Indo 95 0 1370968378 173

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARIP SARIPUDIN-FDK.Pdf

STRATEGI PEMENTASAN GRUP MUSIK ISLAMI “ DEBU “ SEBAGAI MEDIA DAKWAH Skripsi Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi Untuk memenuhi syarat mencapai Gelar Serjana Ilmu Sosial Islam ( S. Sos. I ) Disusun Oleh : ARIP SARIPUDIN NIM 104053002042 Jurusan Manajemen Dakwah ( MD ) Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta 1429 H / 2008 M STRATEGI PEMENTASAN GRUP MUSIK ISLAMI "DEBU" SEBAGAI MEDIA DAKWAH Skripsi Diajukan kepada Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi Untuk memenuhi syarat mencapai Gelar Sarjana Ilmu Sosial Islam (S.Sos I) Oleh Arip Saripudin Nim 103053002042 Di bawah bimbingan : Drs. Sugiharto,MA Nip: 150277690 Jurusan Manajemen Dakwah Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta 1429 M / 2008 M DAFTAR ISI ABSTRAK KATA PENGANTAR ............................................................... i DAFTAR ISI .............................................................. iv BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah …………………………………1 B. Batasan dan Rumusan Masalah ………………………. ………. 5 C. Tujuan Penelitian ………………………. ………. 5 D. Kegunaan Penelitian ………………………………... 5 E. Metodologi Penelitian ………………………. ………. 6 F. Tinjauan Pustaka ………………………………... 8 G. Sistematika Penulisan ………………………………... 9 BAB II KERANGKA TEORI A. STRATEGI 1. Pengertian Strategi ………………………………. 10 2. Dimensi strategi ………………………………. 13 3. Tahapan-tahapan Strategi ……………………………… 15 B. PEMENTASAN 1. Pengertian Pementasan ………………………………. 18 2. Tujuan dan manfaat pementasan ………………………………. 19 C. MUSIK ISLAM 1. Pengertian Musik ………………………………. 20 2. Bentuk dan Macam-macam Musik Islami ……………..................21 3. Musik Dalam Sejarah Islam ………………………..22 D. MEDIA DAKWAH 1. Pengertian Media Dakwah ………………………..25 2. Macam- macam Media Dakwah ………………………..26 3. Musik Sebagai Media Dakwah ………………………..28 BAB III GAMBARAN UMUM GRUP MUSIK ISLAMI DEBU 1. Latar Belakang Berdirinya ………………………..31 2. Visi Dan Misi Musik Debu ……………………….33 3.. Profil Personil Musik Debu ……………………….33 BAB IV STRATEGI PEMENTASAN GRUP MUSIK ISLAM DEBU A. -

Indonesian Popular Music and Identity Expressions

Indonesian popular music and identity expressions Issues of class, Islam and gender Roos Sekewaël Leiden University s1165607 Supervisor: prof. dr. David Henley 28-1-2016 CONTENTS 1 – INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________________ 1 2 – SOCIAL STRATIFICATION IN POPULAR MUSIC __________________________________________________ 5 2.1 FROM KAMPUNGAN TO GENGSI: MUSIC GENRES WITHIN CLASS BOUNDARIES _________________________________ 5 2.2 AN INTRODUCTION TO DANGDUT, POP INDONESIA AND UNDERGROUND MUSIC _______________________________ 7 2.3 CLASS STRUGGLES AND MUSICAL EXPRESSION ______________________________________________________ 8 3 – ISLAMIC IDENTITIES THROUGH POPULAR MUSIC ______________________________________________ 14 3.1 ISLAMIC REVIVALISM AND MUSLIM POP CULTURE __________________________________________________ 14 3.2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF ISLAMIC POP MUSIC ______________________________________________________ 15 3.3 NASYID'S POPULARITY IN INDONESIA ___________________________________________________________ 17 3.4 SECULAR DANGDUT MUSIC AND ISLAM __________________________________________________________ 20 4 – GENDER REPRESENTATIONS THROUGH POPULAR MUSIC _______________________________________ 23 4.1 GENDER IDEOLOGIES ______________________________________________________________________ 23 4.2 IMAGES OF FEMININITY THROUGH MUSIC VIDEOS ___________________________________________________ 25 4.3 MODERN GENDER IDEOLOGIES THROUGH SONG TEXTS _______________________________________________ 26 4.3 GENDERED -

