IT's HARD and NOBODY UNDERSTANDS: Annotations And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel Universe by Hasbro

Brian's Toys MARVEL Buy List Hasbro/ToyBiz Name Quantity Item Buy List Line Manufacturer Year Released Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 13, 2015 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: Referred By (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very important that we Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By following the below format, you will help Selling Your Collection ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Marvel/toys . STEP 1 Please note: Yellow fields are user editable. You are capable of adding contact information above and quantities/notes below. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Marvel category. Search for each of your items and enter the quantity you want to sell in column I (see red arrow). (A hint for quick searching, press Ctrl + F to bring up excel's search box) The green total column will adjust the total as you enter in your quantities. -

Gang Definitions, How Do They Work?: What the Juggalos Teach Us About the Inadequacy of Current Anti-Gang Law Zachariah D

Marquette Law Review Volume 97 Article 6 Issue 4 Summer 2014 Gang Definitions, How Do They Work?: What the Juggalos Teach Us About the Inadequacy of Current Anti-Gang Law Zachariah D. Fudge [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Zachariah D. Fudge, Gang Definitions, How Do They Work?: What the Juggalos Teach Us About the Inadequacy of Current Anti-Gang Law, 97 Marq. L. Rev. 979 (2014). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol97/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUDGE FINAL 7-8-14 (DO NOT DELETE) 7/9/2014 8:40 AM GANG DEFINITIONS, HOW DO THEY WORK?: WHAT THE JUGGALOS TEACH US ABOUT THE INADEQUACY OF CURRENT ANTI-GANG LAW Precisely what constitutes a gang has been a hotly contested academic issue for a century. Recently, this problem has ceased to be purely academic and has developed urgent, real-world consequences. Almost every state and the federal government has enacted anti-gang laws in the past several decades. These anti-gang statutes must define ‘gang’ in order to direct police suppression efforts and to criminally punish gang members or associates. These statutory gang definitions are all too often vague and overbroad, as the example of the Juggalos demonstrates. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

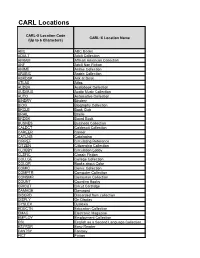

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Il Fumetto Digitale Tra Sperimentazione E Partecipazione: Il Caso Homestuck

H-ermes. Journal of Communication H-ermes, J. Comm. 18 (2020), 45-72 ISSN 2284-0753, DOI 10.1285/i22840753n18p45 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it Il fumetto digitale tra sperimentazione e partecipazione: il caso Homestuck Giorgio Busi Rizzi Digital comics halfway between experimentation and participation: the example of Homestuck. Digital comics that try to maximize the affordances of their medium seem to be condemned to in-betweenness: their strength (leveraging on unusual narrative potentials) often becomes their limit, and authors are hardly able to free themselves from the role of niche experimenters and open up to audience participation. A significant exception, however, is Homestuck, a gigantic webcomic by Andrew Hussie. Strongly connected to videogame culture and the very nature of the internet, Homestuck features animations, sounds, embedded flash games, and so on. The webcomic resulted in various transmedial branches (a videogame spin-off and several friendsims, a multi-volume soundtrack, a book epilogue) and an ongoing intermedial adaptation in book format. It has equally managed, over the years, to consolidate an extremely lively community active both in its interactions with the author (with a constant exchange of ideas and an endless readiness to subsidize his projects), in its interpretation of the canon production, and in providing an amazing extent of fan production. This contribution aims to analyze Homestuck as a possible mediation between the two inclinations (experimental and participated) of digital comics. Keywords: webcomics; Homestuck, transmedia, fan studies, digital comics. Introduzione Leggendo certa critica (accademica e non), il fumetto digitale pare godere di una sorta di eterna giovinezza: un medium eternamente potenziale, eternamente nuovo, eternamente sul punto di soppiantare la carta. -

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1992 Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hillis, Lisa, "Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings" (1992). Masters Theses. 2182. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2182 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for i,\1.clusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for iqclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Ef\i.stern Illinois University not allow my thes~s be reproduced because --------------- Date Author m Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings (TITLE) BY Lisa Hillis THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DECREE OF Master .of Arts 11': THE GRADUATE SCHOOL. -

