Volume 09 Number 04

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

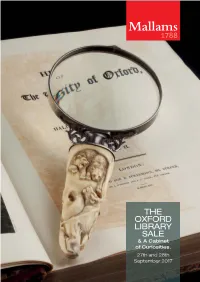

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

OXONIENSIA PRINT.Indd 253 14/11/2014 10:59 254 REVIEWS

REVIEWS Joan Dils and Margaret Yates (eds.), An Historical Atlas of Berkshire, 2nd edition (Berkshire Record Society), 2012. Pp. xii + 174. 164 maps, 31 colour and 9 b&w illustrations. Paperback. £20 (plus £4 p&p in UK). ISBN 0-9548716-9-3. Available from: Berkshire Record Society, c/o Berkshire Record Offi ce, 9 Coley Avenue, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 6AF. During the past twenty years the historical atlas has become a popular means through which to examine a county’s history. In 1998 Berkshire inspired one of the earlier examples – predating Oxfordshire by over a decade – when Joan Dils edited an attractive volume for the Berkshire Record Society. Oxoniensia’s review in 1999 (vol. 64, pp. 307–8) welcomed the Berkshire atlas and expressed the hope that it would sell out quickly so that ‘the editor’s skills can be even more generously deployed in a second edition’. Perhaps this journal should modestly refrain from claiming credit, but the wish has been fulfi lled and a second edition has now appeared. Th e new edition, again published by the Berkshire Record Society and edited by Joan Dils and Margaret Yates, improves upon its predecessor in almost every way. Advances in digital technology have enabled the new edition to use several colours on the maps, and this helps enormously to reveal patterns and distributions. As before, the volume has benefi ted greatly from the design skills of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading. Some entries are now enlivened with colour illustrations as well (for example, funerary monuments, local brickwork, a workhouse), which enhance the text, though readers could probably have been left to imagine a fl ock of sheep grazing on the Downs. -

Open Gardens

Festival of Open Gardens May - September 2014 Over £30,000 raised in 4 years Following the success of our previous Garden Festivals, please join us again to enjoy our supporters’ wonderful gardens. Delicious home-made refreshments and the hospice stall will be at selected gardens. We are delighted to have 34 unique and interesting gardens opening this year, including our hospice gardens in Adderbury. All funds donated will benefit hospice care. For more information about individual gardens and detailed travel instructions, please see www.khh.org.uk or telephone 01295 812161 We look forward to meeting you! Friday 23 May, 1pm - 6pm, Entrance £5 to both gardens, children free The Little Forge, The Town, South Newington OX15 4JG (6 miles south west of Banbury on the A361. Turn into The Town opposite The Duck on the Pond PH. Located on the left opposite Green Lane) By kind permission of Michael Pritchard Small garden with mature trees, shrubs and interesting features. Near a 12th century Grade 1 listed gem church famous for its wall paintings. Hospice stall. Wheelchair access. Teas at South Newington House (below). Sorry no dogs. South Newington House, Barford Rd, OX15 4JW (Take the Barford Rd off A361. After 100 yds take first drive on left. If using sat nav use postcode OX15 4JL) By kind permission of Claire and David Swan Tree lined drive leads to 2 acre garden full of unusual plants, shrubs and trees. Richly planted herbaceous borders designed for year-round colour. Organic garden with established beds and rotation planting scheme. Orchard of fruit trees with pond. -

