Approach to the Trauma Patient Will Help Reduce Errors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnoses to Include in the Problem List Whenever Applicable

Diagnoses to include in the problem list whenever applicable Tips: 1. Always say acute or open when applicable 2. Always relate to the original trauma 3. Always include acid-base abnormalities, AKI due to ATN, sodium/osmolality abnormalities 4. Address in the plan of your note 5. Do NOT say possible, potential, likely… Coders can only use a real diagnosis. Make a real diagnosis. Neurological/Psych: Head: 1. Skull fracture of vault – open vs closed 2. Basilar skull fracture 3. Facial fractures 4. Nerve injury____________ 5. LOC – include duration (max duration needed is >24 hrs) and whether they returned to neurological baseline 6. Concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 7. DAI/severe concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 8. Type of traumatic brain injury (hemorrhages and contusions) – include size a. Tiny = <0.6 cm b. Small/moderate = 0.6-1 cm c. Large/extensive = >1 cm 9. Cerebral contusion/hemorrhage 10. Cerebral edema 11. Brainstem compression 12. Anoxic brain injury 13. Seizures 14. Brain death Spine: 1. Cervical spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 2. Thoracic spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 3. Lumbar spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 4. Cord syndromes: central, anterior, or Brown-Sequard 5. Paraplegia or quadriplegia (any deficit in the upper extremity is consistent with quadriplegia) Cardiovascular: 1. Acute systolic heart failure 40 2. Acute diastolic heart failure 3. Chronic systolic heart failure 4. Chronic diastolic heart failure 5. Combined heart failure 6. Cardiac injury or vascular injuries 7. -

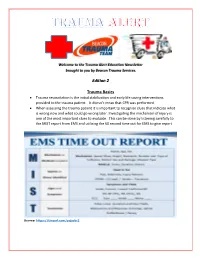

Edition 2 Trauma Basics

Welcome to the Trauma Alert Education Newsletter brought to you by Beacon Trauma Services. Edition 2 Trauma Basics Trauma resuscitation is the initial stabilization and early life saving interventions provided to the trauma patient. It doesn’t mean that CPR was performed. When assessing the trauma patient it is important to recognize clues that indicate what is wrong now and what could go wrong later. Investigating the mechanism of injury is one of the most important clues to evaluate. This can be done by listening carefully to the MIST report from EMS and utilizing the 60 second time out for EMS to give report Source: https://tinyurl.com/ycjssbr3 What is wrong with me? EMS MIST 43 year old male M= unrestrained driver, while texting drove off road at 40 mph into a tree, with impact to driver’s door, 20 minute extrication time I= Deformity to left femur, pain to left chest, skin pink and warm S= B/P- 110/72, HR- 128 normal sinus, RR- 28, Spo2- 94% GCS=14 (Eyes= 4 Verbal= 4 Motor= 6) T= rigid cervical collar, IV Normal Saline at controlled rate, splint left femur What are your concerns? (think about the mechanism and the EMS report), what would you prepare prior to the patient arriving? Ten minutes after arrival in the emergency department the patient starts to have shortness of breath with stridorous sound. He is now diaphoretic and pale. B/P- 80/40, HR- 140, RR- 36 labored. Absent breath sounds on the left. What is the patients’ underlying problem?- Answer later in the newsletter Excellence in Trauma Nursing Award Awarded in May for National Trauma Month This year the nominations were very close so we chose one overall winner and two honorable mentions. -

