Tuzla, the Third Side, and the Bosnian War by Joshua N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuzla Is a City in the Northeastern Part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It Is the Seat of the Tuzla Canton and Is the Econo

Summary: Tuzla is a city in the northeastern part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the seat of the Tuzla Canton and is the economic, scientific, cultural, educational, health and tourist centre of northeast Bosnia. Preliminary results from the 2013 Census indicate that the municipality has a population of 120,441. District Heating System of Tuzla City started in October 1983. Project to supply Tuzla City with heat energy from Tuzla Power Plant that will have combined production of electricity and heat was happened in 4 phases. The requirements for connection to Tuzla District Heating brought of system in position that in 2005 we got to the maximum capacity and we had to do wide modernization of network pipes and heat substations. Facts about the Tuzla district energy system Annual heat carrying capacity: 300,000 MWth Temperature: 130–60°C Transmission network length: 19.6 km (2x9.8 km) Distribution network length: 142.4 km (2x71.2 km) Power station fuel: Coal Number of users: Total: 22934 Flats snd Houses: 20979 Public Institutions: 156 Commercial units: 1799 Heated area (square meters): Total: 1718787 Flats and Houses: 1158402 Public Institutions: 220460 Commercial units: 339925 Results achieved by reengineering the Tuzla district energy system • 30 % energy savings compared to old system before retrofit • Capacity expanded by 36 % within the existing flow of 2,300 m3/h • Reengineering of 98 substations: ball valves, strainers, pressure regulators, control valves, temperature and pressure sensors, safety thermostats, weather stations, electronic controllers, thermostatic radiator valves (TRVs), energy meters Tuzla is a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the seat of the Tuzla Canton and is the economic, scientific, cultural, educational, health and tourist centre of northeast Bosnia. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Joint Opinion on the Legal

Strasbourg, Warsaw, 9 December 2019 CDL-AD(2019)026 Opinion No. 951/2019 Or. Engl. ODIHR Opinion Nr.:FoA-BiH/360/2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS (OSCE/ODIHR) BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JOINT OPINION ON THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING THE FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, IN ITS TWO ENTITIES AND IN BRČKO DISTRICT Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 121st Plenary Session (Venice, 6-7 December 2019) On the basis of comments by Ms Claire BAZY-MALAURIE (Member, France) Mr Paolo CAROZZA (Member, United States of America) Mr Nicolae ESANU (Substitute member, Moldova) Mr Jean-Claude SCHOLSEM (substitute member, Belgium) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2019)026 - 2 - Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 II. Background and Scope of the Opinion ...................................................................... 4 III. International Standards .............................................................................................. 5 IV. Legal context and legislative competence .................................................................. 6 V. Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 8 A. Definitions of public assembly .................................................................................. -

New FPL 2012 Planning and Implementation Bosnia and Herzegovina

BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FEDERACIJA BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE FEDERATION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FEDERALNO MINISTARSTVO PROMETA I KOMUNIKACIJA FEDERAL MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS FEDERALNA DIREKCIJA ZA CIVILNO ZRAKOPLOVSTVO - FEDERALNA DIREKCIJA ZA CIVILNU AVIJACIJU FEDERAL CIVIL AVIATION DEPARTMENT New FPL 2012 Planning and Implementation Bosnia and Herzegovina 1. Bosnia and Herzegovina – Overview Bosnia and Herzegovina has been in IFPS zone as of 23rd December 2004. This significantly improved the ATS, over the years as well as today when the new FPL format needs to be used as of November 2012. Bosnia and Herzegovina civil aviation authorities and agencies are responsible of air navigation services at four airports, Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla and Banja Luka. The FIR Sarajevo area control has been still served by CCL (Croatia) and SMATSA (Serbia). The BiH civil aviation activities are in short organised as follows: FEDCAD BHANSA BHDCA RSCAD Coordination ATC Projects ATC Sarajevo, Mostar, Delegation Delegation Banja Luka Tuzla Project New FPL Project New FPL 2012 2012 New FPL 2012 ATS Server En route DPS ATS Server Convertor LQQQ Training Charge Office ATC Sarajevo Training AISBH/ARO/ DPS ARO/ATCO ATCO Project /training Coordination Dr Ante Starčevića bb, 88000 Mostar Tel: +387 (0) 36 449-230 Dr. Ante Starcevica bb, 88000 Mostar Poštanski pretinac 92, 88101 Mostar Fax: +387 (0) 36 327-811 Post Office Box 92, 88101 Mostar Bosna i Hercegovina E-mail: [email protected] Bosnia and Herzegovina http://www.fedcad.gov.ba 1/5 BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FEDERACIJA BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE FEDERATION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FEDERALNO MINISTARSTVO PROMETA I KOMUNIKACIJA FEDERAL MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS FEDERALNA DIREKCIJA ZA CIVILNO ZRAKOPLOVSTVO - FEDERALNA DIREKCIJA ZA CIVILNU AVIJACIJU FEDERAL CIVIL AVIATION DEPARTMENT BHDCA is the state organisation, civil aviation authorities responsible of the air navigation services for Bosnia and Herzegovina. -

