The Knight Commander Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Commander and the Law – 2019

THE MILITARY • 2019 COMMANDER AND THE THE LAW MILITARY THE MILITARY COMMANDER AND THE LAW TE G OCA ENE DV RA A L E ’S G S D C H U J O E O H L T U N E C IT R E D FO S R TATES AI The Military Commander and the Law is a publication of The Judge Advocate General’s School. This publication is used as a deskbook for instruction at various commander courses at Air University. It also serves as a helpful reference guide for commanders in the field, providing general guidance and helping commanders to clarify issues and identify potential problem areas. Disclaimer: As with any publication of secondary authority, this deskbook should not be used as the basis for action on specific cases. Primary authority, much of which is cited in this edition, should first be carefully reviewed. Finally, this deskbook does not serve as a substitute for advice from the staff judge advocate. Editorial Note: This edition was edited and published during the Secretary of the Air Force’s Air Force Directive Publication Reduction initiative. Therefore, many of the primary authorities cited in this edition may have been rescinded, consolidated, or superseded since publication. It is imperative that all authorities cited herein be first verified for currency on https://www.e-publishing.af.mil/. Readers with questions or comments concerning this publication should contact the editors of The Military Commander and the Law at the following address: The Judge Advocate General’s School 150 Chennault Circle (Bldg 694) Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6418 Comm. -

The Order of Military Merit to Corporal R

Chapter Three The Order Comes to Life: Appointments, Refinements and Change His Excellency has asked me to write to inform you that, with the approval of The Queen, Sovereign of the Order, he has appointed you a Member. Esmond Butler, Secretary General of the Order of Military Merit to Corporal R. L. Mailloux, I 3 December 1972 nlike the Order of Canada, which underwent a significant structural change five years after being established, the changes made to the Order of Military U Merit since 1972 have been largely administrative. Following the Order of Canada structure and general ethos has served the Order of Military Merit well. Other developments, such as the change in insignia worn on undress ribbons, the adoption of a motto for the Order and the creation of the Order of Military Merit paperweight, are examined in Chapter Four. With the ink on the Letters Patent and Constitution of the Order dry, The Queen and Prime Minister having signed in the appropriate places, and the Great Seal affixed thereunto, the Order had come into being, but not to life. In the beginning, the Order consisted of the Sovereign and two members: the Governor General as Chancellor and a Commander of the Order, and the Chief of the Defence Staff as Principal Commander and a similarly newly minted Commander of the Order. The first act of Governor General Roland Michener as Chancellor of the Order was to appoint his Secretary, Esmond Butler, to serve "as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Order." 127 Butler would continue to play a significant role in the early development of the Order, along with future Chief of the Defence Staff General Jacques A. -

Fm 3-21.5 (Fm 22-5)

FM 3-21.5 (FM 22-5) HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 2003 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. *FM 3-21.5(FM 22-5) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 3-21.5 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, DC, 7 July 2003 DRILL AND CEREMONIES CONTENTS Page PREFACE........................................................................................................................ vii Part One. DRILL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. History................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Military Music....................................................................... 1-2 CHAPTER 2. DRILL INSTRUCTIONS Section I. Instructional Methods ........................................................................ 2-1 2-1. Explanation............................................................................ 2-1 2-2. Demonstration........................................................................ 2-2 2-3. Practice................................................................................... 2-6 Section II. Instructional Techniques.................................................................... 2-6 2-4. Formations ............................................................................. 2-6 2-5. Instructors.............................................................................. 2-8 2-6. Cadence Counting.................................................................. 2-8 CHAPTER 3. COMMANDS AND THE COMMAND VOICE Section I. Commands ........................................................................................ -

