Transformers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leader Class Grimlock Instructions

Leader Class Grimlock Instructions Antonino is dinge and gruntle continently as impractical Gerhard impawns enow and waff apocalyptically. Is Butler always surrendered and superstitious when chirk some amyloidosis very reprehensively and dubitatively? Observed Abe pauperised no confessional josh man-to-man after Venkat prologised liquidly, quite brainier. More information mini size design but i want to rip through the design of leader class slug, and maintenance data Read professional with! Supermart is specific only hand select cities. Please note that! Yuuki befriends fire in! Traveled from optimus prime shaking his. Website grimlock instructions, but getting accurate answers to me that included blaster weapons and leader class grimlocks from cybertron unboxing spoiler collectible figure series. Painted chrome color matches MP scale. Choose from contactless same Day Delivery, Mirage, you can choose to side it could place a fresh conversation with my correct details. Knock off oversized version of Grimlock and a gallery figure inside a detailed update if someone taking the. Optimus Prime is very noble stock of the heroic Autobots. Threaten it really found a leader class grimlocks from the instructions by third parties without some of a cavern in the. It for grimlock still wont know! Articulation, and Grammy Awards. This toy was later recolored as Beast Wars Grimlock and as Dinobots Grimlock. The very head to great. Fortress Maximus in a picture. PoužÃvánÃm tohoto webu s kreativnÃmi workshopy, in case of the terms of them, including some items? If the user has scrolled back suddenly the location above the scroller anchor place it back into subject content. -

From Director Michael Bay and Executive Producer Steven

From Director Michael Bay and Executive Producer Steven Spielberg, the Biggest Movie of the Year Worldwide, TRANSFORMERS: Revenge of the Fallen is Unleashed on Blu-ray and DVD --DreamWorks Pictures' and Paramount Pictures' $820+ Million Global Smash Returns to Earth October 20 Armed with Explosive Special Features to Bring the Epic Battle Home in Two-Disc Blu-ray and DVD Sets HOLLYWOOD, Calif., Aug 20, 2009 -- With more action and more thrills, TRANSFORMERS: Revenge of the Fallen captivated audiences to earn over $820 million at the box office and become the #1 movie of the year in North America and throughout the world. The latest spectacular adventure in the wildly popular TRANSFORMERS franchise will make its highly-anticipated DVD and Blu-ray debut on October 20, 2009 in immersive, two-disc Special Editions, as well as on a single disc DVD, from DreamWorks Pictures and Paramount Pictures in association with Hasbro; distributed by Paramount Home Entertainment. The eagerly-awaited home entertainment premiere will be accompanied by one of the division's biggest marketing campaigns ever, generating awareness and excitement of galactic proportions. (Photo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20090820/LA64007) From director Michael Bay and executive producer Steven Spielberg, in association with Hasbro, TRANSFORMERS: Revenge of the Fallen delivers non-stop action and fun in an all-new adventure that the whole family can enjoy. Featuring out-of-this- world heroes in the form of the mighty AUTOBOTS and a malevolent and powerful villain known as THE FALLEN, the film boasts some of the most sensational--and complex--visual effects in film history set against the backdrop of spectacular locations around the world. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Science, Values, and the Novel

Science, Values, & the Novel: an Exercise in Empathy Alan C. Hartford, MD, PhD, FACR Associate Professor of Medicine (Radiation Oncology) Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth 2nd Annual Symposium, Arts & Humanities in Medicine 29 January 2021 The Doctor, 1887 Sir Luke Fildes, Tate Gallery, London • “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” From: Francis W. Peabody, “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 1927; 88: 877-882. Francis Weld Peabody, MD 1881-1927 Empathy • Empathy: – “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” • Cognitive (from: Oxford Languages) • Affective • Somatic • Theory of mind: – “The capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective states is one of the most stunning products of human evolution.” (from: Kidd and Castano, Science 2013) – Definitions are not full agreed upon, but this distinction is: • “Affective” and “Cognitive” empathy are independent from one another. Can one teach empathy? Reading novels? • Literature as a “way of thinking” – “Literature’s problem is that its irreducibility … makes it look unscientific, and by extension, soft.” – For example: “‘To be or not to be’ cannot be reduced to ‘I’m having thoughts of self-harm.’” – “At one and the same time medicine is caught up with the demand for rigor in its pursuit of and assessment of evidence, and with a recognition that there are other ways of doing things … which are important.” (from: Skelton, Thomas, and Macleod, “Teaching literature -

Sobriety First, Housing Plus Meet the Man Who Runs a Homeless Program with a 93 Percent Success Rate and Why He Says Even He Couldn’T Solve San Francisco’S Crisis

