Truth in Memoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Kit Festival of Small Halls Summer Tour 2019

MEDIA KIT FESTIVAL OF SMALL HALLS SUMMER TOUR 2019 Event Festival of Small Halls Presenting Line Woodfordia Inc in partnership with Cygnet Folk Festival, Illawarra Folk Festival and Woodford Folk Festival presents Festival of Small Halls Summer Tour 2019 featuring Fru Skagerrak and Liam Gerner Tour Partners Cygnet Folk Festival, Illawarra Folk Festival and Woodford Folk Festival Artists Fru Skagerrak (DEN/NOR/SWE) Liam Gerner (AUS) Regional Partners See Locations Tour Announce Date 8 November 2018 Tickets On Sale 8 November 2018 www.festivalofsmallhalls.com Prices vary by location Web www.festivalofsmallhalls.com Twitter site: https://twitter.com/SmallHallsAUS Handle: @SmallHallsAus #HallsSummer Instagram https://www.instagram.com/smallhallsaus/ MEDIA KIT FESTIVAL OF SMALL HALLS SUMMER TOUR 2019 YouTube http://www.youtube.com/user/festivalofsmallhalls Facebook https://www.facebook.com/festivalofsmallhalls Attachments/Provisions ● Artist biographies ● About Festival of Small Halls ● Locations, local partners ● Media release #1 + Simple Promo Paragraph ● Logo (1) ● Artist Images (3) PUBLICITY CONTACT: Sophia Broese van Groenou, Publicist [email protected] +61 413 897 880 Artist Biographies 3 Fru Skagerrak (DEN/NOR/SWE) 3 Liam Gerner (AUS) 5 Tour Location Details 7 General Promo 8 FROM PREVIOUS ARTISTS 9 FROM OUR PATRONS 11 IN THE MEDIA 11 MEDIA KIT FESTIVAL OF SMALL HALLS SUMMER TOUR 2019 Artist Biographies Fru Skagerrak (DEN/NOR/SWE) Short Biography Fru Skagerrak takes you on a journey through Scandinavia; from lowlands to mountains, from slow airs to roaring polkas, and everything in between. Three master musicians from each of the Scandinavian countries - the result is an explosion of the sounds that exist in Scandinavian traditional music today. -

The Lived Experience of Military Brats of Color In

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HOME: THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF MILITARY BRATS OF COLOR IN COLLEGE Alicia Marie Peralta, Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Dissertation directed by: Professor Francine H. Hultgren Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership Military children of color live in various cultural contexts, often outside of mainstream U.S. society, leading to questions about their experiences as young people of color in college settings. To this end, this dissertation asks: What is the lived experience of military brats of color in college? This dissertation explores the experiences of seven military children of color in college settings as they navigate leaving their unique military context, encounter identities they did not know they had, and individuate from their families and the military context. The phenomenological questioning of identity coupled with conceptions of home and belonging shine a light on the bittersweet experience of the military brats of color feeling like strangers in their own country. These experiences are uncovered using Gadamerian (1975/2004) horizons and Heidegger’s dasein (1927/2008b) in addition to O’Donohue’s (1997, 1998) philosophical writings on belonging and home. The thematizing process brought forth experiences of attempting to forge an identity in the midst of preconceived ideas about who and what you should be as a person. The process of forging identity includes the transition from the military community to college; a settling into college; and a choosing of identity. Pedagogical insights include a critique of identity and how it is constructed, specifically because military children of color are never of a place, but move with and in spaces. -

