Analysis of Tools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November, 1989

Regmi Research (Private) Ltd. ISSN: 0034-348X Re i Research Series �ear 21 , No • 11 Kathmandu . November. 1989 Edited By Mahesh· C. Regmi Contents Page 1 • The Jaisi Caste . 151 2. Miscellaneous Royal Orders . 156 3. Trade Between British India. and Nepal . .. 160 ********* Regmi Resea'r�ch (Private) Ltd. Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: 4-11927 (For private study and research only; not meant for public sale, distribution and display). 151 The Jaisi Caste Previous References: 1. "The ,Jaisi Caste", Regmi Research Series, Year 2, No. 12, December 1, 1970, pp. 277-85. 2. "Upadhyaya Brahmans and Jaisis", Regmi Research Series, Year, 18, No. 5, May 19 81 , pp • 77-78. Public Notification: The following public notification was issued under the rQyal seal on Marga. Badi 3, 1856 for the following regions: (1) Dudhkosi-Arun region ( 2) Patan town (3) Rural areas of Pa.tan (4) Chepe/Narsyangdi-Gandi region (5) Pallokira.t region, east of the Arun river (6) Kali/Modi-Bheri region (7) Chepe/Marsyangdi-Kali/N.o�i region (8) Kathmandu town (9) Bhadgaun town (10) Rural areas of Bhadgaun (11) Trishuli-Gandi region (12) Tamakosi-Dudhkosi region (13) Sindhu-Tamakosi region. "You Jaisis are sons of whores. Our great-grandfather (i. e. King Prithvi Narayan Shah) had promulgated regulations prohibiting you from engaging in priestly (swa.ha., swadha) functions, and offering blessiilP'S (ashish) and greetings (Pranama), and ordering you to offer salnams instead. However, you have acted in contravention of those regulations. We accordingly punish you with fines as follows. Pay the fines to the men we have sent to collect them. -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

Border Issue with China Exposes Nepal's Unstable Foreign Policy

WI THOUT F EAR O R F A V O U R Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXIX No. 197 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 34.0 C 13.2 C Friday, September 03, 2021 | 18-05-2078 Nepalgunj Jomsom EXPLAINED What does the recent seroprevalence study mean? Two-thirds population with antibodies to Covid-19 does not mean they are immune to future infections. Misinterpretation of study could lead to surge in cases. ARJUN POUDEL checks blood samples to look for anti- KATHMANDU, SEPT 2 bodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. A seroprevalence On Monday, the Ministry of Health survey is carried out in a larger popu- and Population released a statement lation to estimate the percentage of that said a preliminary report of the the population with antibodies. nationwide seroprevalence study showed 68.6 percent of the country’s When and where was the study population has already developed carried out? antibodies to Covid-19. Officials said that the detection of Blood samples were collected from 76 antibodies in a large number of peo- districts (excluding Manang) on a ran- ple, both vaccinated and unvaccinat- dom sampling basis between July 5 ed, should be taken positively. They and August 14. The sample size was also claimed that a large-scale out- over 13,000. Those samples were tested break of Covid-19 is unlikely in the at the National Public Health immediate future. Laboratory in Teku. The study was Authorities in various districts, carried out with the technical and including in Kathmandu Valley, which financial assistance of the World is still a major coronavirus hotspot, Health Organisation. -

