Continuity and Change of Cultural Practices in the Performing Arts: a Case Study of the Indian Diaspora in Perth ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disporia of Borders: Hindu-Sikh Transnationals in the Diaspora Purushottama Bilimoria1,2

Bilimoria International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:17 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0048-x Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access The disporia of borders: Hindu-Sikh transnationals in the diaspora Purushottama Bilimoria1,2 Correspondence: Abstract [email protected] 1Center for Dharma Studies, Graduate Theological Union, This paper offers a set of nuanced narratives and a theoretically-informed report on Berkeley, CA, USA what is the driving force and motivation behind the movement of Hindus and Sikhs 2School of Historical and from one continent to another (apart from their earlier movement out of the Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia subcontinent to distant shores). What leads them to leave one diasporic location for another location? In this sense they are also ‘twice-migrants’. Here I investigate the extent and nature of the transnational movement of diasporic Hindus and Sikhs crossing borders into the U.S. and Australia – the new dharmic sites – and how they have tackled the question of the transmission of their respective dharmas within their own communities, particularly to the younger generation. Two case studies will be presented: one from Hindus and Sikhs in Australia; the other from California (temples and gurdwaras in Silicon Valley and Bay Area). Keywords: Indian diaspora, Hindus, Sikhs, Australia, India, Transnationalism, Diaspoetics, Adaptation, Globalization, Hybridity, Deterritorialization, Appadurai, Bhabha, Mishra Part I In keeping with the theme of Experimental Dharmas this article maps the contours of dharma as it crosses borders and distant seas: what happens to dharma and the dharmic experience in the new 'experiments of life' a migrant community might choose to or be forced to undertake? One wishes to ask and develop a hermeneutic for how the dharma traditions are reconfigured, hybridized and developed to cope and deal with the changed context, circumstances and ambience. -

Quote of the Week

31st October – 6th November, 2014 Quote of the Week Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, ambition inspired, and success achieved. – Helen Keller < Click icons below for easy navigation > Through Chennai This Week, compiled and published every Friday, we provide information about what is happening in Chennai every week. It has information about all the leading Events – Music, Dance, Exhibitions, Seminars, Dining Out, and Discount Sales etc. CTW is circulated within several corporate organizations, large and small. If you wish to share information with approximately 30000 readers or advertise here, please call 98414 41116 or 98840 11933. Our mail id is [email protected] Entertainment - Film Festivals in the City Friday Movie Club @ Cholamandal presents - Film: BBC Modern Masters - Andy Warhol The first in a four-part series exploring the life and works of the 20th century's artists: Matisse; Picasso; Dali and Warhol. In this episode on Andy Warhol, Sooke explores the king of Pop Art. On his journey he parties with Dennis Hopper, has a brush with Carla Bruni and comes to grips with Marilyn. Along the way he uncovers just how brilliantly Andy Warhol pinpointed and portrayed our obsessions with consumerism, celebrity and the media. This film will be screened on 31st October, 2014 at 7.00 pm - 8.30 pm. at Cholamandal Centre for Contemporary Art (CCCA), Cholamandal Artists’ Village, Injambakkam, ECR, Chennai – 600 115. Entry is free. For more information, contact 9500105961/ 24490092 / 24494053 Entertainment – Music & Dance Bharat Sangeet Utsav 2014 Bharat Sangeet Utsav, organised by Carnatica and Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha is a well-themed concert series and comes up early in November. -