Annotated Edition

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of THE PICTURE A TRUE HUNGARIAN HISTORY by Philip Massinger Performed 1629 First Published 1630 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2019. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. 1 THE PICTURE A True Hungarian History By Philip Massinger Performed 1629 First Published 1630 A Tragecomedie, As it was often presented with good allowance, at the Globe, and Blacke Friers Play-houses, by the Kings Maiesties Servants. DRAMATIS PERSONAE. INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY The Hungarian Court: The Picture, by Philip Massinger, is a highly entertaining drama-comedy which explores what happens to people who Ladislaus, king of Hungary. are unable or unwilling to control their feelings and Honoria, the queen. affections: unchecked suspicion, embarrassingly Acanthe, maid of honour. unrestrained adoration, and even immoderate lust, all will Sylvia, maid of honour. be repaid. The Picture is likely the only Elizabethan play Ferdinand, general of the army. to take place in Hungary's ancient royal capital, Alba Eubulus, an old counsellor. Regalis, modern Székesfehérvár. Ubaldo, a wild courtier. Ricardo, a wild courtier. NOTES ON THE TEXT Bohemian Characters: The text of The Picture is adopted from Gifford's edition of our play, cited at #16 below, but with some Mathias, a knight of Bohemia. of the 1630 quarto's original spellings restored. Sophia, wife to Mathias. Hilario, servant to Sophia. NOTES ON THE ANNOTATIONS Corisca, Sophia's woman. Julio Baptista, a great scholar. References in the annotations to Gifford refer to the notes supplied by editor W. -

Living with Stories

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Living With Stories William Schneider Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schneider, W. S., & Crowell, A. (2008). Living with stories: Telling, re-telling, and remembering. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Living with Stories Telling, Re-telling, and Remembering Living with Stories Telling, Re-telling, and Remembering Edited by William Schneider With Essays by Aron L. Crowell and Estelle Oozevaseuk Holly Cusack-McVeigh Sherna Berger Gluck Lorraine McConaghy Joanne B. Mulcahy Kirin Narayan Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free, recycled paper ISBN 978–0–87421–689-9 (cloth) ISBN 978–0–87421–690-5 (e-book) Chapter 3 was fi rst published as Aron L. Crowell and Estelle Oozevaseuk. 2006. “The St. Lawrence Island Famine and Epidemic, 1878–1880: A Yupik Narrative in Cultural and Historical Perspective.” Arctic Anthropology 43(1):1–19. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Living with stories : telling, re-telling, and remembering / edited by William Sch- neider ; with essays by Aron L. Crowell ... [et al]. -

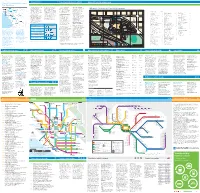

Monash University Caulfield Campus

Monash University Caulfield campus Travel Smart Travelling to Monash Caulfield Monash Caulfield campus map Monash University Caulfield campus TravelSmart map Caulfield campus is located Monash has good reason Choosing sustainable Cycling to Caulfield in an urban area with to care about your travel transport has never Why not cycle to Monash Monash University Caulfield campus limited parking spaces, so choices! With limited been easier! A range of University’s Caulfield driving isn’t always going space available at Caulfield travel options is available campus? You can stay 1 2 3 4 to be the easiest option. campus, every new car park for getting to and from fit and healthy, and it can Building index Building On the plus side, Caulfield that Monash has to provide Caulfield campus. be quicker than other Access Monash B4 F Information Technology Office of the Vice-Provost By train and tram: The Caulfield Railway To St Kilda Computer Laboratories B3 B,K,T (Social Inclusion) B4 F Station is adjacent to the campus, and has great sustainable costs $20,000 and takes up Accounting A3 H transport options. and City Street Finch Bates Street Street Turner Epping Street Street Douglas Clarence Street Clarence four lines stop at the station: Cranbourne, Caulfield Train Station Road Burke Interior Architecture B3 E Overseas Student Services transport options, room that could be used for Architecture B4 F Dandenong, Frankston and Pakenham. (OSS) Lounge B2 S Languages, Literatures, The No. 3 tram from Swanston Street will particularly public transport. a new laboratory or lecture Why not jump on a train? Cycling routes are marked Waverley Road Waverley Road Art, Design and Architecture B3 G A A Cultures and Linguistics B3 C Parenting/Disability Room B2 S also take you directly to Caulfield campus. -

