El Tren Fantasma: Arcs of Sound and the Acoustic Spaces of Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd

productions 2020 Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd. is a leading international television production company with an outstanding reputation for producing and distributing innovative factual entertainment, history and travel led programmes. The company was set up by Ian Cross in 1988; and it is now one of the longest established independent production companies under continuous ownership in the United Kingdom. Pilot has produced over 500 hours of multi-genre programming covering subjects as diverse as history, food and sport. Its award winning Globe Trekker series, broadcast in over 20 countries, has a global audience of over 20 million. Pilot Productions has offices in London and Los Angeles. CONTENTS Mission Statement 3 In Production 4 New 6 Tough Series 8 Travelling in the 1970’s 10 Specials 11 Empire Builders 12 Ottomans vs Christians 14 History Specials 18 Historic Walks 20 Metropolis 21 Adventure Golf 22 Great Railway Journeys of Europe 23 The Story Of... Food 24 Bazaar 26 Globe Trekker Seasons 1-5 28 Globe Trekker Seasons 6-11 30 Globe Trekker Seasons 12-17 32 Globe Trekker Specials 34 Globe Trekker Around The World 36 Pilot Globe Guides 38 Destination Guides 40 Other Programmes 41 Short Form Content 42 DVDs and music CDs 44 Study Guides 48 Digital 50 Books 51 Contacts 52 Presenters 53 2 PILOT PRODUCTIONS 2020 MISSION STATEMENT Pilot Productions seeks to inspire and educate its audience by creating powerful television programming. We take pride in respecting and promoting social, environmental and personal change, whilst encouraging others to travel and discover the world. Pilot’s programmes have won more than 50 international awards, including six American Cable Ace awards. -

Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-14-2016 Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band Jason M. Silveira Justin Cusick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Concert Band; Silveira, Jason M.; and Cusick, Justin, "Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band" (2016). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1779. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1779 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Concert Band "Road Trip!" Jason M. Silveira, conductor Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Ford Hall Thursday, April 14th, 2016 8:15 pm Program New England Tritych (1957) William Schuman I. Be Glad Then, America (1910–1992) II. When Jesus Wept 17' III. Chester More Old Wine in New Bottles (1977) Gordon Jacob I. Down among the Dead Men (1895–1984) II. The Oak and the Ash 11' III. The Lincolnshire Poacher IV. Joan to the Maypole Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Intermission Four Cornish Dances (1966/1975) Malcolm Arnold I. Vivace arr. Thad Marciniak II. Andantino (1921–2006) III. Con moto e sempre senza parodia 10' IV. Allegro ma non troppo Homecoming (2008) Alex Shapiro (b. 1962) 7' The Klaxon (1929/1984) Henry Fillmore arr. Frederick Fennell (1881–1956) 3' Jason M. Silveira is assistant professor of music education at Ithaca College. He received his Bachelor of Music and Master of Music degrees in music education from Ithaca College, and his Ph. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

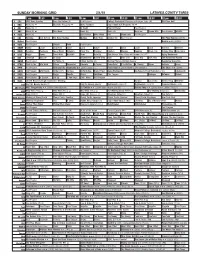

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

1. Walk the Moon

Label Copy CD1 1. WALK THE MOON - Shut Up And Dance (Petricca / Ray / Waugaman / Maiman / Berger / McMahon) Published by W B Music Corp / Warner/Chappell North America Limited / Ryan McMahon Publishing Produced by Tim Pagnotta (P) 2014 RCA Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment USRC11401949 3.17 2. Bastille – Pompeii (Smith) Published by Universal Music Publishing Ltd Produced by Mark Crew (P) 2013 Virgin Records Ltd. Licensed courtesy of Universal Music Group GBAAA1200795 3.34 3. Metro Station - Shake It (Cyrus / Musso / Healy / Improgo) Published by EMI Music Publishing Limited (MCPS/BIEM) Produced by S*A*M / Sluggo (P) 2007 Columbia Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment USSM10800776 3.02 4. Sam Sparro - Black & Gold (Falson / Rogg) Published by EMI Music Publishing Ltd. Produced by Jesse Rogg & Sam Sparro (P) 2007 Universal Island Records Ltd. A Universal Music Company. Licensed courtesy of Universal Music Group GBUM70800413 3.30 5. Owl City - Fireflies (Young) Published by Ocean City Park (Universal Music Corp.) ASCAP / Universal/MCA Music Limited Produced by Adam Young (P) 2009 Universal Republic Records, a division of UMG Recordings, Inc. Licensed courtesy of Universal Music Group USUM70916628 3.14 6. Orson - No Tomorrow (Rachild / Astasio / Cano / Pebworth / Jen / Roentgen) Published by Universal Music Publishing Ltd. Produced by Noah Shain, Orson and Chad Rachild (P) 2006 Mercury Records Limited Licensed courtesy of Universal Music Group GBUM70500865 2.48 7. Just Jack - Starz In Their Eyes (Allsopp) Published by Just Jack Ltd./Universal Music Publishing Ltd Produced by Jack Allsopp & Jay Reynolds (P) 2006 Mercury Records Limited Licensed courtesy of Universal Music Group GBUM70604909 3.10 8. -

