The Order of Military Merit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1930. 1895

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1930. 1895 panion of Our Distinguished Service Order, on Sir Jeremiah Colman, Baronet, Alfred Heath- whom we have conferred the Decoration of the cote Copeman, Herbert Thomas Crosby, John Military Cross, Albert Charles Gladstone, Francis Greenwood, Esquires, Lancelot Wilkin- Alexander Shaw (commonly called the Honour- son Dent, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excel- able Alexander Shaw), Esquires, Sir John lent Order of the British Empire, Edwin Gordon Nairne, Baronet, Charles Joeelyn Hanson Freshfield, Esquire, Sir James Hambro, Esquire, Sir Josiah Charles Stamp, Fortescue Flannery, Baronet, Charles John Knight Grand Cross of Our Most Excellent Ritchie, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Sir Ernest Mus- Order of the British Empire; OUR right trusty grave Harvey, Knight Commander of Our and well-beloved Charles, Lord Ritchie of Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Dundee; OUR trusty and well-beloved Sir Sir Basil Phillott Blackett, Knight Commander Alfred James Reynolds, Knight, Percy Her- of Our Most Honourable Order of the Bath, bert Pound, George William Henderson, Gwyn Knight Commander of Our Most Exalted Order Vaughan Morgan, Esquires, Frank Henry of the Star of India, Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Cook, Esquire, Companion of Our Most Knight, Edward Robert Peacock, James Lionel Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Ridpath, Esquires, Sir Homewood Crawford, Frederick Henry Keeling Durlacher, Esquire, Knight, Commander of Our Royal Victorian Colonel Sir Charles Elton Longmore, Knight Order; Sir William Jameson 'Soulsby, Knight Commander of Our Most Honourable Order of Commander of Our Royal Victorian Order, the Bath, Colonel Charles St. -

Military Commander and the Law – 2019

THE MILITARY • 2019 COMMANDER AND THE THE LAW MILITARY THE MILITARY COMMANDER AND THE LAW TE G OCA ENE DV RA A L E ’S G S D C H U J O E O H L T U N E C IT R E D FO S R TATES AI The Military Commander and the Law is a publication of The Judge Advocate General’s School. This publication is used as a deskbook for instruction at various commander courses at Air University. It also serves as a helpful reference guide for commanders in the field, providing general guidance and helping commanders to clarify issues and identify potential problem areas. Disclaimer: As with any publication of secondary authority, this deskbook should not be used as the basis for action on specific cases. Primary authority, much of which is cited in this edition, should first be carefully reviewed. Finally, this deskbook does not serve as a substitute for advice from the staff judge advocate. Editorial Note: This edition was edited and published during the Secretary of the Air Force’s Air Force Directive Publication Reduction initiative. Therefore, many of the primary authorities cited in this edition may have been rescinded, consolidated, or superseded since publication. It is imperative that all authorities cited herein be first verified for currency on https://www.e-publishing.af.mil/. Readers with questions or comments concerning this publication should contact the editors of The Military Commander and the Law at the following address: The Judge Advocate General’s School 150 Chennault Circle (Bldg 694) Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6418 Comm. -

The London Gazette of FRIDAY, the 30^ of OCTOBER, 1942 Ptiblfe^To by /Tatyority

ftumb. 35769 4761 THIRD SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of FRIDAY, the 30^ of OCTOBER, 1942 ptiblfe^to by /tatyority Registered as a newspaper TUESDAY, 3 NOVEMBER, 1942 CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD. OF KNIGHTHOOD. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. yd November, 1942. yd November, 1942. The KING has been graciously pleased to The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the British Empire approve the award of the GEORGE CROSS Medal (Military Division) to: for great gallantry and undaunted devotion to Leading Seaman George William Jackson, duty to: P/JX.i3i385. Lieutenant John Stuart Mould, G.M., Able Seaman John Henry Martin, P/JX. R.A.N.V.R. 147610. For bravery and devotion to duty. Sick Berth Attendant Ronald Stanley Thomas CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS Price, D/MX.69242. OF KNIGHTHOOD. For bravery in saving the life of three of his shipmates. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. yd November, 1942. Stoker Petty Officer Thomas Maloney, D/K. 64146. The KING has been graciously pleased to Engine Room Artificer F. Calvert, 8.476, give orders for the following appointment to R.A.N. the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire Stoker First Class Harry Grundy, D/KX. for resource and endurance in the Far East: 115288. Assistant Cook Gaunson Taylor, N.Z. 3093. To be an Additional Officer of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order: For bravery and endurance in the Far East. -