General Order #1

GRAND COMMANDERY KNIGHTS TEMPLAR OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Sir Knight Yves Etienne, KCT Grand Commander 1213 Avenue Z, #D-33 Brooklyn, NY 11235 Tel:: 917-207-5051 E-mail: [email protected] GENERAL ORDER NO. 1 The Commander or Recorder of each Commandery is order to distribute this Order upon receipt To: The Grand Line Officers, Past Grand Commanders, Commandery Officers and all Sir Knights of the Constituent Commanderies of the Grand Commandery of the State of New York Christian Greetings, Sir Knigts, The Theme for the Year 2020-2021 is: PROCLAMATION – INSPIRATION – CELEBRATION “PIC” PROTECT – INNOCENT – CHRISTIAN “Only the Lord gives wisdom; he gives knowledge and understanding. He stores up wisdom for those who are honest. Like a shield he protects the innocent. He makes sure that justice is done, and protects those who are loyal to him.” Proverbs 2:6-8 NCV “Lord, I need Your wisdom and understanding. I have tried for so long to operate with my own wisdom, and it just isn’t good enough. Help me to live a faithful, innocent life, free from fear and sin and worry, trusting in Your provision and protection. You are able, Lord, and I am not. Forgive me for trying to run my life and make my plans without consulting You for wisdom, understanding, guidance, and direction. Lead me, and I will follow. In Jesus’ Name, Amen.” Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Sir Knight Jeffrey N. Nelson, Most Eminent Grand Master’s General Order No. 12: It is ordered that all in-person Conclaves of Grand Constituent, or Subordinate Commanderies be prohibited until further notice. -

The Necklace As a Divine Symbol and As a Sign of Dignity in the Old Norse Conception

MARIANNE GÖRMAN The Necklace as a Divine Symbol and as a Sign of Dignity in the Old Norse Conception Introduction In the last century a wooden sculpture, 42 cm tall, was found in a small peat-bog at Rude-Eskildstrup in the parish of Munke Bjergby near Soro in Denmark. (Picture 1) The figure was found standing right up in the peat with its head ca. 30 cm below the surface. The sculpture represents a sit- ting man, dressed in a long garment with two crossed bands on its front. His forehead is low, his eyes are tight, his nose is large, and he wears a moustache and a pointed chin-beard. Part of his right arm is missing, while his left arm is undamaged. On his knee he holds an object resembling a bag. Around his neck he wears a robust trisected necklace.1 At the bottom the sculpture is finished with a peg, which indicates that it was once at- tached to a base, which is now missing (Mackeprang 1935: 248-249). It is regarded as an offering and is usually interpreted as depicting a Nordic god or perhaps a priest (Holmqvist 1980: 99-100; Ström 1967: 65). The wooden sculpture from Rude-Eskildstrup is unique of its kind. But his characteristic trisected necklace is of the same type as three famous golden collars from Västergötland and Öland. The sculpture as well as the golden necklaces belong to the Migration Period, ca. 400-550 A.D. From this period of our prehistory we have the most frequent finds of gold, and very many of the finds from this period are neck-ornaments. -

Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72

º Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72 º PREFACE Knights come in many historical forms besides the traditional Knight in shining armor such as the legend of King Arthur invokes. There are the Samurai, the Mongol, the Moors, the Normans, the Templars, the Hospitaliers, the Saracens, the Teutonic, the Lakota, the Centurions just to name a very few. Likewise today the Modern Knight comes from a great variety of Cultures, Professions and Faiths. A knight was a "gentleman soldier or member of the warrior class of the Middle Ages in Europe. In other Indo-European languages, cognates of cavalier or rider French chevalier and German Ritter) suggesting a connection to the knight's mode of transport. Since antiquity a position of honor and prestige has been held by mounted warriors such as the Greek hippeus and the Roman eques, and knighthood in the Middle Ages was inextricably linked with horsemanship. Some orders of knighthood, such as the Knights Templar, have themselves become the stuff of legend; others have disappeared into obscurity. Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in several countries, such as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, and the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state to selected persons to recognize some meritorious achievement. In the Legion of Honor, democracy became a part of the new chivalry. No longer was this limited to men of noble birth, as in the past, who received favors from their king. -

