Second Homes Russian/Ukrainian Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dacha Sweet Dacha Place Attachment in the Urban Allotment Gardens of Kaliningrad, Russia Pavel Grabalov

Dacha Sweet Dacha Place Attachment in the Urban Allotment Gardens of Kaliningrad, Russia Pavel Grabalov Urban Studies Two-year Master Programme Thesis, 30 credits Spring/2017 Supervisor: Tomas Wikström 2 Lopakhin: Up until now, in the countryside, we only had landlords and peasants, but now we have summer people. All the towns, even the smallest ones are surrounded by summer cottages [dachas] now. And it’s a sure thing that in twenty years’ time summer people will have multiplied to an incredible extent. Today a person is sitting on his balcony drinking tea, but he could start cultivating his land, and then your cherry orchard will become a happy, rich, and gorgeous place… Anton Chekhov, “The Cherry Orchard” (1903), translated by Marina Brodskaya Cover photo: The urban allotment gardens on Katina street in Kaliningrad. December 2017. Source: Artem Kilkin. 3 Grabalov, Pavel. “Dacha Sweet Dacha: Place Attachment in the Urban Allotment Gardens of Kaliningrad, Russia.” Master of Science thesis, Malmö University, 2017. Summary Official planning documents and strategies often look at cities from above neglecting people’s experiences and practices. Meanwhile cities as meaningful places are constructed though citizens’ practices, memories and ties with their surroundings. The purpose of this phenomenological study is to discover people’s bonds with their urban allotment gardens – dachas – in the Russian city of Kaliningrad and to explore the significance of these bonds for city development. The phenomenon of the dacha has a long history in Russia. Similar to urban allotment gardens in other countries, dachas are an essential part of the city landscape in many post-socialist countries but differ by their large scale. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992, No.26

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

The Phenomenon of Transitivity in the Ukrainian Language

THE PHENOMENON OF TRANSITIVITY IN THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE 2 CONTENT INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………… 3 Section 1. GENERAL CONCEPT OF TRANSITIVITY……………………. 8 Liudmyla Shytyk. CONCEPTS OF TRANSITIVITY IN LINGUISTICS……... 8 1.1. The meaning of the term «transition» and «transitivity»…………….. 8 1.2. Transitivity typology…………………………………………………... 11 1.3. The phenomenon of syncretism in the lingual plane…………………. 23 Section 2. TRANSITIVITY PHENOMENA IN THE UKRAINIAN LEXICOLOGY AND GRAMMAR…………………………………………... 39 Alla Taran. SEMANTIC TRANSITIVITY IN VOCABULARY……………… 39 Iryna Melnyk. TRANSPOSITIONAL PHENOMENA IN THE PARTS OF SPEECH SYSTEM……………………………………………………………… 70 Mykhailo Vintoniv. SYNCRETISM IN THE SYSTEM OF ACTUAL SENTENCE DIVISION………………………………………………………… 89 Section 3. TRANSITIVITY IN AREAL LINGUISTIC……………………... 114 Hanna Martynova. AREAL CHARAKTERISTIC OF THE MID-UPPER- DNIEPER DIALECT IN THE ASPECT OF TRANSITIVITY……………….... 114 3.1. Transitivity as areal issue……………………………………………… 114 3.2. The issue of boundary of the Mid-Upper-Dnieper patois…………….. 119 3.3. Transitive patois of Podillya-Mid-Upper-Dnieper boundary…………. 130 Tetiana Tyshchenko. TRANSITIVE PATOIS OF MID-UPPER-DNIEPER- PODILLYA BORDER………………………………………………………….. 147 Tetiana Shcherbyna. MID-UPPER-DNIEPER AND STEPPE BORDER DIALECTS……………………………………………………………………… 167 Section 4. THE PHENOMENA OF SYNCRETISM IN HISTORICAL PROJECTION…………………………………………………………………. 198 Vasyl Denysiuk. DUALIS: SYNCRETIC DISAPPEARANCE OR OFFICIAL NON-RECOGNITION………………………………………………………….. 198 Oksana Zelinska. LINGUAL MEANS OF THE REALIZATION OF GENRE- STYLISTIC SYNCRETISM OF A UKRAINIAN BAROQUE SERMON……. 218 3 INTRODUCTION In modern linguistics, the study of complex systemic relations and language dynamism is unlikely to be complete without considering the transitivity. Traditionally, transitivity phenomena are treated as a combination of different types of entities, formed as a result of the transformation processes or the reflection of the intermediate, syncretic facts that characterize the language system in the synchronous aspect. -

