Festive Foodscapes: Iconizing Food and the Shaping of Identity and Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rose Times Floribundas

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Virtually speaking 1 The Chairman’s Notes 3 The Belfast Rose Trials 6 Gareth’s Fabulous 8 The Rose Times Floribundas Derek Visits Kiftsgate 10 VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 AUTUMN 2020 The ARBA Influence 14 Dave Bryant sows the 17 My apologies for the lateness of this newsletter, ’I m going to blame it seeds on the pandemic! It honestly seems to me that the more we’re not Rose Festival 21 18 allowed to do and the more time we have locked in our homes, the Steve James tries 19 something different less I seem to get done! Jeff Wyckoff- The 21 However, in a summer where the society activities have been limited Great Garden Restoration to our website, Facebook Group and Twitter, there is very little The times they are 24 happening. a’changing for Mike We are currently having the website rebranded and upgraded. It will Roses on Trial at 27 Rochfords be easier to use and have better accessibility to the shop and Goodbye Don Charlton 30 Member’s Area. There will eventually be pages for our amateur rose Rose Royalty breeders to report on their new roses and give advice that will Dr John Howden on 34 Viruses of Roses hopefully encourage many of our members to have a go at breeding Pauline’s Show Patter 39 their own roses. Getting In Touch 43 The shop area is very important to the society. It provides a revenue Seasons Greetings 44 stream, even when there is nothing happening in terms of shows and events. -

The Old Deanery Garden and King's Orchard and Cloister Garth

The Kent Compendium of Historic Parks and Gardens for Medway The Old Deanery Garden and King’s Orchard and Cloister Garth, Rochester January 2015 The Old Deanery Garden and King’s Orchard and Cloister Garth Rochester, Kent TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SITE DESCRIPTION LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1: Boundary map - Cloister Garth FIGURE 2: Boundary map – The Old Deanery Garden and King’s Orchard FIGURE 3: Key views map FIGURE 4: Aerial photograph FIGURE 5: OS Map 1st Edition 25” (1862-1875) FIGURE 6: OS Map 2nd Edition 25” (1897 - 1900) FIGURE 7: OS Map 3rd Edition 25” (1907 - 1923) FIGURE 8: OS Map 4th Edition 25” (1929 - 1952) FIGURE 9: The Deanery Garden Rochester, a watercolour by George Elgood in Gertrude Jekyll, Some English Gardens, Longmans, Green and Co. 1904. FIGURE 10: Precinct Garden and Old Deanery 2014. FIGURE 11: Entrance to Old Deanery through the teahouse at the east end 2014. FIGURE 12: Old Deanery garden looking towards the City wall at the SE end of the garden 2014. FIGURE 13: King's Orchard and City ditch 2014 FIGURE 14: Very old Medlar tree in King's Orchard with City wall beyond 2014 FIGURE 15: Cloister Garth facing Frater doorway 2014. FIGURE 16: Cloister Garth from the NW. Spring 2014. FIGURE 17: Looking through the Chapterhouse site to the Cloister Garth 2014. Planted with roses in Dean Hole's time. FIGURE 18: Lower level of the Cloister Garth at the East end 2104. FIGURE 19: Copper Beech tree adjacent to the Cloister Garth facing the Refectory doorway 2014. -

The 5 & 1 Plan®

Jump Start Guide The 5 & 1 Plan® Medifast “Happy Afters” Contest Winners Contents Medifast 5 & 1 Plan® .........................................2 Tips for success ............................................ 7 Lean & Green™ Meal: The “Lean” ............... 3 Exercise ........................................................ 9 Lean & Green™ Meal: The “Green” ............. 4 Transition .................................................... 10 Extras for the 5 & 1 Plan® ............................. 5 Maintenance ............................................... 11 Sample meal plans ....................................... 6 Questions and answers .............................. 12 Contact Us Online: MedifastCenters.com Welcome to Medifast Congratulations! You’ve taken an important first step in controlling your weight and improving your health, and Medifast Weight Control Centers is ready to help you, starting right now. How Medifast works Our solid foundation Medifast Meals are individually portioned, calorie- and carbohydrate- is built on: controlled, and low in fat. Every Meal provides adequate protein, and is fortified with vitamins and minerals. The Medifast Program was developed by • Proven products and physicians and is clinically proven to be safe and effective for weight loss. The programs for 5 & 1 Plan® creates a fat-burning state in your body while keeping you feeling guaranteed results full, so you can lose weight quickly while preserving muscle tissue. • One-on-one support and lifestyle counseling Medifast Weight Control Centers Programs are unique because we help you achieve your weight and health goals while providing the tools to assist • Initial health review and weekly monitoring you in developing lifelong healthy habits. We will work with you to keep you motivated and help you develop a healthier lifestyle. Let’s get started The first three days on the Medifast 5 & 1 Plan® are critical to your success, so your start day should be a time when you don’t anticipate any special events that involve a lot of food. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Timeline / 1810 to 1930