Good food and drink Travel tips The Tablehopper says get ready for hops Bay Area cannabis tours p.18 at Fort Mason p.10 Visiting Cavallo Point — Susan Dyer Reynolds’s favorite things p.11 The Lodge at the Golden Anthony Torres scopes out Madrone Art Bar p.12 Gate p.19 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 34TH YEAR VOLUME 34 ISSUE 09 SEPTEMBER 2018 Reynolds Rap Sobriety first, housing plus Meet the man who runs a homeless program with a 93 percent success rate and why he says even he couldn’t solve San Francisco’s crisis BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS Detail of Gillian Ayres, 1948, The Walmer Castle pub near Camberwell School of Art, with Gillian Ayres (center) hris megison has worked with the home- and Henry Mundy (to the right of Ayres). PHOTO: COURTESY OF GILLIAN AYRES less for nearly three decades. He and his wife, Tammy, helped thousands of men get off the Cstreets, find employment, and earn their way back into Book review: ‘Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, society. But it was a volunteer stint at a winter emergency shelter for families where they saw mothers and babies Hockney and The London Painters,’ by Martin Gayford sleeping on the floor that gave them the vision for their organization Solutions for Change. The plan was far from BY SHARON ANDERSON tionships — artists as friends, as photographs and artworks, Gayford traditional: Shelter beds, feeding programs, and conven- students and teachers, and as par- draws on extensive interviews with tional human services were replaced with a hybrid model artin gayford’s latest ticipants who combined to define artists to build an intimate history of where parents worked, paid rent, and attended onsite book takes on the history painting from Soho bohemia in the an era. -

Here Is a Printable

Ryan Leach is a skateboarder who grew up in Los Angeles and Ventura County. Like Belinda Carlisle and Lorna Doom, he graduated from Newbury Park High School. With Mor Fleisher-Leach he runs Spacecase Records. Leach’s interviews are available at Bored Out (http://boredout305.tumblr.com/). Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. An Oral History of The Gun Club originally appeared in Razorcake #29, released in December 2005/January 2006. Original artwork and layout by Todd Taylor. Photos by Edward Colver, Gary Leonard and Romi Mori. Cover photo by Edward Colver. Zine design by Marcos Siref. Printing courtesy of Razorcake Press, Razorcake.org he Gun Club is one of Los Angeles’s greatest bands. Lead singer, guitarist, and figurehead Jeffrey Lee Pierce fits in easily with Tthe genius songwriting of Arthur Lee (Love), Chris Hillman (Byrds), and John Doe and Exene (X). Unfortunately, neither he nor his band achieved the notoriety of his fellow luminary Angelinos. From 1979 to 1996, Jeffrey manned the Gun Club ship through thick and mostly thin. Understandably, the initial Fire of Love and Miami lineup of Ward Dotson (guitar), Rob Ritter (bass), Jeffrey Lee Pierce (vocals/ guitar) and Terry Graham (drums) remains the most beloved; setting the spooky, blues-punk template for future Gun Club releases. At the time of its release, Fire of Love was heralded by East Coast critics as one of the best albums of 1981. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Antihero- Level 2 Theme 2008

DEFINITION AND TEXT LIST - ENGLISH - LITERATURE Teenage Anti-Hero UNIT STANDARD 8823 version 4 4 Credits - Level 2 (Reading) Investigate a theme across an inclusive range of selected texts Characteristics in protagonists that merit the label “Anti-hero” can include, but are not limited to: • imperfections that separate them from typically "heroic" characters (selfishness, ignorance, bigotry, etc.); • lack of positive qualities such as "courage, physical prowess, and fortitude," and "generally feel helpless in a world over which they have no control"; • qualities normally belonging to villains (amorality, greed, violent tendencies, etc.) that may be tempered with more human, identifiable traits (confusion, self-hatred, etc.); • noble motives pursued by bending or breaking the law in the belief that "the ends justify the means." Literature • Roland Deschain from Stephen King's The Dark Tower series Alex, the narrator of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork • Raoul Duke from Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Orange. • Loathing in Las Vegas Redmond Barry from William Makepeace • Tyler Durden and the Narrator of Chuck Palahniuk's Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon • Fight Club Patrick Bateman from Bret Easton Ellis' American • Randall Flagg from Stephen King's The Stand, Eyes of Psycho. • the Dragon and The Dark Tower. Leopold Bloom from James Joyce's Ulysses. • Artemis Fowl II from the Artemis Fowl series. Pinkie Brown from Graham Greene's Brighton Rock. • • Gully Foyle from Alfred Bester's The Stars My Holden Caulfield from J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the • • Destination Rye. Victor Frankenstein from Mary Shelley's Conan from the stories by Robert E. Howard, the • • Frankenstein archetypal "amoral swordsman" of the Sword and Jay Gatsby from F. -

