PROPOSAL Nlaka'pamux Survey of Traditional Cultural Sites in Upper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

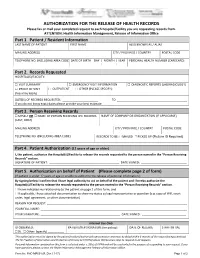

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in Co-Operation with the British Columbia Historical Association

1 THE BRITISH 3_’ .- COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY rI 2 : APRIL, 1938 ,, BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in co-operation with the British Columbia Historical Association. EDITOR. -. :‘“ ;: W. KAYE LAMB. ADVISORY BOARD. J. C. Goom”uLLow, Princeton. F. W. HOWAY, New Westminster. Ronxn L. REiD, Vancouver. T. A. RICKARD, Victoria. W. N. SAGE, Vancouver. Editorial communications should be addressed to the Editor, Provincial Archives, Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. Subscriptions should be sent to the Provincial Archives, Parliament Build ings, Victoria, B.C. Price, 50e. the copy, or $2 the year. Members of the 4. British Columbia Historical Association in good standing receive the Quarterly without further charge. Neither the Provincial Archives nor the British Columbia Historical Association assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors to the magazine. We BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY “Any country worthy of a future should be interested in its past.” VOL. II. VICTORIA, B.C., APRIL, 1938. No. 2 CONTENTS. ARTICLES: PAGE. Fur and Gold in Similkameen. ByJ. C. GOODFELLOW 67 In Memory of David Douglas. ByJORN GOLDIE 89 Early Lumbering on Vancouver Island. Part II.: 1855—1866. ByW.KAYELAM& 95 DOCUMENTS: Coal from the Northwest Coast, 1848—1850. By JOHN HASKELL KEMBLE 123 Sir George Simpson at the Department of State. ByFRANKE.R0ss 131 NOTES AND COMMENTS: — Contributors to this Issue — — 137 Date of Publication — — — 137 British Columbia Historical Association 137 Local Historical Societies 139 Historical Association Reports ___ 141 Hudson’s Bay Record Society 142 65 FUR AND GOLD IN SIMILKAMEEN. Fur-traders pioneered Similkameen before men were at tracted thither by reports of rich placer deposits. -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

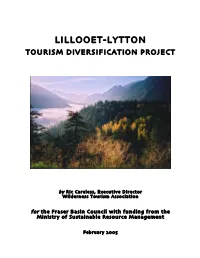

Lillooet-Lytton Tourism Diversification Project

LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM PROJECT 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ..................................................................................4 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Terms of Reference............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Study Area Description...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Local Economic Challenges............................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TOURISM.....................................................................9 2.1 Tourism in British Columbia............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Nature-Based Tourism and Rural BC............................................................................................................ -

An Historic Chinese Camp Near Lytton

Wok Fragments, OpiumTins, and Rock-Walled Structures: An Historic Chinese Camp near Lytton Bill Angelbeck and Dave Hall During a recent archaeological impact assessment of a numerous short-term camping locations associated with travels proposed run-of-river hydroelectric project on Kwoiek Creek up and down the Kwoiek Creek valley, fishing camps along the just south of Lytton, we had the opportunity to record an unusual banks of the Fraser River, and possibly, external activity areas Chinese camp containing II oval-shaped, rock-walled structures. associated with the large pithouse villages located on the high The occupants of the camp had set up the camp within a large terraces both north and south of the confluence ofKwoiek Creek boulder field on a portion of the large alluvial fan located at the and the Fraser River (Angelbeck and Hall 2008). An isolated mouth ofKwoiek Creek. The walls exhibited careful selection of housepit is also present at the site. It is located approximately appropriate rock shapes and tight construction, which in part, is 100 metres east of the rock-walled structures closer to the ter why these walls still stand to this day (Figure I). Rodney Garcia race edge that drops sharply down to the Fraser River (Figure and Tim Spinks ofthe Kanaka Bar Indian Band had Jed us to these 2). Another isolated pithouse was also identified to the west structures during our archaeological survey of the Kwoiek Creek of the site, further up the Kwoiek Creek valley. During our Valley. A wok fragment and scatters of Chinese ceramics and investigations, it was not uncommon to uncover bottle glass, opium tins identified the camp as being distinctively Chinese in leather strap bits, and bucket fragments immediately above or origin, while the thick green and brown glass bottles and square even mixed with dacite biface thinning flakes and other lithic nails present suggested a 19th century origin. -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

Columbia Sculpin (Cottus Hubbsi) Is a Small, Freshwater Sculpin (Cottidae)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Columbia Sculpin Cottus hubbsi in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2010 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Columbia Sculpin Cottus hubbsi in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 32 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Don McPhail for writing the provisional status report on the Columbia Sculpin, Cottus hubbsi, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the 6-month interim status report and 2-month interim status reports were overseen by Dr. Eric Taylor, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le chabot du Columbia (Cottus hubbsi) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Columbia Sculpin — illustration by Diana McPhail. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011. Catalogue No. CW69-14/268-2011E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-18590-3 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2010 Common name Columbia Sculpin Scientific name Cottus hubbsi Status Special Concern Reason for designation In Canada, this small freshwater fish is endemic to the Columbia River basin where it has a small geographic distribution. -

