A Railway Flora of Rutland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land and Buildings at Morcott, Wing Road, Morcott, Rutland

Land and buildings at Morcott, Wing Road, Morcott, Rutland Land and buildings The market towns of Uppingham and Oakham provide every day amenities, with further facilities at Morcott in Stamford or Peterborough. Schooling in Wing Road, Morcott, Rutland the area is excellent at Uppingham, Oakham and Stamford. A parcel of rolling arable land Land and buildings at Morcott with attractive stone buildings Extending to about 125.36 acres in total, the property provides an opportunity to acquire a benefitting from consent for picturesque parcel of productive arable land conversion. in the heart of Rutland with an outstanding set of stone buildings with planning consent for conversion. Grade 3 arable land | Beautiful stone barn and buildings with consent for conversion Lot 1 – Stone barn and outbuildings Land with road frontage and outstanding About 3.52 acres (1.42ha) views over Rutland A range of stone buildings with the benefit of Uppingham 4 miles, Stamford 8.5 miles, permitted development rights for conversion of Peterborough 18 miles conversion 2,142 sq ft into a dwelling together with about 3.52 acres of land. The consent About 125.36 acres (50.73 ha) in total permits conversion of the two storey stone barn Available for sale as a whole or in two lots into a three bedroom dwelling which would comprise a kitchen, living room, utility, WC and Lot 1 – Stone barn and outbuildings hall, bedroom and shower room, two further About 3.52 acres (1.42ha) bedrooms and a family bathroom. There is a Consent for a three bedroom dwelling | Further further outbuilding connected to the main barn outbuilding with potential for conversion which could be converted subject to obtaining Agricultural land planning permission. -

New Joiner Information 2020

SCHOOL BUS SERVICE 2020-21 Services operate from Monday to Friday in term time. Route 4 and Route 5 include Saturday mornings. Routes 1: Foxton, 2: Tur Langton and 3: Market Harborough operated through A&S coaches, www.aandscoaches.com Routes 4: Stamford or 5: Balderton run by Oakham School minibus fleet. Pick-up points, times and fares are below. Fares 2020-21 Day Pupils Flexi/Transitional When booking please specify Termly fares 10 journeys a week Boarders whether you are booking for Routes 1, 2 and 3 £565 £480 a Day pupil or a Flexi / Route 4 £370 £315 Transitional boarder. Route 5 £595 £515 Pick-up Points and Times Route 1 Foxton – Kibworth – Tilton-on-the-Hill – Oakham Morning Evening Mon & Fri Tues & Wed Thurs Foxton 07.15 Oakham 18.10 17.00 17.15 Kibworth 07.20 Tilton-on-the-Hill 18.30 17.20 17.35 Tilton-on-the-Hill 07.40 Foxton 18.55 17.45 18.00 Oakham 08.05 Kibworth Drop 1 19.03 17.52 18.07 Kibworth Drop 2 19:05 17:55 18:10 Pick up points Foxton Swing Bridge Street on the corner of Hogg Lane Kibworth Morning: large lay-by on the A6 Evening: Drop 1: large lay-by on the A6, Drop 2: near The Swan Tilton-on-the-Hill Shop/Post Office on Oakham Road Route 2 Leicester – Oadby – Kibworth – Tur Langton – Billesdon – Oakham Morning Evening Mon & Fri Tues & Wed Thurs Leicester 07:00 Oakham 18.05 17.00 17.15 Oadby 07:10 Billesdon 18.30 17.25 17.40 Kibworth 07:20 Tur Langton 18.40 17.35 17.50 Tur Langton 07.30 Kibworth 18:50 17:45 18:00 Billesdon 07.40 Oadby 19:05 17.55 18:10 Oakham 08.05 Leicester 19:15 18:05 18.20 Pick up points Leicester Train Station, London Road Oadby Morning: Esso fuel station Bus stop. -