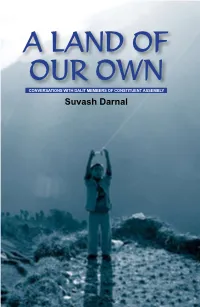

CA Books Layout.Pmd

A Land of Our Own: Conversation with Dalit member of constituent A L assembly is a collection of interviews with dalit members of the A ND OF Constituent Assembly. The formation of an inclusive CA has validated the aspirations for change embodied by 10 years long A LAND OF People’s War and People’s Movement 2006. But the Dalit Liberation O Movement continues, and the dalit representatives who are a UR part of the Assembly given the duty of writing a new constitution O OUR OWN for first time in Nepalese history have become the focus of the WN Movement. This collection of interviews, which includes the voices CONVERSATIONS WITH DALIT MEMBERS OF CONSTITUENT AssEMBLY of those who raised the flag of armed rebellion alongside those Assembly Conversations with Dalit Members of Constituent Suvash Darnal who advocated for dalit rights in the parliament and from civic and social forums, contains explosive and multi-dimensional opinions that will decimate the chains of exploitation and firmly establish dalit rights in the new constitution. It is expected that this book will assist in identifying the limits of the rights of the dalit community and of all exploited and oppressed groups, and to encourage the Constituent Assembly to write a constitution that strengthens the foundations of an inclusive democratic republic. SUVASH DARNAL is the founder of Jagaran Media Center. He has served as the Chairperson of Collective Campaign for Peace (COCAP), and is an advocate for inclusiveness in democracy. Darnal, who has published dozens of articles on dalit rights and politics, is also a co-editor of Reservation and the Politics of Special Rights. -

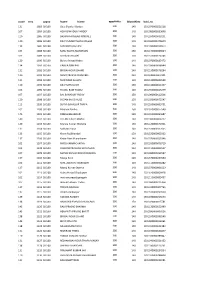

Ccode Srno Appno Fname Lname Appshkitta Allotedkitta Boid No 131

ccode srno appno fname lname appshkitta AllotedKitta boid_no 131 1083 SJCL00 Girja Shankar Baniya 300 140 1301070000221518 107 1084 SJCL00 HOM BAHADUR PANDEY 300 140 1301080000289648 120 1085 SJCL00 BASANTA PRASAD POKHREL 300 140 1301260000030231 120 1086 SJCL00 DILIP KUMAR THAPA MAGAR 300 140 1301060001275649 139 1087 SJCL00 SANTOSH GAUTAM 300 140 1301390000164973 104 1088 SJCL00 SANU MAIYA MAHARJAN 300 150 1301170000039604 102 1089 SJCL00 Rambabu Poudel 300 150 1301370000124146 120 1090 SJCL00 Bishnu Prasad Yadav 300 140 1301070000185472 134 1091 SJCL00 GANGA RAM PAL 300 140 1301280000038944 131 1092 SJCL00 BIR BAHADUR CHAND 300 140 1301130000178294 120 1093 SJCL00 SHIVA PRASAD POKHAREL 300 140 1301240000000151 131 1094 SJCL00 SURENDRA SAHANI 300 140 1301130000044538 120 1095 SJCL00 DILIP MANI DIXIT 300 150 1301130000011337 102 1096 SJCL00 THAGU RAM THARU 300 140 1301550000015279 107 1097 SJCL00 BAL BAHADUR YADAV 300 150 1301080000122596 120 1098 SJCL00 SUDAN RAJ CHALISE 300 150 1301020000072547 113 1099 SJCL00 SURYA BAHADUR THAPA 300 140 1301100000099791 102 1100 SJCL00 Madhav Pantha 300 150 1301070000077540 143 1101 SJCL00 DINESH BHANDARI 300 150 1301010000054687 140 1102 SJCL00 UTTAM SINGH MAHAT 300 140 1301380000004252 120 1103 SJCL00 Krishna Kumar Shrestha 300 150 1301120000171901 137 1104 SJCL00 Sadhana Hada 300 140 1301370000317605 133 1105 SJCL00 Khem Raj Bhandari 300 150 1301320000060332 137 1106 SJCL00 Kedar Man Munankarmi 300 140 1301370000325346 102 1107 SJCL00 NIROJ KARMACHARYA 300 140 1301100000076719 102 1108 SJCL00 UDDHAB -

