Eye Movements in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Rating Scale for Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration: a Pilot Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Clinical Rating Scale for Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration: A Pilot Study Alejandra Darling, MD,1 Cristina Tello, PhD,2 Marı´a Josep Martı´, MD, PhD,3 Cristina Garrido, MD,4 Sergio Aguilera-Albesa, MD, PhD,5 Miguel Tomas Vila, MD,6 Itziar Gaston, MD,7 Marcos Madruga, MD,8 Luis Gonzalez Gutierrez, MD,9 Julio Ramos Lizana, MD,10 Montserrat Pujol, MD,11 Tania Gavilan Iglesias, MD,12 Kylee Tustin,13 Jean Pierre Lin, MD, PhD,13 Giovanna Zorzi, MD, PhD,14 Nardo Nardocci, MD, PhD,14 Loreto Martorell, PhD,15 Gustavo Lorenzo Sanz, MD,16 Fuencisla Gutierrez, MD,17 Pedro J. Garcı´a, MD,18 Lidia Vela, MD,19 Carlos Hernandez Lahoz, MD,20 Juan Darı´o Ortigoza Escobar, MD,1 Laura Martı´ Sanchez, 1 Fradique Moreira, MD ,21 Miguel Coelho, MD,22 Leonor Correia Guedes,23 Ana Castro Caldas, MD,24 Joaquim Ferreira, MD,22,23 Paula Pires, MD,24 Cristina Costa, MD,25 Paulo Rego, MD,26 Marina Magalhaes,~ MD,27 Marı´a Stamelou, MD,28,29 Daniel Cuadras Palleja, MD,30 Carmen Rodrı´guez-Blazquez, PhD,31 Pablo Martı´nez-Martı´n, MD, PhD,31 Vincenzo Lupo, PhD,2 Leonidas Stefanis, MD,28 Roser Pons, MD,32 Carmen Espinos, PhD,2 Teresa Temudo, MD, PhD,4 and Belen Perez Duenas,~ MD, PhD1,33* 1Unit of Pediatric Movement Disorders, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain 2Unit of Genetics and Genomics of Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Disorders, Centro de Investigacion Prı´ncipe Felipe, Valencia, Spain 3Neurology Department, Hospital Clı´nic de Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomediques IDIBAPS. -

Management of Postpolio Syndrome

Review Management of postpolio syndrome Henrik Gonzalez, Tomas Olsson, Kristian Borg Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 634–42 Postpolio syndrome is characterised by the exacerbation of existing or new health problems, most often muscle weakness See Refl ection and Reaction and fatigability, general fatigue, and pain, after a period of stability subsequent to acute polio infection. Diagnosis is page 561 based on the presence of a lower motor neuron disorder that is supported by neurophysiological fi ndings, with exclusion Division of Rehabilitation of other disorders as causes of the new symptoms. The muscle-related eff ects of postpolio syndrome are possibly Medicine, Department of associated with an ongoing process of denervation and reinnervation, reaching a point at which denervation is no Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital (H Gonzalez MD, longer compensated for by reinnervation. The cause of this denervation is unknown, but an infl ammatory process is K Borg MD) and Department of possible. Rehabilitation in patients with postpolio syndrome should take a multiprofessional and multidisciplinary Clinical Neurosciences, Centre approach, with an emphasis on physiotherapy, including enhanced or individually modifi ed physical activity, and muscle for Molecular Medicine training. Patients with postpolio syndrome should be advised to avoid both inactivity and overuse of weak muscles. (T Olsson MD), Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden Evaluation of the need for orthoses and assistive devices is often required. Correspondence to: Henrik Gonzalez, Division of Introduction summary of the pathophysiology and clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, 12–20 million people worldwide have sequelae of characteristics of postpolio syndrome, outline diagnostic Department of Clinical Sciences, poliomyelitis, according to Post-Polio Health and treatment options, and suggest future research Karolinska Institute, Danderyd Hospital, S-182 88 Stockholm, International. -

