University International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorne's Concept of the Creative Process Thesis

48 BSI 78 HAWTHORNE'S CONCEPT OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Retta F. Holland, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HAWTHORNEIS DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER 1 II. PREPARATION FOR CREATIVITY: PRELIMINARY STEPS AND EXTRINSIC CONDITIONS 21 III. CREATIVITY: CONDITIONS OF THE MIND 40 IV. HAWTHORNE ON THE NATURE OF ART AND ARTISTS 67 V. CONCLUSION 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii CHAPTER I HAWTHORNE'S DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER Early in his life Nathaniel Hawthorne decided that he would become a writer. In a letter to his mother when he was seventeen years old, he weighed the possibilities of entering other professions against his inclinations and concluded by asking her what she thought of his becoming a writer. He demonstrated an awareness of some of the disappointments a writer must face by stating that authors are always "poor devils." This realistic attitude was to help him endure the obscurity and lack of reward during the early years of his career. As in many of his letters, he concluded this letter to his mother with a literary reference to describe how he felt about making a decision that would determine how he was to spend his life.1 It was an important decision for him to make, but consciously or unintentionally, he had been pre- paring for such a decision for several years. The build-up to his writing was reading. Although there were no writers on either side of Hawthorne's family, there was a strong appreciation for literature. -

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist Series 1 - Fury Files Wave 1 • 001 - Iron Man (Modern Armor) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Light Paint Variant) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Dark Paint Variant) • 003 - Silver Surfer • 004 - Punisher • 005 - Black Panther • 006 - Wolverine (X-Force costume) • 007 - Human Torch (Flamed On) • 008 - Daredevil (Light Red Variant) • 008 - Daredevil (Dark Red Variant) • 009 - Iron Man (Stealth Ops) • 010 - Bullseye (Light Paint Variant) • 010 - Bullseye (Dark Paint Variant) • 011 - Human Torch (Light Blue Costume) • 011 - Human Torch (Dark Blue Costume) Wave 2 • 012 - Captain America (Ultimates) • 013 - Hulk (Green) • 014 - Hulk (Grey) • 015 - Green Goblin • 016 - Ronin • 017 - Iron Fist (Yellow Dragon) • 017 - Iron Fist (Black Dragon Variant) Wave 3 • 018 - Black Costume Spider-Man • 019 - The Thing (Light Pants) • 019 - The Thing (Dark Pants) • 020 - Punisher (Modern Costume & New Head Sculpt) • 021 - Iron Man (Classic Armor) • 022 - Ms. Marvel (Modern Costume) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Carol Danvers) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Karla Sofen) • 024 - Hand Ninja (Red) Wave 4 • 026 - Union Jack • 027 - Moon Knight • 028 - Red Hulk • 029 - Blade • 030 - Hobgoblin Wave 5 • 025 - Electro • 031 - Guardian • 032 - Spider-man (Red and Blue, right side up) • 032 - Spider-man (Black and Red, upside down Variant) • 033 - Iron man (Red/Silver Centurion) • 034 - Sub-Mariner (Modern) Series 2 - HAMMER Files Wave 6 • 001 - Spider-Man (House of M) • 002 - Wolverine (Xavier School) -

An Eden with No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in The

An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Joshua Gibbons Striker 2019 Abstract In this dissertation I use an old and unfashionable form of literary criticism, close reading, to offer a new and unfashionable account of the literary subgenre called camp. Drawing on the work of, among many others, Susan Sontag, Rita Felski, and Peter Lamarque, I argue that P.G. Wodehouse, E.F. Benson, and Angela Thirkell wrote a type of pure comedy I call chaste camp. Chaste camp is a strange beast. On the one hand it is a sort of children’s literature written for and about adults; on the other hand it rises to a level of literary merit that children’s books, even the best of them, cannot hope to reach. -