ROJ BAHADUR KC DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch ABS EN

S. No. Branch Account Name Address 1 Kamalapokhari Branch MANAHARI K.C/ ROJ BAHADUR K.C DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch A.B.S. ENTERPRISES MALIGAON 3 Kamalapokhari Branch A.M.TULADHAR AND SONS P. LTD. GYANESHWAR 4 Kamalapokhari Branch AAA INTERNATIONAL SUNDHARA TAHAGALLI 5 Kamalapokhari Branch AABHASH RAI/ KRISHNA MAYA RAI RAUT TOLE 6 Kamalapokhari Branch AASH BAHADUR GURUNG BAGESHWORI 7 Kamalapokhari Branch ABC PLACEMENTS (P) LTD DHAPASI 8 Kamalapokhari Branch ABHIBRIDDHI INVESTMENT PVT LTD NAXAL 9 Kamalapokhari Branch ABIN SINGH SUWAL/AJAY SINGH SUWAL LAMPATI 10 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH BOHARA DEVKOTA CHOWK 11 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH UPRETI GOTHATAR 12 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK NEUPANE NANGIN 13 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK SHRESTHA/ BISHNU SHRESTHA BALKHU 14 Kamalapokhari Branch ACHUT RAM KC CHABAHILL 15 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION TRUST GAHANA POKHARI 16 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIV NEW ROAD 17 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIVE SOFTWARE PVT.LTD. MAHARAJGUNJ 18 Kamalapokhari Branch ADHIRAJ RAI CHISAPANI, KHOTANG 19 Kamalapokhari Branch ADITYA KUMAR KHANAL/RAMESH PANDEY CHABAHIL 20 Kamalapokhari Branch AFJAL GARMENT NAYABAZAR 21 Kamalapokhari Branch AGNI YATAYAT PVT.LTD KALANKI 22 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR NEPAL INTERNATIONAL P. LTD. HATTISAR, KAMALPOKHARI 23 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR SHANGRI-LA LTD. Thamel 24 Kamalapokhari Branch AITA SARKI TERSE, GHYALCHOKA 25 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAY KUMAR GUPTA HOSPITAL ROAD 26 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAYA MAHARJAN/SHIVA RAM MAHARJAN JHOLE TOLE 27 Kamalapokhari Branch AKAL BAHADUR THING HANDIKHOLA 28 Kamalapokhari Branch AKASH YOGI/BIKASH NATH YOGI SARASWATI MARG 29 Kamalapokhari Branch ALISHA SHRESTHA GOPIKRISHNA NAGAR, CHABAHIL 30 Kamalapokhari Branch ALL NEPAL NATIONAL FREE STUDENT'S UNION CENTRAL OFFICE 31 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED BUSINESS CENTRE RUDRESHWAR MARGA 32 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED INVESTMENT COMPANY PVT. -

Modernism and Modern Nepali Poetry – Dr

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible. -

Translation Studies Course No

Course Title: Translation Studies Course No. : Eng. Ed. 547 (Elective) Nature of course: Theoretical Level: M. Ed. Credit hours: 3 Semester: Fouth Teaching hours: 48 1. Course Description This course is aimed at exposing students to various theories and practices of translation studies. The course consists of six units. The first unit overviews basic concepts of the discipline and the second unit deals with concepts of translation equivalence. Likewise, the third unit relates translation theories with some contemporary issues and the fourth unit gives a brief account of translation tradition with reference to the Nepali–English languages pair followed by different kinds of texts for practical activities. The fifth unit sheds light on various approaches in researching translation and the last unit tries to seek the application of translation in language pedagogy. 2. General Objectives The general objectives of the course are as follows: To provide the students with an overview of translation studies. To help the students understand some major aspects of translation equivalence. To make them familiar with contemporary translation theories and issues. To acquaint the students with strategies of translating different kinds of texts by involving them in practical activities. To introduce them to some basic research approaches to translation. To familiarise them with the application of translation in language pedagogy. 3. Specific Objective and Contents Specific Objectives Contents Discuss and elaborate various Unit II: Translation Equivalence ( 7 ) dichotomies of translation equivalence 2.1 Formal and dynamic at various levels of language. 2.2 Semantic and communicative Explain the nation of approximation in 2.3 Pragmatic and textual translation 2.4 Equivalence at various levels Delineate the issue of gaps, 2.4.1 Lexical equivalence compensation, and loss and gain in 2.4.2 Collocation and idiomatic equivalence translation. -