Episodic Visual Snow Associated with Migraine Attacks

Letters RESEARCH LETTER Discussion | Three patients report episodes of VS exclusively at the beginning or during migraine attacks. The description was Episodic Visual Snow Associated identical and matched the definition of VS in VSS except for With Migraine Attacks not being continuous.1,2 In the syndrome-defining study,1 only Visual snow syndrome (VSS) is a debilitating disorder charac- patients with continuous VS were included, impeding the iden- terized by continuous visual snow (VS), ie, tiny flickering dots tification of an episodic form. Based on the present case se- in the entire visual field resembling the view of a badly tuned ries, we propose to distinguish between VSS, a debilitating dis- analog television (Figure), plus additional visual symptoms, order characterized by continuous VS and additional visual such as photophobia and palinopsia. There is a high comor- symptoms persisting over years, and eVS, an uncommon self- 1 bidity with migraine and migraine aura. To our knowledge, limiting symptom during migraine attacks. this is the first report of patients with an episodic form of VS The relationship between migraine and VSS is still (eVS), strictly co-occurring with migraine attacks. unresolved.3 Although the severity of VS in VSS does not fluc- tuate in parallel to the migraine cycle,1 the strict co-occurrence Methods | Between January 2016 and December 2017, we saw of eVS and migraine reported here epitomizes a close proxim- 3 patients with eVS and 1934 patients with migraine at our ter- ity.This is in agreement with the clinical picture of migraine being tiary outpatient headache center. -

Exacerbation of Motor Neuron Disease by Chronic Stimulation of Innate Immunity in a Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

1340 • The Journal of Neuroscience, February 11, 2004 • 24(6):1340–1349 Neurobiology of Disease Exacerbation of Motor Neuron Disease by Chronic Stimulation of Innate Immunity in a Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Minh Dang Nguyen,1 Thierry D’Aigle,2 Genevie`ve Gowing,1,2 Jean-Pierre Julien,1,2 and Serge Rivest2 1McGill University Health Center, Centre for Research in Neurosciences, McGill University, The Montreal General Hospital Research Institute, Montre´al, Que´bec H3G 1A4, Canada, and 2Laboratory of Molecular Endocrinology, Laval University Medical Center Research Center and Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Laval University, Sainte-Foy, Que´bec G1V 4G2, Canada Innate immunity is a specific and organized immunological program engaged by peripheral organs and the CNS to maintain homeostasis after stress and injury. In neurodegenerative disorders, its putative deregulation, featured by inflammation and activation of glial cells resulting from inherited mutations or viral/bacterial infections, likely contributes to neuronal death. However, it remains unclear to what extent environmental factors and innate immunity cooperate to modulate the interactions between the neuronal and non-neuronal elements in the perturbed CNS. In the present study, we addressed the effects of acute and chronic administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a Gram-negative bacterial wall component, in a genetic model of neurodegeneration. Transgenic mice expressing a mutant form of the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1 G37R) linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis were challenged intraperitoneally with a single nontoxic or repeated injections of LPS (1 mg/kg). At different ages, SOD1 G37R mice responded normally to acute endotoxemia. Remark- ably, only a chronic challenge with LPS in presymptomatic 6-month-old SOD1 G37R mice exacerbated disease progression by 3 weeks and motor axon degeneration. -

Treatment for Disease Modification in Chronic Neurodegeneration

cells Review Perspective: Treatment for Disease Modification in Chronic Neurodegeneration Thomas Müller 1,* , Bernhard Klaus Mueller 1 and Peter Riederer 2,3 1 Department of Neurology, St. Joseph Hospital Berlin-Weissensee, Gartenstr. 1, 13088 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 2 Center of Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Würzburg, Margarete-Höppel-Platz 1, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, Southern Denmark University Odense, J.B. Winslows Vey 18, 5000 Odense, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Symptomatic treatments are available for Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. An unmet need is cure or disease modification. This review discusses possible reasons for negative clinical study outcomes on disease modification following promising positive findings from experi- mental research. It scrutinizes current research paradigms for disease modification with antibodies against pathological protein enrichment, such as α-synuclein, amyloid or tau, based on post mortem findings. Instead a more uniform regenerative and reparative therapeutic approach for chronic neurodegenerative disease entities is proposed with stimulation of an endogenously existing repair system, which acts independent of specific disease mechanisms. The repulsive guidance molecule A pathway is involved in the regulation of peripheral and central neuronal restoration. Therapeutic antagonism of repulsive guidance molecule A reverses neurodegeneration according to experimental Citation: Müller, T.; Mueller, B.K.; outcomes in numerous disease models in rodents and monkeys. Antibodies against repulsive guid- Riederer, P. Perspective: Treatment for ance molecule A exist. First clinical studies in neurological conditions with an acute onset are under Disease Modification in Chronic Neurodegeneration. Cells 2021, 10, way. -

Gut–Brain Axis and Neurodegeneration: State-Of-The-Art of Meta-Omics Sciences for Microbiota Characterization

