From Blueprint to Scale: the Case for Philanthropy in Impact Investing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ONFI-2017-990-PF.Pdf

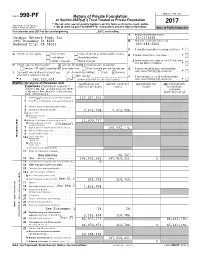

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2017 G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , A Employer identification number Omidyar Network Fund, Inc 20-1173866 1991 Broadway St #200 B Telephone number (see instructions) Redwood City, CA 94063 650-482-2500 C If exemption application is pending, check here. G G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D1Foreign organizations, check here. G Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation . G H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here. G IJFair market value of all assets at end of year Accounting method: CashX Accrual (from Part II, column (c), line 16) Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination G $ 545,202,008. (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here. G Part I Analysis of Revenue and (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitable columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes sarily equal the amounts in column (a) (cash basis only) (see instructions).) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received (attach schedule). -

FROM LOCAL to GLOBAL in 2010, After a Decade Focused on Its Home City of Boston, the Barr Foundation Launched a Pilot in Global Grantmaking

FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL In 2010, after a decade focused on its home city of Boston, the Barr Foundation launched a pilot in global grantmaking. Over the next three years, guided by a vision for a vibrant, just, and sustainable world with hopeful futures for children, the foundation engaged with over 20 organizations striving to improve the lives of children and families living in poverty in East Africa, India, and Haiti. This booklet summarizes our approach, grant investments, and learning from this initiative. Contents 04 A Message from Barbara Hostetter Chair of Barr Foundation’s Board of Trustees 05 Reflections from Heiner Baumann Director of Barr Foundation’s Global Programs 06 Four Interconnected Portfolios 08 Three Priority Geographies 10 Grantee Profiles in… Community Health 10 Sustainable Agriculture 22 Clean Energy 42 Exploration And Learning 52 64 Looking Back, Looking Forward 68 Portfolio Logic Models 70 Barr Global Staff 70 Acknowledgments 71 Grantee Websites BARR FOUNDATION FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL 3 From local to global I am pleased to introduce this booklet, which shares the Barr Foundation’s early work and learning from a three-year pilot in global giving. In 2010, after a decade focused on our home city of Boston, we set out to learn whether a small Boston- based team could find meaningful ways to engage with efforts to improve the lives of children and families in the Global South. We began with many questions. Over three years, we have answered some of them. Yet in this work we have found there are always questions beyond questions. The one thing we know for certain is that our learning has only begun. -

Scaling Pathways- Financing for Scaled Impact

Scaling Catherine Clark, Kimberly Langsam, Ellen Martin, and Erin Worsham Pathways MARCH 2018 Insights from the field on unlocking impact at scale FINANCING FOR SCALED IMPACT Innovation Investment Alliance, Skoll Foundation, and CASE at Duke ABOUT THE SCALING PATHWAYS SERIES Googling “social enterprise” calls up over 20 million links. Indeed, there are hundreds of thousands of new ideas for mission-driven ventures emerging around the world. And there are some notable social enterprise organizations who have started to solve social and environmental problems at scale. What can we learn from the experiences of these organizations? Their hard-won lessons can benefit other social enterprises, funders, and the surrounding ecosystem. Social enterprises often work on problems that are deeply entrenched, depend on cross-sector collaboration, and require multiple pathways to scale their impact and create systems-level change. The road to scaled impact is a nonlinear, complicated journey. Along the way, the organizations have to overcome many challenges and roadblocks, including the following: Financing for Scale: Determining Government Partnerships: which financing strategies best support Effectively cultivating and managing their plan for impact at scale. partnerships with government and other actors in order to increase impact. Pathways to Scale: Data: Understanding Assessing which of the many how to best use data to pathways to scale will most drive performance, impact efficiently and effectively drive management, and decision- towards their desired end game making as they scale. Talent: Defining the different talent strategies needed to identify, train, and retain the human capital needed for scale. The Scaling Pathways Theme Studies series dives into each of these topics in-depth, bringing to light lessons learned by successful social enterprises who have navigated these challenges on the road to scaled impact. -

Technology and Entrepreneurship 12 57 71 Making Every Big Data: the New Face Nutrition