Vasudha Pande.P65

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY AND SOCIETY New Series 37 Stratification in Kumaun circa 1815–1930 Vasudha Pande Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2013 NMML Occasional Paper © Vasudha Pande, 2013 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the opinion of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Society, in whole or part thereof. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-01-9 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Stratification in Kumaun* circa 1815–1930 Vasudha Pande** Stratification in the Pre-Modern Period In the early nineteenth century, the Kumauni caste system still retained its regional and historical specificity. Stratification in this region had emerged out of the lineage system, which had prevailed till the fifteenth century.1 The lineage system had been based upon an agrarian system dominated by Khasa community life and collective decisions had prevented the emergence of great inequalities.2 Agricultural production under the lineage system had allowed only for a distinction between peasantry and artisanal groups. The religious belief system of this period also prevented the emergence of a clear cut ritual demarcation between the artisans and the peasants, who continued to share a common village life. -

Sagarmathako(English)… Final

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible. -

TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES USED in TRANSLATING CULTURAL WORDS of PALPASA CAFÉ a Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Su

TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES USED IN TRANSLATING CULTURAL WORDS OF PALPASA CAFÉ A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Sukuna Multiple Campus In Partial Fulfillment for the Master's of Education in English By Puspa Niroula Faculty of Education Tribhuvan University Kirtipur,Nepal 2017 T.U. Reg.No:9-2- 831-29-2009 Campus Roll No: 178 Second Exam Roll No: 2140167 Date of Submission: 15 March, 2017 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is original and no part of it was earlier submitted to any university and Campus. Date: 14 March, 2017 Puspa Niroula 2 RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Ms. Puspa Niroula has worked and completed this thesis entitled ‘Translation Techniques Used In Translating Cultural Words of Palpasa Café' under my guidance and supervision. I recommend this thesis for acceptance. _____________________ Date: 15 March, 2017 Mr. Nara Prasad Bhandari (Supervisor) 3 RECOMMENDATION FOR EVALUATION This thesis entitled 'Translation Techniques Used In Translating Cultural Words of Palpasa Café' has been recommended for evaluation by the following Research Guidance Committee. Guru Prasad Adhikari signature Lecturer and Head of the Department of English …………….. Sukuna Multiple Campus (Chairperson) Nara Prasad Bhandari Lecturer Department Of English ……………… Sukuna Multiple Campus (Member) Date of approved:2017/04/ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I avail this opportunity to express my sincere and profound gratitude to Mr.Nara Prasad Bhandari, who as my honorable Guru as well as my research supervisor, helped me very much from the very beginning to the end by providing his valuable time, books and different kinds of ideas, techniques and information necessary for carrying out this research work on time. -

MA English Syllabus

Tribhuvan University Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences M.A. English Revised Courses of Study (Semester System) Prepared by English Subject Committee 2018 TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY M. A. English Program Revised Courses of Study (Semester System) 2018 1 Introduction The M.A. English courses offer students insight into literature, language, culture, and history. Besides studying required core courses that reflect the nature of the discipline, students will have the flexibility of selecting courses from different areas such as language, literature, rhetoric and humanities. While retaining the fundamental philosophy of humanities education—cultivation of humanistic values and critical thinking—this syllabus aims at developing students‘ creative, critical, and communicative skills that they need in their academic and professional life. Focus on writing, intensive study of literary genres, emphasis on interpretive and cultural theories, and the incorporation of interdisciplinary and comparative study are some of the underlying features of the courses. The syllabus requires a participatory and inquiry-based pedagogy for effective teaching and learning. The courses seek to: ∙ develop linkage between the B. A. English syllabus and the M. Phil. syllabus, ∙ apply traditional and modern literary theories while reading and teaching literary texts, ∙ train students to use English for effective communication, ∙ help students produce creative and critical writing, ∙ sharpen students creative and critical thinking, ∙ cater to students‘ need of gaining knowledge of literature and ideas, ∙ provide flexibility to the teachers in developing courses of their interests, ∙ develop courses that emphasize close reading and relationship among form, content and context, ∙ ensure application of critical theories in the interpretation of texts, and ∙ adopt interdisciplinary methods and approaches, and ∙ enable students to comprehend and respond to issues and problems.