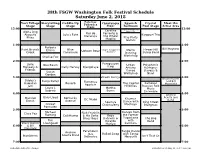

WFF Schedule

38th FSGW Washington Folk Festival Schedule Saturday June 2, 2018 Potomac Yurt Village Storytelling Cuddle-Up Palisades Chautauqua Spanish Crystal Meet the Stage Stage Stage Stage Stage Ballroom Pool Stage Artist Area 12:00 12:00 Caroline East Rising Lion Alpha Dog Dancers Acoustic Lulu's Fate Flor de Ferrante & Karpouzi Trio Blues Maracujá the Whole Play-Party Magilla Games 1:00 1:00 Barbara Bill Mayhew Paint Branch Effron Blue Uptown Boyz Singer-Songwriter Morris Flower Hill Creek Panamuse Showcase Dancing String Band Chelise Fox Workshop 2:00 2:00 Janie Noa Baum Paraguayan Urban Polyphonic Meneely & Carly Harvey Djangolaya Harp Artistry Harmony: Friends Susan Dance Slaveya & Gordon Workshop Niavi 3:00 Dawn Avery 3:00 Bruce Hutton Gabby’s Bunjo Butler Flamenco and Bill Hawaiian Reverb The Capitol Samovar Mansfield Jam Aparicio Hillbillies Russian Folk Laura J. Martha Music Bobrow Burns Ensemble 4:00 4:00 Andrew Massive Gary Lloyd Kentucky Acosta and DC Mudd Klezmer Band Donut Avenue Soumya Dance with King Street Cricket Chakraverty Machaya Bluegrass Parmalee 5:00 5:00 Dances from Cissa Paz Michael Rick Franklin Fleming Callithump & His Delta Roya the Former Blues Boys Bahrami & Yugoslavia The Bog Tim Ricardo with Band Bruce Hutton Livengood Marlow Šarenica 6:00 & Bill 6:00 Mansfield Paramount Tango Dance Andrew Jazz Ballad Swap with Tango Maelstrom Acosta Band Orchestra Mercurio Isn't That So 7:00 7:00 Schedule subject to change Schedule as of May 11, 2018 4:25 pm 38th FSGW Washington Folk Festival Schedule Sunday June 3, 2018 Potomac -

Performing Islam Through Contemporary Indonesian Popular Music, 2002-2007

PERFORMING ISLAM THROUGH INDONESIAN POPULAR MUSIC, 2002-2007 by Dorcinda Celiena Knauth BA, Lebanon Valley College, 2002 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2010 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Dorcinda Celiena Knauth It was defended on October 16, 2009 and approved by Akin Euba, PhD, Professor of Music Anne K. Rasmussen, PhD, Professor of Music, College of William and Mary Bell Yung, PhD, Professor of Music Dissertation Director: Deane L. Root, PhD, Professor of Music ii PERFORMING ISLAM THROUGH CONTEMPORARY INDONESIAN POPULAR MUSIC, 2002-2007 Dorcinda Celiena Knauth, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2010 A growing body of scholarship examines the diverse and new ways that popular music is used as a vehicle for Islamic discourse in contemporary Indonesian society. This dissertation compares three modern leaders who place their music within their own ideological context through non- musical discourse. K.H. Abdullah Gymnastiar (Aa Gym) is a preacher in Bandung whose music attempts to bring together Arabic traditions and optimistic practical advice; his piece “Jagalah Hati” shares in the theology of the Islamic philosopher Abu Hamid al-Ghazali and represents the “Managemen Qolbu” philosophies of his pesantren Daarut Tauhiid, a center for the nasyid musical style. Ahmad Dhani is a rock musician of the Jakarta band Dewa 19, who refashioned himself as a spiritual leader in order to oppose radical Islam through Islamic rock music; his songs “Satu” and “Laskar Cinta” clearly reference the philosophies of the Indonesian Sufi saint Syekh Siti Jenar. -