The Literary Studies Convention @ Wollongong University 7 – 11 July 2015

1 The Literary Studies Convention @ Wollongong University 7 – 11 July 2015 with the support of AAL, the Australasian Association of Literature ASAL, the Association for the Study of Australian Literature AULLA, the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association The Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts School of the Arts, English and Media English and Writing Program University of Wollongong and Cengage Learning Maney Publishing The convention venues are Buildings 19, 20 and 24 of the University of Wollongong. The Barry Andrews Memorial Lecture and Prize-Giving will be in the Hope Lecture Theatre (Building 43) ** Please note that some books by delegates and keynote speakers will be for sale in the University of Wollongong’s Unishop in Building 11. Look for the special display for the Literary Networks Convention. 2 3 Barry Andrews Memorial Address: Tony Birch .......................................................................... 10 Keynote Address: Carolyn Dinshaw ............................................................................................. 11 Keynote Address: Rita Felski ......................................................................................................... 12 Dorothy Green Memorial Lecture: Susan K. Martin .................................................................. 13 Plenary Panel: Australia’s Literary Culture and the Australian Book Industry ....................... 14 Plenary Panel: Literary Studies in Australian Universities – Structures and Futures ........... 16 Stephen -

Read the 34 Letters to Paul Carron. Pgs 187-304

: 8. LETTERS TO PAUL CARRON Paul Carron studied at the Seminary of St. Sulpice in Paris and was quickly noticed on account of his outstanding piety and talents. Immediately after his ordination, he be- came secretary to the Archbishop of Paris. The numerous letters Father Libermann addressed to him indicate the last- ing spiritual friendship between those two zealous men. 123 Trials draw us closer to Jesus. Letter One lssy, September 21, 1836 Vol. 1, p. 324 Dear Confrere May the good Lord preserve you in His peace and most holy love. You probably blame me very much for having received your two letters and not having answered a single one of them. It is unpardonable, isn't it? And yet it is not a great fault on my part. I would have replied immediately after I had received your first letter, but I had to leave a few days later. I thought I would be able to see you before my letter would have reached you, for I reckoned that you would re- main at lssy during the whole Octave, and my letter would have reached your place during your absence. Regarding the second, I wanted absolutely to send you the enclosed papers, and they were not ready at that time. Mr. de la Bruniere. who had the job of copying them, was somewhat behind in his task. Anyhow, provided you love God, and I also, we can both of us be satisfied. I should have been very glad to see you at lssy. One of the reasons why I hastened to leave Strasbourg was that I might come in time; God did not wish it. -

Kim Scott's Writing and the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Project

Disputed Territories as Sites of Possibility: Kim Scott's Writing and the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Project Natalie Quinlivan BA International Studies, BA Communications (Creative Writing), MA English A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences School of Literature, Art and Media University of Sydney April 2019 Abstract Kim Scott was the first Aboriginal author to win the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2000 for Benang, an award he won again in 2011 for That Deadman Dance. Yet despite these national accolades, Scott interrogates the very categories of Australian and Indigenous literatures to which his work is subjected. His writing reimagines, incorporates and challenges colonial ways of thinking about people and place. This thesis reveals the provocative proposal running through Scott’s collected works and projects that contemporary Australian society (and literature) should be grafted onto regional Aboriginal languages and stories as a way to express a national sense of “who we are and what we might be”. Scott’s vision of a truly postcolonial Australia and literature is articulated through his collected writings which form a network of social, historical, political and personal narratives. This thesis traces how Scott’s writing and the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Project (Wirlomin Project) reconfigure colonial power relationships in the disputed territories of place, language, history, identity and the globalised world of literature. Ultimately, Scott intends to create an empowered Noongar position in cross-cultural exchange and does so by disrupting the fixed categories inherent in these territories; territories constructed during the colonising and nationalising of Australia. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

