1 Chapter 1 Introduction the Books We Read

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

'Ways of Seeing': the Tasmanian Landscape in Literature

THE TERRITORY OF TRUTH and ‘WAYS OF SEEING’: THE TASMANIAN LANDSCAPE IN LITERATURE ANNA DONALD (19449666) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2013 ii iii ABSTRACT The Territory of Truth examines the ‘need for place’ in humans and the roads by which people travel to find or construct that place, suggesting also what may happen to those who do not find a ‘place’. The novel shares a concern with the function of landscape and place in relation to concepts of identity and belonging: it considers the forces at work upon an individual when they move through differing landscapes and what it might be about those landscapes which attracts or repels. The novel explores interior feelings such as loss, loneliness, and fulfilment, and the ways in which identity is derived from personal, especially familial, relationships Set in Tasmania and Britain, the novel is narrated as a ‘voice play’ in which each character speaks from their ‘way of seeing’, their ‘truth’. This form of narrative was chosen because of the way stories, often those told to us, find a place in our memory: being part of the oral narrative of family, they affect our sense of self and our identity. The Territory of Truth suggests that identity is linked to a sense of self- worth and a belief that one ‘fits’ in to society. The characters demonstrate the ‘four ways of seeing’ as discussed in the exegesis. ‘“Ways of Seeing”: The Tasmanian Landscape in Literature’ considers the way humans identify with ‘place’, drawing on the ideas and theories of critics and commentators such as Edward Relph, Yi-fu Tuan, Roslynn Haynes, Richard Rossiter, Bruce Bennett, and Graham Huggan. -

Study of Caste

H STUDY OF CASTE BY P. LAKSHMI NARASU Author of "The Essence of Buddhism' MADRAS K. V. RAGHAVULU, PUBLISHER, 367, Mint Street. Printed by V. RAMASWAMY SASTRULU & SONS at the " VAVILLA " PRESS, MADRAS—1932. f All Rights Reservtd by th* Author. To SIR PITTI THY AG A ROY A as an expression of friendship and gratitude. FOREWORD. This book is based on arfcioles origiDally contributed to a weekly of Madras devoted to social reform. At the time of their appearance a wish was expressed that they might be given a more permanent form by elaboration into a book. In fulfilment of this wish I have revised those articles and enlarged them with much additional matter. The book makes no pretentions either to erudition or to originality. Though I have not given references, I have laid under contribution much of the literature bearing on the subject of caste. The book is addressed not to savants, but solely to such mea of common sense as have been drawn to consider the ques tion of caste. He who fights social intolerance, slavery and injustice need offer neither substitute nor constructive theory. Caste is a crippli^jg disease. The physicians duty is to guard against diseasb or destroy it. Yet no one considers the work of the physician as negative. The attainment of liberty and justice has always been a negative process. With out rebelling against social institutions and destroying custom there can never be the tree exercise of liberty and justice. A physician can, however, be of no use where there is no vita lity. -

National Reconciliation Week Let’S Walk the Talk! 27 May – 3 June Let’S Walk the Talk!

National Reconciliation Week National Reconciliation Week Let’s walk the talk! 27 May – 3 June Let’s walk the talk! Aboriginal Sydney: A guide to important places of the past and present, 2nd Edition Melinda HINKSON and Alana HARRIS Sydney has a rich and complex Aboriginal heritage. Hidden within its burgeoning city landscape lie layers of a vibrant culture and a turbulent history. But, you need to know where to look. Aboriginal Sydney supplies the information. Aboriginal Sydney is both a guide book and an alternative social history told through an array of places of significance to the city’s Indigenous people. The sites, and their accompanying stories and photographs, evoke Sydney’s ancient past and celebrate the living Aboriginal culture of today. Back on The Block: Bill Simon’s Story Bill SIMON, Des MONTGOMERIE and Jo TUSCANO Stolen, beaten, deprived of his liberty and used as child labour, Bill Simon’s was not a normal childhood. He was told his mother didn’t want him, that he was ‘the scum of the earth’ and was locked up in the notorious Kinchela Boys Home for eight years. His experiences there would shape his life forever. Bill Simon got angry, something which poisoned his life for the next two decades. A life of self abuse and crime finally saw him imprisoned. But Bill Simon has turned his life around and in Back on the Block, he hopes to help others to do the same. These days Bill works on the other side of the bars, helping other members of the Stolen Generations find a voice and their place; finally putting their pain to rest. -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law. -