Great Casterton Parish Plan 2005

A1 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Rutland Council District Council Licence No. LA 100018056 With Special thanks to: 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. History 3. Community and household 4. Transport and traffic 5. Crime and community safety 6. Sport and leisure 7. Youth 8. Village church 9. Education 10. Retail services 11. Farming and heritage 12. Conservation and the environment 13. Planning and development 14. Health and social services 15. Information and communication 16. Local councils 17. Conclusion 18. Action plan 3 INTRODUCTION PARISH PLANS Parish plans are part of the “Vital Villages” initiative of the Countryside Agency, run locally through the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland). A Parish Plan should provide a picture of a village, identifying through consultation the concerns and needs of its residents. From the plan villages should identify actions to improve the village and the life of the community. The resulting Village Action Plan is then used to inform the County Council, through the Parish Council. Parish Plans have a statutory place in local government. GREAT CASTERTON PARISH PLAN Great Casterton’s Parish Plan started with a meeting of villagers in June 2002. There was particular interest because of a contentious planning decision imposed by the County Council on the village. The Community Development Officer for Rutland, Adele Stainsby, explained the purpose of the plan and the benefits for the village. A committee was formed, and a constitution drawn up. The Parish Council promised a small initial grant while an application for Countryside Agency funding was prepared. The money granted was to be balanced by the voluntary work of villagers. -

RISE up STAND out This Guide Should Cover What You Need to Know Before You Apply, but It Won’T Cover Everything About College

RISE UP STAND OUT This guide should cover what you need to know before you apply, but it won’t cover everything about College. We 2020-21 WELCOME TO know that sometimes you can’t beat speaking to a helpful member of the VIRTUAL team about your concerns. OPEN Whether you aren’t sure about your bus EVENTS STAMFORD route, where to sit and have lunch or want to meet the tutors and ask about your course, you can Live Chat, call or 14 Oct 2020 email us to get your questions answered. COLLEGE 4 Nov 2020 Remember, just because you can’t visit 25 Nov 2020 us, it doesn’t mean you can’t meet us! 20 Jan 2021 Find out more about our virtual open events on our website. Contents Our Promise To You ..............................4 Childcare ....................................................66 Careers Reference ................................. 6 Computing & IT..................................... 70 Facilities ........................................................ 8 Construction ............................................74 Life on Campus ...................................... 10 Creative Arts ...........................................80 Student Support ....................................12 Hair & Beauty ......................................... 86 Financial Support ................................. 14 Health & Social Care .......................... 90 Advice For Parents ...............................16 Media ........................................................... 94 Guide to Course Levels ......................18 Motor Vehicle ........................................ -

East Midlands Derby

Archaeological Investigations Project 2007 Post-determination & Research Version 4.1 East Midlands Derby Derby UA (E.56.2242) SK39503370 AIP database ID: {5599D385-6067-4333-8E9E-46619CFE138A} Parish: Alvaston Ward Postal Code: DE24 0YZ GREEN LANE Archaeological Watching Brief on Geotechnical Trial Holes at Green Lane, Derbyshire McCoy, M Sheffield : ARCUS, 2007, 18pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: ARCUS There were no known earthworks or findspots within the vicinity of the site, but traces of medieval ridge and furrow survived in the woodlands bordering the northern limits of the proposed development area. Despite this, no archaeological remains were encountered during the watching brief. [Au(adp)] OASIS ID :no (E.56.2243) SK34733633 AIP database ID: {B93D02C0-8E2B-491C-8C5F-C19BD4C17BC7} Parish: Arboretum Ward Postal Code: DE1 1FH STAFFORD STREET, DERBY Stafford Street, Derby. Report on a Watching Brief Undertaken in Advance of Construction Works Marshall, B Bakewell : Archaeological Research Services, 2007, 16pp, colour pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Research Services No archaeological remains were encountered during the watching brief. [Au(adp)] OASIS ID :no (E.56.2244) SK35503850 AIP database ID: {5F636C88-F246-4474-ABF7-6CB476918678} Parish: Darley Ward Postal Code: DE22 1EB DARLEY ABBEY PUMP HOUSE, DERBY Darley Abbey Pump House, Derby. Results of an Archaeological Watching Brief Shakarian, J Bakewell : Archaeological Research Services, 2007, 14pp, colour pls, figs, refs, CD Work undertaken -