Adidas Originals Unite All Originals Press

Very few DJs can jump from club sets to high-profile festival performances, to Kanye West’s larger- than-life stadium shows with ease. In today’s DJ culture, A-Trak holds a truly unique place. He and partner Nick Catchdubs founded America’s most trendsetting new label, Fool’s Gold, launching the careers of artists such as Kid Sister and Kid Cudi. Fool’s Gold’s mission to merge all aspects of club music was already outlined in Trizzy’s original mixtape manifesto, Dirty South Dance, which set the tone for his own production. He is now one of the most sought-after remixers in electronic music, and his remixes for the likes of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Boys Noize have become undeniable mainstays in DJ sets the world over. 2009 saw the release of two critically acclaimed DJ mixes, Infinity +1 and Fabriclive 45, as well as the birth of Duck Sauce, his collaboration with Armand Van Helden. The duo’s radio smash “aNYway” cemented itself as the dance anthem of the year, A-Trak’s first true chart- topper with two videos in international rotation and across-the-board support from Pete Tong to Busy P, David Guetta to 2manydjs. Duck Sauce’s 2010 follow up “Barbra Streisand” was even bigger, a whistling pop sensation that accumulated over 60 million YouTube views of its star-studded video while hitting platinum heights around the globe. They even covered it on X-Factor and Glee! Not bad for a kid whom many viewed as a 90’s turntablism prodigy. -

Mustang Echoes “The Voice of MHS”

Mustang Echoes “The Voice of MHS” Dates to Remember: September 26th Homecoming parade (6:00) Homecoming game vs. Reading (7:30) September 27th Homecoming dance (9:00-12:00) October 15th PSAT Homecoming 2008: Cap & Gown assembly A Day at the Zoo October 22nd Johnny Carpenter Early Release (1:00) It’s that time of year again…Homecoming! The Madeira Mustangs are poised and ready to demolish the Reading Blue Devils on our home turf. Put aside all the October 31st hype and small talk, and our Mustangs are ready for anything. This year’s team has changed drastically…new coaching staff, new offense, tougher defense—all adding up Senior picture, memory to what many experts claim will be the formula for a winning team. page, quote, and baby The 2008 Mustangs were hit hard by graduation, losing some very talented picture due athletes, but this year’s senior class could prove to be even stronger. With starting halfback Will McClanahan coming back from a great season last year, the ‘Stang November 7th running game looks to tear up the turf once again. Also, starting quarterback Kyle Voisard looks to lead the team to a huge victory Homecoming night. Kyle will be No school looking to connect to his reliable and talented wide receivers Chris Ballweg, David Wood, and Patrick O’Leary. The big dogs who will provide Will and Kyle all the November 20th-22nd protection they need include Brian Wagers, Cole Hayes, Rob Braun, and Brad Rusk. Fall play, Anne Frank After interviewing several of the varsity players, they want nothing less than the best out of everyone on game night. -

