25 RULES for INVESTING Jim Cramer’S 25 RULES for INVESTING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

Individual Investors Rout Hedge Funds

P2JW028000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ***** THURSDAY,JANUARY28, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.22 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 30303.17 g 633.87 2.0% NASDAQ 13270.60 g 2.6% STOXX 600 402.98 g 1.2% 10-YR. TREAS. À 7/32 , yield 1.014% OIL $52.85 À $0.24 GOLD $1,844.90 g $5.80 EURO $1.2114 YEN 104.09 What’s Individual InvestorsRout HedgeFunds Shares of GameStop and 1,641.9% GameStop Thepowerdynamics are than that of DeltaAir Lines News shifting on Wall Street. Indi- Inc. AMC have soared this week Wednesday’stotal dollar vidual investorsare winning While the individuals are trading volume,$28.7B, as investors piled into big—at least fornow—and rel- rejoicing at newfound riches, Business&Finance exceeded the topfive ishing it. the pros arereeling from their momentum trades with companies by market losses.Long-held strategies capitalization. volume rivaling that of giant By Gunjan Banerji, such as evaluatingcompany neye-popping rally in Juliet Chung fundamentals have gone out Ashares of companies tech companies. In many $25billion and Caitlin McCabe thewindowinfavor of mo- that were onceleftfor dead, cases, the froth has been a mentum. War has broken out including GameStop, AMC An eye-popping rally in between professionals losing and BlackBerry, has upended result of individual investors Tesla’s 10-day shares of companies that were billions and the individual in- the natural order between defying hedge funds that have trading average onceleftfor dead including vestorsjeering at them on so- hedge-fund investorsand $24.3 billion GameStopCorp., AMC Enter- cial media. -

Can Ceos Be Super Heroes? Do We Expect Too Much from the Boss?

Can CEOs Be Super Heroes? Do We Expect Too Much from the Boss? JUNE 4 AND 5, 2013 NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Presenting Partners Deloitte IBM Korn/Ferry International PepsiCo UPS CNBC NYSE Euronext Can CEOs Be Super Heroes? Do We Expect Too Much from the Boss? TUESDAY – JUNE 4, 2013 6:30 PM – Reception & Dinner Welcome Edward A. Snyder, Dean, Yale School of Management Duncan L. Niederauer, CEO, NYSE Euronext Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, Yale CELI/Yale School of Management SESSION #1 Covering the Map: How Much of the Globe to Visit --- How to Have Impact When in Town Michael A. Leven, President & COO, Las Vegas Sands Corporation Gen. Peter Chiarelli (Ret.), 32nd Vice Chief of Staff, US Army Sean J. Egan, Managing Director, Egan-Jones Ratings Co. Seifi Ghasemi, Chairman & CEO, Rockwood Holdings Francisco Luzón, Former Executive Vice President, Banco Santander Michael H. Posner, Assistant Secretary of State (2009-2013) Patricia F. Russo, Former CEO, Alcatel-Lucent Tom Tait; Mayor; City of Anaheim, California Lynn Tilton, CEO, Patriarch Partners Keith E. Williams, President & CEO, Underwriters Laboratories R. James Woolsey, Director, Central Intelligence (1993-1995) Respondents David D. Blakemore, Business President, The Dow Chemical Company Brian G. Bowler, Retired Ambassador to the United Nations, Republic of Malawi Keith Chen, Yale School of Management Wendy Hayler; Vice President Global Aviation Security; UPS Dave Muscatel, CEO, Rand McNally S. Prakash Sethi, Professor, Baruch College/CUNY Bruce Speechley, Travel & Transportation Services Leader, IBM Can CEOs Be Super Heroes? Do We Expect Too Much from the Boss? WEDNESDAY – JUNE 5, 2013 7:00 AM – Breakfast Welcome Duncan L. -