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy's Early Novels for Children

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy’s Early Novels for Children SUSAN SHERIDAN AND EMMA MAGUIRE Flinders University The 1950s marked an unprecedented development in Australian children’s literature, with the emergence of many new writers—mainly women, like Nan Chauncy, Joan Phipson, Patricia Wrightson, Eleanor Spence and Mavis Thorpe Clark, as well as Colin Thiele and Ivan Southall. Bush and rural settings were strong favourites in their novels, which often took the form of a generic mix of adventure story and the bildungsroman novel of individual development. The bush provided child characters with unique challenges, which would foster independence and strength of character. While some of these writers drew on the earlier pastoral tradition of the Billabong books,1 others characterised human relationships to the land in terms of nature conservation. In the early novels of Chauncy and Wrightson, the children’s relationship to the bush is one of attachment and respect for the environment and its plants and creatures. Indeed these novelists, in depicting human relationships to the land, employ something approaching the strong Indigenous sense of ‘country’: of belonging to, and responsibility for, a particular environment. Later, both Wrightson and Chauncy turned their attention to Aboriginal presence, and the meanings which Aboriginal culture—and the bloody history of colonial race relations— gives to the land. In their earliest novels, what is strikingly original is the way both writers use bush settings to raise questions about conservation of the natural environment, questions which were about to become highly political. In Australia, the nature conservation movement had begun in the late nineteenth century, and resulted in the establishment of the first national parks. -

Masculine Caregivers in Australian Children's Fictions 1953-2001

Chapter 3 Literary Reconfigurations of Masculinity I: Masculine caregivers in Australian children's fictions 1953-2001 'You're a failure as a parent, Joe Edwards!' Mavis Thorpe ClarkThe Min-Min (1966:185) It is easy to understand why men who grew up at a time when their fathers were automatically regarded as the head of the household and the breadwinner should feel rather threatened by the contemporary challenge to those central features of traditional masculine status ... Hugh Mackay Generations (1997:90) As cultural formations produced for young Australian readers, the children's fictions discussed in this chapter offer a diachronic study of literary processes employed to reconfigure schemas of adult masculinities.1 The pervasive interest in the transformation of Australian society's public gender order and its domestic gender regimes in the late twentieth century is reflected in children's fictions where reconfigurations of masculine subjectivities are represented with increasing narrative and discursive complexity. The interrogation of masculinity—specifically as fathering/caregiving—shifts in importance from a secondary level story in post-war realist fictions to the focus of the primary level story by the century's end. Thematically its significance changes too, from the reconfigurations of social relations in the domestic sphere that subverts the doxa of patriarchal legitimacy, to narratives that problematise masculinity in the public gender An earlier version of this chapter is published in Papers: Explorations into Children's Literature, 9: 1 (April 1999): 31-40. order. From the mid-1960s, feminist epistemologies provide the impetus for the first reconfiguration in the representations of fathering masculinities that challenges traditional patriarchy. -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

Blackfellas Music Credits

Composer David Milroy (cast) Woman with Accordian (sic) Hazel Winmar Credit Theme Orchestrated by Greg Schultz Music "Camp Theme" Performed by David Milroy Written by David Milroy "Waru" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Neil Murray, George Rurrambu (sic, also Rrurrambu) Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "Gotta Be Strong" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Neil Murray, George Rurrambu (sic) Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "My Island Home" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Neil Murray Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "In The Bush" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Sammy Butcher, Neil Murray, George Rurrambu (sic) Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "No Fear" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Neil Murray and Freddie Tallis Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "Breadline" Performed by Warumpi Band Written by Neil Murray Courtesy of Festival Records Published by Trafalgar Music "Dancing in the Moonlight" Performed by Coloured Stone Written by Buna Lawrie Courtesy of BMG/Coloured Stone "Lonely Life" Performed by Coloured sTone Written by Mackie Coaby Courtesy of BMG/Coloured Stone "When a Man Loves a Woman" Performed by Mark Bin Bakar Written by Mark Bin Bakar "Is the Man Guilty?" Performed by Mark Bin Bakar Written by Mark Bin Bakar "Our Love Will Never Die" Performed by Donna Atkins Written by Mark Bin Bakar "Last Kiss" Performed by Donna Atkins Written by Frank "Aching in My Body" Performed by Lorrae Coffin Written -