Details on the ELEVATOR PITCH CONTEST ⇢ page 07 TECHNOLOGY AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP 12 57 71 MAKING EVERY BIG DATA: THE NEW FACE NUTRITION MOVE COUNT FOR HUMANITARIAN AID ENTREPRENEURS Contents 05 Editorial Special Feature 08 Infograph Innovative Technologies from Farm to Fork 84 New Horizons for the Forgotten Generation Food for Thought 91 Multisectoral Tools to Guide National and District Anemia Programming 10 Big Data: A Gift to the Nutrition Community? 97 The Belly of Paris: Hunger in the face of plenty 12 Making Every Move Count The Bigger Picture Research-Based Evidence 102 A Day in the Life of Rajan Sankar 20 Carotenoids and Breast Cancer Congress Reports 27 The Sociocultural Drivers of Food Choices 106 The 18th International Symposium on Carotenoids Perspectives in Nutrition Science Field Reports 36 New Allies Accelerate the Fight against Malnutrition 112 The Power of Portable Micronutrient Testing 42 Omics Innovations and Applications for Public Health Nutrition 118 Knowledge Can Empower 53 Insect Rearing for Processing Protein in Animal Feed 123 Leveraging Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship for Targeting Malnutrition 57 Big Data: The New Face of Humanitarian Aid 128 Eggciting Innovations 61 Technology-Enabled Incentives for Last-Mile Entrepreneurs 133 Six Important Characteristics of a Successful Microfranchisee 65 Using Mobile Technology for Nutrition Programs 144 What’s new 71 Nutrition Entrepreneurs 164 Reviews & Notices 78 Personalized Nutrition 166 Imprint ⇢ 04 EDITORIAL “ Telemedicine, predictive diagnostics, wearable sensors and a host of new mobile applications are transforming how people manage their health” 05 Welcome Technology: a tectonic movement in all forms in even the remotest areas of the world. -

Living Goods: Sustainability and Impact of Hybrid Models in the Developing World

Living Goods: Sustainability and Impact of Hybrid Models in the Developing World The Need for a Scalable Game-Changing Health Solution Dissertation by Filipa Páscoa Student Number: 152114304 Academic Advisor Professor Susana Frazão Pinheiro Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Degree of MSc in Management, Major in Strategy and Consulting at Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics June 2016 ABSTRACT Thesis title: Living Goods: Sustainability and Impact of Hybrid Models in Health Systems in the Developing World Sub-title: The need for a scalable game-changing health solution Author: Filipa Páscoa The aim of this dissertation is to study how an innovative system, the hybrid model, has the potential to solve the severe health issues that are present in today’s developing world. The problem statement is based on understanding how can this type of model be sustainable and how great of an impact it can achieve; while also realizing if it presents itself as a scalable solution. In order to do so, a teaching case was developed, based on LG, an American based social enterprise that created a personalized hybrid model to tackle the health issues in the developing world, with the ultimate goal of improving health status of entire populations. A pioneer user of this model in the healthcare industry, LG is now a fully established organization, operating in Uganda, Kenya, Myanmar and Zambia and having improved the lives of millions. In the following pages the dissertation’s entire outline is introduced and there is a methodology section to explain how the data was collected. -

Jorm 990-PF 2013 40

OMB No 1545-0052 jorm 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(aXl) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its sepa rate instruction s is at www.irs.go v/form 990pf. Employer identification number Omidyar Network Fund, Inc 20-1173866 1991 Broadway Street #200 6 Telephone number (see the instructions) Redwood City, CA 94063 Il 650-482-2500 V II Cseiiipuull dptl111Auu11 1J JiiUII ny, 1.111U.1% IICIC - I I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Li Final return Amended return D 1 Foreign organizations, check here ll^ 11 Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check H Check type of organization R Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation here and attach computation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation 11 E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash X Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) [) Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here $ 319 941 051. (Part column (d) must be on cash bas(s - Part Ana lysis O R evenue an d (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitab le columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes (cash sarily equal the amounts in column (a) basis only) n (see instructions) ) •;3 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc , received (aft sch) 78 , 654 , 020. -