1 the Crown and Honours

The Crown and Honours: Getting it Right Christopher McCreery I N T R O D U C T I O N In the words of that early scholar of Commonwealth autonomy, Sir Arthur Berridale Keith, “The Crown is the fount of all honour.”i The role of the Crown as the fount of all official honours in Canada is a precept that is as old and constant as is the place of the Crown in our constitutional structure. Since the days of King Louis XIV residents of Canada have been honoured by the Crown for their services with a variety of orders, decorations and medals. The position of the Crown in the modern Canadian honours system is something that is firmly entrenched, despite consistent attempts to marginalize it in recent years. Indeed honours are not something separate from the Crown, they are an integral element of the Crown. A part that affords individuals with official recognition for what are deemed as good works, or in the modern context, exemplary citizenship. Just last year we witnessed the Queen’s direct involvement in the honours system when she appointed Jean Chrétien as a member of the Order of Merit. While many commentators and officials in Canada seemed confused as to just what this honour is – the highest civil honour for service – people did realize how significant it was, in large part because it came not from a committee or politician, but directly from the Sovereign. With this paper I will delve into the central role the Crown and Sovereign play in the creation of honours and I will also explore the areas where attention and reform are required in the Canadian honours system. -

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

Kaplan Auctions 115 Dunottar Street, Sydenham, 2192, Johannesburg Po Box 28913, Sandringham, 2131, R.S.A

KAPLAN AUCTIONS 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192, JOHANNESBURG PO BOX 28913, SANDRINGHAM, 2131, R.S.A. TEL: +27 11 640 6325 / 485 2195 FAX: +27 11 640 3427 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] and [email protected] Please insist on a reply. WEBSITE ADDRESS: www.aleckaplan.co.za AUCTION B89 SALE OF MEDALS, BADGES , MILITARIA & COINS 22 AUGUST 2018 TO BE HELD 06:00 PM AT OUR PREMISES – 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192 JOHANNESBURG THE LOTS WILL BE ON VIEW AT OUR PREMISES –ONLY BY APPOINTMENT. BIDDING PROCEDURE NO BIDS WILL BE ACCEPTED AFTER 12 NOON ON DAY OF AUCTION NO BIDS WILL BE PLACED WITHOUT COPY OF IDENTITY DOCUMENT 1. The Auctioneer’s decision is final. 2. Please ensure that you quote the correct lot number and recipient’s name when bidding by post. Mistakes will not be corrected after the sale. 3. This is a live auction and bids may be submitted in writing by fax, letter or e-mail, for those who cannot attend in person. 4. All items will be sold to the highest bidder. 5. Reserves have been fixed by the seller but should a reserve, in the opinion of a possible buyer be too high, I will be pleased to submit a reasonable offer to the seller, should the lot otherwise be unsold. 6. Lots have been carefully graded. Should anyone not be satisfied with the grading, such an item may be returned to us within 7 days of receipt thereof. Your payment will be refunded immediately after the goods have been received. -

The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014

The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014 CONTACT US Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhr-ddhr/ 1-877-741-8332 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014 A-DH-300-000/JD-004 Cat. No. D2-338/2014 ISBN 978-1-100-54835-7 The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, wearing her insignia of Sovereign of the Order of Canada and of the Order of Military Merit, in the Tent Room at Rideau Hall, Canada Day 2010 Photo: Canadian Heritage, 1 July 2010 Dedication To the recipients of the Meritorious Service Cross who are the epitome of Canadian military excellence and professionalism. The Meritorious Service Cross | v Table of Contents Dedication ..................................................................................................... v Introduction ................................................................................................... vii Chapter One Historical Context ........................................................................ 1 Chapter Two Statistical Analysis ..................................................................... 17 Chapter Three Insignia and Privileges ............................................................... 37 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 55 Appendix One Letters Patent Creating the Meritorious Service Cross .............. 57 Appendix Two Regulations Governing -