F, Sr.Auifuvi

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE' S USE OF WITCH AND DEVIL LORE APPROVED: Major Professor Consulting Professor Iinor Professor f, sr. auifUvi Chairman of" the Department of English Dean of the Graduate School Robb, Kathleen A., Nathaniel Hawthorne;s Fictional Use of Witch and Devil Lore. Master of Arts (English), December, - v 1970, 119 pp., bibliography, 19 titles. Nathaniel Hawthorne's personal family history, his boy- hood in the Salem area of New England, and his reading of works about New England's Puritan era influenced his choice of witch and Devil lore as fictional material. The witch- ci"aft trials in Salem were evidence (in Hawthorne's inter- pretation) of the errors of judgment and popular belief which are ever-present in the human race. He considered the witch and Devil doctrine of the seventeenth century to be indicative of the superstition, fear, and hatred which governs the lives of men even in later centuries. From the excesses of the witch-hunt period of New England history Hawthorne felt moral lessons could be derived. The historical background of witch and Devil lore, while helpful in illustrating moral lessons, is used by Hawthorne to accomplish other purposes. The paraphernalia of witchcraft with its emphasis on terrible and awesome ceremonies or practices such as Black Sabbaths, Devil compacts, image-magic, spells and curses, the Black Man in'the forest, spectral shapes, and familiar spirits is used by Hawthorne to add atmospheric qualities to his fiction. Use of the diabolic creates the effects of horror, suspense, and mystery. Furthermore, such 2 elements of witch and Devil doctrine (when introduced in The Scarlet Letter, short stories, and historical sketches) also provide an aura of historical authenticity, thus adding a v dimension of reality and concreteness to the author's fiction. -

Heffimw Jl Imf Jv 3Ip Mwwmmm E W5ws4n Mskm

9- BBMBBBBBjWPPW vjmEb 5 - TUlTi1iiiinrfrn Tiiiinrr r J 4 7 f 1 VOL XXXV No 6i HONOLULU TUESDA1 FEBRUAEY 5 18S9 i WHOLE No 1256 QTarits 7 Business Tau uDcrtiscmcnts SAM0AN Danielson in n saloon of laughing at itiv m - THE QUESTION IIIIIIX I sWt- SauiaiiandaMe a picture of tho dead Emperor of HiVM4Wv J ttU Germany Danielson denied having MISCELLANEOUS A B LOEBENSTEIN m done so when one of the officers rlTKLISUKl UY BISHOP COMPANY Surveyor anil Civi Engineer TUESDAY FEBRUARY 5 1S59 Considerable Excitement on the tried to throw him down Ho threw HAWAIIAN GAZETTE CO Limited Pacific Coast the officer instead and the second 1242 11ILO HAWAII 6m officer then stabbed him onco in BANKERS Every Tuesday Morning PERSONAL each arm with his sword When IIOXOMMJ HAWAIIAN ISLANDS A M SPROTIIiI Danielson went to tho German Con- ¬ Vivid Hostllltfe i FIVE DOLLARS PER ANMJM DRAW EXCHANGE ON Account of from Klein of Al AV clerk- ¬ sulate next morning to complain THE BANK OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO Civil Engineer and Surveyor Mr F Love is going to get a in the Examiner American and Ifi the two officers ho was told ho was PAYABLE IX ADVAXCE AND AGENTS IX ship the ro3toffice TIIEIB British Flags Insulted ¬ - - - Mr B Dillingham baby drunk and forced to leave the prem- SO 00 in Ailvnm c Sew VorJi Boston laris Tort Street Honolulu F has a Korei jn Subscribers Q2Jl 3m named initially O G ises MESSRS U ffl ROTHSCHILD SONS LONDON It L ¬ On the evening of the 16th about Which include postages prepaid ANKFORT-ON-TnE-MAIN- Mr J U Tucker promenaded in celes- ¬ --By the -