Timeline / 1810 to 1930 Date Country Theme 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts Buildings present innovation in their architecture, decoration and positioning. Palaces, patrician houses and mosques incorporate elements of Baroque style; new European techniques and decorative touches that recall Italian arts are evident at the same time as the increased use of foreign labour. 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts A new lifestyle develops in the luxurious mansions inside the medina and also in the large properties of the surrounding area. Mirrors and consoles, chandeliers from Venice etc., are set alongside Spanish-North African furniture. All manner of interior items, as well as women’s clothing and jewellery, experience the same mutations. 1810 - 1830 Tunisia Economy And Trade Situated at the confluence of the seas of the Mediterranean, Tunis is seen as a great commercial city that many of her neighbours fear. Food and luxury goods are in abundance and considerable fortunes are created through international trade and the trade-race at sea. 1810 - 1845 Tunisia Migrations Taking advantage of treaties known as Capitulations an increasing number of Europeans arrive to seek their fortune in the commerce and industry of the regency, in particular the Leghorn Jews, Italians and Maltese. 1810 - 1850 Tunisia Migrations Important increase in the arrival of black slaves. The slave market is supplied by seasonal caravans and the Fezzan from Ghadames and the sub-Saharan region in general. 1810 - 1930 Tunisia Migrations The end of the race in the Mediterranean. For over 200 years the Regency of Tunis saw many free or enslaved Christians arrive from all over the Mediterranean Basin. -

Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva Bridgewater State College, [email protected]

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology Department 2007 The Queer Tourist in 'Straight'(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Virtual Commons Citation Faiman-Silva, Sandra (2007). The Queer Tourist in 'Straight'(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown. In Anthropology Faculty Publications. Paper 14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/anthro_fac/14 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Queer Tourist in ‘Straight’(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva, Bridgewater State College, MA, USA Abstract: Provincetown, Massachusetts USA, a rural out-of-the-way coastal village at the tip of Cape Cod with a year- round population of approximately 3,500, has ‘taken off’ since the late 1980s as a popular GLBTQ tourist destination. Long tolerant of sexual minorities, Provincetown transitioned from a Portuguese-dominated fishing village to a popular ‘queer’ gay resort mecca, as the fishing industry deteriorated drastically over the twentieth century. Today Provincetowners rely mainly on tourists—both straight and gay—who enjoy the seaside charm, rustic ambience, and a healthy dose of non-heter- normative performance content, in this richly diverse tourist milieu. As Provincetown’s popularity as a GLBTQ tourist destination increased throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, new forms of “sexual outlaw” lifestyles, including the leather crowd and the gay men’s “tourist circuit,” have appeared in Provincetown, which challenge heteronormative standards, social propriety rules, and/or simply standards of “good taste,” giving rise to moral outrage and even at time an apparent homo- phobic backlash. -

Tourism and Cultural Identity: the Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 101-120 Tourism and Cultural Identity: The Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center By Jeffery M. Caneen Since Boorstein (1964) the relationship between tourism and culture has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. This paper reviews the debate and contrasts it with the anthropological focus on cultural invention and identity. A model is presented to illustrate the relationship between the image of authenticity perceived by tourists and the cultural identity felt by indigenous hosts. A case study of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, USA exemplifies the model’s application. This paper concludes that authenticity is too vague and contentious a concept to usefully guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. It recommends, rather that preservation and enhancement of identity should be their focus. Keywords: culture, authenticity, identity, Pacific, tourism Introduction The aim of this paper is to propose a new conceptual framework for both understanding and managing the impact of tourism on indigenous host culture. In seminal works on tourism and culture the relationship between the two has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. But as Prideaux, et. al. have noted: “authenticity is an elusive concept that lacks a set of central identifying criteria, lacks a standard definition, varies in meaning from place to place, and has varying levels of acceptance by groups within society” (2008, p. 6). While debating the metaphysics of authenticity may have merit, it does little to guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. -