The Order of Military Merit to Corporal R

Chapter Three The Order Comes to Life: Appointments, Refinements and Change His Excellency has asked me to write to inform you that, with the approval of The Queen, Sovereign of the Order, he has appointed you a Member. Esmond Butler, Secretary General of the Order of Military Merit to Corporal R. L. Mailloux, I 3 December 1972 nlike the Order of Canada, which underwent a significant structural change five years after being established, the changes made to the Order of Military U Merit since 1972 have been largely administrative. Following the Order of Canada structure and general ethos has served the Order of Military Merit well. Other developments, such as the change in insignia worn on undress ribbons, the adoption of a motto for the Order and the creation of the Order of Military Merit paperweight, are examined in Chapter Four. With the ink on the Letters Patent and Constitution of the Order dry, The Queen and Prime Minister having signed in the appropriate places, and the Great Seal affixed thereunto, the Order had come into being, but not to life. In the beginning, the Order consisted of the Sovereign and two members: the Governor General as Chancellor and a Commander of the Order, and the Chief of the Defence Staff as Principal Commander and a similarly newly minted Commander of the Order. The first act of Governor General Roland Michener as Chancellor of the Order was to appoint his Secretary, Esmond Butler, to serve "as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Order." 127 Butler would continue to play a significant role in the early development of the Order, along with future Chief of the Defence Staff General Jacques A. -

For the First Time in Sunny Hills History, the ASB Has Added a Freshman, Sophomore and Junior Princess to the Homecoming Court

the accolade VOLUME LIX, ISSUE II // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // SEPT. 28, 2018 JAIME PARK | theaccolade Homecoming Royalty For the first time in Sunny Hills history, the ASB has added a freshman, sophomore and junior princess to the homecoming court. Find out about their thoughts of getting nominated on Fea- ture, page 8. Saturday’s “A Night in Athens” homecoming dance will be held for the first time in the remodeled gym. See Feature, page 9. 2 September 28, 2018 NEWS the accolade SAFE FROM STAINS Since the summer, girls restrooms n the 30s wing, 80s wing, next to Room 170 and in the Engineer- ing Pathways to Innovation and Change building have metallic ver- tical boxes from which users can select free Naturelle Maxi Pads or Naturelle Tampons. Free pads, tampons in 4 girls restrooms Fullerton Joint Union High School District installs metal box containing feminine hygiene products to comply with legislation CAMRYN PAK summer. According to the bill, the state News Editor The Fullerton Joint Union government funds these hygiene High School District sent a work- products by allocating funds to er to install pad and tampon dis- school districts throughout the *Names have been changed for pensers in the girls restrooms in state. Then, schools in need are confidentiality. the 30s wing, the 80s wing, next able to utilize these funds in order It was “that time of month” to Room 170 and in the Engineer- to provide their students with free again, and junior *Hannah Smith ing Pathways to Innovation and pads and tampons. -

Ukraine in World War II

Ukraine in World War II. — Kyiv, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, 2015. — 28 p., ill. Ukrainians in the World War II. Facts, figures, persons. A complex pattern of world confrontation in our land and Ukrainians on the all fronts of the global conflict. Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Address: 16, Lypska str., Kyiv, 01021, Ukraine. Phone: +38 (044) 253-15-63 Fax: +38 (044) 254-05-85 Е-mail: [email protected] www.memory.gov.ua Printed by ПП «Друк щоденно» 251 Zelena str. Lviv Order N30-04-2015/2в 30.04.2015 © UINR, texts and design, 2015. UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE www.memory.gov.ua UKRAINE IN WORLD WAR II Reference book The 70th anniversary of victory over Nazism in World War II Kyiv, 2015 Victims and heroes VICTIMS AND HEROES Ukrainians – the Heroes of Second World War During the Second World War, Ukraine lost more people than the combined losses Ivan Kozhedub Peter Dmytruk Nicholas Oresko of Great Britain, Canada, Poland, the USA and France. The total Ukrainian losses during the war is an estimated 8-10 million lives. The number of Ukrainian victims Soviet fighter pilot. The most Canadian military pilot. Master Sergeant U.S. Army. effective Allied ace. Had 64 air He was shot down and For a daring attack on the can be compared to the modern population of Austria. victories. Awarded the Hero joined the French enemy’s fortified position of the Soviet Union three Resistance. Saved civilians in Germany, he was awarded times. from German repression. the highest American The Ukrainians in the Transcarpathia were the first during the interwar period, who Awarded the Cross of War. -