Investing in Inclusive Business in Asia: a Regional Forum

1 26 Nov 2012 ASIA INCLUSIVE BUSINESS FORUM 28-29 November 2012, Manila, ADB Office Resource Speakers James ADDO is the Senior Manager of SNV‟s Impact Investment Advisory Services practice. He manages the development and execution of global impact investment strategy across SNV‟s 36 countries and 4 continents. James is an experienced investment banker with a specialty in private equity and venture capital opportunities. He is a well-rounded Investment Banking Professional with broad experience in conventional and impact investments. James has multi-year experience in establishing and managing development finance programs in 6 sub Saharan African countries. He brings to SNV‟s impact investment advisory practice, the rigor of the private equity and venture capital investment process to together with an understanding of multi-sector development venture finance. He served until April 30 2010 as Group Chief Executive Officer of Securities Africa Limited, a full service Pan-African investment bank with offices in UK, US, Malta, Bermuda and 7 countries in Africa‟s main markets. He covered all 53 countries and 25 capital markets. Prior to that he was a Portfolio Manager of Finch Africa Fund, a $50MM Africa focused equity fund. James, in the previous 8 years, worked in development venture investments with the US Government. He was a Senior Investment Banker from 1992 through 2001 with major firms, including Merrill Lynch. James received his BA from Dartmouth College and completed his MBA from Frank Zarb School of Business (Hofstra University) and Stern University both in New York in 1992. Anurag AGRAWAL is a Co-Founder, Board member and Chief Operating Officer at Intellecap, a firm founded in 2002 which provides innovative business solutions that help build and scale profitable and sustainable enterprises dedicated to social and environmental change. -

From Start-Up to Scale Conversations from the Harvard Business Review- Bridgespan Insight Center on Scaling Social Impact

Created with support from From Start-up to Scale Conversations from the Harvard Business Review- Bridgespan Insight Center on Scaling Social Impact Collaborating to accelerate social impact May 2013 Table of Contents Introduction ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Scaling Social Impact: What to Do and How to Fund it �������������������������������������������������� 5 Should Your Business Be Nonprofit or For‑Profit? ������������������������������������������������������� 7 When You Should Seek Capital from an Impact Investor ���������������������������������������� 10 Social Impact Investing Will Be the New Venture Capital ����������������������������������������13 Venture Capital with a Twist: How to Pitch an Impact Investor �����������������������������16 It’s Not All About Growth for Social Enterprises ����������������������������������������������������������19 The Talent Needed for Social Impact ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 To Change the World, Fear Means Go �����������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Entrepreneurs: You’re More Important Than Your Business Plan �������������������������28 Build Your Bench Strength Without Breaking the Bank �������������������������������������������31 Want to Change the World? Be Resilient� ����������������������������������������������������������������������34 Lessons from a Failed Social Entrepreneur �������������������������������������������������������������������37 -

Africa Program Handout

INVESTING IN AFRICA Philanthropy & Beyond Hosted by October 30 // 10:30a-6:00p Google Community Space // SF [SURVEY URL] Agenda 10:00-10:30 Registration 10:30-11:15 Stop the Pity: The Art of Ethical Storytelling // Katrina Boratko, Katie Carey- Nivard, Mama Hope 11:15-12:00 Girl Rising: Storytelling for Social Change // Martha Adams, Girl Rising / David Wood, Equal Access 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-1:15 Welcome Remarks // Rahul Young, Tides / Ken Inadomi, Project Redwood 1:15-2:00 Dispelling the Myths of Investing in Africa // John Earhart, Global Environment Fund / Niamani Mutima, Africa Grantmakers' Affinity Group 2:00-2:45 Partnering with Grantees to Build Capacity // Ken Inadomi, Project Redwood / Chesca Colloredo-Mansfeld, MiracleFeet / Kevin Starr, Mulago Foundation 2:45-3:00 Table Host Introductions 3:00-3:15 Break 3:15-4:00 Table Topics / Sarah Koch, Development in Gardening / Ayesha Wagle, Komaza / Anina Tweed & Annie Winkler, Living Goods / Katrina Boratko & Katie Carey, Mama Hope / Liezl Van Riper & Jane Ullman, myAgro / Mark Gonzales, The New Medina / Matt Bauer, Sparrow 4:00-4:30 Keynote // Chid Liberty, Liberty & Justice 4:30-5:00 Closing Reflection // Harris Bostic, Tides / Ayesha Wagle, Komaza / Chivy Sok, Tikva Grassroots Empowerment Fund 5:00-6:30 Reception Table Topics Using Empathy and Deep Listening in the Field as Development Tools // Development in Gardening Host: Sarah Koch, Executive Director & Founder Operations In: Burkina Faso, Kenya, Namibia, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia Development in Gardening (DIG) is designing agricultural solutions for nutritionally vulnerable families that are economically feasible, culturally appropriate and environmentally restorative. -