Boerhaave's Syndrome – Tension Hydropneumothorax and Rapidly

Boerhaave’s syndrome – tension hydropneumothorax and rapidly developing hydropneumothorax: two radiographic clues in one case Lam Nguyen Ho, Ngoc Tran Van & Thuong Vu Le Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Keywords Abstract Boerhaave’s syndrome, hydropneumothorax, methylene blue, pleural effusion, tension Boerhaave’s syndrome is a rare and severe condition with high mortality partly pneumothorax. because of its atypical presentation resulting in delayed diagnosis and management. Diagnostic clues play an important role in the approach to this syndrome. Here, we Correspondence report a 48 year-old male patient hospitalized with fever and left chest pain radiating Nguyen Ho Lam, Department of Internal into the interscapular area. Two chest radiographs undertaken 22 h apart showed a Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of rapidly developing tension hydropneumothorax. The amylase level in the pleural Medicine and Pharmacy, 217 Hong Bang fl fl Street, Ward 11, District 5, Ho Chi Minh City, uid was high. The uid in the chest tube turned bluish after the patient drank Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] methylene blue. The diagnosis of Boerhaave’s syndrome was suspected based on the aforementioned clinical clues and confirmed at the operation. The patient Received: 17 January 2016; Revised: recovered completely with the use of antibiotics and surgical treatment. In this case, 25 February 2016; Accepted: 10 March 2016 we describe key findings on chest radiographs that are useful in diagnosing Boerhaave’s syndrome. Respirology Case Reports, 4(4),2016,e00160 doi: 10.1002/rcr2.160 Introduction severe left chest pain radiating into the interscapular area. -

Managing a Rib Fracture: a Patient Guide

Managing a Rib Fracture A Patient Guide What is a rib fracture? How is a fractured rib diagnosed? A rib fracture is a break of any of the bones that form the Your doctor will ask questions about your injury and do a rib cage. There may be a single fracture of one or more ribs, physical exam. or a rib may be broken into several pieces. Rib fractures are The doctor may: usually quite painful as the ribs have to move to allow for normal breathing. • Push on your chest to find out where you are hurt. • Watch you breathe and listen to your lungs to make What is a flail chest? sure air is moving in and out normally. When three or more neighboring ribs are fractured in • Listen to your heart. two or more places, a “flail chest” results. This creates an • Check your head, neck, spine, and belly to make sure unstable section of chest wall that moves in the opposite there are no other injuries. direction to the rest of rib cage when you take a breath. • You may need to have an X-ray or other imaging test; For example, when you breathe in your rib cage rises out however, rib fractures do not always show up on X-rays. but the flail chest portion of the rib cage will actually fall in. So you may be treated as though you have a fractured This limits your ability to take effective deep breaths. rib even if an X-ray doesn’t show any broken bones. -

Trauma Treating Traumatic Facial Nerve Paralysis

LETTERS TO EDITOR 205 206 LETTERS TO EDITOR In conclusion, the most frequent type of HBV R. Hepatitis B virus genotype A is more often hearing loss, and an impedance audiogram Strands of facial nerve interconnect with genotype in our study was D type, which associated with severe liver disease in northern showed absent stapedial reflex. CT scan cranial nerves V, VIII, IX, X, XI, and XII and usually causes a mild liver disease. Hence India than is genotype D. Indian J Gastroenterol showed no fracture of the temporal bone and with the cervical cutaneous nerves. This free proper vaccination, e ducational programs, 2005;24:19-22. intact ossicles. The patient was prescribed intermingling of Þ bers of the facial nerve with and treatment with lamivudine are efficient 6. Thakur V, Sarin SK, Rehman S, Guptan RC, high-dose steroids, along with vigorous facial Þ bers of other neural structures (particularly Kazim SN, Kumar S. Role of HBV genotype strategies in controlling HBV infection in our nerve stimulation and massages. the cranial nerve V) has been proposed as in predicting response to lamivudine therapy area. the mechanism of spontaneous return of facial in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Indian J After 3 weeks of treatment, the facial nerve nerve function after peripheral injury to the Gastroenterol 2005;24:12-5. stimulation tests were repeated and the ABDOLVAHAB MORADI, nerve.[4] VAHIDEH KAZEMINEJHAD1, readings were compared to those taken prior to GHOLAMREZA ROSHANDEL, treatment. There was negligible improvement. KHODABERDI KALAVI, Early onset/complete palsy indicates disruption EZZAT-OLLAH GHAEMI2, SHAHRYAR SEMNANI The patient was offered an exploratory of continuity of the nerve. -