Halyna Pshenichkina Ethnographic Regions in the Territory of Contemporary Cherkasy District by Features of Ritual Folk Songs 149

148 RES HUMANITARIAE XXV, 2019, 148–160 ISSN 1822-7708 Halyna Pšeničkina – Ukrainos nacionalinės P. I. Čaikovskio muzikos akademijos Ukrainos muzikos istorijos ir muzikinės folkloristikos katedros aspirantė, Dnipropetrovsko m. M. Glinkos muzikos akademijos Muzikos istorijos ir teo- rijos katedros lektorė, Čerkasų S. S. Hulak-Artemovskio aukštesniosios muzikos mokyklos lektorė Moksliniai interesai: etnomuzikologija, folkloristika, etnologija Adresas: Popovo g. 3/1, Čerkasai, 18030, Ukraina Tel.: + 38 097 719 06 39 El. paštas: [email protected] Halyna Pshenichkina: PhD student at Department of History of Ukrainian Music and Musical Folkloristics, P. I. Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine in Kyiv; Lecturer at Department of History and Theory of Music at Dnipropetrovsk M. Glinka Academy of Music, Dnipro city; Lecturer at Cherkasy S. S. Hulack-Artemovskyy Music College Research interests: ethnomusicology, folkloristics, ethnology Address: Popova lane 3/1, Cherkasy, 18030, Ukraine Phone: + 38 097 719 06 39 E-mail: [email protected] Halyna Pshenichkina P. I. Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine; Dnipropetrovsk M. Glinka Academy of Music; Cherkasy S. S. Hulack-Artemovskyy Music College ETHNOGRAPHIC REGIONS IN THE TERRITORY OF CONTEMPORARY CHERKASY DISTRICT BY FEATURES OF RITUAL FOLK SONGS Anotacija Centrinėje Dniepro upės vietovių teritorijoje yra žinomi trys skirtingi Ukrainos etnografiniai regi- onai, pasižymintys savitomis liaudies dainavimo tradicijomis. Visi jie siekia Čerkasų rajono ribas pagal šių laikų administracinio -

Urgently for Publication (Procurement Procedures) Annoucements Of

Bulletin No�1 (180) January 7, 2014 Urgently for publication Annoucements of conducting (procurement procedures) procurement procedures 000162 000001 Public Joint–Stock Company “Cherkasyoblenergo” State Guard Department of Ukraine 285 Gogolia St., 18002 Cherkasy 8 Bohomoltsia St., 01024 Kyiv–24 Horianin Artem Oleksandrovych Radko Oleksandr Andriiovych tel.: 0472–39–55–61; tel.: (044) 427–09–31 tel./fax: 0472–39–55–61; Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: e–mail: [email protected] www.tender.me.gov.ua Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Procurement subject: code DK 016–2010 (19.20.2) liquid fuel and gas; www.tender.me.gov.ua lubricating oils, 4 lots: lot 1 – petrol А–95 (petrol tanker norms) – Procurement subject: code 27.12.4 – parts of electrical distributing 100 000 l, diesel fuel (petrol tanker norms) – 60 000 l; lot 2 – petrol А–95 and control equipment (equipment KRU – 10 kV), 7 denominations (filling coupons in Ukraine) – 50 000,00, diesel fuel (filling coupons in Supply/execution: 82 Vatutina St., Cherkasy, the customer’s warehouse; Ukraine) – 30 000,00 l; lot 3 – petrol А–95 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – till 15.04.2014 60 000,00; lot 4 – petrol А–92 (filling coupons in Kyiv) – 30 000,00 Procurement procedure: open tender Supply/execution: 52 Shcherbakova St., Kyiv; till December 15, 2014 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: 285 Hoholia St., 18002 Cherkasy, Procurement procedure: open tender the competitive bidding committee Obtaining of -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