18 November 1984 CHART #452 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I Just Called To Say I Love You Hard Habit To Break The Unforgettable Fire Under A Blood Red Sky 1 Stevie Wonder 21 Chicago 1 U2 21 U2 Last week 1 / 6 weeks Gold / POLYGRAM Last week 32 / 3 weeks WEA Last week 1 / 3 weeks Platinum / ISLAND/POLYGRAM Last week 18 / 38 weeks Platinum / ISLAND/POLYGRAM Ghostbusters Dancing In The Dark Heartbeat City Pleasure Victims 2 Ray Parker Jnr 22 Bruce Springsteen 2 The Cars 22 Berlin Last week 2 / 8 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 20 / 21 weeks CBS Last week 2 / 32 weeks Platinum / WEA Last week 15 / 29 weeks Gold / POLYGRAM Careless Whisper Freedom Born In The U.S.A. Can't Slow Down 3 George Michael 23 Wham 3 Bruce Springsteen 23 Lionel Richie Last week 3 / 9 weeks CBS Last week - / 1 weeks CBS Last week 3 / 22 weeks Platinum / CBS Last week 31 / 44 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM We're Not Gonna Take It She Bop The Woman In Red This Island 4 Twisted Sister 24 Cyndi Lauper 4 Stevie Wonder 24 Eurogliders Last week 13 / 3 weeks WEA Last week 21 / 10 weeks CBS Last week 5 / 6 weeks Gold / POLYGRAM Last week 27 / 6 weeks CBS Pride Smooth Operator See Ya Round An Innocent Man 5 U2 25 Sade 5 Split Enz 25 Billy Joel Last week 4 / 8 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 25 / 6 weeks CBS Last week 9 / 2 weeks Gold / FESTIVAL Last week 28 / 58 weeks Platinum / CBS The War Song No More Lonely Nights Stop Making Sense Rebel Yell 6 Culture Club 26 Paul McCartney 6 Talking Heads 26 Billy Idol Last week 5 / 4 weeks VIRGIN Last week 28 / 3 weeks EMI Last week 4 / 4 weeks EMI Last week 33 / 31 weeks Platinum / FESTIVAL Cover Me Dancin' In Berlin The Optimist Legend 7 Bruce Springsteen 27 Berlin 7 D.D. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

HIP-HOP LIFE AND LIVELIHOOD IN NAIROBI, KENYA By JOHN ERIK TIMMONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 John Erik Timmons To my parents, John and Kathleen Timmons, my brothers, James and Chris Timmons, and my wife, Sheila Onzere ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of a PhD requires the support of many people and institutions. The intellectual community at the University of Florida offered incredible support throughout my graduate education. In particular, I wish to thank my committee members, beginning with my Chair Richard Kernaghan, whose steadfast support and incisive comments on my work is most responsible for the completion of this PhD. Luise White and Brenda Chalfin have been continuous supporters of my work since my first semester at the University of Florida. Abdoulaye Kane and Larry Crook have given me valuable insights in their seminars and as readers of my dissertation. The Department of Anthropology gave me several semesters of financial support and helped fund pre-dissertation research. The Center for African Studies similarly helped fund this research through a pre-dissertation fellowship and awarding me two years’ support the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship. Another generous Summer FLAS Fellowship was awarded through Yale’s MacMillan Center Council on African Studies. My language training in Kiswahili was carried out in the classrooms of several great instructors, Rose Lugano, Ann Biersteker, and Kiarie wa Njogu. The United States Department of Education generously supported this fieldwork through a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award. -

Club and AFL Members Received Free Entry to NAB Challenge Matches and Ticket Prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series Were Held at 2013 Levels

COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS DARREN BIRCH GENERAL MANAGER Club and AFL members received free entry to NAB Challenge matches and ticket prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series were held at 2013 levels. eason 2015 was all about the with NAB and its continued support fans, with the AFL striving of the AFL’s talent pathway. to improve the affordability The AFL welcomed four new of attending matches and corporate partners in CrownBet, enhancing the fan experience Woolworths, McDonald’s and 2XU to at games. further strengthen the AFL’s ongoing SFor the first time in more than 10 development of commercial operations. years, AFL and club members received AFL club membership continued free general admission entry into NAB to break records by reaching a total of Challenge matches in which their team 836,136 members nationally, a growth was competing, while the price of base of 3.93 per cent on 2014. general admission tickets during the In season 2015, the Marketing and Toyota Premiership Season remained the Research Insights team moved within the same level as 2014. Commercial Operations team, ensuring PRIDE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Fans attending the Toyota AFL Finals greater integration across membership, The Showdown rivalry between Eddie Betts’ Series and Grand Final were also greeted to ticketing and corporate partners. The Adelaide Crows and Port ticket prices at the same level as 2013, after a Research Insights team undertook more Adelaide continued in 2015, price freeze for the second consecutive year. than 60 projects, allowing fans, via the with the round 16 clash drawing a record crowd NAB AFL Auskick celebrated 20 years, ‘Fan Focus’ panel, to influence future of 53,518.