International Mevlana Symposiuın Papers

International Mevlana Symposiuın Papers ,. Birleşmiş Minetler 2007 Eğitim, Bilim ve Kültür MevlAnA CelAleddin ROmi Kurumu 800. ~um Yıl Oönümü United Nations Educaöonal, Scientific and aoo:ı Anniversary of Cu/tura! Organlzatlon the Birth of Rumi Symposium organization commitlee Prof. Dr. Mahmut Erol Kılıç (President) Celil Güngör Volume 3 Ekrem Işın Nuri Şimşekler Motto Project Publication Tugrul İnançer Istanbul, June 20 ı O ISBN 978-605-61104-0-5 Editors Mahmut Erol Kılıç Celil Güngör Mustafa Çiçekler Katkıda bulunanlar Bülent Katkak Muttalip Görgülü Berrin Öztürk Nazan Özer Ayla İlker Mustafa İsmet Saraç Asude Alkaylı Turgut Nadir Aksu Gülay Öztürk Kipmen YusufKat Furkan Katkak Berat Yıldız Yücel Daglı Book design Ersu Pekin Graphic application Kemal Kara Publishing Motto Project, 2007 Mtt İletişim ve Reklam Hizmetleri Şehit Muhtar Cad. Tan Apt. No: 13 1 13 Taksim 1 İstanbul Tel: (212) 250 12 02 Fax: (212) 250 12 64 www.mottoproject.com 8-12 Mayıs 2007 Bu kitap, tarihinde Kültür ve yayirı[email protected] Turizm Bakanlıgı himayesinde ve Başbakanlık Tamtma Fonu'nun katkılanyla İstanbul ve Konya'da Printing Mas Matbaacılık A.Ş. düzerılenen Uluslararası Mevhiııfı Sempozyumu bildirilerini içermektedir. Hamidiye Mahallesi, Soguksu Caddesi, No. 3 Kagıtlıane - İstanbul The autlıors are responsible for tlıe content of tlıe essays .. Tei. 0212 294 10 00 Jalaluddin Rumi in southeast Asia Nasir Tamara 1 lndonesia lN SOUTI-IEAST Asia of to day, the interest on spiritualism is on the rise especially in many major cities. This paper will talk on the lslamic mysticism, the Sufism, particularly the teaching of Jalaluddin Rumi who was bom 800 hundred years ago in Balkh, Afghanistan. -

Exploring Islamic Studies Within a Symbiotic Framework

International Seminar on Islam and Multiculturalism: Exploring Islamic Studies within a Symbiotic Framework Edited by Kazuaki Sawai, Yukari Sai, Hirofumi Okai 2014 JSPS Core-to-Core Program, B. Asia-Africa Science Platforms. Organization for Islamic Area Studies Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Southeast Asian Muslims in the Dai-Nihon Kaikyo Kyokai’s Photography Collection ONO Ryosuke* After the Second Sino ─ Japanese War broke out in 1937, the Japanese authorities (politicians, military officers, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials) and industrial conglomerate leaders took a growing interest in Asian Muslims. In this context, two Islamic political and cultural events occurred in 1938; the opening of the Tokyo Mosque (demolished in 1986) and the foundation of the Dai-Nihon Kaikyo Kyokai (Greater Japan Muslim League; hereafter, the DNKK). The DNKK promoted Islamic studies, organized exhibitions, published magazines, and pursued other cultural, economic, and intelligence activities. In short, it represented the so-called Kaikyo Seisaku (Islamic Policies) during war-time.1* The DNKK and its archives, which were long forgotten after its dissolution following Japan’s defeat in WWII, have been re-evaluated recently. The DNKK’s documents and photographs were classified as “Deposited Materials by the DNKK” one decade ago.2 At that time the Photography Collection was digitalized and produced in CD-ROM, but some of it was unclear and remained unidentified.3 The Organisation of Islamic Area Studies at Waseda University re-digitalized the same photographs and constructed a database (http://photo-kaikyokyokai. w-ias.jp/).4 It covers about 1,550 items (2,000 photos including some versos) with titles, dates, venues, key persons and so on. -

Grammatical Relations in Bahasa Indonesia

Grammatical relations in Bahasa Indonesia Vamarasi, M.K. Grammatical Relations in Bahasa Indonesia. D-93, viii + 172 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D93.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDfNG EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. To date Pacific Linguistics has published over 400 volumes in four series: • Series A: Occasional Papers; collections of shorter papers, usually on a single topic or area. -