Financial Sustainability in Social Franchising: Promising Approaches

Financial sustainability in social franchising: Promising approaches and emerging questions Financial sustainability in social franchising: Promising approaches and emerging questions Copyright © 2014 UCSF Global Health Group The Global Health Group Global Health Sciences University of California, San Francisco 550 16th Street, 3rd Floor San Francisco, CA 94158 USA Email: [email protected] Website: globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/global-health-group Ordering information This publication is available for electronic download at sf4health.org/research-evidence/reports-and-case-studies. Recommended citation Beyeler, N., Briegleb, C., Sieverding, M. (2014). Financial sustainability in social franchising: promising approaches and emerging questions. San Francisco: Global Health Group, Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco. All photos courtesy of the social franchising programs, except for the BlueStar photo on the cover and the photos on pages 10, 15, and 35, which are by Karen Schlein. Produced in the United States of America. First Edition, December 2014 This is an open-access document distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited. Contents Executive summary | 1 Introduction | 3 Methods | 3 Background | 3 Defining sustainability | 4 Social franchise approaches to sustainability | 5 Strategy #1: Build franchisee business capacity and -

From Start-Up to Scale (Pdf)

Created with support from From Start-up to Scale Conversations from the Harvard Business Review- Bridgespan Insight Center on Scaling Social Impact Collaborating to accelerate social impact May 2013 Table of Contents Introduction ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Scaling Social Impact: What to Do and How to Fund it �������������������������������������������������� 5 Should Your Business Be Nonprofit or For‑Profit? ������������������������������������������������������� 7 When You Should Seek Capital from an Impact Investor ���������������������������������������� 10 Social Impact Investing Will Be the New Venture Capital ����������������������������������������13 Venture Capital with a Twist: How to Pitch an Impact Investor �����������������������������16 It’s Not All About Growth for Social Enterprises ����������������������������������������������������������19 The Talent Needed for Social Impact ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 To Change the World, Fear Means Go �����������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Entrepreneurs: You’re More Important Than Your Business Plan �������������������������28 Build Your Bench Strength Without Breaking the Bank �������������������������������������������31 Want to Change the World? Be Resilient� ����������������������������������������������������������������������34 Lessons from a Failed Social Entrepreneur �������������������������������������������������������������������37 -

We Are Working to Solve One of Africa's Toughest Problems

We are working to solve one of Africa’s toughest problems. THE BOMA PROJECT works with women who live in extreme poverty in the arid and semi-arid lands of Africa (the ASALs). In one of the poor- est places on the planet—the true “last mile” of economic and social isolation— we are empowering women, working to build resilient families and communities, BOMA operates at the nexus of four critical instilling hope, and changing the conversation about what is possible. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals—a global campaign to transform our world by 2030. No Poverty. Zero Hunger. Gender Equality. Climate Action. THE PROBLEM 700 million $1.90 50% OF EXTREME people globally live upper limit of live in sub- POVERTY in extreme poverty their daily income Saharan Africa The Proven Solution: Extreme poverty has multiple, inter-related causes. BOMA’s innovative program for ultra-poor women is based on a proven model* and takes a holistic approach to achieve long-lasting resiliency and forge a pathway to prosperity for millions of vulnerable people. HUMANITARIAN AID VS. MICROFINANCE VS. HOLISTIC APPROACH > Can save lives in a crisis but > Imposes debt and entails > Long-lasting systemic change creates a cycle of dependence navigating challenging financial > Cost-effective systems > Expensive > Transforms participants from > Challenging delivery systems > Not shown to have lasting liabilities into assets effect on poverty level *(“A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries;” Authors: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Nathanael Goldberg, Dean Karlan, Robert Osei, William Parienté, Jeremy Shapiro, Bram Thuysbaert, Christopher Udry; Science 15 May 2015: Vol.