List of Persons and Entities Under EU Restrictive Measures Over the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine

dhdsh PRESS Council of the European Union EN 1st December 2014 List of persons and entities under EU restrictive measures over the territorial integrity of Ukraine List of persons N. Name Identifying Reasons Date of information listing 1. Sergey Valeryevich d.o.b. 26.11.1972 Aksyonov was elected “Prime Minister of Crimea” in the Crimean Verkhovna Rada on 27 17.3.2014 Aksyonov February 2014 in the presence of pro-Russian gunmen. His “election” was decreed unconstitutional by Oleksandr Turchynov on 1 March. He actively lobbied for the “referendum” of 16 March 2014. 2. Vladimir Andreevich d.o.b. 19.03.1967 As speaker of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Konstantinov 17.3.2014 Konstantinov played a relevant role in the decisions taken by the Verkhovna Rada concerning the “referendum” against territorial integrity of Ukraine and called on voters to cast votes in favour of Crimean Independence. 3. Rustam Ilmirovich d.o.b. 15.08.1976 As Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Crimea, Temirgaliev played a relevant role 17.3.2014 Temirgaliev in the decisions taken by the Verkhovna Rada concerning the “referendum” against territorial integrity of Ukraine. He lobbied actively for integration of Crimea into the Russian Federation. 4. Deniz Valentinovich d.o.b. 15.07.1974 Berezovskiy was appointed commander of the Ukrainian Navy on 1 March 2014 and swore an 17.3.2014 Berezovskiy oath to the Crimean armed force, thereby breaking his oath. The Prosecutor-General’s Office of Ukraine launched an investigation against him for high treason. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

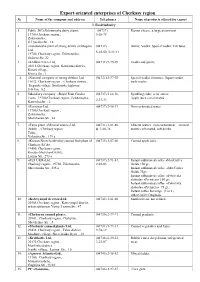

Export-Oriented Enterprises of Cherkasy Region № Name of the Company and Address Telephones Name of Products Offered for Export I

Export-oriented enterprises of Cherkasy region № Name of the company and address Telephones Name of products offered for export I. Food industry 1. Public JSC«Zolotonosha dairy plant», (04737) Rennet cheese, a large assortment 19700,Cherkasy region., 5-26-78 Zolotonosha , G.Lysenko Str., 18 2. «Zolotonosha plant of strong drinks «Zlatogor» (04737) Balms; Vodka; Special vodka; Tinctures. Ltd, 5-23-50, 5-39-41 19700, Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Sichova Str, 22 3. «Khlibna Niva» Ltd, (04732) 9-79-69 Vodka and spirits. 20813,Cherkasy region, Kamianka district, Kosari village, Kirova Str., 1 4. «National company of strong drinks» Ltd, (0472) 63-37-70 Special vodka, tinctures, liquers under 19632, Cherkasy region., Cherkasy district , trade marks. Stepanki village, Smilianske highway, 8-th km, б.2 5. Subsidiary company «Royal Fruit Garden (04737) 5-64-26, Sparkling cider, semi-sweet; East», 19700,Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Apple juice concentrated 2-27-73 Kanivska Str. , 2 6. «Econiya» Ltd, (04737) 2-16-37 Non-carbonated water. 19700,Cherkasy region , Zolotonosha , Shevchenko Str., 24 7. «Talne plant «Mineral waters»Ltd., (04731) 3-01-88, Mineral waters non-carbonated, mineral 20400, ., Cherkasy region ф. 3-08-36 waters carbonated, soft drinks Talne, Voksalna Str., 139 а 8. «Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy canned fruit plant of (04735) 2-07-60 Canned apple juice Cherkasy RCA», 19400, Cherkasy region., Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy, Lenina Str., 273 а 9. «FES UKR»Ltd, (04737) 2-91-84, Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Cherkasy region., 19700, Zolotonosha, 2-92-03 Gold» 150 gr; Shevchenka Str., 235 а Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Gold» 75gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 150 gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 75 gr.; Instant coffee beverage (3 in 1) «MacCoffee Original». -

Dacha Dwellers and Gardeners: Garden Plots and Second Houses in Europe and Russia

Population and Economics 3(1): 107–124 DOI 10.3897/popecon.3.e34783 RESEARCH ARTICLE Dacha dwellers and gardeners: garden plots and second homes in Europe and Russia Alexander V. Rusanov1 1 Faculty of Geography, The Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia Received 1 February 2019 ♦ Accepted 25 March 2019 ♦ Published 12 April 2019 Citation: Rusanov AV (2019) Dacha dwellers and gardeners: garden plots and second homes in Europe and Russia. Population and Economics 3(1): 107–124. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.3.e34783 Abstract One of the ways to solve the problems associated with rapid growth of urban population and the development of industry in Western Europe in the 19th century was the creation of collective gar- dens and vegetable plots, which could be used to grow food for personal consumption. The peak of their popularity was during the First and Second World Wars. In the second half of the 20th century, as food shortages decrease, the number of garden plots in Western Europe sharply decreased. The revival of interest in gardening at the end of the 20 century is connected with the development of na- ture protection movement and ecological culture. In Eastern Europe, most of the collective gardens and vegetable plots appeared after the Second World War in a planned economy, they were most popular during the periods of economic recession. In some countries – Russia, Poland – gardeners have now become one of the largest land users. The article deals with the history and main factors that influenced the development of collective gardening and vegetable gardening in Europe and ana- lyzes the laws presently regulating the activity of gardeners. -