Welland View Glaston Road | Uppingham | Rutland | LE15 9EU WELLAND VIEW

Welland View Glaston Road | Uppingham | Rutland | LE15 9EU WELLAND VIEW • Established Family Home in Private Position on the Outskirts of Uppingham • Offering Much Improved Spacious and Well Maintained Accommodation Throughout • Sitting Room, Library, Office, L-Shaped Kitchen / Dining Room • Master Bedroom Suite Comprising Dressing Room, Walk-in Wardrobe & En Suite • Three Further Double Bedrooms and Family Bathroom • Self-Contained Annex with Sitting Room, Kitchen, Two Bedrooms & Bathroom • Total Plot of Circa 3/4 acre with Mature Landscaped Gardens • Double Garage with Ample Off-Road Parking for a Number of Vehicles • Selection of Outbuildings Including Garaging, Workshop and Garden Store • Total Accommodation Excluding Outbuildings Extends to 2997 Sq.Ft. Within a seven minute walk of the charming town of Uppingham in Rutland, stands an attractive home originally from the seventies, which has been completely renovated, almost rebuilt, in recent years and has become the most perfect family home. Welland View sits on a private and tranquil plot of nearly an acre enclosed by mature trees. It not only has three to four bedrooms in the main part of the house, but two further bedrooms in the adjoining annex, with even more potential for conversion of the garaging and workshops (subject to planning). Approached from a quiet road linking the town with the A47, Welland Views’ entrance is off a shared drive with a pretty and small, independent garden centre, providing a number of benefits. “If I had a choice of who to have as a neighbour,” divulges the owner, “ I would choose a garden centre. We rarely hear any noise from there, and my mother-in-law loves visiting it when she comes to stay! As they shut at five, we can have a noisy party and not need to worry. -

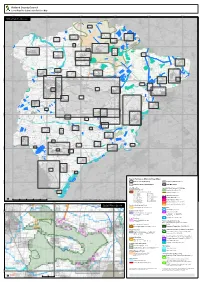

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

Uppingham Every Wednesday

1281 Jun 5 Fair granted on the Feast of St. Margaret the Virgin and morrow. 1281 Jun 5 Market granted to Uppingham every Wednesday. 1335 May 26 The two mother churches of Uppingham & Werlea and the & 18 Edw houses of Wilfuninus the priest and all thereto belonging, III granted by Edward the Confessor to the Abbey Church of Westminster on 28 December 1066 (examined). 1374 ND 1. On Thursday after St. Michael 48 Edw 3, Beatrix Skinner is charged that on Monday after St Gregory 44 Edw 3 she stole from William of Rockingham at Uppingham one bushel of barley worth 12d and ½ bushel of oats worth 3d. Verdict, not guilty. 2. Also Alicia daughter of Thomas Bene of Uppingham is charged that on Tuesday after the Conversion of St Paul 38 Edw III, she stole 5 geese & 4 hens worth 40d from John o’ the Greene and others serving William de Rockingham, at Uppingham. Verdict, not guilty. 1484 Feb 17 John Gardener of Barkeby with others unknown on the Thursday next after St Valentine 2 Ric III, came to the house of Thomas Saddler of Uppingham and broke his doors & stole one knife worth 2d. 1489 ND Chapel of SS Trinity, Uppingham. 1489 ND Linc Wills ref Wolsey, Atwater 1521 ND Sir Henry Atkinson, Curate of Uppingham. 1523 ND Sir Henry Parkinson, parish priest of Uppingham. 1526 ND Randolf Greene of Uppingham pardoned for the murder of iv.2132 John Mickal. 1538 ND The same Thomas More not paying 20s for a levy made towards the repair of the organ there. -