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Gut–Brain Axis and Neurodegeneration: State-of-the-Art of Meta-Omics Sciences for Microbiota Characterization Bruno Tilocca 1 , Luisa Pieroni 2 , Alessio Soggiu 3,4 , Domenico Britti 1 , Luigi Bonizzi 4, 1, , 5,6, Paola Roncada * y and Viviana Greco * 1 Department of Health Sciences, University “Magna Græcia” of Catanzaro, viale Europa, 88100 Catanzaro, Italy; [email protected] (B.T.); [email protected] (D.B.) 2 Proteomics and Metabonomics Unit, Fondazione Santa Lucia-IRCCS, via del Fosso di Fiorano, 64-00143 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences- One Health Unit, University of Milano, via Celoria 10, 20133 Milano, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Milano, Via dell’Università, 6- 26900 Lodi, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Basic Biotechnological Sciences, Intensivological and Perioperative Clinics, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Largo F. Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy 6 Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, Largo A. Gemelli, 8-00168 Rome, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.R.); [email protected] (V.G.) Which represents the co-corresponding author. y Received: 14 May 2020; Accepted: 4 June 2020; Published: 5 June 2020 Abstract: Recent advances in the field of meta-omics sciences and related bioinformatics tools have allowed a comprehensive investigation of human-associated microbiota and its contribution to achieving and maintaining the homeostatic balance. Bioactive compounds from the microbial community harboring the human gut are involved in a finely tuned network of interconnections with the host, orchestrating a wide variety of physiological processes. -

Capsaicin Prevents Degeneration of Dopamine Neurons by Inhibiting Glial Activation and Oxidative Stress in the MPTP Model of Parkinson’S Disease

OPEN Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2017) 49, e298; doi:10.1038/emm.2016.159 & 2017 KSBMB. All rights reserved 2092-6413/17 www.nature.com/emm ORIGINAL ARTICLE Capsaicin prevents degeneration of dopamine neurons by inhibiting glial activation and oxidative stress in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease Young C Chung1,8, Jeong Y Baek2,8, Sang R Kim3,4, Hyuk W Ko1, Eugene Bok4, Won-Ho Shin5, So-Yoon Won6 and Byung K Jin2,7 The effects of capsaicin (CAP), a transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 (TRPV1) agonist, were determined on nigrostriatal dopamine (DA) neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease (PD). The results showed that TRPV1 activation by CAP rescued nigrostriatal DA neurons, enhanced striatal DA functions and improved behavioral recovery in MPTP-treated mice. CAP neuroprotection was associated with reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β) and reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species from activated microglia-derived NADPH oxidase, inducible nitric oxide synthase or reactive astrocyte-derived myeloidperoxidase. These beneficial effects of CAP were reversed by treatment with the TRPV1 antagonists capsazepine and iodo-resiniferatoxin, indicating TRPV1 involvement. This study demonstrates that TRPV1 activation by CAP protects nigrostriatal DA neurons via inhibition of glial activation-mediated oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the MPTP mouse model of PD. These results suggest that CAP and its analogs may be beneficial therapeutic agents for the treatment of PD and other neurodegenerative disorders that are associated with neuroinflammation and glial activation-derived oxidative damage. -

Can Gut Microbe-Modifying Diet Prevent Or Alleviate the Symptoms of Neurodegenerative Diseases?

life Review Association of Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis with Neurodegeneration: Can Gut Microbe-Modifying Diet Prevent or Alleviate the Symptoms of Neurodegenerative Diseases? Li Yang Tan 1,2, Xin Yi Yeo 1,2 , Han-Gyu Bae 3 , Delia Pei Shan Lee 4 , Roger C. Ho 2,5 , Jung Eun Kim 4,* , Dong-Gyu Jo 3,* and Sangyong Jung 1,6,* 1 Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore 138667, Singapore; [email protected] (L.Y.T.); [email protected] (X.Y.Y.) 2 Department of Psychological Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119228, Singapore; [email protected] 3 School of Pharmacy, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Korea; [email protected] 4 Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117542, Singapore; [email protected] 5 Institute for Health Innovation & Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore 117599, Singapore 6 Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117593, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.E.K.); [email protected] (D.-G.J.); [email protected] (S.J.); Tel.: +65-64788744 (S.J.) Citation: Tan, L.Y.; Yeo, X.Y.; Bae, Abstract: The central nervous system was classically perceived as anatomically and functionally H.-G.; Lee, D.P.S.; Ho, R.C.; Kim, J.E.; independent from the other visceral organs. But in recent decades, compelling evidence has led the Jo, D.-G.; Jung, S. -