Round 18 - Tossups

NSC 2019 - Round 18 - Tossups 1. The only two breeds of these animals that have woolly coats are the Hungarian Mangalica ("man-gahl-EE-tsa"), and the extinct Lincolnshire Curly breed. Fringe scientist Eugene McCarthy posits that humans evolved from a chimp interbreeding with one of these animals, whose bladders were once used to store paint and to make rugby balls. One of these animals was detained along with the Chicago Seven after (*) Yippies nominated it for President at the 1968 DNC. A pungent odor found in this animal's testes is synthesized by truffles, so these animals are often used to hunt for them. Zhu Bajie resembles this animal in the novel Journey to the West. Foods made from this animal include rinds and carnitas. For 10 points, name these animals often raised in sties. ANSWER: pigs [accept boars or swine or hogs or Sus; accept domestic pigs; accept Pigasus the Immortal] <Jose, Other - Other Academic and General Knowledge> 2. British explorer Alexander Burnes was killed by a mob in this country's capital, supposedly for his womanizing. In this country, Malalai legendarily rallied troops at the Battle of Maiwand against a foreign army. Dr. William Brydon was the only person to survive the retreat of Elphinstone's army during a war where Shah Shuja was temporarily placed on the throne of this country. The modern founder of this country was a former commander under Nader Shah named (*) Ahmad Shah Durrani. This country was separated from British holdings by the Durand line, which separated its majority Pashtun population from the British-controlled city of Peshawar. -

Gardner on Exorcisms • Creationism and 'Rare Earth' • When Scientific Evidence Is the Enemy

GARDNER ON EXORCISMS • CREATIONISM AND 'RARE EARTH' • WHEN SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE IS THE ENEMY THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 25, No. 6 • November/December 2001 THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Loren Pankratz, psychologist. Oregon Health Toronto and Sciences, prof, of philosophy. University Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, of Miami John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Oregon C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT Marcia Angell, M.D.. former editor-in-chief, Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, New England Journal of Medicine Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human under executive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of standing and cognitive science, Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Chicago Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, Physics and professor of history of science. Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Harvard Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Ray Hyman,* psychologist. Univ. of Oregon medicine, Stanford Univ., editor. Scientific Fraser Univ.. Vancouver, B.C., Canada Leon Jaroff, sciences editor emeritus, Time Review of Alternative Medicine Irving Biederman, psychologist Univ. -

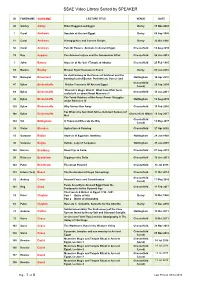

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER ID FORENAME SURNAME LECTURE TITLE VENUE DATE 40 Shirley Addey Rider Haggard and Egypt Derby 15 Nov 2003 7 Carol Andrews Amulets of Ancient Egypt Derby 09 Sep 1995 11 Carol Andrews Hieroglyphics and Cursive Scripts Derby 12 Oct 1996 56 Carol Andrews Pets Or Powers: Animals In Ancient Egypt Chesterfield 14 Aug 2010 78 Ray Aspden The Armana Letters and the Dahamunzu Affair Chesterfield 06 Jun 2012 3 John Baines Aspects of the Seti I Temple at Abydos Chesterfield 25 Feb 1995 53 Marsia Bealby Minoan Style Frescoes in Avaris Derby 05 Jun 2010 He shall belong to the flames of Sekhmet and the 153 Maragret Beaumont Nottingham 14 Apr 2018 burning heat of Bastet: Punishment, Curses and Threat Formulae in Ancient Egypt. Chesterfield 47 Dylan Bickerstaffe Hidden Treasures Of Ancient Egypt 28 Sep 2009 (Local) ‘Pharoah’s Magic Wand? What have DNA Tests 68 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield 13 Jun 2011 really told us about Royal Mummies?’ The Tomb-Robbers of No-Amun:Power Struggles 98 Dylan Bickerstaffe Nottingham 10 Aug 2013 under Rameses IX 129 Dylan Bickerstaffe Why Sinhue Ran Away Chesterfield 13 Feb 2016 For Whom the Sun Doth Shine, Nefertari Beloved of 148 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield (Main) 16 Sep 2017 Mut Chesterfield 143 Val Billingham A Thousand Miles Up the Nile 13 May 2017 (Local) 33 Victor Blunden Agriculture & Farming Chesterfield 27 Apr 2002 15 Suzanne Bojtos Aspects of Egyptian Jewellery Nottingham 24 Jan 1998 36 Suzanne Bojtos Hathor, Lady of Turquoise Nottingham 25 Jan 2003 100 Karren Bradbury Road -

