Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd

productions 2020 Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd. is a leading international television production company with an outstanding reputation for producing and distributing innovative factual entertainment, history and travel led programmes. The company was set up by Ian Cross in 1988; and it is now one of the longest established independent production companies under continuous ownership in the United Kingdom. Pilot has produced over 500 hours of multi-genre programming covering subjects as diverse as history, food and sport. Its award winning Globe Trekker series, broadcast in over 20 countries, has a global audience of over 20 million. Pilot Productions has offices in London and Los Angeles. CONTENTS Mission Statement 3 In Production 4 New 6 Tough Series 8 Travelling in the 1970’s 10 Specials 11 Empire Builders 12 Ottomans vs Christians 14 History Specials 18 Historic Walks 20 Metropolis 21 Adventure Golf 22 Great Railway Journeys of Europe 23 The Story Of... Food 24 Bazaar 26 Globe Trekker Seasons 1-5 28 Globe Trekker Seasons 6-11 30 Globe Trekker Seasons 12-17 32 Globe Trekker Specials 34 Globe Trekker Around The World 36 Pilot Globe Guides 38 Destination Guides 40 Other Programmes 41 Short Form Content 42 DVDs and music CDs 44 Study Guides 48 Digital 50 Books 51 Contacts 52 Presenters 53 2 PILOT PRODUCTIONS 2020 MISSION STATEMENT Pilot Productions seeks to inspire and educate its audience by creating powerful television programming. We take pride in respecting and promoting social, environmental and personal change, whilst encouraging others to travel and discover the world. Pilot’s programmes have won more than 50 international awards, including six American Cable Ace awards. -

David Toop Ricocheting As a 1960S Teenager Between Blues Guitarist

David Toop Ricocheting as a 1960s teenager between blues guitarist, art school dropout, Super 8 film loops and psychedelic light shows, David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music and materials since 1970. This practice encompasses improvised music performance (using hybrid assemblages of electric guitars, aerophones, bone conduction, lo-fi archival recordings, paper, sound masking, water, autonomous and vibrant objects), writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations and opera (Star-shaped Biscuit, performed in 2012). It includes seven acclaimed books, including Rap Attack (1984), Ocean of Sound (1995), Sinister Resonance (2010) and Into the Maelstrom (2016), the latter a Guardian music book of the year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Music Book Prize. Briefly a member of David Cunningham’s pop project The Flying Lizards (his guitar can be heard sampled on “Water” by The Roots), he has released thirteen solo albums, from New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments on Brian Eno’s Obscure label (1975) and Sound Body on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label (2006) to Entities Inertias Faint Beings on Lawrence English’s ROOM40 (2016). His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism and ritual - released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows (2016) - were called by The Wire a “tsunami of weirdness” while Entities Inertias Faint Beings was described in Pitchfork as “an album about using sound to find one’s own bearings . again and again, understated wisps of melody, harmony, and rhythm surface briefly and disappear just as quickly, sending out ripples that supercharge every corner of this lovely, engrossing album.” In the early 1970s he performed with sound poet Bob Cobbing, butoh dancer Mitsutaka Ishii and drummer Paul Burwell, along with key figures in improvisation, including Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Georgie Born, Hugh Davies, John Stevens, Lol Coxhill, Frank Perry and John Zorn. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Luxury Rail Journeys

