure and Cultural Services Department Mr WONG Kin-sun, Frederick Senior Community Relations Officer (Hong Kong West/Islands), Independent Commission Against Corruption Dr LEE Chi-on, Clement Senior School Development Officer (Islands)1, Education Bureau Mr NG Wai-lung, David Assistant District Social Welfare Officer (Central Western, Southern and Islands)2, Social Welfare Department -

Islands District Council Paper No. IDC 89/2020

Islands District Council Paper No. IDC 89/2020 Improvement Works at Tai O, Phase 2 Stage 2 PURPOSE This paper aims at presenting the design proposal of the Improvement Works at Tai O, Phase 2 Stage 2 and to seek Members’ views and support on the proposed improvement works. BACKGROUND 2. Further to the “Improvement Works for Tai O Facelift - Feasibility Study”, the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) proposed to carry out improvement works at Tai O in phases in order to improve the living quality and enhance the environment at Tai O. The riverwall of Phase 1 works and the public open space, public transport terminus and public car park of Phase 2 Stage 1 works were completed accordingly. Phase 2 Stage 2 works are currently under detailed design. PROPOSED PROJRCT SCOPE 3. In an effort to enhance the connectivity of the Tai O riversides and the pedestrian accessibility within Tai O, we recommend to construct two footbridges at Yim Tin and Po Chue Tam respectively. Yim Tin Footbridge will connect Yim Tin and Sun Ki Street; whereas Po Chue Tam Footbridge will connect Kat Hing Back Street and Sun Ki Street. Besides, the footbridges will serve as emergency vehicular access to different places. The improvement works also include the construction of community and cultural event space and public car park at Yim Tin, landscaping and associated works at the garden in front of the Yeung Hau Temple. 4. The proposed project scope comprises: (i) Construction of footbridge at Yim Tin; (ii) construction of footbridge at Po Chue Tam ; (iii) proposed community and cultural event space and provision of cars parking spaces at Yim Tin; and (iv) landscaping and associated works at the garden in front of the Yeung Hau Temple. -

Jockey Club Age-Friendly City Project

Table of Content List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. i List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Overview and Trend of Hong Kong’s Ageing Population ................................ 3 1.2 Hong Kong’s Responses to Population Ageing .................................................. 4 1.3 History and Concepts of Active Ageing in Age-friendly City: Health, Participation and Security .............................................................................................. 5 1.4 Jockey Club Age-friendly City Project .............................................................. 6 2 Age-friendly City in Islands District .............................................................................. 7 2.1 Background and Characteristics of Islands District ......................................... 7 2.1.1 History and Development ........................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Characteristics of Islands District .......................................................... 8 2.2 Research Methods for Baseline Assessment ................................................... -

Islands Chapter 2

!"#$%&'()* !"#$%&'()* !"#$#%&'() !"#$!%&'()*+, - !"#$ !"#$%&'()*+,-. !"#$%&'( )*+,-. !"#$%&'()*+,-./ !"#$%&'()*+,-./ !"#$%&'()*+,-./ !"#$%&'()'*+,-. !"#$%&'()*+,-./ !"#$%&'()*+,-. !"#$%&'()*+,-. !"#$%&!'()*+,-.' !" ! !"#$%&' ! !"#$%&'() !"#$%&'() !"#$ ! !"#$%& !" !" !"#$%&'!( !"#$%&'() !"#$%&' NUP Section 2 Islands Chapter 2 he Islands District provides Hong Kong with a vast green space. In Tearly times people inhabited only a few islands. Among them the best-known are Cheung Chau and Tai O on Lantau Island; Mui Wo and Peng Chau are also important. Mr. Charles Mok, former CLP Organization Development Manager, and Mr. Cheng Ka Shing, former CLP Regional Manager, have been serving the people of the Islands District for many years. During the early years of the 1960s, Lord Lawrence Kadoorie initiated the expansion of the Rural Electrification Scheme to Lantau Island. At that time there were very few people (less !"# !"#$%&'() than 30 families) living in Ngong Ping and Ngong Ping, where the great Buddha Statue is situated, is the centre of Hong Kong’s Buddhism around Po Lin Monastery on Lantau Island. Ngong Ping got its electricity supply between 1964 and 1965, while the bungalows at Tai O had received electricity supply earlier. Since the bungalows were mainly built with iron sheets, the installation of electricity was very difficult. The people there used a kind of wood named “Kun Dian” as posts to hold the electric cables. NUQ !" ! Tai O was famous for its “bungalows” !"#$%&'()* !"#$%&'()* !"#$%&'()* -

A Case Study of Hong Kong YWCA, Tai O YICK, Man Kin A

Ecological Change and Organizational Legitimacy Repair: A Case Study of Hong Kong YWCA, Tai O YICK, Man Kin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology The Chinese University of Hong Kong August 2011 Abstract of thesis entitled: Ecological Change and Organizational Legitimacy Repair: A Case Study of Hong Kong YWCA, Tai O Submitted by YICK, Man Kin for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in August 2011 ii Abstract This thesis studies how an organization maintained its legitimacy in response to the changing ecology. Through this study, the dynamics between state and social service sector in Hong Kong in the past two decades will be illuminated. This study draws on concepts from literature on organizational legitimacy, stakeholder analysis, and nonprofit studies. Through a qualitative case study, I attempt to illustrate how a social service organization (SSO), Hong Kong YWCA, differed in strategies of legitimacy repair after challenges from a Tai O rural consultative body, government departments, and other parts of the society in two time periods: the District Board election in 1988 and post-disaster relief during 2008-10 (the River Crab Saga). I aim to provide an explanation of more consistent, unified, and less complied response in the earlier case but less consistent, unified and more compliance with stakeholders' demands in the latter case - the high level of change in salience among YWCA stakeholders in the latter dispute. Two factors resulted in such a change: 1) the less stable funding environment due to Lump Sum Grant System, and 2) the intensified struggle between pro-Beijing and pro-democracy factions due to party penetration of society and rise of popular political awareness. -

1 Registration and Electoral Office Annual Open Data Plan for 2018 A

Registration and Electoral Office Annual Open Data Plan for 2018 A. Departmental datasets to be released in 2019 Type of Data/ Name of Target Frequency of Update (e.g. real-time; daily; Remarks Dataset Release Date weekly; monthly …) (in mm/yyyy) Miscellaneous / No. of Reference data of no. of registered electors of registered electors of 10/2019 As and when necessary geographical constituencies in 2010 - 2019 geographical constituencies in (CSV) 2010 - 2019 Miscellaneous / No. of Reference data of no. of registered electors of registered electors of 10/2019 As and when necessary functional constituencies in 2010 - 2019 functional constituencies in (CSV) 2010 - 2019 Miscellaneous / No. of Reference data of no. of registered voters of registered voters of Election 10/2019 As and when necessary Election Committee subsectors in 2010 - 2019 Committee subsectors in 2010 (CSV) - 2019 Miscellaneous / Distribution Reference data of distribution of registered of registered electors by 10/2019 As and when necessary electors by geographical constituencies in geographical constituencies in 2019 (CSV) 2019 Miscellaneous / Sex profile of registered electors by Reference data of sex profile of registered 10/2019 As and when necessary geographical constituencies in electors in 2019 (CSV) 2019 Miscellaneous / Age and Sex Reference data of age and sex profile of profile of registered electors 10/2019 As and when necessary registered electors by Legislative Council by Legislative Council Constituencies in 2019 (CSV) Constituencies in 2019 1 Miscellaneous