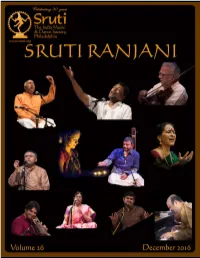

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

25 the Lighthouse 15 Dec 2020

Issue 31 • FEBRUARY 4, 2021 Rotary designated month FEBRUARY 2021 Peace and Conflict Prevention or Resolution Month THE LIGHTHOUSE • FEBRUARY 4, 2021 2 EDITORIAL Let’s bring out the BIG GUNS against Polio! BIRTHDAYS Greetings dear Rotarians. From a conversational and poignant meeting with Niren Chaudhary 18th Feb – Rtn. Punkaj Sachdev just 2 days earlier, we jumped into a passionate and electrifying one with none other than the Big Boss of Rotary in fighting polio - Rtn. Mike 20th Feb – Rtn. Ashok Doshi McGovern himself, talking about what looks like our last lap in this long race and finding that burst of energy to fly past the finish line, as 22nd Feb – Rtn. Archana Shri well as the challenges we face. Joining him was a battery of Sanjay committed stalwarts from the Rotary super-army. Indeed, it felt like the 19th Feb – Ann. Jyothi (Rtn. Ashok very air was charged with renewed vigour to fight against the deadly Bajaj) disease, listening to these Rotarians speak about our mission statement and how we can make it happen. Lighthouse this week is dedicated to 19th Feb – Ann. Sangeeta (Rtn. Rotary’s fight against this debilitating disease; a fight that’s sometimes Vijay Dugar) celebrated, sometimes unsung, but always marching on, full throttle... 20th Feb – Ann. Niyati (Rtn. Abhay Mehta) - Rtn. Shri Shakthi Girish 20th Feb – Ann. Reena (Rtn NEXT MEETING Rajasekar Gorantla) ANNIVERSARIES 16th Feb – Rtn. Dr. Sharon Krishna Rau & G. Lakshminarayan 16th Feb – Rtn. Ramakanth Akula & Ann. Niharika 16th Feb – Rtn. Siddharth Ganeriwala & Ann. Harsha Sajnani 17th Feb – Rtn. Anil Srinivasan & Ann. -

Cultural Profiles for Health Care Providers

Queensland Health CCoommmmuunniittyy PPrrooffiilleess for Health Care Providers Acknowledgments Community Profiles for Health Care Providers was produced for Queensland Health by Dr Samantha Abbato in 2011. Queensland Health would like to thank the following people who provided valuable feedback during development of the cultural profiles: x Dr Taher Forotan x Pastor John Ngatai x Dr Hay Thing x Ianeta Tuia x Vasanthy Sivanathan x Paul Khieu x Fazil Rostam x Lingling Holloway x Magdalena Kuyang x Somphan Vang x Abel SIbonyio x Phuong Nguyen x Azeb Mussie x Lemalu Felise x Nao Hirano x Faimalotoa John Pale x Surendra Prasad x Vaáaoao Alofipo x Mary Wellington x Charito Hassell x Rosina Randall © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2011. This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 2.5 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/au. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute Queensland Health. For permissions beyond the scope of this licence contact: Intellectual Property Officer Queensland Health GPO Box 48 Brisbane Queensland 4001 email [email protected] phone 07 3234 1479 Suggested citation: Abbato, S. Community Profiles for Health Care Providers. Division of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health. Brisbane 2011. i www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural Table of contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ -

Table of Contents Vidya Ramachandran

Table of Contents Privileged Hybrids: Examining ‘our own’ in the Indian-Australian diaspora ................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 Data collection and methodology ..................................................................................... 3 The Indian diaspora in Australia: navigating ‘Indianness’ and ‘Australianness’ ........... 4 Towards ‘Indianness’: the gradual dissolution of regional/linguistic identity ................. 7 ‘Hinduness’ and ‘Indianness’ .......................................................................................... 8 A model minority ............................................................................................................ 9 Unpacking caste: privilege and denial ........................................................................... 10 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 13 Vidya Ramachandran 1 Privileged Hybrids: Examining ‘our own’ in the Indian-Australian diaspora Introduction In April, the ‘Indian Wedding Race’ hit television screens across Australia (Cousins 2015). The first segment in a three-part series on multicultural Australia distributed by the SBS, the documentary follows two young Indian-Australians in their quest to get married before the age of thirty. Twenty-nine year-old Dalvinder Gill-Minhas was born and raised in Melbourne. Dalvinder’s family members are -

The Journal of the Music Academy Madras Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