Syilx Okanagan Flood and Debris Flow Risk Assessment Report 4 of 4 – Quantitative Study (R4) Appendices

Syilx Okanagan Flood and Debris Flow Risk Assessment Report 4 of 4 – Quantitative Study (R4) Appendices R4 List of Appendices Appendix A: Data Summary Appendix B: Flood Hazard Assessment Appendix C: Debris Flow Hazard Assessment Syilx Okanagan Flood and Debris Flow Risk Assessment Report 4 of 4 – Quantitative Study Appendix A: Data Summary The following provides a list of data used to support the analyses presented in the Quantitative Study. Legend Hazard Data Topographic Data Exposure Data Risk Data Syilx Okanagan Flood and Debris Flow Risk Assessment, Report 4 of 4 – Quantitative Study A-1 Appendix A: Data Summary Table 1: Summary of data used for Geohazard Risk Assessment DATA DATA CONFIDENCE FILE NAME Data Purpose DATA TYPE SOURCE CATEGORY DESCRIPTION SCORE 136_GFA_FloodProne_HighMagnitude.shp Hazard used Geomorphic as the basis GFA Flood Flood Area 136_GFA_FloodProne_ModerateMagnitude.shp for the flood Shapefile Ebbwater 3 Model (GFA) Model risk 136_GFA_FloodProne_LowMagnitude.shp assessment Debris Flow Model. Hazard used Including the as the basis Debris Flow 136_Palmer_DebrisInitiationandPath debris flow for the debris Shapefile Palmer 4 Hazard Model initiation flow risk zones and assessment flow paths Flood Map Based on Soils Early Flood Geological Layers. Mapping. 136_GSM Complete.shp Shapefile Ebbwater 2 Soils Mapping Approach Flood Map Developed by Calibration AE for RDCO Provincial Flood Provincial 136_FDRP_floodplains_EPSG4617.shp FDRP Flood mapping Shapefile BC Data Catalogue 4 Flood Maps Maps calibration Flood maps produced -

The Cariboo Wagon Road

THE CARIBOO WAGON ROAD he success of the Cariboo goldfields necessitated the further Timprovement of the roads to the Cariboo. In May 1862, Colonel Richard C. Moody advised Governor James Douglas that the Yale to Cariboo route through the Fraser Canyon was the best to adapt for the general development of the country and that it was imperative its construction start at once. The governor concurred and it was decided that the road would be a full 18-feet wide in order to accommodate wagons going and coming from the goldfields and thus it came to be known as the Cariboo Wagon Road. The builders were to be paid large cash subsidies as work progressed and upon completion of their sections were to be granted permission to collect tolls from the travelers for the following 5 years. Captain John Marshall Grant of the Royal Engineers, with a force of sappers, miners, and civilian labor, was to construct the first six miles out of Yale, while Thomas Spence was to extend the road the next seven miles to Chapman’s Bar, at a cost of $47,000. From here, Joseph William Trutch, Spence’s partner, was to tackle the section to a point that would become Boston Bar, a distance of 12 miles, at a cost of $75,000. From here, Spence would continue the road to Lytton. Walter Moberly, a successful engineer, with Charles Oppenheimer, a partner in the great mercantile firm ROYAL ENGINEER'S BUCKLE & BUTTONS. COURTESY WERNER KASCHEL of Oppenheimer Brothers, and Thomas B. Lewis accepted the challenge to build the section from Lytton until the road joined a junction with the wagon road to be built by Gustavus Blin Wright and John Colin Calbreath from Lillooet to Watson’s stopping house. -

Status of the St. Mary Shorthead Sculpin (Provisionally Cottus Bairdi Punctulatus) in Alberta

Status of the St. Mary Shorthead Sculpin (provisionally Cottus bairdi punctulatus) in Alberta Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 51 Status of the St. Mary Shorthead Sculpin (provisionally Cottus bairdi punctulatus) in Alberta Prepared for: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development (SRD) Alberta Conservation Association (ACA) Prepared by: Susan M. Pollard This report has been reviewed, revised, and edited prior to publication. It is an SRD/ACA working document that will be revised and updated periodically. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 51 February 2004 Published By: i Publication No. T/050 ISBN: 0-7785-2936-3 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2937-1 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1206-4912 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1499-4682 (On-line Edition) Series Editors: Sue Peters, Nyree Sharp and Robin Gutsell Illustrations: Brian Huffman Maps: Jane Bailey For copies of this report,visit our web site at : http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ and click on “Detailed Status” OR Contact: Information Centre - Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Division Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-6424 This publication may be cited as: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. 2004. Status of the St.Mary shorthead sculpin (provisionally Cottus bairdi punctulatus) in Alberta. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Status Report No. 51, Edmonton, AB. 24 pp. ii PREFACE Every five years, the Fish and Wildlife Division of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development reviews the general status of wildlife species in Alberta.