A Comparative Study of the Record Keeping Practices Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (11MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] "THE TRIBE OF DAN": The New Connexion of General Baptists 1770 -1891 A study in the transition from revival movement to established denomination. A Dissertation Presented to Glasgow University Faculty of Divinity In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Frank W . Rinaldi 1996 ProQuest Number: 10392300 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10392300 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

Winter-2008.Pdf

VA OHIO VALLEY J.Blaine Hudson Vice Chairs Judith K.Stein,M.D. HISTORY STAFF University ofLouisville Otto Budig Steven Steinman lane Garvey Merrie Stewart Stillpass Editors R.Douglas Hurt Dee Gettler John M.Tew,Jr.,M.D. Christopher Phillips Purdue University Robert Sullivan James L.Turner DepartnientofHutory At Vontz,III Cincinnati James C. Klotter Treasurer University of Joey D.Williams MarkJ.Hauser Georgetown College Gregory Wolf A.Glenn Crothers Department ofHistory Bruce Levine Secretary THE FILSON University ofLouisville Uniwisity ofIllinois Martine R. Dunn at HISTORICAL Director GfResearch Urbana-Champaign SOCIETY BOARD OF Fbe Fihon Historical Society President and CEO DIRECTORS Harry N. Scheiber Douglass W McDooald Managing Editors UitioersityCalifoi' < nia at President Erin Clephas Berkeley Vice President of 7be Filson Historical Society Museums Orme Wilson,III Steven M. Stowe Tonya M.Matthews Ruby Rogers Indiana University Secretary Cincinnati Mt,3ftim Center David Bohl Margaret Roger D.Tate Cynthia Booth Barr Kulp EditorialAssistant Somerset Community College Stephanie Byrd Treasurer Brian Gebhat John E Cassidy J Walker Stites,m Department ofHistory Joe W.Trotter,Jr. David Davis Edwad D. Diller University ofCincit:,tati Carnegie Mellon University David L.Armstrong Deanna Donnelly J.McCauley Brown Editorial Board Altina Walier James Ellerhorst S.Gordon Dabney Stephen Aron University of Connecticut David E.Foxx Louise Farnsley Gardner Univer:ity ofCatifornia at Richard J.Hidy Holly Gathright LosAngeles CINCINNATI Francine S. Hiltz A.Stewart Lussig, MUSEUM CENTER Ronald A. Koetters 7homas T Noland,Jr. Joan E.Cashin BOARD OF Gary Z.Lindgren Anne Brewer Ogden Obio State Univmity TRUSTEES Kenneth W.Lowe H. Powell Starks Shenan R Murphy Ellen T.Eslinger Chair Robert W.Olson John R Stern William M. -

Baptist History and Distinctives

Baptist History and Distinctives What’s The Big Deal About Being a Baptist? "Ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints." (Jude 1:3) STUDENT EDITION NAME ___________________________________ By Pastor Craig Ledbetter, Th.G., B.A. Part of the Teaching Curriculum of Cork Bible Institute Unit B, Enterprise park Innishmore, Ballincollig, Cork, Ireland +353-21-4871234 [email protected] www.biblebc.com/cbi © 2018 Craig Ledbetter, CBI Baptist History and Distinctives Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Baptist Ignorance ............................................................................................................ 6 First Century Patterns to Follow ....................................................................................... 9 The Right Kind of Baptist ................................................................................................27 A Brief History of the Baptists .........................................................................................37 Baptists in America .........................................................................................................55 Baptist History Chart ......................................................................................................62 Baptists in Modern Europe ..............................................................................................64 Bibliography ...................................................................................................................66 -

Council of the North Prayer Cycle

Council of the North Prayer Cycle The Council of the North began in 1970 when the National Executive Council of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada appointed a taskforce to consider the challenges and opportunities for ministry in the northern parts of Canada. The following year this taskforce was replaced with the Primate’s Task- force on the Church in the North. In 1973 this taskforce became the Primate’s Council on the North. By 1976 this body had evolved into the present Council of the North. The Council of the North is made up of all bishops of the assisted diocese. They administer the General Synod’s grants for northern mission. The council meets twice a year to consider the needs of the mission and ministry of the Church in the north. It reports to both the Council of General Synod and to the meeting of The shaded area highlights the geography of the Council General Synod. of the North. 85% of the land. 15 % of the people. Our strength! Our challenge! Our ministry! The Bishops of the Council of the North believe that their purpose is, under God, to equip one another in their mission to enormous and thinly populated dioceses; The Council of the North is a grouping of financially assisted dioceses, which are to offer mutual encouragement and pastoral care, hope to the oppressed, and chal- supported through grants by General Synod. There are 9 dioceses, the Anglican lenge to the complacent. In all they do, they strive to be a sign of the Kingdom Parishes of the Central Interior and the Archdeaconry of Labrador. -