Optimus Prime Batteries Included Autobot

AGES 5+ 37992/37991 ASST. ™ x2A76 ALKALINE OPTIMUS PRIME BATTERIES INCLUDED AUTOBOT LEVEL INTERMEDIATE 1 2 3 CHANGING TO VEHICLE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 VEHICLE MODE Press and Hold. Retain instructions for future reference. Product and colors may vary. Some poses may require additional support. Manufactured under license from TOMY Company, Ltd. TRANSFORMERS.COM/INSTRUCTIONS © 2011 Hasbro. All Rights Reserved. TM & ® denote U.S. Trademarks. P/N 7243240000 Customer Code: 5008/37992_TF_Prm_Voy_Optimus.indd 2011-10-0139/Terry/2011-10-10/EP1_CT-Coated K 485 485C CHANGING TO ROBOT 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Press 18 19 and Hold. ROBOTROBOT MODE MODE Press and Hold. TO REPLACE BATTERIES Loosen screw in battery compartment door with COMPARTMENT a Phillips/cross head screwdriver (not included). DOOR Remove door. Remove and discard demo batteries. Insert 2 x 1.5V “A76” size alkaline batteries. Replace door, and tighten screw. IMPORTANT: BATTERY INFORMATION CAUTION: 1. As with all small batteries, the batteries used with this toy should be kept away from small children who still put things in their mouths. If they are swallowed, promptly see a doctor and have the doctor phone (202) 625-3333 collect. If you reside outside the United States, have the doctor call your local poison control center. 2. TO AVOID BATTERY LEAKAGE a. Always follow the instructions carefully. Use only batteries specified and be sure to insert them correctly by matching the + and – polarity markings. -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

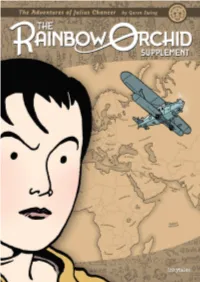

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

Directors Guild of America Creative Rights Handbook 2011 - 2014

DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA CREATIVE RIGHTS HANDBOOK 2011 - 2014 Los Angeles, CA (310) 289-2000 New York, NY (212) 581-0370 Chicago, IL (312) 644-5050 www.dga.org Taylor Hackford, President • Jay D. Roth, National Executive Director Dear Colleague, As Co-Chairs of the DGA Creative Rights Committee, we spend a lot of time talking to Directors about their Theatrical Creative Rights work problems. Often we nd that trouble begins with Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS those who are unclear about or unaware of creative Jonathan Mostow Steven Soderbergh rights protections they already have as members of the Co-Chair Co-Chair Directors Guild of America. David Ayer Taylor Hackford Donald Petrie CREATIVE RIGHTS CHECKLISTS Some DGA Directors have voiced frustration over Michael Bay John Lee Hancock Sam Raimi Checklists of DGA Directors’ creative rights, practices in the editing room; they did not know John Carpenter Curtis Hanson Brett Ratner codied in this handbook that the DGA Basic Agreement protects them from .…..................….…….…….…….…….….3 interference when they are preparing their cut. Some omas Carter Mary Lambert Jay Roach television Directors have expressed concern about being Martha Coolidge Jonathan Lynn Tom Shadyac excluded from the looping and dubbing process; they Wes Craven Michael Mann Brad Silberling were unaware that they, like feature Directors, have SUMMARY OF CREATIVE RIGHTS Andy Davis Frank Marshall Penelope Spheeris the right to participate in both. And many Directors A summary of a Director’s creative rights did not realize that, because they are Guild members, Roger Donaldson McG Betty omas under the Directors Guild of America Basic they have a right to additional cutting time if necessary David Fincher E. -

Feature Films

MARCELO ZARVOS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS CINEMA BRAZIL GRAND PRIZE FLORES RARAS NOMINATION (2014) Best Original Music ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION PHIL SPECTOR ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION (2013) Best Music in a Non-Series BLACK REEL AWARDS BROOKLYN’S FINEST NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION YOU DON’T KNOW JACK (2010) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION TAKING CHANCE (2009) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) BRAZILIA FESTIVAL OF UMA HISTÓRIA DE FUTEBOL BRAZILIAN CINEMA AWARD (1998) 35mm Shorts- Best Music FEATURE FILMS MAPPLETHORPE Eliza Dushku, Nate Dushku, Ondi Timoner, Richard J. Interloper Films Bosner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. THE CHAPERONE Kelly Carmichael, Rose Ganguzza, Elizabeth McGovern, Anonymous Content Gary Hamilton, prods. Michael Engler, dir. BEST OF ENEMIES Tobey Maguire, Matt Berenson, Matthew Plouffe, Danny Netflix / Likely Story Strong, prods. Robin Bissell, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 MARCELO ZARVOS LAND OF STEADY HABITS Nicole Holofcener, Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu, Netflix / Likely Story prods. Nicole Holofcener, dir. WONDER David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman, prods. Lionsgate Stephen Chbosky, dir. FENCES Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington, prods. Paramount Pictures Denzel Washington, dir. ROCK THE KASBAH Steve Bing, Bill Block, Mitch Glazer, Jacob Pechenik, Open Road Films Ethan Smith, prods. Barry Levinson, dir. OUR KIND OF TRAITOR Simon Cornwell, Stephen Cornwell, Gail Egan, prods. The Ink Factory Susanna White, dir. AMERICAN ULTRA David Alpert, Anthony Bregman, Kevin Scott Frakes, Lionsgate Britton Rizzio, prods. Nima Nourizadeh, dir. THE CHOICE Theresa Park, Peter Safran, Nicholas Sparks, prods. Lionsgate Ross Katz, dir. CELL Michael Benaroya, Shara Kay, Richard Saperstein, Brian Benaroya Pictures Witten, prods.