RAIL JOURNEYS LUXURY TRAIN TRAVEL A WORLD JOURNEYS COLLECTION 2019/2020 VIA Rail Rocky Mountaineer New England’s Autumn Colours Belmond Royal Scotsman Belmond Grand Hibernian Golden Eagle Venice Simplon-Orient-Express Renfe Luxury Trains of Spain Shangri-La Express Maharajas’ Express Deccan Odyssey Palace on Wheels Eastern & Oriental Express Rovos Rail The Blue Train CONTENTS 2 JOURNEY WITH US 20 The Ultimate Journey 3 TAILOR-MADE TRAVEL 21 A Trail of Two Oceans 22 The Namibia Journey 4 GOLDEN EAGLE LUXURY TRAINS 5 China & Tibet Rail Discovery 23 THE BLUE TRAIN 6 Trans-Siberian Express 24 LUXURY TRAINS OF INDIA 7 Quest for the Northern Lights 26 Maharajahs’ Express: Indian Panorama 8 RENFE LUXURY TRAINS OF SPAIN 27 Deccan Odyssey: Delhi to Mumbai 9 El Transcantabrico Clasico 28 Palace on Wheels 10 Al Andalus 29 ROCKY MOUNTAINEER 11 BELMOND 30 Journey Through the Clouds Explorer 12 Venice Simplon-Orient-Express 31 First Passage to the West Highlights 13 Belmond Royal Scotsman 32 VIA RAIL 14 Belmond Grand Hibernian 33 Trans Canada Rail Adventure 15 Eastern & Oriental Express 34 Eastern Canada by Rail 16 ROVOS RAIL 35 NEW ENGLAND’S AUTUMN COLOURS 17 Pretoria to Cape Town 18 Pretoria to Victoria Falls 36 GIVING BACK 19 The African Golf Collage 37 TERMS & CONDITIONS JOURNEY WITH US At World Journeys our mission is simple: we design journeys that we, as travellers, would undertake ourselves. In our youth, we travelled the world on a budget, battling bureaucracy and language barriers to prove we could do it on our own. In later years we found, like many others, that we had less time to travel, let alone the luxury of planning our experiences. -

Matt's Gallery Presents TAPS

Matt ’s Galle ry presents TAPS: Improvisations with Paul Burwell at Dilston Grove (1 ) Southwark Park, London se16 2dd 17 –19 September 2010 t (020) 8983 1771 Press release Friday Continuous film screening 2–7pm. Performances by Melissa Castagnetto 7pm, Oren Marshall & Steve Noble 8pm, Yol 9pm Saturday Continuous film screening 2–7pm. Performances by Shaun Caton 2 –7pm, William Cobbing 7pm, Kaffe Matthews 8pm, Juneau Projects 9pm Sunday Continuous film screening 2 –7pm. Intermittent performance by Ryuzo Fukuhara 2 –7pm. Sunday closing view with final event including performance by Ansuman Biswas 6–8pm. (1) Dilston Grove is at the South - Paul Burwell was infamous for his exuberant fusions of fine-art installation, west corner of Southwark Park percussion and explosive performance. He was a staunch advocate of, and Train: Canada Water, Jubilee & Over - ground lines passionate participant in, all forms of experimental art. TAPS: Improvisa - Bus: 1, 47, 188, 225, 381, C10, P12 tions with Paul Burwell , realised by Anne Bean, Robin Klassnik and Richard (2) Live performers Wilson embodies his prolific practice. Ansuman Biswas | Melissa Castag - Over the course of three days TAPS will combine film, installation netto | Shaun Caton | William Cob - bing | Ryuzo Fukuhara | Juneau and performance, portraying layers of interpretation from more than 80 Projects | Oren Marshall & Steve invited collaborators, in response to Burwell’s poem ‘Adventures in the Noble | Kaffe Matthews | Yol House of Memory’. The poem arose from improvisations by Anne Bean and (3) Composite film, contributing Paul Burwell in preparation for William Burroughs’s Final Academy at Ritzy, artists Mark Anderson with Nick Sales & Jony Easterby | Anne Bean | London in 1982, where improvised words were written on huge sheets of Steve Beresford * | Steven Berkoff | flash paper which were ignited as they were sung. -

The British Overseas Railways Historical Trust Library Catalogue (2011 Provisional Edition)

THE BRITISH OVERSEAS RAILWAYS HISTORICAL TRUST LIBRARY CATALOGUE (2011 PROVISIONAL EDITION) This is an update of the first attempt at listing the books which BORHT holds. Members wishing to access the library are requested to contact Mostyn Lewis and arrange that a committee member will be at Greenwich to grant access. Books are not at present available for loan (some are allocated to a future lending library which awaits manpower for its organisation and resolution of copyright issues resulting from the EU Directive), but a photocopier is available on site. SECTION 1 – GENERAL, UK AND EUROPE Bibliographies and Archive Lists Alpin, Hugh A. Catalogue of the Lomonossoff Collections, 1988 (2009/36/14) Cottrell. Handbook of Early Railway Books 1893 (Reprint) Durrant, A.E. Index to African References in the Locomotive Magazine, Beyer, Peacock Quarterly Review, Henschel Hefte/Review, Rhodesia Railway Circle Newsletter. Cape Town: The Railway History Group. Ottley. Bibilography of British Railway History, 1965 edn and 2nd Supplement Richards, Tom. Was your Grandfather a Railwayman?, 4th edn 2002. Wildish, Gerald. International Railway Index, ver 6.0 (CD) (2009/41) Williamson, A A. Descriptive Notes and Illustrated Catalogue: Collection of Historic Railway Locomotive Drawings Presented to the Museums by the Vulcan Foundry Ltd, City of Liverpool Museums, c.1960 General The Civil Engineer at War, Vol 2 Docks and Harbours, 1948 (20102/20) Fodor’s Railways of the World New York: 1977 Great Railway Journeys of the World, (BBC 1981) 1982 edn (2007/26/52) King’s of Steam 2004 reprint of Beyer Peacock booklet of 1945. LMA Handbook, 1949 Tramways and Electric Railways in the Nineteenth Century. -