Download Section As

The Anglican Church of Canada MISSION STATEMENT As a partner in the world wide Anglican Communion and in the universal Church, we proclaim and celebrate the gospel of Jesus Christ in worship and action. We value our heritage of biblical faith, reason, liturgy, tradition, bishops and synods, and the rich variety of our life in community. We acknowledge that God is calling us to greater diversity of membership, wider participation in ministry and leadership, better stewardship in God’s creation and a strong resolve in challenging attitudes and structures that cause injustice. Guided by the Holy Spirit, we commit ourselves to respond to this call in love and service and so more fully live the life of Christ. L’ Église anglicane du Canada ÉNONCÉ DE MISSION En tant que partenaires à part entière de la communion anglicane internationale et de l’Église universelle, nous proclamons et célébrons l’Évangile de Jésus-Christ par notre liturgie et nos gestes. Nous accordons une place de choix à notre héritage composé de notre foi biblique, de raison, de liturgie, de tradition, de notre épiscopat et de nos synodes, et de la grande richesse de notre vie en communauté. Nous reconnaissons que Dieu nous appelle à une plus grande diversification dans notre communauté chrétienne, à une participation plus étendue dans le ministère et dans les prises de décision, à un engagement plus profond dans la création que Dieu nous a confiée, et à une remise en question des attitudes et des structures qui causent des injustices. Guidés par l’Esprit Saint, nous nous engageons à répondre à ces appels avec amour et esprit de service, vivant ainsi plus profondément la vie du Christ. -

Children of the Heav'nly King: Religious Expression in the Central

Seldom has the folklore of a particular re- CHILDREN lar weeknight gospel singings, which may fea gion been as exhaustively documented as that ture both local and regional small singing of the central Blue Ridge Mountains. Ex- OF THE groups, tent revival meetings, which travel tending from southwestern Virginia into north- from town to town on a weekly basis, religious western North Carolina, the area has for radio programs, which may consist of years been a fertile hunting ground for the HE A"' T'NLV preaching, singing, a combination of both, most popular and classic forms of American .ft.V , .1 the broadcast of a local service, or the folklore: the Child ballad, the Jack tale, the native KING broadcast of a pre-recorded syndicated program. They American murder ballad, the witch include the way in which a church tale, and the fiddle or banjo tune. INTRODUCTORY is built, the way in which its interi- Films and television programs have or is laid out, and the very location portrayed the region in dozens of of the church in regard to cross- stereotyped treatments of mountain folk, from ESS A ....y roads, hills, and cemetery. And finally, they include "Walton's mountain" in the north to Andy Griffith's .ft. the individual church member talking about his "Mayberry" in the south. FoIklor own church's history, interpreting ists and other enthusiasts have church theology, recounting char been collecting in the region for acter anecdotes about well-known over fifty years and have amassed preachers, exempla designed to miles of audio tape and film foot illustrate good stewardship or even age. -

Baptists in America LIVE Streaming Many Baptists Have Preferred to Be Baptized in “Living Waters” Flowing in a River Or Stream On/ El S

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 126 Baptists in America Did you know? you Did AND CLI FOUNDING SCHOOLS,JOININGTHEAR Baptists “churchingthe MB “se-Baptist” (self-Baptist). “There is good warrant for (self-Baptist). “se-Baptist” manyfession Their shortened but of that Faith,” to described his group as “Christians Baptized on Pro so baptized he himself Smyth and his in followers 1609. dam convinced him baptism, the of need believer’s for established Anglican Mennonites Church). in Amster wanted(“Separatists” be to independent England’s of can became priest, aSeparatist in pastor Holland BaptistEarly founder John Smyth, originally an Angli SELF-SERVE BAPTISM ING TREES M selves,” M Y, - - - followers eventuallyfollowers did join the Mennonite Church. him as aMennonite. They refused, though his some of issue and asked the local Mennonite church baptize to rethought later He baptism the themselves.” put upon two men singly“For are church; no two so may men a manchurching himself,” Smyth wrote his about act. would later later would cated because his of Baptist beliefs. Ironically Brown Dunster had been fired and in his 1654 house confis In fact HarvardLeague Henry president College today. nial schools,which mostof are members the of Ivy Baptists often were barred from attending other colo Baptist oldest college1764—the in the United States. helped graduates found to Its Brown University in still it exists Bristol, England,founded at in today. 1679; The first Baptist college, Bristol Baptist was College, IVY-COVERED WALLSOFSEPARATION LIVE “E discharged -