Revue De Recherche En Civilisation Américaine, 6

Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine 6 | 2016 Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations Women and Comics, Authorships and Representations Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 ISSN : 2101-048X Éditeur David Diallo Référence électronique Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016, « Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 19 décembre 2016, consulté le 16 mars 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 mars 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Editorial Amélie Junqua et Céline Mansanti Women Comics Authors in France and Belgium Before the 1970s: Making Them Invisible Jessica Kohn L’autoreprésentation féminine dans la bande dessinée pornographique Irène Le Roy Ladurie Empowered et le pouvoir du fan service Alexandra Aïn Women W.a.R.P.ing Gender in Comics: Wendy Pini’s Elfquest as mixed power fantasy Isabelle L. Guillaume A 21st Century British Comics Community that Ensures Gender Balance Nicola Streeten Hors thème Book review Sabbagh, Daniel. L’égalité par le droit, les paradoxes de la discrimination positive aux Etats- Unis Paris, Economica, collection « Etudes Politiques », 2003 [2007], 458 p. Laure Gillot-Assayag Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016 2 Editorial Amélie Junqua and Céline Mansanti 1 Aux Etats-Unis, les utilisatrices de Facebook représentent aujourd’hui 53% des utilisateurs de Facebook qui lisent de la bande dessinée, 40% de plus qu’il y a trois ans. Pourtant, moins de 30% des personnages et des écrivains de BD sont des femmes, même si ces chiffres progressent également (http://www.ozy.com/acumen/the-rise-of-the- woman-comic-buyer/63314). -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer

A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY By Michael Buso A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the fundamental assistance of Barclay Barrios, the hours of office discourse with Eric Berlatsky, and the intellectual analysis of Don Adams. The candidate would also like to thank Robert Wertz III and Susan Carter for their patience and support throughout the writing of this thesis. iii ABSTRACT Author: Michael Buso Title: A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer Identity Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Barclay Barrios Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2010 This thesis focuses primarily on homophobia and how it plays a role in the construction of queer identities, specifically in graphic novels and comic books. The primary texts being analyzed are Alan Moore’s Lost Girls, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, and Michael Chabon’s prose novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Throughout these and many other comics, queer identities reflect homophobic stereotypes rather than resisting them. However, this thesis argues that, despite the homophobic tendencies of these texts, the very nature of comics (their visual aspects, panel structures, and blank gutters) allows for an alternative space for positive queer identities. iv A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... vi I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................. -

Bill Fawcett______24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A

Bill Fawcett___________________________________________________ 24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A. 8472779686 [email protected] Bill has been a professor, teacher, corporate executive, and college dean. His entire life has been spent in the creative fields and managing other creative individuals. He is one of the founders of Mayfair Games, a board and role play gaming company. As an author Bill has written or coauthored over a dozen books and dozens of articles and short stories. As a book packager, a person who prepares series of books from concept to production for major publishers, his company Bill Fawcett & Associates has packaged over 250 titles for virtually every major publisher. He founded, and later sold, what is now the largest hobby shop in Northern Illinois. Bill’s first commercial writing appeared as articles in the Dragon Magazine and include some of the earliest appearances of classes and monster types for dungeons and Dragons. With Mayfair Games created, wrote, and edited many of the over 50 “Role Aides” Role Playing Game modules and supplements released by Mayfair in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period he also designed almost a dozen board games, including several Charles Roberts Award (Gaming's Emmy) winners such as Empire Builder and Sanctuary. Bill Fawcett continues to develop new internet projects. His novl writing began with the juvenile series, Swordquest for Ace Penguin Putnam Publishing. He wrote or cowrote four fantasy novels, beginning with the Lord of Cragsclaw. The Fleet series he created with David Drake has become a classic of military science fiction. -

Greenbelt Elementary School Accelerated Reader Quizzes (2008 November)

Greenbelt Elementary School Accelerated Reader Quizzes (2008 November) Click on column headers to sort Title Author Level Points Food to Eat Catherine Peters 0.2 0.5 Friends Catherine Peters 0.3 0.5 In the Yard Dana Meachen Rau 0.3 0.5 Clifford Makes a Friend Norman Bridwell 0.4 0.5 My Trip to the Zoo Mercer Mayer 0.4 0.5 Willy the Helper Catherine Peters 0.4 0.5 Can You Play? Harriet Ziefert 0.5 0.5 Country Fair Mercer Mayer 0.5 0.5 Creepy Caterpillar Kana Riley 0.5 0.5 Daniel's Pet Alma Flor Ada 0.5 0.5 The Day I Had to Play with My Si Crosby Bonsall 0.5 0.5 Dogs Helen Frost 0.5 0.5 Fast-Draw Freddie (Revised Editi Bobbie Hamsa 0.5 0.5 Hats! Dana Meachen Rau 0.5 0.5 Lucky Bear Joan Phillips 0.5 0.5 Young Big Jake Dave Sargent 0.5 0.5 The B. Bears Ride the Thunderbol Stan Berenstain 0.6 0.5 Beach Day Mercer Mayer 0.6 0.5 Cats Helen Frost 0.6 0.5 Duck, Duck,Goose! (A Coyote's on Karen Beaumont 0.6 0.5 The Foot Book Dr. Seuss 0.6 0.5 Guess What? Mem Fox 0.6 0.5 I Can Do It All Mary E. Pearson 0.6 0.5 Little Big Cat Dave/Pat Sargent 0.6 0.5 Puppy Mudge Wants to Play Cynthia Rylant 0.6 0.5 Rosie's Walk Pat Hutchins 0.6 0.5 Young Brutus Dave/Pat Sargent 0.6 0.5 Young Redi Dave/Pat Sargent 0.6 0.5 Catch Me, Catch Me! Rev.