Orders Decorations and Medals

Chap 7 ORDERS DECORATIONS AND MEDALS CHAPTER 7 ORDERS DECORATIONS AND MEDALS J237. General. Sponsor: ACOS Pers Pol (1) The Sovereign's awards to members of the Forces fall under four broad headings: (a) Awards for: (i) Gallantry and distinguished service in operational areas. (ii) Acts of gallantry not in the face of the enemy. (b) Awards for inclusion in either the New Year Honours List or the Sovereign's Birthday Honours List. (c) Medals for meritorious service or for long service and good conduct. (d) War medals for service in a specified operation or operational area. (2) In addition, Mentions-in-Despatches, Queen's Commendations for Bravery, Queen's Commendations for Bravery in the Air and Queen's Commendations for Valuable Service may be awarded. (3) Awards granted by certain civilian societies are officially recognised and may be worn in uniform. (4) Persons recommended for awards other than those mentioned in para J238(8) must be known to be alive at the time the recommendation is forwarded to PMA SPACE(AS). J238. Gallantry Awards and Operational Awards. Sponsor: ACOS Pers Pol (1) The following awards may be recommended for gallantry and distinguished service in an operational area: * Victoria Cross Companion of the Order of the Bath Commander of the Order of the British Empire * Distinguished Service Order Officer of the Order of the British Empire Member of the Order of the British Empire * Royal Red Cross (Class I) * Distinguished Service Cross * Military Cross * Distinguished Flying Cross Royal Red Cross (Class II) * Distinguished Conduct Medal * Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (Naval) * Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (Flying) * Distinguished Service Medal * Military Medal * Distinguished Flying Medal * British Empire Medal Mention-in-Despatches Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct Queen's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air. -

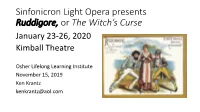

Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with Date and Length of Original London Run • Thespis 1871 (63)

Sinfonicron Light Opera presents Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse January 23-26, 2020 Kimball Theatre Osher Lifelong Learning Institute November 15, 2019 Ken Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with date and length of original London run • Thespis 1871 (63) • Trial by Jury 1875 (131) • The Sorcerer 1877 (178) • HMS Pinafore 1878 (571) • The Pirates of Penzance 1879 (363) • Patience 1881 (578) • Iolanthe 1882 (398) G&S Works, Continued • Princess Ida 1884 (246) • The Mikado 1885 (672) • Ruddigore 1887 (288) • The Yeomen of the Guard 1888 (423) • The Gondoliers 1889 (554) • Utopia, Limited 1893 (245) • The Grand Duke 1896 (123) Elements of Gilbert’s stagecraft • Topsy-Turvydom (a/k/a Gilbertian logic) • Firm directorial control • The typical issue: Who will marry the soprano? • The typical competition: tenor vs. patter baritone • The Lozenge Plot • Literal lozenge: Used in The Sorcerer and never again • Virtual Lozenge: Used almost constantly Ruddigore: A “problem” opera • The horror show plot • The original spelling of the title: “Ruddygore” • Whatever opera followed The Mikado was likely to suffer by comparison Ruddigore Time: Early 19th Century Place: Cornwall, England Act 1: The village of Rederring Act 2: The picture gallery of Ruddigore Castle, one week later Ruddigore Dramatis Personae Mortals: •Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet, disguised as Robin Oakapple (Patter Baritone) •Richard Dauntless, his foster brother, a sailor (Tenor) •Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Sir Ruthven’s younger brother