Jasmina Osmankovic Ph. D. Institute for Sarajevo Development Planning Sarajevo, Bosnia -Herzegovina Tel: +387 66 142 862

Jasmina Osmankovic Ph. D. Institute for Sarajevo Development Planning Sarajevo, Bosnia -Herzegovina Tel: +387 66 142 862 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA Contents Abstract Why regional development of Bosnia -Herzegovina Theory of regional development Theory of regional development in papers of BiH authors Issues of regional development in papers of BiH authors ú Region ú Regional centers ú Regionalization ú Concentration and polarization ú Development of underdeveloped regions ú Territorial organization ú Evolution of regional development Regional policy in XX century Present picture of the regional structure Regional policy in XXI century Abstract Justification for dealing with the regional development of Bosnia -Herzegovina lays in its importance for Bosnia -Herzegovina or the possibilities to contribute to the efficiency of global development process, elimination of underdevelopment, decreasing the differences in development level, generating and accelerating the development itself by using adequate strategy and policy of regional development. Strong cause-consequence relationship of regional development and sustainable, humane development, or Comprehensive Development Framework (CDF further on) is not less important, especially in context of B&H obligations to implement the documents adopted on the world and European level in period from 1992 to 2001. Additional arguments for choosing this topic can be found also in the importance of regional development while profiling the development for the next century in context of new political moments. Bosnia -Herzegovina, as an independent, sovereign and internationally recognized country is fully responsible for its entire development. Issues of regional development, especially the regionalization of Bosnia -Herzegovina have been elaborated thoroughly and for a long time in papers of B&H authors, that represents solid foundations for the development policy in the second half of XX century. -

WAR WASTE and POLLUTION of KARSTIC AREA of BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA with Pcbs

LEVELS IN SOIL AND WATER WAR WASTE AND POLLUTION OF KARSTIC AREA OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA WITH PCBs NENA PICER1, Neven Miošić2, Vedranka Hodak-Kobasić1, Tanja Kovač1, Violeta Čalić1, Hasim Hrvatović2 1Rudjer Boskovic Institute, Zagreb 2Geological survey, Sarajevo Introduction During the recent war, the karst area of Bosnia & Herzegovina has been jeopardized by hazardous waste and deserves particular attention because of its exceptional ecological sensitivity and unfortunately unscrupulous destruction of natural resources, infrastructure, homes and enterprises. This was the reason for creation and planning of a joint three year Project – APOPSBAL, within which scientists from the jeopardized countries (Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, and Serbia and Montenegro) with the help of scientists from other friendly countries (Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia and Greece) would identify the real problems concerning the PCB and other POPs contamination of the environment1. Objectives of this Project in Bosnia and Herzegovina are: 1) To collect data about damaged facilities with oil with PCBs and also other even more dangereous POPs in Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2) Much better determining the hydrogeological fate of PCBs and other POPs compounds in the most threatened areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina polluted with the POPs. Special emphasis will be paid for the sensitive karstic media of these areas. 3) To recognize in the field directly the technical state of electrotransformers and capacitors with pyralene with special attention to spilling of this oil into the environment. 4) To sample soil and sediments from the sites thought polluted with PCBs and to analyse themselves on its content. 5) To choose several sites for atmospheric monitoring samples with POPs, which are in surroundings to the ground argumentative contaminated with POPs in Bosnia and Herzegovina to establish real data about level of contamination of this very important part of human ecosphere. -