Rungall, Berry Hill Road, Adderbury, Oxfordshire, OX17 3HF

Rungall, Berry Hill Road, Adderbury, Oxfordshire, OX17 3HF Rungall, Berry Hill Road, Adderbury, Oxfordshire, OX17 3HF An Impressive Detached Residence with a Separate Self- Contained Annex set in this sought after & rarely available position. The Property offers Spacious Accommodation with a Beautiful Secluded Garden which is totally enclosed. The property benefits from Gas Central Heating & Double Glazed Windows. The picturesque village of Adderbury offers many amenities including a Hotel and three Public Houses offering good food, Hair Dressers, Library, Golf Club, Recreation Ground and the Church of St Mary. The village has a good community spirit and offers many clubs ranging from babies and toddlers groups, to Brownies, Scouts, Photography, Gardening, WI, Bowls, Cricket, Tennis and Squash. Also within the village there is the Christopher Rawlins Church of England primary school. Secondary education can be found at Bloxham – the Warriner School or Bloxham School which is an independent co-educational school catering for boarders and day pupils. Alternatively, secondary education can be found at Banbury - Blessed George Napier School or North Oxfordshire Academy. Further comprehensive facilities can be found in both Banbury and Oxford. whilst access to the M40 motorway can be gained at Junctions 10 or 11. Mainline stations are also available from both Banbury and Bicester. Spacious Entrance Hall "DoubleClick Insert Picture" Cloakroom Sitting Room Dining Room Sun Room Kitchen/Breakfast Room Utility Room Master Bedroom with En-Suite Two Further Bedrooms Family Bathroom Secluded Garden Garage Annex – Sitting Room Kitchen Lobby Bedroom Shower/Wet Room Guide Description Price : £715,000 Description Local Authority Cherwell District Council Council Band F Tenure Freehold Additional Information Deddington c. -

16 Church Street, Bodicote, Banbury, Oxfordshire 16 Church Street, Bodicote, Courtyard and Good Sized Shed

16 Church Street, Bodicote, Banbury, Oxfordshire 16 Church Street, Bodicote, courtyard and good sized shed. Not suitable for pets. Floorplans Banbury, OX15 4DW House internal area 0,000 sq ft (000 sq m) Outside For identification purposes only. A well-presented 2 bedroom mid Rear courtyard with good sized shed. On street terrace property in the heart of parking Bodicote. Available for a minimum term of 12 months. Not suitable for Location Bodicote is a popular village situated to the pets south of Banbury towards Adderbury. It has a fine Parish Church dating from the 12th Century, Banbury 1.5 miles including Banbury Train a selection of pubs and a shop/post office. Station (London Marylebone from 55 minutes), further amenities are to be found in the market M40 (J11) 3 miles, Bicester 14 miles, Oxford 21 town of Banbury and Chipping Norton. Within miles, London 75 miles cycling distance of the regular rail service from Banbury to London Marylebone (approximately SITTING ROOM | KITCHEN | 2 BEDROOMS | 55 minutes). Sporting and leisure activities BATHROOM | REAR COURTYARD include Bannatyne's Heath Club, golf at EPC Rating D Adderbury and theatres in Stratford-upon-Avon, The property Chipping Norton and Oxford. Good access to Birmingham Airport to the north from the M40 16 Church Street is a well-presented mid-terrace (J11 3 miles) and London Heathrow to the south property in the heart of Bodicote. Sitting room with feature fireplace and storage cupboard. Kitchen with wood effect floor, wall and base Directions From Banbury, take the A4260 towards units, gas cooker and space for a washing Adderbury. -

Clifton Past and Present

Clifton Past and Present L.E. Gardner, 1955 Clifton, as its name would imply, stands on the side of a hill – ‘tun’ or ‘ton’ being an old Saxon word denoting an enclosure. In the days before the Norman Conquest, mills were grinding corn for daily bread and Clifton Mill was no exception. Although there is no actual mention by name in the Domesday Survey, Bishop Odo is listed as holding, among other hides and meadows and ploughs, ‘Three Mills of forty one shillings and one hundred ells, in Dadintone’. (According to the Rev. Marshall, an ‘ell’ is a measure of water.) It is quite safe to assume that Clifton Mill was one of these, for the Rev. Marshall, who studied the particulars carefully, writes, ‘The admeasurement assigned for Dadintone (in the survey) comprised, as it would seem, the entire area of the parish, including the two outlying townships’. The earliest mention of the village is in 1271 when Philip Basset, Baron of Wycomb, who died in 1271, gave to the ‘Prior and Convent of St Edbury at Bicester, lands he had of the gift of Roger de Stampford in Cliftone, Heentone and Dadyngtone in Oxfordshire’. Another mention of Clifton is in 1329. On April 12th 1329, King Edward III granted a ‘Charter in behalf of Henry, Bishop of Lincoln and his successors, that they shall have free warren in all their demesne, lands of Bannebury, Cropperze, etc. etc. and Clyfton’. In 1424 the Prior and Bursar of the Convent of Burchester (Bicester) acknowledged the receipt of thirty-seven pounds eight shillings ‘for rent in Dadington, Clyfton and Hampton’. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Response of Gosford and Water Eaton Parish Council to the Cherwell