Pluralism in Contemporary Improvised Concert Music

Aalborg Universitet Pluralism in contemporary improvised concert music Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl Published in: Proceedings of the Vth European Music Therapy Congress in Castel Dell'Ovo, Napoli, Italy 20. - 24.4. 2001 Publication date: 2002 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Bergstrøm-Nielsen, C. (2002). Pluralism in contemporary improvised concert music. In D. Alridge, & J. Fachner (Eds.), Proceedings of the Vth European Music Therapy Congress in Castel Dell'Ovo, Napoli, Italy 20. - 24.4. 2001 (pp. 136-148) http://www.musictherapyworld.de General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 28, 2021 PLURALISM IN CONTEMPORARY IMPROVISED CONCERT MUSIC By Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen Paper from the 5 th European Music Therapy Congress, Napoli 20-24 April 2001. -

2019 Tours & Day Trips

2019 TOURS & DAY TRIPS Book by phone on 01625 425060 Book at: The Coach Depot, Snape Road, Macclesfield, SK10 2NZ. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 1 - 3 2019 HOLIDAYS MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR ......................................................................................................................... 3 CAMELLIAS & KEW GARDENS ORCHID FESTIVAL ................................................................................. 4 THE DELIGHTS OF SIDMOUTH ................................................................................................................... 5 THE ISLES OF SCILLY ............................................................................................................................. 6 - 7 RAIL & SAIL – COCKERMOUTH & THE NORTH LAKES ............................................................................. 8 SPRINGTIME GARDENS AT HIGHGROVE .................................................................................................. 9 SPRINGTIME IN THE ISLANDS OF MALTA ........................................................................................ 10 - 11 THE GARDENS OF CORNWALL – THE LOST GARDENS OF HELIGAN & THE EDEN PROJECT .......... 12 WEEKEND BREAK – THE HISTORIC CITY OF LINCOLN ......................................................................... 13 THE CHANNEL ISLES BY AIR – JERSEY & ST BRELADES BAY .............................................................. 14 DORSET -

YOUR WORLD by TRAIN in 2020 CONTENTS WELCOME ABOARD! It’S with Great Excitement I Offer Our Welcome Aboard!

YOUR WORLD BY TRAIN IN 2020 CONTENTS WELCOME ABOARD! It’s with great excitement I offer our Welcome Aboard! .....................................................................3 program for 2020, featuring a few of The Railway Adventures Story & What They Say .....................4 our favourites and an ever-growing list of new adventures to a variety of Why Travel With Us? ................................................................5 wonderful destinations far and wide. What Else We Offer & Fitness Ratings .....................................6 Tour Leaders .............................................................................7 2019 was a big year for Railway Adventures and the benefits in 2020 AUSTRALIA and beyond will be yours – a new office, operational structure and Outback Queensland ................................................................8 accreditation as a full-service Travel The Queensland Coast by Rail, Road, Air and Sea ..................9 Agent, new tour leaders added to Tasmania by Rail, Road and River ..........................................10 our stable and new partnerships with other great rail providers means Victoria by Rail and Road .......................................................11 our travellers now have more choice Golden West Rail Tour ............................................................12 than ever before. We can now look after all your travel needs Mudgee Weekend Escape .....................................................13 – your one-stop travel shop, from tour bookings to -

The Hugh Davies Collection: Live Electronic Music and Self-Built Electro-Acoustic Musical Instruments, 1967–1975