Novi Grad Sarajevo Sarajevo MN MAC

BUSINESS FRIENDLY MUNICIPALITY SOUTH EAST EUROPE CRO Novi Grad BiH SER Novi Grad Sarajevo Sarajevo MN www.novigradsarajevo.ba MAC Location Bosnia and Herzegovina, 43°84’N 18°37’E Border Crossings Montenegro (68 km), Croatia (102) Population 130.000 Territory 47,8 km²; 44,5% arable land, 26,4% forests, 29,1% roads and other Budget € 19,5 million, 46% of capital investments Contact Bulevar Meše Selmovića 97, 71.000 Sarajevo, +387 33 291 100, [email protected] is the most populated municipality in BiH and the Novi Grad Sarajevo Vienna (774 km) “entrance gate” to Sarajevo from Corridor Vc. Being in close proximity to the international airport in Sarajevo, Corridor Vc and international Budapest (551 km) sea ports in the Mediterranean, Novi Grad Sarajevo holds a highly favorable geographic position, with easy access to local and regional Zagreb markets. With continuous investments in infrastructure and capital (401 km) investments reaching the value of more than 50% of its annual budget, the municipality stands out as a modern and favorable place for living and doing business. Educated, qualified and young workforce, fully Belgrade (344 km) equipped industrial and business zones and local incentives strongly Milan recommend Novi Grad Sarajevo as an investment location. The (1.028 km) municipality has already welcomed investors in traditional and new industries such as automotive, chemical, processing, food, and ICT. The local community has been recording continuous progress in terms Sofia (583 km) of construction due to its vast spatial potentials and a vivid business, NOVI GRAD Istanbul cultural and tourism scene, being surrounded by four mountains. -

R/B Dobavljač

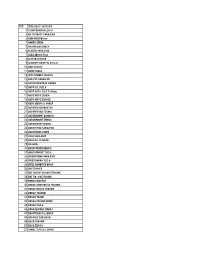

R/B Dobavljač/ vjerovnik 1 15.OKTOBAR KALESIJA 2 AB TECHNICS SARAJEVO 3 ACM-SOKO Mostar 4 AHMED ĆERIM 5 AKVARIJUM ZENICA 6 ALADŽA SARAJEVO 7 ALBA ZENICA Total 8 ALFE-MI ŽIVINICE 9 ALGRAPH GRAFI¬KI ATELJE 10 AMK ŽIVINICE 11 AMOS TUZLA 12 APELPROMET TRAVNIK 13 ASA PSS SARAJEVO 14 ASVALTGRADNJA VISOKO 15 AUTO DJL TUZLA 16 AUTO KUĆA JELIĆ Š. Brijeg 17 AUTO MOTO ZENICA 18 AUTO MOTO ŽIVINICE 19 AUTO SERVIS D. VAKUF 20 AUTOPREVOZ MOSTAR 21 AUTOPREVOZ TEŠANJ 22 AUTOREMONT BANOVIĆI 23 AUTOREMONT ZENICA 24 AUTOSERVIS VISOKO 25 AUTOTEHNA SARAJEVO 26 AUTOTRANS VAREŠ 27 AVAZ SARAJEVO 28 BALD DJL KLADANJ 29 BEHAPOL 30 BEKOSTRADE ZENICA 31 BENZ KOMERC TUZLA 33 BIROOPREMA SARAJEVO 34 BIROTEHNIKA TUZLA 35 BITEX KOMBITEX BIHAĆ 36 BKC ŽIVINICE 37 BNT BRATSTVO NOVI TRAVNIK 38 BNT TM I H N.TRAVNIK 39 BONSAI MOSTAR 40 BORAC KONFEKCIJA TRAVNIK 41 BORAC OBUĆA TRAVNIK 42 BORAC TRAVNIK 43 BOSKO TRADE 44 BOSNA PREVOZ DOBOJ 45 BOSNA TUZLA 46 BOSNAEXPRES DOBOJ 47 BOSSTRANS DJL BIHAĆ 48 BOSSVEZ SARAJEVO 49 BUCO TRAVNIK 50 BUCO ZENICA 51 CAMEL TURS DJL BIHAĆ 52 CAPROMET BIHAĆ 54 CENRALNO GRIJANJE JKP TUZLA 55 CENTAR ZA ZAŠTITU OD POŽ.ZENICA 56 CENTAR ZA ZAŠTITU OD POŽAR 57 CENTRAL TUZLA 60 CENTROTRANS BUS VISOKO 61 CENTROTRANS VISOKO 62 COSMOS D.O.O. SARAJEVO 63 CREATION SARAJEVO 64 CVJEĆARA NARCIS 65 Ćićak Muđugorje 66 DD FOTO OPTIK SARAJEVO 67 DEFTER SARAJEVO 68 DIJAMANT SARAJEVO 69 DIONIS ZENICA 70 DIREKC.ZA PROS.URE.I IZG.ŽIVINICE 71 DITA TUZLA 72 DIZART AGENCIJA SARAJEVO 73 DOM PENZIONERA ZENICA 74 DOM ŠTAMPE ZENICA 76 DOM ZDRAVLJA BUGOJNO 77 DOM ZDRAVLJA D. -