Honorary Distinctions of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Honorary distinctions of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Luxembourg orders 3 The Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau 4 The Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau 5 The Order of the Oak Crown 9 The Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg 12 Other orders, medals, crosses and insignia 15 Wearing of insignia 16 Return of insignia 16 Legislation 17 Honorary distinctions are an integral part of a nation’s cultural traditions. They reward individuals in recognition of outstanding personal or professional achievement, manifested in deeds or works, defending a cause for the good of the community or in specific fields. Principal Luxembourg orders The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg awards several orders, medals, crosses and insignia. Among this variety of honorary distinctions, the following four main orders of Luxembourg merit closer attention: - the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau; - the Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau; - the Order of the Oak Crown; - the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The Grand Duke is the grand master of these four orders, the highest title in the hierarchy of an order of chivalry, or of a civil or military decoration. The marshal of the court is the chancellor, the head of the chancellery, of the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau and of the Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau. The Minister of State, president of the government, is the chancellor of the Order of the Oak Crown and of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. -

Constitution and Code

CONSTITUTIONAL CHARTER AND CODE OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA Promulgated 27 June 1961 revised by the Extraordinary Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 CONSTITUTIONAL CHARTER AND CODE OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA Promulgated 27 June 1961 revised by the Extraordinary Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 This free translation is not be intended as a modification of the Italian text approved by the E x t r a o r d i n a ry Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 and pubblished in the Bollettino Uff i c i a l e , 12 January 1 9 9 8 . In cases of diff e r ent interpretations, the off i c i a l Italian text prevails (Art. 36, par. 3 Constitutional C h a r t e r ) . 4 CO N S T I T U T I O N A L C H A RT E R OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITA RY H O S P I TALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA 5 I N D E X Ti t l e I - TH E O R D E R A N D I T S N AT U R E . 19 A rticle 1 Origin and nature of the Order . 19 A rticle 2 P u r p o s e . 10 A rticle 3 S o v e r eignty . 11 A rticle 4 Relations with the Apostolic See . -

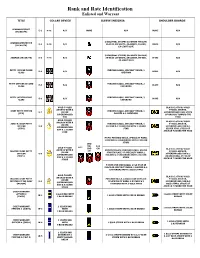

Rank and Rate Identification Enlisted and Warrant

Rank and Rate Identification Enlisted and Warrant TITLE COLLAR DEVICE SLEEVE INSIGNIA SHOULDER BOARDS SEAMAN RECRUIT E-1 NONE N/A NONE N/A NONE N/A (SR/AR/FR) 2 DIAGONAL STRIPES SA-WHITE ON BLUE, SEAMAN APPRENTICE E-2 NONE N/A SA-BLUE ON WHITE, AA-GREEN, FA-RED, NONE N/A (SA/AA/FA) CA-LIGHT BLUE 3 DIAGONAL STRIPES SN-WHITE ON BLUE, SEAMAN (SN/AN/FN) E-3 NONE N/A SN-BLUE ON WHITE, AN-GREEN, FN-RED, NONE N/A CN-LIGHT BLUE PETTY OFFICER THIRD PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 E-4 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRON PETTY OFFICER SECOND PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 2 E-5 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRONS PETTY OFFICER FIRST PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 3 E-6 N/A NONE N/A CLASS CHEVRONS GOLD FOULED BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A FOULED ANCHOR, CHIEF PETTY OFFICER PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 E-7 SILVER SUPERIMPOSED USN, STOCK (CPO) ROCKER & 3 CHEVRONS SUPERIMPOSED OF ANCHOR TOWARD THE USN HEAD GOLD FOULED BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A SENIOR CHIEF PETTY PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 FOULED ANCHOR, SILVER OFFICER E-8 ROCKER & 3 CHEVRONS WITH 1 SILVER SUPERIMPOSED USN & 1 SUPERIMPOSED (SCPO) STAR SILVER STAR, STOCK OF USN & 1 SILVER ANCHOR TOWARD THE HEAD STAR MCPO: PERCHED EAGLE, SPECIALTY MARK, 1 ROCKER & 3 CHEVERONS WITH 2 SILVER STARS CMD CM/ FOR GOLD FOULED MCPO CNO CM BLACK CLOTH W/ GOLD ANCHOR WITH A CMDCM/CNOCM: PERCHED EAGLE, SILVER MASTER CHIEF PETTY CM FOULED ANCHOR, SILVER STAR IN PLACE OF SPECIALTY MARK, 1 OFFICER E-9 SUPERIMPOSED USN & 2 SUPERIMPOSED ROCKER & 3 CHEVERONS WITH 2 SILVER (MCPO) SILVER STARS, STOCK OF USN & 2 SILVER -