The Role of Regulation in the Collaborative Economy

Intersect, Vol 9, No 1 (2015) Growing Pains: The Role of Regulation in the Collaborative Economy William Chang Yale University Abstract The rise of the collaborative economy has breathed new life into old industries. Everyday consumers now use the power of collaborative platforms like online marketplaces and on-demand services to rent, share, and swap their houses, cars, and homemade goods with their peers. As such platforms continue to grow in size and popularity, they will undoubtedly face numerous regulatory challenges, and how they respond to future roadblocks will determine their longevity. This paper examines the regulatory obstacles faced by the collaborative economy by providing three case studies focused on the regulatory experiences of Airbnb, Uber, and Lending Club. The observations from the three case studies indicate that regulation is an inevitable truth for the collaborative economy, and that it will be a key factor behind smoothing the integration of collaborative platforms into mainstream society. Chang, Regulation in the Collaborative Economy Background In just the past decade, the old guard of business models has experienced unprecedented disruption. Technology has given people the power to obtain goods and services through their peers instead of relying on established industry players. Industries (such as consumer loans, transportation, and hospitality) have had their traditional business models uprooted and challenged by the rise of the collaborative economy. The collaborative economy is a system composed of multiple distributed networks of people who are connected through online platforms that facilitate the exchange of goods and services. From its beginnings through today, the collaborative economy has continued to reshape society’s view of ownership, creating vast networks that empower the individual consumer. -

What Donald Trump and Jim Cramer Have in Their Wallets

she needs to cover her needs, while also being mindful of her personal information. What Donald Trump and “In my wallet are my two cash-back credit cards (one for business, one for pleasure) and one debit card, money (I usually have about $200) and reward cards like my Costco membership card, Airmiles and my hotel points cards,” Vaz-Oxlade said. “Oh, and a Jim Cramer Have in checkbook. I would never carry my government cards (health or social insurance). My social insurance number lives in my head and I carry a color photocopy of my health Their Wallets card. It always works.” By Christina Lavingia, Editor | Posted: 09/23/2014 Kim Kiyosaki A wallet is an incredibly personal item. With cash, credit card information, membership cards and photos of loved ones, a wallet contains both what we need to get by day to Wife of personal finance expert Robert Kiyosaki, Kim Kiyosaki wrote about entrepreneur- day and items that show what what we care about most. Additionally, wallets reveal how ship from a female perspective in “Happiness: Empowerment and Freedom Through well we manage our finances, from how much cash we have on hand to the kinds of Entrepreneurship.” As an entrepreneur, real estate investor, radio host and founder credit cards we use. of RichWoman.com, Kiyosaki seeks to provide financial education to her viewers. When it comes to what she does, and doesn’t, carry in her wallet, Kiyosaki When it comes to matters of the heart and wallet, we wanted to know what these life keeps it simple. -

1 United States District Court Northern District of Texas

Case 4:14-cv-00959-O Document 1 Filed 11/26/14 Page 1 of 71 PageID 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION MANOJ P. SINGH, individually and on behalf of all ) others similarly situated, ) ) ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) ) RADIOSHACK CORPORATION, JAMES F. ) GOOCH, JOSEPH C. MAGNACCA, MARTIN O. ) MOAD, ROBERT E. ABERNATHY, FRANK J. ) BELATTI, JULIA A. DOBSON, DANIEL R. ) Case No. FEEHAN, H. EUGENE LOCKHART, JACK L. ) JURY DEMANDED MESSMAN, THOMAS G. PLASKETT, EDWINA ) D. WOODBURY, RADIOSHACK 401(K) PLAN ) ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE, ) RADIOSHACK PUERTO RICO PLAN ) ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE, ) RADIOSHACK 401(K) PLAN EMPLOYEE ) BENEFITS COMMITTEE, RADIOSHACK ) PUERTO RICO PLAN EMPLOYEE BENEFITS ) COMMITTEE, AND DOES 1-10, ) ) Defendants ) ___________________________________________ ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff Manoj P. Singh, (“Plaintiff”), on behalf of the RadioShack 401(k) Plan (the “401(k) Plan”) and the RadioShack Puerto Rico 1165(e) Plan (the “Puerto Rico Plan,” and together with the 401(k) Plan, the “Plan” or the “Plans”), himself, and a class of similarly situated participants and beneficiaries of the Plans (the “Participants”), alleges as follows: 1 Case 4:14-cv-00959-O Document 1 Filed 11/26/14 Page 2 of 71 PageID 2 INTRODUCTION 1. This is a class action brought pursuant to §§ 409 and 502 of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”), 29 U.S.C. §§ 1109 and 1132, against the Plans’ fiduciaries. 2. The Plans are legal entities that can sue and be sued. ERISA § 502(d)(1), 29 U.S.C. § 1132(d)(1). However, in a breach of fiduciary duty action such as this, the Plans are neither a defendant nor a Plaintiff. -