Youth Essay Competition “Tackling Youth Unemployment in Bosnia and Herzegovina: My Generation's View” List of All Particip

Youth Essay Competition “Tackling Youth Unemployment in Bosnia and Herzegovina: My Generation’s View” List of All Participants of the Competition Names 1. Admir Čavalić, Tuzla 2. Admir Karadža, Bugojno 3. Admira Tahirović, Sarajevo 4. Adnan Muminović, Sarajevo 5. Aida Mujezinović, Tešanj 6. Aida Sadagić, Sarajevo 7. Ajdin Čagalj, Sarajevo 8. Ajdin Perčo, Sarajevo 9. Ajka Baručić and Lejla Ahmetagić, Tuzla 10. Ajla Kurspahić, Sarajevo 11. Alaudina Boškailo, Čapljina 12. Albinko Hasić 13. Aleksandar Crnovčić, Banja Luka 14. Aleksandar Jovanović, Ugljevik 15. Aleksandra Gojić, Doboj 16. Alen Džananović, Sarajevo 17. Alija Bajramović, Sarajevo 18. Amela Habibić, Turbe 19. Amila Biogradlija, Zenica 20. Amila Pozderac, Bihać 21. Amra Kandić 22. Anamarija Ljubić, Široki Brijeg 23. Anela Zorlak, Goražde 24. Anesa Omanović, Sarajevo 25. Arslan Berbić, Tuzla 26. Azra Aljkanović, Sarajevo 27. Belmin Selimbegović, Sarajevo 28. Berina Kapetanović, Sarajevo 29. Berina Porča, Sarajevo 30. Biljana Popović, Banja Luka 31. Boban Sašić, Kneževo 32. Boris Drobić, Brčko 33. Boris Lalić, Sarajevo 34. Boriša Stevanović, Bijeljina 35. Branko Vasiljević, Banja Luka 36. Damir Kurtagić, Sarajevo 37. Dario Milić 38. Divna Kosović, Mostar 39. Dragana Krcum, Mostar 40. Dragana Marinković, Budapest, Hungary 41. Dragana Pavlović, Bijeljina 42. Elvira Ganibegović 43. Dženita Hukić, Sarajevo 44. Ediba Softić, Tuzla 45. Edin Pašović, Sarajevo 46. Edvin Sinanović, Zavidovići 47. Elma Cuprija, Visoko 48. Ema Mustafić, Bihać 49. Emil Ahmagić, Sarajevo 50. Emina Čamdžić, Sarajevo 51. Emina Rekanović, Sarajevo 52. Emina Vranić, Sarajevo 53. Emir Šabanić, Sarajevo 54. Ena Muratspahić, Sarajevo 55. Enes Tinjić, Tuzla 56. Evelin Trako, Sarajevo 57. Fahira Brodlija, Sarajevo 58. Fatima Muhamedagić, Pećigrad 59. Haris Softić, Tuzla 60. -

Department for Legal Affairs CONSTITUTION of TUZLA CANTON

Emerika Bluma 1, 71000 Sarajevo Tel. 28 35 00 Fax. 28 35 01 Department for Legal Affairs CONSTITUTION OF TUZLA CANTON “Official Gazette of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton”, 7/97 NOTE: 1. Amendments to the Constitution of Tuzla Canton, published in the “Official Gazette of Tuzla Canton”, 3/99, 13/99, 10/00, 14/02 and 6/04 are not included in this translation. 2. By the Sentence of the Constitutional Court of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, U-14/98, published in the “Official Gazette of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton”, 8/98, Article 4, Paragraph 1, is not in accordance with the Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 3. * By the Amendment I on the Constitution of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton, published in the “Official Gazette of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton”, 3/99, Article 4, Paragraph 1. of the Constitution of Tuzla, are changing and it should be read as it follows: “The name of the Canton is: Tuzla Canton”. Having strong belief that democratic institutions, operating on the base of respecting human rights and freedoms best ensure the harmony between themselves and their community; refusing the violence of war; improving peace, individual freedom, economical development through protection of private property and market economy; led by the principles of the United Nations Charter on Human Rights and General Frame- work Peace Agreement for Bosnia and Herzegovina and* its Annexes; The assembly of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton, a federal unit of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Bosniak and Croat peoples and citizens of Tuzla-Podrinje Canton were presented, being determined to ensure full national equality, democratic relations and highest standards of human rights and freedoms, on the basis of Article V 1.4. -

Remarks to the Troops in Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina December 22