Cervical Spine Injury Risk Factors in Children with Blunt Trauma Julie C

Cervical Spine Injury Risk Factors in Children With Blunt Trauma Julie C. Leonard, MD, MPH,a Lorin R. Browne, DO,b Fahd A. Ahmad, MD, MSCI,c Hamilton Schwartz, MD, MEd,d Michael Wallendorf, PhD,e Jeffrey R. Leonard, MD,f E. Brooke Lerner, PhD,b Nathan Kuppermann, MD, MPHg BACKGROUND: Adult prediction rules for cervical spine injury (CSI) exist; however, pediatric rules abstract do not. Our objectives were to determine test accuracies of retrospectively identified CSI risk factors in a prospective pediatric cohort and compare them to a de novo risk model. METHODS: We conducted a 4-center, prospective observational study of children 0 to 17 years old who experienced blunt trauma and underwent emergency medical services scene response, trauma evaluation, and/or cervical imaging. Emergency department providers recorded CSI risk factors. CSIs were classified by reviewing imaging, consultations, and/or telephone follow-up. We calculated bivariable relative risks, multivariable odds ratios, and test characteristics for the retrospective risk model and a de novo model. RESULTS: Of 4091 enrolled children, 74 (1.8%) had CSIs. Fourteen factors had bivariable associations with CSIs: diving, axial load, clotheslining, loss of consciousness, neck pain, inability to move neck, altered mental status, signs of basilar skull fracture, torso injury, thoracic injury, intubation, respiratory distress, decreased oxygen saturation, and neurologic deficits. The retrospective model (high-risk motor vehicle crash, diving, predisposing condition, neck pain, decreased neck mobility (report or exam), altered mental status, neurologic deficits, or torso injury) was 90.5% (95% confidence interval: 83.9%–97.2%) sensitive and 45.6% (44.0%–47.1%) specific for CSIs. -

Chest and Abdominal Radiograph 101

Chest and Abdominal Radiograph 101 Ketsia Pierre MD, MSCI July 16, 2010 Objectives • Chest radiograph – Approach to interpreting chest films – Lines/tubes – Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum/pneumopericar dium – Pleural effusion – Pulmonary edema • Abdominal radiograph – Tubes – Bowel gas pattern • Ileus • Bowel obstruction – Pneumoperitoneum First things first • Turn off stray lights, optimize room lighting • Patient Data – Correct patient – Patient history – Look at old films • Routine Technique: AP/PA, exposure, rotation, supine or erect Approach to Reading a Chest Film • Identify tubes and lines • Airway: trachea midline or deviated, caliber change, bronchial cut off • Cardiac silhouette: Normal/enlarged • Mediastinum • Lungs: volumes, abnormal opacity or lucency • Pulmonary vessels • Hila: masses, lymphadenopathy • Pleura: effusion, thickening, calcification • Bones/soft tissues (four corners) Anatomy of a PA Chest Film TUBES Endotracheal Tubes Ideal location for ETT Is 5 +/‐ 2 cm from carina ‐Normal ETT excursion with flexion and extension of neck 2 cm. ETT at carina Right mainstem Intubation ‐Right mainstem intubation with left basilar atelectasis. ETT too high Other tubes to consider DHT down right mainstem DHT down left mainstem NGT with tip at GE junction CENTRAL LINES Central Venous Line Ideal location for tip of central venous line is within superior vena cava. ‐ Risk of thrombosis decreased in central veins. ‐ Catheter position within atrium increases risk of perforation Acceptable central line positions • Zone A –distal SVC/superior atriocaval junction. • Zone B – proximal SVC • Zone C –left brachiocephalic vein. Right subclavian central venous catheter directed cephalad into IJ Where is this tip? Hemiazygous Or this one? Right vertebral artery Pulmonary Arterial Catheter Ideal location for tip of PA catheter within mediastinal shadow. -