THE CHERWELL LOCAL PLAN 2011 – 2031 (PART 1) PARTIAL REVIEW – OXFORD’S UNMET HOUSING NEED OPTIONS CONSULTATION 14 NOVEMBER – 9 JANUARY 2016 – REPRESENTATION FORM THE CHERWELL LOCAL PLAN 2011 – 2031 (PART 1) PARTIAL REVIEW – OXFORD’S UNMET HOUSING NEED OPTIONS CONSULTATION Representation Form Cherwell District Council is currently consulting on a Partial Review of the Cherwell Local Plan Part 1. The Partial Review is nOt a whOlesale review Of the LOcal Plan Part 1, which was adOpted by the COuncil On 20 July 2015. It fOcuses specifically On hOw tO accOmmOdate additiOnal hOusing and suppOrting infrastructure within Cherwell in order to help meet Oxford’s unmet hOusing needs. It is available tO view and cOmment on frOm 14 November 2016 – 9 January 2017. To view and cOmment On the dOcument and the accOmpanying Initial Sustainability Appraisal RepOrt please visit www.cherwell.gOv.uk/planningpOlicycOnsultatiOn. A summary leaflet is alsO available. The cOnsultatiOn dOcuments are alsO available tO view at public libraries acrOss the Cherwell District, at the Council’s Linkpoints at Banbury, Bicester and KidlingtOn, at Banbury and Bicester TOwn COuncils and Cherwell District COuncil’s main Office at BOdicOte House, BOdicOte, Banbury. In OxfOrd, hard cOpies are available at the OxfOrd City COuncil Offices at St Aldate’s Chambers, at Old MarstOn Library and at SummertOwn library. You may wish tO use this representatiOn fOrm tO make yOur cOmments. Please email yOur cOmments tO [email protected] or post to Planning POlicy Team, Strategic Planning and the EcOnOmy, Cherwell District COuncil, BOdicOte HOuse, BOdicOte, Banbury, OX15 4AA nO later than MOnday 9 January 2017. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society Autumn 1973 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman and Magazine Editor: F. Willy, B.A., Raymond House, Bloxham School, Banbury Hon. Secretary: Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C.G. Bloxham, B.A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G.E. Gardam Banbury Museum J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. 11 Denbigh Close Marlborough Road 1 I Westgate Broughton Road Banbury OX 16 8 DF Chichester PO 19 3ET Banbury OX1 6 OBQ (Tel. Banbury 2282) (Chichester 84048) (Tel. Banbury 2841) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members J.B. Barbour, A. Donaldson, J.F. Roberts ************** The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society’s activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E.R.C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbury’s Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury’s Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St. Mary’s Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller of Radway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History of Banbury Cross. The Society also publishes records volumes. These have included Clockmaking in Oxfordshire, 1400-1850; South Newington Churchwardens’ Accounts 1553-1684; Banbury Marriage Register, 1558-1837 (3 parts) and Baptism and Burial Register, 1558-1723 (2 parts); A Victorian M.P. -

Upper Heyford Conservation Area Appraisal (Within Rousham Conservation Area) September 2018