Monoclonal Antibodies As Neurological Therapeutics

pharmaceuticals Review Monoclonal Antibodies as Neurological Therapeutics Panagiotis Gklinos 1 , Miranta Papadopoulou 2, Vid Stanulovic 3, Dimos D. Mitsikostas 4 and Dimitrios Papadopoulos 5,6,* 1 Department of Neurology, KAT General Hospital of Attica, 14561 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 2 Center for Clinical, Experimental Surgery & Translational Research, Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens (BRFAA), 11527 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 3 Global Pharmacovigilance, R&D Sanofi, 91385 Chilly-Mazarin, France; vid.stanulovic@sanofi.com 4 1st Neurology Department, Aeginition Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 11521 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 5 Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Hellenic Pasteur Institute, 129 Vasilissis Sophias Avenue, 11521 Athens, Greece 6 Salpetriere Neuropsychiatric Clinic, 149 Papandreou Street, Metamorphosi, 14452 Athens, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Over the last 30 years the role of monoclonal antibodies in therapeutics has increased enormously, revolutionizing treatment in most medical specialties, including neurology. Monoclonal antibodies are key therapeutic agents for several neurological conditions with diverse pathophysio- logical mechanisms, including multiple sclerosis, migraines and neuromuscular disease. In addition, a great number of monoclonal antibodies against several targets are being investigated for many more neurological diseases, which reflects our advances in understanding the pathogenesis of these -

Recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder

Recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders Connie Marras 1 MD, PhD, Anthony Lang MD 1, Bart P. van de Warrenburg,4 Carolyn Sue, 3 Sarah J. Tabrizi MBChB, PhD, 5 Lars Bertram MD, 6,7 Katja Lohmann 2 PhD, Saadet Mercimek-Mahmutoglu, MD, PhD, 8 Alexandra Durr 9, Vladimir Kostic 10 , Christine Klein 2 MD, 1Toronto Western Hospital Morton and Gloria Shulman Movement Disorders Centre and the Edmond J. Safra Program in Parkinson’s disease, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 2Institute of Neurogenetics, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany 3Department of Neurology, Royal North Shore Hospital and Kolling Institute of Medical Research, University of Sydney, St Leonards, NSW 2065, Australia 4Department of Neurology, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behaviour, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 5Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Institute of Neurology, University College London, UK 6 Platform for Genome Analytics, Institute of Neurogenetics, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany 7School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College, London, UK 8Division of Clinical and Metabolic Genetics, Department of Pediatrics, University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada 9 Sorbonne Université, UPMC Univ Paris 06, UM 75, ICM, F-75013 Paris, France; Inserm, U 1127, ICM, F-75013 Paris, France; Cnrs, UMR 7225, ICM, F-75013 Paris, France; ICM, Paris, F-75013 Paris, France; AP-HP, Hôpital de -

Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection in Multiple Sclerosis and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases ⁎ Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut , Douglas L

Journal of Neuroimmunology 176 (2006) 198–215 www.elsevier.com/locate/jneuroim Conference report Neurodegeneration and neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative diseases ⁎ Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut , Douglas L. Arnold, Don W. Cleveland, Mark Fisher, Robert M. Friedlander, M. Maral Mouradian, Serge Przedborski, Bruce D. Trapp, Tony Wyss-Coray, V. Wee Yong UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ, United States McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada UCSD, San Diego, CA, United States University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA, United States Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States Columbia University, New York, NY, United States The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States Stanford University, Paolo Alto, CA, United States University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada Received 3 March 2006; accepted 6 March 2006 Abstract Multiple sclerosis is considered a disease of myelin destruction; Parkinson's disease (PD), one of dopaminergic neuron depletion; ALS, a disease of motor neuron death; and Alzheimer's, a disease of plaques and tangles. Although these disorders differ in important ways, they also have common pathogenic features, including inflammation, genetic mutations, inappropriate protein aggregates (e.g., Lewy bodies, amyloid plaques), and biochemical defects leading to apoptosis, such as oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. In most disorders, it remains uncertain whether inflammation and protein aggregation are neurotoxic or neuroprotective. Elucidating the mechanisms -

Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases

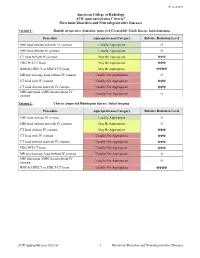

Revised 2019 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 1: Rapidly progressive dementia; suspected Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast Variant 2: Chorea; suspected Huntington disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 3: Parkinsonian syndromes. Initial