Chapter 42 – Facial Trauma

CrackCast Show Notes – Facial Trauma– September 2016 www.canadiem.org/crackcast Chapter 42 – Facial Trauma Episode Overview: 1) Describe the anatomy of the bones, glands, and ducts of the face. At what ages do the sinuses appear? 2) List 5 types of facial fractures. 3) Describe the clinical presentation and associated radiographic findings of an orbital blowout fracture. 4) Describe an orbital tripod fracture and its management. 5) List the indications for antibiotics in a patient with facial trauma? 6) What is the importance of perioral electrical burns? 7) What are the indications for specialist repair of an eyelid laceration? 8) Describe the classification and management of dental fractures. a. What is the management of an avulsed tooth? b. What is a luxed tooth? How is it managed? c. What is an alveolar ridge fracture? 9) Describe the method for reducing a jaw dislocation? What is the usual direction of the dislocation? Rosen’s in Perspective mechanism of facial trauma varies significantly age highly associated with alcohol use o 49% of maxillofacial trauma was ETOH related in one study . Of these, 78% were related to violence and assaults, and 13% to motor vehicle collisions. other common mechanisms include falls, animal bites, sports, and flying debris. much more common in unprotected vehicle users such as ATVs and motorcycles o 32% of injured ATV riders will have facial injuries. facial injury in these patients correlates with injury severity score children < 17 years old, sports injuries are the largest source of facial injuries (20%) children < 6 years old most commonly suffer facial injuries from family pets such as dogs in young children the face is the most common location of trauma associated with abuse. -

Pneumothorax Ex Vacuo in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion After Pleurx Catheter Placement

The Medicine Forum Volume 16 Article 20 2015 Pneumothorax ex vacuo in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion After PleurX Catheter Placement Meera Bhardwaj, MS4 Thomas Jefferson University, [email protected] Loheetha Ragupathi, MD Thomas Jefferson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/tmf Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Bhardwaj, MS4, Meera and Ragupathi, MD, Loheetha (2015) "Pneumothorax ex vacuo in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion After PleurX Catheter Placement," The Medicine Forum: Vol. 16 , Article 20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29046/TMF.016.1.019 Available at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/tmf/vol16/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Medicine Forum by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Bhardwaj, MS4 and Ragupathi, MD: Pneumothorax ex vacuo in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion After PleurX Catheter Placement Pneumothorax ex vacuo in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion After PleurX Catheter Placement Meera Bhardwaj, MS4 and Loheetha Ragupathi, MD INTRODUCTION Pneumothorax ex vacuo (“without vaccuum”) is a type of pneumothorax that can develop in patients with large pleural effusions. -

Anesthesia for Trauma

Anesthesia for Trauma Maribeth Massie, CRNA, MS Staff Nurse Anesthetist, The Johns Hopkins Hospital Assistant Professor/Assistant Program Director Columbia University School of Nursing Program in Nurse Anesthesia OVERVIEW • “It’s not the speed which kills, it’s the sudden stop” Epidemiology of Trauma • ~8% worldwide death rate • Leading cause of death in Americans from 1- 45 years of age • MVC’s leading cause of death • Blunt > penetrating • Often drug abusers, acutely intoxicated, HIV and Hepatitis carriers Epidemiology of Trauma • “Golden Hour” – First hour after injury – 50% of patients die within the first seconds to minutesÆ extent of injuries – 30% of patients die in next few hoursÆ major hemorrhage – Rest may die in weeks Æ sepsis, MOSF Pre-hospital Care • ABC’S – Initial assessment and BLS in trauma – GO TEAM: role of CRNA’s at Maryland Shock Trauma Center • Resuscitation • Reduction of fractures • Extrication of trapped victims • Amputation • Uncooperative patients Initial Management Plan • Airway maintenance with cervical spine protection • Breathing: ventilation and oxygenation • Circulation with hemorrhage control • Disability • Exposure Initial Assessment • Primary Survey: – AIRWAY • ALWAYS ASSUME A CERVICAL SPINE INJURY EXISTS UNTIL PROVEN OTHERWISE • Provide MANUAL IN-LINE NECK STABILIZATION • Jaw-thrust maneuver Initial Assessment • Airway cont’d: – Cervical spine evaluation • Cross table lateral and swimmer’s view Xray • Need to see all seven cervical vertebrae • Only negative CT scan R/O injury Initial Assessment • Cervical -