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1997 / Dec. 22 2099 Croats, and Serbs. Well, they're still here, guished military officials and officials from and they're still Muslims, Croats, and Serbs. the White House; and a truly astonishing del- And to tell you the truth, I know the tuba egation from Congress, of both Democrats players from the violinists, but I can't tell the and Republicans together. Muslims from the Croats from the Serbs. We have Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska; The harmony of their disparate voicesÐthe Senator Joe Biden of Delaware; Senator Joe harmony of their disparate voicesÐis what Lieberman of Connecticut; Senator Dan I hear. It reminds me of Bosnia's best past, Coats of Indiana; Representative John Kasich and it should be the clarion call to your fu- of Ohio; Representative Jack Murtha of ture. Pennsylvania; Representative Ike Skelton of Here at the dawn of the new millennium, Missouri; Representative Elijah Cummings let us recall that the century we are leaving of Maryland; Representative Mac Collins of began with the sound of gunfire in Sarajevo. GeorgiaÐanybody from Georgia? [Cheers] And let us vow to start the new century with Representative John Boehner of Ohio and the music of peace in Sarajevo. Representative Steve Buyer of IndianaÐany- To the people of Bosnia I say, you have body here from Indiana? [Cheers] I'm proud seen what war has wrought; now you know of all of them. what peace can bring. So seize the chance And let me say, we came here for two rea- before you. You can do nothing to change sons today. -

Floods in Bosnia and Herzegovina ECHO JOINT ASSESSMENT REPORT Shortage

Floods in Bosnia and Herzegovina ECHO JOINT ASSESSMENT REPORT shortage 06/06/2014, Map 08:00:00 UTC Status Request for assistance. Event Floods Occurrence Date: 15/05/2014 Time: 16:38 UTC Recommendations Short term actions The Civil Protection response operations are gradually coming to an end. Water purification and debris removal are still on-going and will most probably continue for the next days. Rehabilitation and reconstruction of public buildings and services (health ECHO Emergency centers, schools, public administrative buildings and institutions Contact Tel.: +32 2 29 21112 Shelter and housing – cleaning, rehabilitation and repair of a total of Fax: +32 2 29 86651 25.000 priority dwellings [email protected] Debris management – solid waste and debris removal ECHO Joint Mission Report – Bosnia and Herzegovina floods Page 1 of 10 Infrastructure: Roads & Bridges – repair and replacement Water, Sanitation and sewage – restoring water supply and sewage systems Livelihoods and agriculture – Assistance to bring back on line industrial and small scale farming, planting and soil decontaminations The overall estimate of the cost of the above mentioned priorities is USD 153 million (UN source). Comprehensive disaster waste management response to be carried out in order to clear the affected areas. Due to infiltration of waste water into wells a comprehensive assessment of water quality needs to be carried out (including private wells). Mid-term to Long-term actions: • An awareness campaign should be conducted in all flood affected areas regarding the mine and UXO situation. Once the flooded areas are dry the assessment of possible movements of mines/UXO in the already listed minefields should begin and be carried out by BHMAC and their partners, priority should be given to populated areas. -

Phylogenetic Pattern of SARS-Cov-2 from COVID-19 Patients from Bosnia and Herzegovina: Lessons Learned to Optimize Future Molecular and Epidemiological Approaches

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.19.160606; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Phylogenetic pattern of SARS-CoV-2 from COVID-19 patients from Bosnia and Herzegovina: lessons learned to optimize future molecular and epidemiological approaches Teufik Goletic1, Rijad Konjhodzic2, Nihad Fejzic1, Sejla Goletic1, Toni Eterovic1, Adis Softic1, Aida Kustura1, Lana Salihefendic2, Maja Ostojic3, Maja Travar4, Visnja Mrdjen4, Nijaz Tihic5, Sead Jazic6, Sanjin Musa7, Damir Marjanovic8,9, Mirsada Hukic10 Correspondence: Teufik Goletic ([email protected]) 1. Veterinary faculty of University of Sarajevo, Zmaja od Bosne 90, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2. ALEA Genetic Center, Olovska 67, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 3. University Clinical Hospital of Mostar, Bijeli Brijeg b.b., 88000 Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina 4. University Clinical Centre of the Republic of Srpska, Dvanaest beba bb, 78000 Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina 5. University Clinical Center Tuzla, Ulica Profesora doktora Ibre Pašića, 75000 Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina 6. General Hospital "Abdulah Nakas", Kranjceviceva 12, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 7. Institute for Public Health of Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Marsala Tita 9, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 8. Center for Applied Bioanthropology, Institute for Anthropological Researches, Gajeva ulica 32, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia 9. Department of Genetics and Bioengineering, Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, International Burch University, Francuske revolucije bb, 71 000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 10.