The Journal of Music Academy Madras ISSN. 0970-3101 Publication by THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar (Tamil) Part I, II & III each 150.00 Part – IV 50.00 Part – V 180.00 The Journal Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar of (English) Volume – I 750.00 Volume – II 900.00 The Music Academy Madras Volume – III 900.00 Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Volume – IV 650.00 Volume – V 750.00 Vol. 89 2018 Appendix (A & B) Veena Seshannavin Uruppadigal (in Tamil) 250.00 ŸÊ„¢U fl‚ÊÁ◊ flÒ∑ȧá∆U Ÿ ÿÊÁªNÔUŒÿ ⁄UflÊÒ– Ragas of Sangita Saramrta – T.V. Subba Rao & ◊jQÊ— ÿòÊ ªÊÿÁãà ÃòÊ ÁÃDÊÁ◊ ŸÊ⁄UŒH Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in English) 50.00 “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; Lakshana Gitas – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman 50.00 (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra The Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin 50.00 (Sanskrit Text with supplement) E Krishna Iyer Centenary Issue 25.00 Professor Sambamoorthy, the Visionary Musicologist 150.00 By Brahma EDITOR Sriram V. Raga Lakshanangal – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in Tamil) Volume – I, II & III each 150.00 VOL. 89 – 2018 VOL. COMPUPRINT • 2811 6768 Published by N. Murali on behalf The Music Academy Madras at New No. 168, TTK Road, Royapettah, Chennai 600 014 and Printed by N. Subramanian at Sudarsan Graphics Offset Press, 14, Neelakanta Metha Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 014. Editor : V. Sriram. THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS ISSN. -

Engagement with Asia: Time to Be Smarter

Securing Australia's Future By Simon Torok and Paul Holper, 208pp, CSIRO Publishing, 2017 2 Engagement with Asia: time to be smarter You can’t do Asia with a Western head, Western thinking. Australian businesses miss opportunities because of a mindset that ‘Aussies know best’. Aussies need to change the way they think about their business. Chinese executive, quoted in SAF11 Australia’s Diaspora Advantage Golden thread Australia must celebrate its relationships in the Asia-Pacific region. We need to engage better and cement Australia’s prominent place in the region. Finding these new opportunities must embrace the invaluable resources of Asian and Pacific communities by improving Australia’s language ability, increasing cultural awareness, building on current export strengths and extending networks and linkages. Key findings This objective distils the interdisciplinary research and evidence from the 11 reports published as part of ACOLA’s Securing Australia’s Future project. To meet this objective, the following six key findings for improving Australia’s smart engagement with Asia and the Pacific need to be addressed: 1. Incentives are required to improve Australia’s linguistic and intercultural competence at school, university, and in the workplace. 2. We need to increase Australia’s ‘soft power’ through cultural diplomacy that updates perceptions of Australia in the Asia-Pacific region, and brings into the 21st century the way Australians see our place in the world. 23 © Australian Council of Learned Academies Secretariat Ltd 2017 www.publish.csiro.au Securing Australia's Future By Simon Torok and Paul Holper, 208pp, CSIRO Publishing, 2017 24 Securing Australia’s Future 3. -

Community Profiles for Health Care Providers Was Produced for Queensland Health by Dr Samantha Abbato in 2011

Queensland Health CCoommmmuunniittyy PPrrooffiilleess for Health Care Providers Acknowledgments Community Profiles for Health Care Providers was produced for Queensland Health by Dr Samantha Abbato in 2011. Queensland Health would like to thank the following people who provided valuable feedback during development of the cultural profiles: • Dr Taher Forotan • Pastor John Ngatai • Dr Hay Thing • Ianeta Tuia • Vasanthy Sivanathan • Paul Khieu • Fazil Rostam • Lingling Holloway • Magdalena Kuyang • Somphan Vang • Abel SIbonyio • Phuong Nguyen • Azeb Mussie • Lemalu Felise • Nao Hirano • Faimalotoa John Pale • Surendra Prasad • Vaáaoao Alofipo • Mary Wellington • Charito Hassell • Rosina Randall © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2011. This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 2.5 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/au. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute Queensland Health. For permissions beyond the scope of this licence contact: Intellectual Property Officer Queensland Health GPO Box 48 Brisbane Queensland 4001 email [email protected] phone 07 3234 1479 Suggested citation: Abbato, S. Community Profiles for Health Care Providers. Division of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health. Brisbane 2011. i www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural Table of contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ -

UNITED INDIAN ASSOCIATIONS Inc. Incorporation No: Y 2133 744

UNITED INDIAN ASSOCIATIONS Inc. Incorporation No: Y 2133 744 PO Box 9682, Harris Park NSW 2150 Australia www.uia.org.au Over 25 years of Community Service President UIA Media Release Date : 22-02-2021 Dr. Sunil Vyas [email protected] AUSTRALIA DAY & INDIAN REPUBLIC DAY CELEBRATION Vice President Mr. Dave Passi [email protected] United Indian Associations (UIA) proudly celebrated the dual Australia Day/Indian Republic Day of 26th January 2021 as a Virtual Secretary Event and also posted on Social Media. Mr. Satish Bhadranna [email protected] The constitution of India was formulated on Republic Day meanwhile the significance of Australia Day is evolving over time Joint Secretary Ms. Dimple Jani and in many respects reflects the nation's diverse peoples. [email protected] Not surprisingly 26th January is a special day for Australian-Indians who have a love for both these nations. Treasurer Mr. Onkaraswamy Goppenalli [email protected] Joint Treasurer Mr. Kiran Desai [email protected] Public Officer Mr. Vijaykumar Halagali [email protected] Honorary Legal Adviser Mr. Mohan Sundar Sunlegal-Blacktown [email protected] Member Associations: ● Australian Indian Medical The Event was opened by UIA Secretary Satish Bhadranna followed Graduates Association.Inc by singing of the national anthems "Advance Australia Fair" and ● Basava Samithi Australasia. "Jana Gana Mana". The rendition of each anthem by well-known Inc singer Ms Shobha Ingleshwar evoked feelings of patriotism and ● Bengali Assn. of NSW Inc. reminded people of the glory and rich heritage of both nations. Gujarati Samaj of NSW ● India Sports Club Inc. -

![Nation, Diaspora, Trans-Nation Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Nation, Diaspora, Trans-Nation](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1071/nation-diaspora-trans-nation-downloaded-by-university-of-defence-at-01-31-24-may-2016-nation-diaspora-trans-nation-1981071.webp)

Nation, Diaspora, Trans-Nation Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Nation, Diaspora, Trans-Nation

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Nation, Diaspora, Trans-nation Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Nation, Diaspora, Trans-nation Reflections from India Ravindra K. Jain Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI First published 2010 by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Ravindra K. Jain Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 Printed and bound in India by Baba Barkha Nath Printers MIE-37, Bahadurgarh, Haryana 124507 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-59815-6 For Professor John Arundel Barnes Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ix Introduction A World on the Move 1 Chapter One Reflexivity and the Diaspora: Indian Women in Post-Indenture Caribbean, Fiji, Mauritius, and South Africa -

Study of Discrimination in the Matter of Religious Rights and Practice

STUDY OF DISCRIMINATION IN THE MATTER OF RELIGIOUS RIGHTS AND PRACTICES by Arcot Krishnaswami Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities UNITED NATIONS STUDY OF DISCRIMINATION IN THE MATTER OF RELIGIOUS RIGHTS AND PRACTICES by Arcot Krishnaswami Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities UNITED NATIONS New York, 1960 Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. E/CN.4/Sub.2/200/Rev. 1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Catalogue No.: 60. XIV. 2 Price: $U.S. 1.00; 7/- stg.; Sw. fr. 4.- (or equivalent in other currencies) NOTE The Study of Discrimination in the Matter of Religious Rights and Practices is the second of a series of studies undertaken by the Sub- Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities with the authorization of the Commission on Human Rights and the Economic and Social Council. A Study of Discrimination in Education, the first of the series, was published in 1957 (Catalogue No. : 57.XIV.3). The Sub-Commission is now preparing studies on discrimination in the matter of political rights, and on discrimination in respect of the right of everyone to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. The views expressed in this study are those of the author. m / \V FOREWORD World-wide interest in ensuring the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion stems from the realization that this right is of primary importance.