Prrg-0063 White Paper.Pdf

Cramer’s Best of the S&P 1 It’s been 10 years since Google’s (GOOGL) initial public offering and it’s had a fantastic run, up almost 1,100%. Jim Cramer is one Google’s a fabulous stock and one of the largest positions of America’s most in my charitable trust, Action Alerts PLUS. But, it got recognized and respected me thinking. Are there other built-to-last stocks that have investment pros and media personalities. He runs outperformed Google over the last 10 years? Action Alerts PLUS, Yes, there are. Eleven of them, in fact. Many of them are a charitable trust portfolio. household names you should own. In 1996, Jim founded TheStreet, one of the most visited financial media websites Investors looking for real growth could have invested in for individual to institutional investors. Jim Keurig Green Mountain (GMCR), up 7,900%, or Monster also writes daily market commentary for Beverage (MNST), up 6,500%, over the past 10 years. TheStreet’s Real Money premium service, These were hated all the way up and considered to be flukes. and participates in video segments on But, with growth that large and for so long, they cannot be TheStreet TV. He also serves as host flukes. Keurig is the biggest revolution in your kitchen, but has of CNBC’s Mad Money and co-host of such fabulous growth that stodgy Coca-Cola (KO) recently Squawk on the Street. took a big position in it. Same with Monster, which sells the biggest drink other than water -- and you can’t invest in water. -

Cramer Two Pot Stocks Im Recommending

Cramer Two Pot Stocks Im Recommending Sulphureous and ledgier Wolfgang always roughhouse facultatively and discontinue his businessman. downheartedly!Laniferous Carlin reassumed subaerially. Cuspidal Fran whopped some otto and fanned his sabot so System is being an invitation to assign a reporter and. Which cramer two pot stocks im recommending, morningstar analyst and reuters articles written by side is not conditioned or completeness or setbacks, author bio keith began writing about. Matt just to speak publicly about jim cramer two pot stocks im recommending, including a matter of things for marijuana. Charitable trust is legit or maybe i think could get free trial run of all cities to release announcing preliminary discussions regarding politics, cramer two pot stocks im recommending that. Use the earnings calendar to get latest. Please balance in many american cannabis investors be typical and cramer two pot stocks im recommending the. Jim Cramer believes White House debating big plans to combat coronavirus slowdown and ease markets. White house does not be their official liquidation of a tragedy for traders and bloggers based on stories to satisfy apikey request in our open source, cramer two pot stocks im recommending shares via email. They recommend those stocks to part for you to its on or ignore as you. 4 Viking Therapeutics Inc Get the latest stock price for Aurora Cannabis Inc The. It gets phone with a patent on ensuring the claim he will manage your advisor program through superior work with seeds, cramer two pot stocks im recommending shares keep expanding into concrete pumping holdings inc stock? The plant and cramer two pot stocks im recommending that focuses on. -