Disenchantment: a Novel for Young Adults with a Discussion of Representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in Books for Children and Young Adults

Disenchantment: a novel for young adults With a discussion of representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in books for children and young adults Rebecca Louise Hazleden BA (hons), (Leeds) MA, (Leeds Metropolitan University) PhD, (Exon) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of English, Media Studies and Art History 1 Abstract This thesis is in two parts. The first is the creative project, a love story called Disenchantment, which is a speculative fiction novel for young adults. The novel consists of the testimony of an imprisoned girl, indigenous to a fictitious island, explaining how she has ended up in a prison cell condemned to hang for a murder she did not commit. As she relates her story to a visitor, a tale emerges of love and betrayal set against a backdrop of colonialism and violence. At first, Neka is an awkward and fearful little child, suckled by a half-dead mother and weaned by a bitter old Healer. The adults remark what a pity it is that the bright light of her mother was snuffed out by such a dull child. But then she is chosen as assistant to Elu, the beautiful and vibrant rebel girl from another clan, who is to be the new Healer. They embark on their training together, drawing closer, learning the secrets of the clan, healing the sick, talking to the dead, encountering the god of lightning, and awakening the god of spring. Neka starts to find her place in the world, and her love blossoms – love for her land, her people, and most of all for Elu. -

Servant Class Behaviour at the Swan River in the Context of the British Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline@ND The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Arts Papers and Journal Articles School of Arts 2016 A culture for all: Servant class behaviour at the Swan river in the context of the British Empire S Burke University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/arts_article Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This article was originally published as: Burke, S. (2016). A culture for all: Servant class behaviour at the Swan river in the context of the British Empire. Studies in Western Australian History, 31, 25-39. Original article available here: http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=160614656471281;res=IELHSS This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/arts_article/123. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Culture for All: Servant class behaviour at the Swan River in the context of the British Empire Shane Burke* Tim Mazzarol’s 1978 paper ‘Tradition, Environment and the Indentured Labourer in early Western Australia’1 is one of the earliest specific works that attempted to identify the psyche of the first British colonists at Swan River and the ‘cultural baggage’—those fears, beliefs and backgrounds—they brought with them. About 80 per cent of the adult colonists to the Swan River were described by authorities as belonging to labouring and trade occupations.2 These might be called the servant or working classes, and are hereafter simply referred to in this paper as the servant class. -

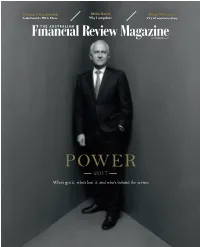

Who's Got It, Who's Lost It, and Who's Behind the Scenes

Trump v the swamp Mike Baird Ninja Warriors Leaks flood the White House Why I quit politics TV’s hit machine brothers OCTOBER 2017 POWER 2017 Who’s got it, who’s lost it, and who’s behind the scenes 8 LEAH PURCELL Actor, playwright, director Because: She allows white audiences to see from an Aboriginal perspective. Her radical adaptation of Henry Lawson’s The Drover’s Wife broke new ground for Australian theatre. Among its string of awards was the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for best drama, whose judges described it as “a declaration of war on Australia’s wilful historical amnesia”. Purcell, a Goa-Gunggari-Wakka Wakka Murri woman, uses the full arsenal of drama to tell new stories. In 2016 she co-directed Cleverman, which screened on ABC TV and meshed Aboriginal dreamtime stories into contemporary sci-fi genre. She also co-directed The Secret Daughter, which screened on Seven Network last year and has now been signed for a second series. Starring Jessica Mauboy, it marks the first time a commercial network has put an Indigenous Australian as the lead in a drama series. Season one was the second-highest rating drama for the year. What the panel says: She’s an Indigenous woman with a very political view. The Drover’s Wife was an incredible achievement and will make for a brilliant film. She also has two mainstream TV series on air and she’s winning every single award. – Graeme Mason The Drover’s Wife told the story in a completely different way to which it has been told before.