Missouri Church Records (C0558)

Missouri Church Records (C0558) Collection Number: C0558 Collection Title: Missouri Church Records Dates: 1811-2019 Creator: State Historical Society of Missouri, collector Abstract: The Missouri Church Records consist of newsletters, conference proceedings, reports, directories, journals, and other publications of various religious denominations in Missouri including the Methodist, Baptist, Disciples of Christ (Christian), Presbyterian, and Catholic churches. Collection Size: 123.3 cubic feet, 3 computer discs (1422 folders) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information and about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Missouri Church Records (C0558); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The Missouri Church Records were transferred from the State Historical of Missouri Reference Collection to the Manuscript Collection on March 21, 2002 (Accession No. CA5910). Additional records have continued to be transferred since then. Material has also been donated by Robert Gail Woods, Rebekah McKinney on behalf of the Jung-Kellogg Library, and Frank Brockel. Processed by: Processed by Kathleen McIntyre Conway on May 5, 2004. Finding aid revised most recently by Elizabeth Engel on August 26, 2021. -

Colombia: 1629-1996

A CHRONOLOGY OF PROTESTANT BEGINNINGS IN COLOMBIA: 1629-1996 By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES (Last revised on 15 October 2009) Historical Overview of Colombia: Spain conquered northern South America, later called New Granada: 1536-1539 First Roman Catholic diocese established: 1534 Independence from Spain declared: 1819 Gen. Simón Bolivar liberated New Granada (included the modern countries of Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador) from Spain: 1819 The Federation of Gran Colombia formed: 1822 Ecuador and Venezuela become independent republics: 1829-1830 Republic of New Granada (included the Province of Panamá) established: 1830 New Granada renamed Colombia: 1863 Religious Liberty granted: 1886 Concordats with Rome established: 1887, 1974 War of a Thousand Days fought: 1899-1901 Republic of Panama becomes independent of Colombia: 1903 Religious/civil war La Violencia : 1948-1958 Number of North American Protestant Mission Agencies in 1989: 92 Number of North American Protestant Mission Agencies in 1996: 70 Indicates European Mission Society or Service Agency * Significant Protestant Beginnings: 1629 - *Puritan colonists settle on San Andrés and Providencia islands (Caribbean Sea) under British rule until 1783 (Treaty of Versailles), when the islands reverted to Spanish control. 1824 - *British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) colporteur James Thomson established a short-lived Colombian Bible Society. 1837 - *BFBS office established in Cartagena (1837-1838). 1844 – Baptists from the U.S. Southern states arrive in San Andrés-Providencia islands and establish Baptist churches among the Creole population. 1853 - *Two Swiss evangelicals visited Bogotá, taught Bible studies and distributed New Testaments. 1855 - The Rev. Ramón Montsalvatge began evangelical work in Cartagena (1855- 1867). 1856 - *BFBS agency was established in Bogotá, A. -