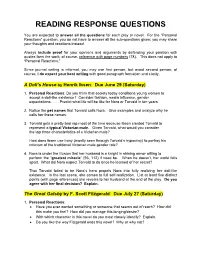

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

September 1914) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 9-1-1914 Volume 32, Number 09 (September 1914) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 32, Number 09 (September 1914)." , (1914). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/606 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE 625 Combs Broad Street Conservatory Greatest Educational Work of the Age Standard and Modern Mathews Standard Instruction Books Graded Course of for the Pianoforte THE SELECTION OF THE RIGHT MUSIC ■r^lna; Studies™ Pianoforte SCHOOL IS THE ALL IMPORTANT STEP Compiled by W. S. B. MATHEWS Individual attention, high ideals, breadth of culture, personal care and moderate cost of education at the COMBS BROAD ST. CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC should interest you !§pnmmmmMs. Three Decades of Success Teachers of World Wide Fame Can Accommodate 2500 Day and Dormitory GILBERT RAYNOLDS COMBS, Piano. Students. HENRY SCHRAD1ECK, Violin. iEssSItsI' Chartered by State of Pennsylvania with HUGH A. CLARKE, Mus. Doc., Theory and seventy artist teachers—graduates of the power to confer degrees. -

Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation from God and Man

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man. Lloyd Moore Daigrepont Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Daigrepont, Lloyd Moore, "Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3389. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3389 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

E.-Michael-Jones-Hawthorne-The-Angel-And-The-Machine.Pdf

FAITH & REASON THE JOURNAL OF CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE Fall 1982 | Vol. VIII, No. 3 Hawthorne: The Angel and the Machine E. Michael Jones Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) is justly famous as one of America’s premier novelists and short story writers. Over a writing career stretching from 1829 until his death, Hawthorne consistently probed the moral and spiritual conficts which he observed in his own life and, mainly, in the lives of the Puritan and Transcendentalist New Englanders with whom he spent most of his life. Both Puritanism and Transcendentalism, of course, deal with the material world and the human body in ways which tend to make them either confict with or irrelevant to the human spirit. Therefore, Hawthorne was never far in his works from a struggle with the fundamental identity of man as a unity of body and soul. As Michael Jones points out below The Blithedale Romance is a novel uniquely situated in Haw- thorne’s life and experience to lend itself to an illuminating examination of the confict within the author about human na- ture. This examination in turn sheds light on a whole chapter of American history as well as some of the recurring spiritual tensions of our own time. “He is a man, after all!” thought I--his Maker’s own truest image, a philanthropic man!-not that steel engine of the Devil’s contrivance, a philanthropist!”-But, in my wood-walks, and in my silent chamber, the dark face frowned at me again. “We must trust for intelligent sympathy to our guardian angels, if any there be,” said Zenobia. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1w33f4s5 Author Montoya, Aaron Tracy Publication Date 2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ PERFORMING CITIZENS AND SUBJECTS: DANCE AND RESISTANCE IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY MOZAMBIQUE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ANTHROPOLOGY with an emphasis in Visual Studies by Aaron Montoya June 2016 The Dissertation of Aaron Montoya is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Shelly Errington, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Carolyn Martin-Shaw ____________________________________ Professor Olga Nájera-Ramírez ____________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Aaron T. Montoya 2016 Table of Contents Abstract iv Agradecimientos vi Introduction 1 1. Citizens and Subjects in Portuguese Mozambique 20 2. N’Tsay 42 3. Nyau 84 4. Um Solo para Cinco 145 5. Feeling Plucked: Labor in the Cultural Economy 178 6. Conclusion 221 Bibliography 234 iii Abstract Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Aaron Montoya This dissertation examines the politics and economics of the cultural performance of dance, placing this expressive form of communication within the context of historic changes in Mozambique, from the colonial encounter, to the liberation movement and the post-colonial socialist nation, to the neoliberalism of the present. The three dances examined here represent different regimes, contrasting forms of subjectivity, and very different relations of the individual to society. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State