Dacha Beer Garden Shaw Washington Dc

DACHA BEER GARDEN SHAW WASHINGTON DC BEER GARDEN ESSENTIALS FRIED PICKLES tzatziki crème 8 v CURRYWURST berliner ketchup, crispy sea salt fries 12 BRATWURST pickled slaw, dijonnaise, paprika ketchup 9 TRADITIONAL SCHNITZEL German potato salad, mustard vinaigrette 24 DÖNER ribeye or chicken, tzatziki, grilled jalapeños, arugula, tomato, onions 18 SAUSAGEFEST sausage smorgasbord, kraut, roasted potatoes, mustard, pickles 24 MONSTER PRETZEL stout beer cheese 14 SHAREABLE PULLED PORK SLIDERS apple slaw, blistered shishitos, marinated onions 3 for 12 HORSERADISH CAVIAR DIP housemade chips 9 LIPTAUER DIP house-made quark cheese, crudite 9 v BUTTERNUT SQUASH HUmmUS grilled pita, pumpkin seed oil 9 v TRUffLE DEVILED EGGS mustard vinaigrette, paprika 8 v BRIE BITES deep fried brie, maple syrup 10 v DACHA WINGS buffalo, bbq or sweet chili demi-glace sauce 6 for 12 MAINS & SALADS CLASSIC CAESAR garlic croutons, parmesan 14 v RIB EYE SKEWERS roasted fingerling potatoes, adjika, house salad 27 DACHA SALAD kale, mushrooms, kimchi, garlic crumbs, soy-sherry vinaigrette 14 vg CHICKEN SCHNITZEL SANDWICH braised purple kraut, havarti, dij onnaise, arugula 18 VEGGIE CROQUE sunny up egg, mushrooms, gruyere cheese, bechamel sauce 14 v GARLIC BUTTER SHRImp & CRAB TOAST sourdough, local tomatoes, old bay 17 BURGER peanut butter sauce, cheese, bacon, tomato, pickles, fries 17 DESSERTS CINNAMON SUGAR PRETZEL BITES dulce de leche dipping sauce 9 v NUTELLA PUDDING TO DIE FOR whipped cream, sprinkles 6 (v) vegetarian (vg) vegan (gf) gluten free 18% service charge is added to all checks; 20% for parties of 6 or more Cashless establishment DACHA BEER GARDEN SHAW WASHINGTON DC DRAFTS COCKTAILS single boot DACHNIK True Helles Lager 4.4% 9 | pint 18 GLÜHWEIN 10 Exclusively for us by DC Brau. -

High Treason: Essays on the History of the Red Army 1918-1938, Volume II

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE : HIG H TREASON: ESSAYS ON THE HISTORY OF TH E RED ARMY 1918-193 8 VOLUME I I AUTHOR . VITALY RAPOPOR T YURI ALEXEE V CONTRACTOR : CENTER FOR PLANNING AND RESEARCH, .INC . R . K . LAURINO, PROJECT DIRECTO R PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : VLADIMIR TREML, CHIEF EDITO R BRUCE ADAMS, TRANSLATOR - EDITO R COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 626- 3 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or i n part from funds provided by the National Council for Sovie t and East European Research . HIGH TREASO N Essays in the History of the Red Army 1918-1938 Volume I I Authors : Vitaly N . Rapopor t an d Yuri Alexeev (pseudonym ) Chief Editor : Vladimir Trem l Translator and Co-Editor : Bruce Adam s June 11, 198 4 Integrative Analysis Project o f The Center for Planning and Research, Inc . Work on this Project supported by : Tte Defense Intelligence Agency (Contract DNA001-80-C-0333 ) an d The National Council for Soviet and East European Studies (Contract 626-3) PART FOU R CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE RKK A Up to now we have spoken of Caligula as a princeps . It remains to discuss him as a monster . Suetoniu s There is a commandment to forgive our enemies , but there is no commandment to forgive our friends . L . Medic i Some comrades think that repression is the main thing in th e advance of socialism, and if repression does not Increase , there is no advance . Is that so? Of course it is not so .