Terms and Processes in Translation Between Indonesian and English

The University of New South Wales Department of Chinese and Indonesian Studies Terms and Processes in Translation between Indonesian and English Richard K. Johnson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2006 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the inspiration and help from my supervisor, Dr. Rochayah machali, from the very beginning of the work in 1997. In approaching translation, from the mid 1960s I have been indebted to the late Mr. H.W. Emanuels, lecturer in Indonesian, and the late Professor A.R. Davis, who taught me Chinese translation. 2 Synopsis This thesis aims to examine particular problems that the Indonesian language poses for translators, whether translating from Indonesian to English or English to Indonesian. The notation Indonesian~English translation substitutes the swung dash ~ substitutes for the hyphen -. This notation is used in this thesis to indicate translation either from Indonesian to English or from English to Indonesian. It is a convenient way to make it clear when translation is in both directions. A multifaceted approach to translation will enable translation to be viewed in much the same way as the kinds of demands it places on the translator, who needs constantly to be aware of author~reader, source~target culture, syntax, semantics, semiotics, even geography and even politics. The use of metaphor and illustrations to describe the theoretical processes of translation is justified in the same way that imagery is justified in literature. To go a step further, it is important to see through the artificial distinction often made between interpretation and translation, so that translation acquires flexibility and a deeper ethical structure. -

The Emergence of Kurdism with Special Reference to the Three Kurdish Emirates Within the Ottoman Empire, 1800-1850

The Emergence of Kurdism with Special Reference to the Three Kurdish Emirates within the Ottoman Empire, 1800-1850 Submitted by Sabah Abdullah Ghalib to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies in October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Table of Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on Transliteration and Translation viii List of Abbreviations ix Abstract x Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.1 The Scope and Purpose of the Study 1 1.2 Definitions and classifications 3 1.3 The theoretical context 9 1.4 The problem of Modernity 9 1.5 Modernist theories and Kurdism 11 1.6 Marxist theories of nationalism: Class and Kurdish nationalism 13 1.7 Historical Narratives 14 1.8 The Scope of this Study 18 1.9 The Focus of this Discussion 20 1.10 Précis of Issues discussed in each chapter 21 1.11 A note on sources 24 Chapter Two: Kurdish Tribes and their Emirates; the Socio-Political Structure 26 2.1 Introduction 26 2.2 Kurdish Dynasties and their States before the Ottomans and 26 Safavids 2.3 The beginning of the Ottoman and Safavid Empires in Kurdistan 29 2.4 The Boundaries between the Ottoman and Persian Empires 32 2.5 The Ottoman-Kurdish -

Vilayat Khan and the Emerging Sitar

Networks of Music and History: Vilayat Khan and the Emerging Sitar Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hans Utter, MA Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee Margarita Mazo, Advisor Ron Emoff Danielle Fosler-Lussier Jack Richardson Copyright by Hans Frederick Utter 2011 Abstract My dissertation explores the sitar’s rise and significance in post- independence India (1947-2009), primarily through the Imdad Khan Gharana and Vilayat Khan. Pioneering sitarists such as Ravi Shankar and Ustad Vilayat Khan were vitally important in forging India’s cultural modern identity. By studying critically the role of individual creativity in the re-imagining of tradition, my dissertation investigates how contesting cultural heritages found expression in new artistic mediums that challenged and reached new audiences. In order to create a “non- linear” history of the sitar it is conceptualized as a “quasi-object” using the semiotic- material schema found in Latour’s Actor Network Theory (Latour 2008). Musical analysis is informed by a Deleuuzian approach for the perception of multiple “truths,” exploring performance as the interpenetration of the virtual and actual in assemblages. ii Dedication Dedicated to my family and Vivek iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is ultimately a collective endeavor. The efforts of many people, generously offering their personal time, to provide information, comments, and suggestions made this work possible. In addition, several organizations including The Ohio State University with its many departments and scholarly facilities provided the necessary infrastructure and logistical support for this endeavor. -

Strengthening America's Links with Asian Muslim Communities

Making a Difference Through the Arts: Strengthening America’s Links with Asian Muslim Communities Asia Society Special Report August 2010 Lead Writer – Theodore Levin Writer and Project Coordinator – Rachel Cooper Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ....................................................................... 4 Introduction . 6 Kyrgyzstan and Post-Soviet Central Asia .................................................13 Pakistan ................................................................................29 Indonesia ...............................................................................49 Supplementary Case Studies ..............................................................72 Conclusion ..............................................................................88 Appendices ..............................................................................93 Contributors .........................................................................93 List of Sources ........................................................................95 Photo Credits .........................................................................95 2 Foreword For many Americans, the events of September 11, Art for its generous support of this initiative. The Do- 2001, and their aftermath still cast an ominous shadow ris Duke Foundation also supported an earlier report, over the regions of Asia where more than half of the “Mightier than the Sword: Arts