219832 the Old Plough.Indd

AN ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED DETACHED DWELLING IN A PRIVATE VILLAGE SETTING, WITH THREE ANCILLARY STONE BARNS AND LANDSCAPED GARDENS the old plough, church street, carlby, stamford, lincolnshire, pe9 4nb AN ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED DETACHED DWELLING IN A PRIVATE VILLAGE SETTING, WITH THREE ANCILLARY STONE BARNS AND LANDSCAPED GARDENS the old plough, church street, carlby, stamford, lincolnshire, pe9 4nb Entrance hallway w Sitting room w Dining Kitchen w Study/Play room w Utility w Principal bedroom with en suite w Three further bedrooms w Family bathroom w Driveway & extensive parking w Three ancillary stone barns w Landscaped private gardens Mileage Stamford 6 miles (Trains to Peterborough from 10 mins and Cambridge from 65 mins) w Bourne & Market Deeping 7 miles w Peterborough Railway Station 15 miles (London Kings Cross from 49 mins) Situation Carlby is an attractive small village with a supportive village community, served by Ryhall Primary School, a village with which it often twins for community events. Almost midway between Stamford and Bourne amidst attractive rolling countryside, whilst rural, the village is well connected. The attractive Georgian market towns of Stamford, Bourne and Market Deeping are all within 7 miles of Carlby. For commuters, Stamford’s railway station has hourly train services to Peterborough (connecting to London Kings Cross services) and Cambridge on the Midlands Cross Country Birmingham Airport to Stansted Airport line. Further, the Cathedral City of Peterborough (15 miles) offers a wider range of retail outlets, including the Queensgate Shopping Centre and mainline commuter services to London Kings Cross. Schooling is also well catered for in the area with a choice of private schooling, aside from good state education in Ryhall. -

Courtyard House Harringworth Functional Sophistication

COURTYARD HOUSE HARRINGWORTH FUNCTIONAL SOPHISTICATION Hang up your coat in the cupboard and advance into the oldest part of the home – the sitting room. Here, deep-set windows give nod to the thick stone walls noticeable throughout, ensuring excellent insulation. The gorgeous inglenook fireplace with sturdy beam above houses a cosy wood-burning stove – where better to snuggle up together? Other delightful features in this room come in the form of recessed shelving crowned with an original beam and exposed stone and brickwork, further painted beams, and French doors to tempt you out outside. A WARM To the left, a door continues into a dual aspect study or home office with wooden flooring and WELCOME lots of natural light – creating a lovely, peaceful spot to work or study from home. Arriving at the home, you will find ample parking on the driveway or pull into your double garage. Open the pretty arched gate to reveal a beautiful Indian stone courtyard terrace with A stone’s throw from the Welland Viaduct, in the charming and quiet conservation outdoor lighting and your first glimpse village of Harringworth, stands Courtyard House. Originally a thatched cottage dating of the historic viaduct. On entering the home, you are immediately back to the 1800s, and tastefully extended during the 20th Century, this chain-free, welcomed by a light hallway which stone-built detached home exudes character while attaining a modern flow perfect features an attractive staircase with for entertaining and day-to-day living. Benefiting from four double bedrooms, four two side-aspect windows flooding the reception rooms, detached double garage and a beautiful garden with viaduct views, area below with light, inviting you to unwind as soon as you step past the Courtyard House is waiting for you to call it home. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Welland Valley Route Market Harborough to Peterborough Feasibility Study

Welland Valley Route Market Harborough to Peterborough feasibility study Draft March 2014 Table of contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction and Background Sustrans makes smarter travel choices possible, desirable and inevitable. We’re 2 Route Description a leading UK charity enabling people to travel by foot, bike or public transport for 3 Alternative Route more of the journeys we make every day. We work with families, communities, policy- 4 Route Design makers and partner organisations so that people are able to choose healthier, cleaner 5 Ecology and cheaper journeys, with better places 6 Summary and spaces to move through and live in. It’s time we all began making smarter travel choices. Make your move and support Appendix A – Land Ownership Sustrans today. www.sustrans.org.uk Head Office Sustrans 2 Cathedral Square College Green Bristol - Binding Margin - BS1 5DD Registered Charity No. 326550 (England and Wales) SC039263 (Scotland) VAT Registration No. 416740656 Contains map data (c) www.openstreetmap.org (and) contributors, licence CC-BY-SA (www.creativecommons.org) REPORT INTENDED TO BE PRINTED IN FULL COLOUR ON A3 SIZE PAPER Page 2 l Welland Valley Route, Market Harborough to Peterborough Feasibility Study Welland Valley Railway Path Exisinting National Cycle Network minor road routes Executive summary the key constraint along most of the route. The exception to this is where the line of the railway This report represents the findings of a study to has been broken by the removal of bridges at examine proposals to introduce a cycle route crossing points of roads or water courses. A along the line of the former London Midland final physical constraint (two locations) occurs Scottish Railway from Market Harborough to where the track bed under road bridges has Peterborough.