Upper Heyford Conservation Area Appraisal (within Rousham Conservation Area) September 2018 Place and Growth Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 3 2. Planning Policy Context 4 3. Location 6 4. Geology and Typography 8 5. Archaeology 10 6. History 11 7. Architectural History 17 8. Character and Appearance 20 9. Character Areas 23 10. Management Plan 24 11. Conservation Area Boundary 26 12. Effects of Conservation Area Designation 28 13. Design and Repair Guidance 30 14. Bibliography 32 15. Acknowledgements 33 Appendix 1. Policies 34 Appendix 2. Listof Designated Heritage Assets 35 Appendix 3. Local Heritage Assets 36 Appendix 4. Article 4 Directions 40 Appendix 5. Public consultation 42 Figure 1. Area Designations 4 Figure 2. OS location map 6 Figure 3. Aerial photography 7 Figure 4. Flood Zone 8 Figure 5. Topography 9 Figure 6. Geology 9 Figure 7. Archaeological Constraint Area 10 Figure 8. 1800 map of Upper Heyford 11 Figure 9. Enclosure map of Upper Heyford 13 Figure 10. Upper Heyford 1875 - 1887 map 15 Figure 11. Upper Heyford 1899 - 1905 map 15 Figure 12. Upper Heyford 1913 - 1923 map 16 Figure 13. Upper Heyford 1957 - 1976 map 16 Figure 14. Visual Analysis 22 Figure 15. Character Area 23 Figure 16. New conservation area boundary 21 Figure 17. Local Heritage Assets 22 Figure 18. Article 4 directions 41 2 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 1.1 What is a conservation area? an endowment for New College. A tythe barn Conservation area status is awarded to places was built for the college in the 15th century. that are deemed to be of ‘special architectural New College bought up large areas of land in or historical interest’. -

Land West of M40 Adj to A4095 Kirtlington Road Chesterton 16

Land West Of M40 Adj To A4095 16/01780/F Kirtlington Road Chesterton Case Officer: Stuart Howden Contact Tel: 01295 221815 Applicant: Clifford Smith And Robert Butcher Proposal: Change of use of land to use as a residential caravan site for 9 gypsy families, each with two caravans and an amenity building. Improvement of existing access, construction of driveway, laying of hard standing and installation of package sewage treatment plant. Expiry Date: 2nd December 2017 Extension of Time: 23rd December 2016 Ward: Fringford And Heyfords Committee Date: 15th December 2016 Ward Councillors: Cllrs Corkin, Macnamara and Wood Reason for Referral: Major Development Recommendation: Refuse 1. APPLICATION SITE AND LOCALITY 1.1 The site is located to the north of the A4095 (Kirtlington Road) and the east of the site runs adjacent to the M40, but the site sits at a higher level to this Motorway as the Motorway is within a cutting. To the north and west of the site is open countryside. The site is located approximately 1.1 KM to the north west of Chesterton as the crow flies. The 2.7 hectare site comprises of an agricultural field and a small structure to the very south of the site. Access is achieved off the Kirtlington Road at the south west corner of the site. 1.2 The site is not within close proximity to any listed buildings and is not within a Conservation Area. Public Footpath 161/11/10 is shown to run along the western boundary of the site, but is noted by the OCC Public Rights of Way Officer to likely run on the other side of this boundary. -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1979. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele chairman: Alan Donaldson, 2 Church Close, Adderbury, Banbury. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs N.M. Clifton Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury.: (Tel. Edge Hill 262) (Tel. Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hm. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, B.A., Dip. Archaeol. J.S. W. Gibson, F.S.A., Banbury Museum, 11 Westgate, Marlborough Road. Chichester PO19 3ET. (Tel: Banbury 2282) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, B.Sc., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. committee Members: Dr. E. Asser, Mr. J.B. Barbour, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs. G. W. Brinkworth, B.A., David Smith, LL.B, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover illustration is the portrait of George Fox by Chinn from The Story of Quakerism by Elizabeth B. Emmott, London (1908). CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 7 Number 9 Summer 1979 Barrie Trinder The Origins of Quakerism in Banbury 2 63 B.K. Lucas Banbury - Trees or Trade ? 270 Dorothy Grimes Dialect in the Banbury Area 2 73 r Annual Report 282 Book Reviews 283 List of Members 281 Annual Accounts 2 92 Our main articles deal with the origins of Quakerism in Banbury and with dialect in the Ranbury area.