Middle Ear Disorders

3/2/2014 ENT CARRLENE DONALD, MMS PA-C ANTHONY MENDEZ, MMS PA-C MAYO CLINIC ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY AND HEAD & NECK SURGERY No Disclosures OBJECTIVES • 1. Identify important anatomic structures of the ears, nose, and throat • 2. Assess and treat disorders of the external, middle and inner ear • 3. Assess and treat disorders of the nose and paranasal sinuses • 4. Assess and treat disorders of the oropharynx and larynx • 5. Educate patients on the risk factors for head and neck cancers 1 3/2/2014 Otology External Ear Disorders External Ear Anatomy 2 3/2/2014 Trauma • Variety of presentations. • Rule out temporal bone trauma (battle’s sign & hemotympanum). CT head w/out contrast. • Tx lacerations/avulsions with copious irrigation, closure with dissolvable sutures (monocryl), tetanus update, and antibiotic coverage (anti- Pseudomonal). May need to bolster if concerned for a hematoma . Auricular Hematoma • Due to blunt force trauma. • Drain/aspirate, cover with anti- biotics (anti- Pseudomonals), and apply bolster or passive drain if needed. • Infection and/or cauliflower ear may result if not treated. Chondritis • Inflammation and infection of the auricular cartilage. usually due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. • Cultures • Treat with empiric antibiotics (anti-Pseudomonal) and I&D if needed. • Differentiate from relapsing polychondritis, which is an autoimmune disorder. 3 3/2/2014 External Auditory Canal Foreign Body • Children –Foreign bodies • Adults – Cerumen plugs • May present with hearing loss, ear pain and drainage • Exam under microscopic otoscopy. Check for otitis externa. • Remove under direct visualization. Can try to neutralize bugs with mineral oil. Do not attempt to irrigate organic material with water as this may cause an infection. -

Crush Injuries Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Michael Sahjian, RN, BSN, CFRN, CCRN, NREMT-P; Michael Frakes, APRN, CCNS, CCRN, CFRN, NREMT-P

LWW/AENJ LWWJ331-02 April 23, 2007 13:50 Char Count= 0 Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 145–150 Copyright c 2007 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Crush Injuries Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Michael Sahjian, RN, BSN, CFRN, CCRN, NREMT-P; Michael Frakes, APRN, CCNS, CCRN, CFRN, NREMT-P Abstract Crush syndrome, or traumatic rhabdomyolysis, is an uncommon traumatic injury that can lead to mismanagement or delayed treatment. Although rhabdomyolysis can result from many causes, this article reviews the risk factors, symptoms, and best practice treatments to optimize patient outcomes, as they relate to crush injuries. Key words: crush syndrome, traumatic rhabdomyolysis RUSH SYNDROME, also known as ology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and early traumatic rhabdomyolysis, was first re- management of crush syndrome. Cported in 1910 by German authors who described symptoms including muscle EPIDEMIOLOGY pain, weakness, and brown-colored urine in soldiers rescued after being buried in struc- Crush injuries may result in permanent dis- tural debris (Gonzalez, 2005). Crush syn- ability or death; therefore, early recognition drome was not well defined until the 1940s and aggressive treatment are necessary to when nephrologists Bywaters and Beal pro- improve outcomes. There are many known vided descriptions of victims trapped by mechanisms inducing rhabdomyolysis includ- their extremities during the London Blitz ing crush injuries, electrocution, burns, com- who presented with shock, swollen extrem- partment syndrome, and any other pathology ities, tea-colored urine, and subsequent re- that results in muscle damage. Victims of nat- nal failure (Better & Stein, 1990; Fernan- ural disasters, including earthquakes, are re- dez, Hung, Bruno, Galea, & Chiang, 2005; ported as having up to a 20% incidence of Gonzalez, 2005; Malinoski, Slater, & Mullins, crush injuries, as do 40% of those surviving to 2004).