Luxury Rail Journeys

RAIL JOURNEYS LUXURY TRAIN TRAVEL A WORLD JOURNEYS COLLECTION 2019/2020 VIA Rail Rocky Mountaineer New England’s Autumn Colours Belmond Royal Scotsman Belmond Grand Hibernian Golden Eagle Venice Simplon-Orient-Express Renfe Luxury Trains of Spain Shangri-La Express Maharajas’ Express Deccan Odyssey Palace on Wheels Eastern & Oriental Express Rovos Rail The Blue Train CONTENTS 2 JOURNEY WITH US 20 The Ultimate Journey 3 TAILOR-MADE TRAVEL 21 A Trail of Two Oceans 22 The Namibia Journey 4 GOLDEN EAGLE LUXURY TRAINS 5 China & Tibet Rail Discovery 23 THE BLUE TRAIN 6 Trans-Siberian Express 24 LUXURY TRAINS OF INDIA 7 Quest for the Northern Lights 26 Maharajahs’ Express: Indian Panorama 8 RENFE LUXURY TRAINS OF SPAIN 27 Deccan Odyssey: Delhi to Mumbai 9 El Transcantabrico Clasico 28 Palace on Wheels 10 Al Andalus 29 ROCKY MOUNTAINEER 11 BELMOND 30 Journey Through the Clouds Explorer 12 Venice Simplon-Orient-Express 31 First Passage to the West Highlights 13 Belmond Royal Scotsman 32 VIA RAIL 14 Belmond Grand Hibernian 33 Trans Canada Rail Adventure 15 Eastern & Oriental Express 34 Eastern Canada by Rail 16 ROVOS RAIL 35 NEW ENGLAND’S AUTUMN COLOURS 17 Pretoria to Cape Town 18 Pretoria to Victoria Falls 36 GIVING BACK 19 The African Golf Collage 37 TERMS & CONDITIONS JOURNEY WITH US At World Journeys our mission is simple: we design journeys that we, as travellers, would undertake ourselves. In our youth, we travelled the world on a budget, battling bureaucracy and language barriers to prove we could do it on our own. In later years we found, like many others, that we had less time to travel, let alone the luxury of planning our experiences. -

The British Overseas Railways Historical Trust Library Catalogue (2011 Provisional Edition)

THE BRITISH OVERSEAS RAILWAYS HISTORICAL TRUST LIBRARY CATALOGUE (2011 PROVISIONAL EDITION) This is an update of the first attempt at listing the books which BORHT holds. Members wishing to access the library are requested to contact Mostyn Lewis and arrange that a committee member will be at Greenwich to grant access. Books are not at present available for loan (some are allocated to a future lending library which awaits manpower for its organisation and resolution of copyright issues resulting from the EU Directive), but a photocopier is available on site. SECTION 1 – GENERAL, UK AND EUROPE Bibliographies and Archive Lists Alpin, Hugh A. Catalogue of the Lomonossoff Collections, 1988 (2009/36/14) Cottrell. Handbook of Early Railway Books 1893 (Reprint) Durrant, A.E. Index to African References in the Locomotive Magazine, Beyer, Peacock Quarterly Review, Henschel Hefte/Review, Rhodesia Railway Circle Newsletter. Cape Town: The Railway History Group. Ottley. Bibilography of British Railway History, 1965 edn and 2nd Supplement Richards, Tom. Was your Grandfather a Railwayman?, 4th edn 2002. Wildish, Gerald. International Railway Index, ver 6.0 (CD) (2009/41) Williamson, A A. Descriptive Notes and Illustrated Catalogue: Collection of Historic Railway Locomotive Drawings Presented to the Museums by the Vulcan Foundry Ltd, City of Liverpool Museums, c.1960 General The Civil Engineer at War, Vol 2 Docks and Harbours, 1948 (20102/20) Fodor’s Railways of the World New York: 1977 Great Railway Journeys of the World, (BBC 1981) 1982 edn (2007/26/52) King’s of Steam 2004 reprint of Beyer Peacock booklet of 1945. LMA Handbook, 1949 Tramways and Electric Railways in the Nineteenth Century. -

2019 Tours & Day Trips

2019 TOURS & DAY TRIPS Book by phone on 01625 425060 Book at: The Coach Depot, Snape Road, Macclesfield, SK10 2NZ. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 1 - 3 2019 HOLIDAYS MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR ......................................................................................................................... 3 CAMELLIAS & KEW GARDENS ORCHID FESTIVAL ................................................................................. 4 THE DELIGHTS OF SIDMOUTH ................................................................................................................... 5 THE ISLES OF SCILLY ............................................................................................................................. 6 - 7 RAIL & SAIL – COCKERMOUTH & THE NORTH LAKES ............................................................................. 8 SPRINGTIME GARDENS AT HIGHGROVE .................................................................................................. 9 SPRINGTIME IN THE ISLANDS OF MALTA ........................................................................................ 10 - 11 THE GARDENS OF CORNWALL – THE LOST GARDENS OF HELIGAN & THE EDEN PROJECT .......... 12 WEEKEND BREAK – THE HISTORIC CITY OF LINCOLN ......................................................................... 13 THE CHANNEL ISLES BY AIR – JERSEY & ST BRELADES BAY .............................................................. 14 DORSET