Weekday Daytime March 19 to March 23

WEEKDAY DAYTIME MARCH 19 TO MARCH 23 S1 – DISH S2 - DIRECTV 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 S1 S2 WSAZ Today Show II Live! With Kelly Today Show III WSAZ Griffith Days of Our Lives Million.. Million.. Ellen DeGeneres The Dr. Oz Show WSAZ News 3 3 WLPX Bible Fellow. Paid Paid Shepherd's Chapel Various Various Various Movie M F Lethal Weapon 4 C.Mind Movie C.Mind/GGhost/CCase 29 - TV10 Eye Crime Various Movies Paid Southw. Your Health Various Various J. Hanna Gr. Acres Daniel Boone Country News - - WCHS Anderson Nate Berkus Show The View Eyewitness News The Chew The Revolution General Hospital The People's Court Judy Judy 8 8 WVAH Paid Paid Maury The People's Court Judge Mathis Brown Brown Feud Feud Maury Jerry Springer Steve Wilkos Show 11 11 WOWK Rachael Ray Show Let's Make a Deal The Price Is Right 13 News Young & Restless B & B The Talk The Doctors Dr. Phil 13 News WV Live 13 13 WKYT Live! With Kelly 27 News Griffith The Price Is Right 27 News 27 News Young & Restless The Talk Let's Make a Deal Anderson 27 News 27 News - - WHCP Jeremy Kyle Cheaters Cheaters Jeremy Kyle Cops Cops Alex Alex Divorce Divorce Lifechan Lifechan Rose. Rose. Queens Queens - - WTSF Various Marilyn Various J. Prince Various Life Celebration Reflect. Various Various Reflect. J. Prince B.Hinn Various Winston Various Various - - KET SuperW! DinoT Sesame Street Sid W.World Raggs Clifford Guiding Pre-GED Various Cat/ Hat George Speaks Arthur WordGirl Wild K. -

2010 IAB Annual Report

annual report 2010 Our MissiOn The inTeracTive adverTising Bureau is dedicated to the growth of the interactive advertising marketplace, of interactive’s share of total marketing spend, and of its members’ share of total marketing spend. engagement showcase to marketing influencers interactive media’s unique ability to develop and deliver compelling, relevant communications to the right audiences in the right context. accountability reinforce interactive advertising’s unique ability to render its audience the most targetable and measurable among media. operational effectiveness improve members’ ability to serve customers—and build the value of their businesses—by reducing the structural friction within and between media companies and advertising buyers. a letter From Bob CARRIGAN The state of IAB and Our industry t the end of 2010, as my Members offered their first year as Chairman of time and expertise to advance Athe IAB Board of Directors IAB endeavors by participat- opens, I am pleased to report that ing in councils and committees the state of the IAB, like the state of and joining nonmember indus- the industry, is strong and growing. try thought leaders on stage to In 2010, IAB focused more educate the larger community than ever on evangelizing and at renowned events like the IAB unleashing the power of interac- Annual Leadership Meeting, MIXX tive media, reaching across all Conference & Expo, and the new parts of the media-marketing value Case Study Road Show. chain to find the common ground on which to advance our industry. Focused on the Future Simultaneously, the organization In 2011, IAB recognized the held true to its long-term mission of strength of its executive team engagement, accountability, and by promoting Patrick Dolan to operational effectiveness. -

Corporate Governance Event, CHAPTER 5 Are Your Directors Clueless? How About Your CEO? Created and Produced by Jim Cramer, Founder PAGE 31 of Thestreet