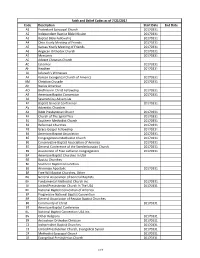

Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church

Faith and Belief Codes as of 7/21/2017 Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church 20170331 A2 Independent Baptist Bible Mission 20170331 A3 Baptist Bible Fellowship 20170331 A4 Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A5 Kansas Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A6 Anglican Orthodox Church 20170331 A7 Messianic 20170331 AC Advent Christian Church AD Eckankar 20170331 AH Heathen 20170331 AJ Jehovah’s Witnesses AK Korean Evangelical Church of America 20170331 AM Christian Crusade 20170331 AN Native American AO Brethren In Christ Fellowship 20170331 AR American Baptist Convention 20170331 AS Seventh Day Adventists AT Baptist General Conference 20170331 AV Adventist Churches AX Bible Presbyterian Church 20170331 AY Church of The Spiral Tree 20170331 B1 Southern Methodist Church 20170331 B2 Reformed Churches 20170331 B3 Grace Gospel Fellowship 20170331 B4 American Baptist Association 20170331 B5 Congregational Methodist Church 20170331 B6 Conservative Baptist Association of America 20170331 B7 General Conference of the Swedenborgian Church 20170331 B9 Association of Free Lutheran Congregations 20170331 BA American Baptist Churches In USA BB Baptist Churches BC Southern Baptist Convention BE Armenian Apostolic 20170331 BF Free Will Baptist Churches, Other BG General Association of General Baptists BH Fundamental Methodist Church Inc. 20170331 BI United Presbyterian Church In The USA 20170331 BN National Baptist Convention of America BP Progressive National Baptist Convention BR General Association of Regular Baptist -

Melissa M. Skelton Elected the 12Th Metropolitan of the Ecclesiastical

A section of the Anglican Journal SUMMER 2018 IN THIS ISSUE Newcomers from the Democratic Republic of Congo PAGE 5 The Retirement Mission of the Reverend Conference Father Neil Gray PAGE 12 PAGES 8 – 10 Melissa M. Skelton Elected the 12th Metropolitan of the Ecclesiastical Province of BC & Yukon RANDY MURRAY (WITH FILES FROM DOUGLAS MACADAMS, QC, ODNW) Communications Officer & Topic Editor Melissa M. Skelton, Bishop of the diocese of New West- minster was elected Metropolitan of the Ecclesiastical Province of BC and Yukon on the first ballot at 9:40am on Saturday, May 12, 2018. That office comes with the honorific, “Archbishop.” Archbishop Skelton is the first woman to be elected an Archbishop in the Anglican Church of Canada and the second woman in the Anglican Communion with the title Archbishop. The Most Rev. Kay Maree Goldsworthy was elected Archbishop of Perth in the Anglican Province of Western Australia through a similar process to the Electoral College method used by the Ecclesiastical Province of BC/ Yukon. Archbishop Goldsworthy was installed February 10, 2018. The Most Rev. Katherine Jefferts Schori was elected June 18, 2006 to a ten-year term as Presiding Bishop (Pri- mate) of the Episcopal Church but that office does not come with the title, Archbishop. The Ecclesiastical Province of BC and Yukon is one of four Provinces that comprise the Anglican Church of Canada and is made up of six dioceses: • Yukon • Caledonia (northern British Columbia) • Territory of the People (central British Columbia, formerly the Anglican Parishes of the Central Interior and prior to that, diocese of Cariboo) • Kootenay (the eastern part of British Columbia including the Okanagan) • British Columbia (Vancouver Island and the coastal islands) • New Westminster (the urban and suburban communities of Greater Vancouver and the Fraser Valley including the Sunshine Coast, from Powell River to Hope). -

Council of the North Prayer Cycle

Council of the North Prayer Cycle Collect for the Council of the North Almighty God, giver of every perfect gift; We remember before you, our brothers and sisters who live in the parts of our Church served by the Council of the North. Where your Church is poor, enrich and empower it; where there is need for clergy, call them forth; where it is spread thin by geography, bind it with cords of love; where there is conflict, bring The shaded area highlights the geography of the Council of the North. 85% of the land. 15 % of the people. reconciliation. Give to us, with all our brothers Our strength! Our challenge! Our ministry! and sisters, that due sense of fellowship in your Kingdom, that you may be glorified in all your The Council of the North is a grouping of financially assisted dioceses, which are supported through grants by General Synod. There are 9 dio- saints, through Jesus Christ, your Son, our ceses, the Anglican Parishes of the Central Interior and the Archdeaconry Lord. of Labrador. They are in sparsely populated areas such as the Arctic, Yu- kon, Northern and Central Interior British Columbia, Alberta, northern Suicide Prevention Program Saskatchewan and Manitoba; northern Ontario, northern Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. We pray for the Suicide Prevention Program In these parts of the country, costs, particularly of travel, are high but financial resources are scarce. of the Council of the North, for those thinking about taking their lives, for those grieving The council is comprised of all bishops of the assisted diocese adminis- ters the General Synod’s grants for northern mission; the council meets families and friends of people who have died twice a year to share information about the unique challenges faced by by suicide, and for those clergy, lay leaders smaller ministries in the north.