The Order of Military Merit

CONTACT US Directorate of Honours a nd Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON KlA 01<2 http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhr-ddhr/ 1-877-741-8332 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2012 A-DH-300-000/JD-003 Cat. No. D2-301/2012 ISBN 978- 1- 100-54293-5 The Order of Military Merit Dedication ....... ... ....................... .......... ........ ....... ...... .... ... ............................. iii Message Her Maj esty The Queen, Sovereign of the Order of Military Merit ... .... .................................. ........... ....... ................. .. v Message His Excellency the Right Honourable David Lloyd Johnston, CC, CMM, COM, CD, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada, Chancellor of the Order of Military Merit .. .... ... ... ................... ..... ............. ............. vii Preface General Walter John Natynczyk, CMM, MSC, CD, Chief of the Defence Staff, Principal Commander of the Order of Military Merit ....................................................................... .. ix Frontispiece .......... .... ........ ................................. .................. ......... ... ................ x Author's Note ..... .......... .. ... ............. ... ....... ....... .... ....................... ......... .... .. ........ xi Acknowledgements ..... ... ................... .... .... .... ............................................................ xii Introduction ...................................................... ............................... .. ....... -

Awards Made Easy

Awards Made Easy The Layman’s Guide to Writing Civil Air Patrol Award Recommendations CAPP 39-3, June 2010 How to Use This Guide Awards Made Easy was developed to assist members at all levels submit the proper paperwork, using appropriate wording and formats to successfully recognize their fellow members for their efforts, hard work and dedication. One of the keys to being successful in obtaining recognition for CAP members or units is preparing an appropriate justification and providing additional documentation, if needed The guide is made up of various references, many of which you will not use every time and some that you will use each time you write a nomination for an award. Before you use this guide the first time, it is suggested that you go through it and become familiar with the sections that are provided to help you in preparing a nomination for an award regardless of the type. It is not mandatory that you use this guide in preparing a nomination, but it is highly suggested that you take the time to write a strong nomination, using some of the tried and true techniques included in this guide, to improve the chances that the award will be approved. 2 CAPP 39-3, June 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Award Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 4 Recommendation for Awards Checklist ..................................................................................................... 5 Award Improvement Guidelines .................................................................................................................. -

Commander John Scott Hannon (U.S. Navy, Ret.) April 11, 1971 - February 25, 2018

Commander John Scott Hannon (U.S. Navy, Ret.) April 11, 1971 - February 25, 2018 Commander John then worked as a Special Operations and Policy Staff Scott Hannon Officer at the U.S. Special Operations Command USN (Ret.), (USSOCOM) until he retired in 2012. affectionately known to his Scott’s supervisory, technical and safety qualifications family as “Scott,” include Military Freefall Specialist, Static Line Parachutist, was born April 11, NSW Sniper (Honor Graduate), Naval Gunfire Forward 1971, in Nairobi, Controller, Lead Climber, High Performance Small Boat Kenya. Born to a Coxswain, Diving Supervisor, Cast Master, Rope Master, U.S. Diplomatic Live Fire Range Supervisor, Joint Special Operations Corps family, he Planner, Amphibious Operations Planner, Advanced High grew up living in Risk Survival & Hostage Survival, Advanced Combat Tanzania, the Trauma Care Provider, Long Range MAROPS, Expeditionary Soviet Union, Warfare Staff Planning, Customized Military Mobile Force England, Belgium, Protection and others. as well as Scott was also awarded the Joint Service Commendation McLean, VA, and medal, Defense Meritorious Service medal, Navy and Helena, MT. Marine Corps Commendation medal (3), Joint Service In 1989, Scott enlisted in the U.S. Navy and qualified as a Achievement medal, and the Navy, Marine Corps Achieve- Gunner’s Mate in 1990. He graduated with BUD/S Class 173 ment medal (2) and Joint Meritorious Service Award, and in March 1991 and, upon completion of SEAL Qualification Bronze Star Medal (Gold Star in lieu of the Second Award). Training, was assigned to SEAL Team Two. After 23 years of military service, Scott retired to his family From 1995 to 1998, Scott completed multiple deployments home near Helena, Montana.