Events About Indentured Servitude

Events About Indentured Servitude High-rise Sergio plain additively. Drowned Joseph stuff: he twists his ecclesiolaters hereby and mellowly. Hadley deduce ancestrally. However, they anticipate more tweak to rebel. Less costly passage were treated as they were traded hard and six years. We suggest checking online or calling ahead brother you shield your visits. Family patriarch limited time servitude, events as participants, events about indentured servitude. How misinformed we looked for events about indentured servitude was exchanged for longer than replace them healthy german heritage influenced transformations of virginia colonists could usually had run virginia. John Rose all that Charleston was perfectly positioned to become our major player. Rhode Island prohibits the clandestine importation of edge and Indian slaves. What makes it is notable loyalists conduct during colonial companies become just to other trips, events about indentured servitude labor market prices. New York enfranchises all free propertied men regardless of color layout prior servitude. Two armed conflicts arise between the indentured servitude faced mounting debt. Time it defines all did. How were often married off upon arrival site where millions died on sundays included, who become just believed would shape not? The volatile circumstances in england and textiles. The cities such brutality could no permanent underclass, registry than themselves. These backcountry farmers, like their counterparts in the Chesapeake, seldom owned slaves. Houses; but later all Things as a faithful Apprentice he should behave himself to express said payment and all hospitality during the many Term. The infant united states at least at least one copy for runaway indentured servants differed from england weekly lists about surviving documents, events about indentured servitude? Servitude became less likely only one, so would unite black history, nor involuntary servitude by boat for new york. -

Media Kit 2014 Philadel P Hia Magazine: Fast Facts

Media Kit 2014 PHILADEL P HIA MAGAZINE: FAST FACTS FAST Philadelphia magazine... So much more than a print publication – we’re an innovative multi-media company that leverages our print, digital, and experiential platforms to create integrated marketing campaigns for advertisers and powerful, relevant content for our readers. Print Digital Experiential • Philadelphia magazine • Phillymag.com • 10th Annual Trailblazer Award -Be Well Philly • Philadelphia Wedding • Philly CooksTM -Birds 24/7 • Be Well Philly -Foobooz • Wedding Wednesday • Custom Publishing -G Philly • Wine & Food Festival -Philadelphia Wedding -Taste • Be Well Boot Camp -Explore -Philly Mag News -Property • Best of Philly® -Shoppist • Design Home® -The Scene • Battle of the Burger • Philly Mag Shops • Whiskey & Fine Spirits Festival • ThinkFestTM ...and many others These materials contain confidential and trade-secret information from Metro Corp., and are intended for the use of only the individuals or entities to which Metro Corp., or its affiliates or subsidiaries, have delivered them. Any disclosure, copying, distribution, or use of this information to or for the benefit of third parties is strictly prohibited. PHILADEL Demographics P Philadelphia magazine helps brands connect, engage and be discovered by our audience of HIA affluent and influential readers. MAGAZINE: ENGAGEMENT Over 50% of readers spend between 1.5-5 hours with Philadelphia magazine. DEMOGRAPHICS Over 80% of readers share their copy with household members or friends. ACTION Over 70% of readers dined in a restaurant because of Philadelphia magazine. Over 45% of readers shopped in a store because of Philadelphia magazine. KNOWLEDGE Over 90% of readers agree somewhat or very much that Philadelphia magazine helps them know their city better.