Science Museum Group Journal The Hugh Davies Collection: live electronic music and self-built electro-acoustic musical instruments, 1967–1975 Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Dr James Mooney 03-01-2017 Cite as 10.15180; 170705 Research The Hugh Davies Collection: live electronic music and self-built electro-acoustic musical instruments, 1967–1975 Published in Spring 2017, Sound and Vision Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170705 Abstract The Hugh Davies Collection (HDC) at the Science Museum in London comprises 42 items of electronic sound apparatus owned by English experimental musician Hugh Davies (1943–2005), including self-built electro-acoustic musical instruments and modified sound production and manipulation hardware. An early proponent of ‘live electronic music’ (performed live on stage rather than constructed on magnetic tape in a studio), Davies’s DIY approach shaped the development of experimental and improvised musics from the late 1960s onwards. However, his practice has not been widely reported in the literature, hence little information is readily available about the material artefacts that constituted and enabled it. This article provides the first account of the development of Davies’s practice in relation to the objects in the HDC: from the modified electronic sound apparatus used in his early live electronic compositions (among the first of their kind by a British composer); through the ‘instrumental turn’ represented by his first self-built instrument, Shozyg I (1968); to his mature practice, where self-built instruments like Springboard Mk. XI (1974) replaced electronic transformation as the primary means by which Davies explored new and novel sound-worlds. -

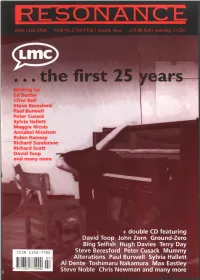

+ Double CD Featuring David Toop John Zorn Ground-Zero Bing

W riting by Ed Baxter Clive Bell Steve Beresford Paul Burwell Peter Cusack Sylvia Hallett Maggie Nicols Annabel Nicolson Robin Ramsay Richard Sanderson Richard Scott David Toop - and many more + double CD featuring David Toop John Zorn Ground-Zero Bing Selfish Hugh Davies Terry Day ISSN 1352-772X Steve Beresford Peter Cusack Mummy 977135277299007 Alterations Paul Burwell Sylvia Hallett Al Dente Toshimaru Nakamura Max Eastley 9 771352 772990 Steve Noble Chris Newman and many more ances. O ne night I turned up and poked Maggie telling a story about a dancing my nose in to see what was happening and My favourite LMC moment female slug in the candlelight and going was lured in by a man playing serene C A R O L I N E K R A A B E L completely beyond improvisation into a meditational music by applying a piece of sort of egoless free association that held expanded polystyrene to a rotating glass the listeners embarrassed and enthralled, table [B a rry Leigh]. Max Eastley’s long almost frightened. bowed instruments and mechanical opera Keiji Haino’s acoustic percussion solo at characters were as amazing to see as to one LMC festival. Haco’s microphone hear. I remember a performance by what feedback in a teapot - along with Charles may or may not have been the Bow Hayward’s Doppler on a cheap cassette Gamelan, where Paul Burwell and a machine, the only LMC performance I’ve woman coated each other in gloss paint - personally witnessed that really dealt in any having found it hard enough to clean my way with the BASIC paradoxes of own body o f a coat o f acrylic after an electricity and music. -

The Wexas Travel Magazine Vol 45 » No 1 » 2015 £6.95 Editorialissue 1 / 2015 PLACES

the wexas travel magazine vol 45 » no 1 » 2015 £6.95 editorialissue 1 / 2015 PLACES OF POETRYIt’s a fine tradition, the poetry of a place as well as poetry can, and place, and an ancient one. In his one of the most visually striking book Walking Home, Armitage features in this issue is a sultry AS I FINISHED WRITING UP MY refers to Homer’s epic poem, the photo essay about tango in the interview with Simon Armitage Odyssey, as one of the greatest Colombian city of Medellín, which for this issue, my mind was works of western literature, and has the strongest tango culture filled with a strong memory of one that ‘could also be described outside of Argentina. Medellín is an evening spent by the South as one of the first pieces of travel also gaining a reputation as the Bank. It’s a happy one. There writing.’ And although we don’t ‘world capital of poetry’ – declared were hundreds of us out there, Amy Sohanpaul run pieces written entirely in as such by the many poets that waiting for some helicopters considers the verse in Traveller – I’m thinking congregate there annually for to whirr into view. They arrived merits of verse now perhaps we should – we do The International Poetry Festival with the sunset, looking slightly over prose like it when a feature doesn’t use of Medellín. The festival was born sinister as helicopters of a certain ‘the language of information’ in 1991, when Medellín was the size sometimes do, ominous and instead conveys the essence most violent city in the world.