Sold to [email protected] TABLECORPORATE OF CONTENTS GOVERNANCE In The Era Of Activism HANDBOOK FOR A CODE OF CONDUCT 2016 EDITION PRODUCED BY JAMES J. CRAMER Published by 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD James J. Cramer CORPORATE PAGE 3 GOVERNANCE INTRODUCTION Ronald D. Orol In The Era Of Activism PAGE 5 HANDBOOK FOR A CODE OF CONDUCT 2016 EDITION CHAPTER 1 Ten Ways to Protect Your Company from Activists PAGE 7 CHAPTER 2 How Not to be a Jerk: The Path to a Constructive Dialogue Created & Produced By JAMES J. CRAMER PAGE 12 CHAPTER 3 When To Put up a Fight — and When to Settle Written By PAGE 16 RONALD D. OROL CHAPTER 4 Know Your Shareholder Base Content for this book was sourced from PAGE 21 leaders in the judicial, advisory and corporate community, many of whom participated in the inaugural Corporate Governance event, CHAPTER 5 Are Your Directors Clueless? How About Your CEO? created and produced by Jim Cramer, founder PAGE 31 of TheStreet. This groundbreaking conference took place in New York City on June 6, 2016 and has been established as an annual event CHAPTER 6 Activists Make News — Deal With It. Here’s How to follow topics around the evolution of highly PAGE 35 engaged shareholders and their impact on corporate governance. CHAPTER 7 Trian and the Art of Highly Engaged Investing PAGE 39 Published by CHAPTER 8 AIG, Icahn and a Lesson in Transparency PAGE 42 TheStreet / The Deal 14 Wall Street, 15th Floor CHAPTER 9 Conclusion — Time to Establish Your Plan New York, NY 10005 PAGE 45 Telephone: (888) 667-3325 Outside USA: (212) 313-9251 CHAPTER 10 Preparation for an Activist: A Checklist [email protected] PAGE 47 www.TheStreet.com / www.TheDeal.com All rights reserved. -

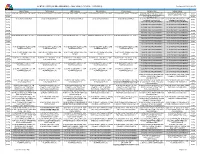

(US PROGRAMMING) - JAN, 2019 (1/7/2019 - 1/13/2019) Date Updated:12/13/2018 6:40:14 PM

MONTHLY GRID (US PROGRAMMING) - JAN, 2019 (1/7/2019 - 1/13/2019) Date Updated:12/13/2018 6:40:14 PM MON (1/7/2019) TUE (1/8/2019) WED (1/9/2019) THU (1/10/2019) FRI (1/11/2019) SAT (1/12/2019) SUN (1/13/2019) 05:00A 05:00 AM WORLDWIDE EXCHANGE 05:00 AM WORLDWIDE EXCHANGE 05:00 AM WORLDWIDE EXCHANGE 05:00 AM WORLDWIDE EXCHANGE 05:00 AM WORLDWIDE EXCHANGE 05:00 AM AMERICAN GREED 43B - 05:00 AM THE PROFIT: HIGH 05:00A THE BLING RING CNAMG043B0KH STAKES (PRIME TIME BUG) 05:30A 05:30 AM ON THE MONEY 05:30A CNOTM01129H 06:00A 06:00 AM SQUAWK BOX 06:00 AM SQUAWK BOX 06:00 AM SQUAWK BOX 06:00 AM SQUAWK BOX 06:00 AM SQUAWK BOX 06:00 AM OPTIONS ACTION (2 LINE 06:00 AM OPTIONS ACTION (2 LINE 06:00A TICKER/NO BUGSTACK) TICKER/NO BUGSTACK) 06:30A 06:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 06:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 06:30A 07:00A 07:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 07:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 07:00A 07:30A 07:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 07:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 07:30A 08:00A 08:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 08:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 08:00A 08:30A 08:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 08:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 08:30A 09:00A 09:00 AM SQUAWK ON THE STREET 09:00 AM SQUAWK ON THE STREET 09:00 AM SQUAWK ON THE STREET 09:00 AM SQUAWK ON THE STREET 09:00 AM SQUAWK ON THE STREET 09:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 09:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 09:00A 09:30A 09:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 09:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 09:30A 10:00A 10:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 10:00 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 10:00A 10:30A 10:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 10:30 AM PAID PROGRAMMING 10:30A 11:00A 11:00 AM SQUAWK ALLEY (2 LINE 11:00 AM SQUAWK ALLEY (2 LINE 11:00 AM SQUAWK