Attiéké in Côte D'ivoire at the Level of Producers, Processors, Consumers and Other User Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Project/Programme Proposal

REGIONAL PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Title of Project/Programme: Improved Resilience of Coastal Communities in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Countries: Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Thematic Focal Area: Disaster risk reduction and early warning systems Type of Implementing Entity: MIE Implementing Entity United Nations Human Settlements Programme Executing Entities: Ghana: LUSPA; NGO Côte d’Ivoire: Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Ministry of Planning and Development; NGOs Amount of Financing Requested: US$ 13,951,159 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT I. Problem statement Coastal cities and communities in West Africa are facing the combined challenges of rapid urbanisation and climate change, especially sea level rise and related increased risks of erosion, inundation and floods. For cities and communities in West Africa not to be flooded or submerged, and critically exposed to rising seas and storm surges in the next decade(s), they urgently need to increase the protection of their coastline and infrastructure, adapt to create alternative livelihoods in the inland and promote a climate change resilient urban development path. This can be done by using a combination of climate change sensitive spatial planning strategies and innovative and ecosystem-based solutions to protect land, people and assets, by implementing nature-based solutions and ‘living shorelines,’ which redirect the forces of nature rather than oppose them. The Governments of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have requested UN-Habitat to support coastal (and riverine / delta) cities and communities to better adapt to climate change. This project proposal aims at responding to this request by addressing the main challenges in these coastal zones: coastal erosion, coastal inundation / flooding and livelihoods’ resilience. -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Region Des Grands Ponts

REGION DES GRANDS PONTS 6 843 élèves 78 010 élèves 44 728 élèves AVANT-PROPOS La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DSPS/DRENET DABOU : Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la région des GRANDS PONTS 2 PRESENTATION La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la Région.Ce document présente les chiffres et indicateurs essentiels du système éducatif régional. -

Surveys on the Consumption of Attiéké (Traditional and a Commercial, Garba) in Côte D’Ivoire

Journal of Food Research; Vol. 8, No. 4; 2019 ISSN 1927-0887 E-ISSN 1927-0895 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Surveys on the Consumption of Attiéké (Traditional and a Commercial, Garba) in Côte d’Ivoire Justine Bomo Assanvo1, Georges N’zi Agbo1 & Zakaria Farah2 1Laboratory of Biochemistry and Food Science, Félix Houphouët Boigny University, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 2Institute of Food Science and Nutrition/Laboratory of Food Chemistry and Technology, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Justine Bomo Assanvo, Laboratory of Biochemistry and Food Science, UFR Biosciences, Félix Houphouët Boigny University, Abidjan, 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire. Tel: 00 225-0778-6755. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 2, 2019 Accepted: May 17, 2019 Online Published: May 31, 2019 doi:10.5539/jfr.v8n4p23 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v8n4p23 Abstract Traditional attiéké and commercial attiéké Garba are fermented cassava semolina, steamed and prized by people living in the big cities of Côte d'Ivoire and elsewhere. Attiéké Garba is a derivative of the traditional attiéké resulting from intended manufacturing defects. A consumption survey was therefore conducted in Abidjan (big city) and two departments, Dabou and Jacqueville, major production areas of attiéké and Garba, to assess the importance and determinants of consumption of 4 types of attiéké (Adjoukrou, Ebrié, Alladjan and Garba), consumer preferences and to identify the descriptors of quality that motivate the consumption of these food products. Surveys showed that 99% of respondents consume regularly 1 to 2 times attiéké (traditional or commercial) per day. -

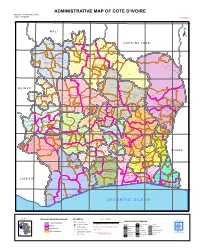

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Licence Iii Tronc Commun 2019-2020

UFHB 2019-2020 LICENCE III TRONC COMMUN 2019-2020 Nº NOMS PRENOMS DATE LIEU Nº CE SEXE GROUPES 1 ABALE JEAN MARC DENIS 1996-05-08 YERIKO(LAKOTA) CI0117327469 M 1 2 ABE ASSI LOYA CHADON JAC 1999-12-14 MARCORY CI0118338174 F 2 3 ABOLI ASSANDE DANIEL 2000-12-28 BENENE CI0118338070 M 3 4 ABOU ABOU LANDRY 1995-01-01 N'KOUPE/ADZOPE CI0118351110 M 4 5 ABOUA EFFIBE GENEVIEVE 1992-06-10 BONOUA F 15 6 ABOULE MELISSA CARMEN JENNIFER 1999-05-14 YOPOUGON CI0118337945 F 5 7 ACHIA LOBA AGRE LAUTRECE C 0000-00-00 N'GOKRO CI0117333768 M 6 8 ADAMA OUATTARA 0000-00-00 LELEBLE/TAABO CI0116323182 M 7 9 ADAYE KOUADIO SOULEYMANE 1998-12-27 AHUITIESSO CI0117321567 M 8 10 ADECHIAN OLOUWAFEMI ADEBAYO EMMANUEL 1997-03-06 ABOBO CI0118338128 M 9 11 ADEDOYIN ISMAEL 1999-03-18 OUANGUIE / AGBOVILLE CI0118337865 M 10 12 ADEKUNLE RASHEED ABDOUL MALICK 1998-11-10 ABOBO CI0118338077 M 11 13 ADINGRA YAO BENE MOISE 1999-08-20 LOMO CI0118337835 M 12 14 ADJE AMLAN CLARISSE 1996-03-02 ADAOU CI0117325330 F 13 15 ADOU YAO TAWA ROMARIC 1996-01-03 TABAGNE CI0115297550 M 14 16 ADOU AKPANE VERONIQUE 1996-12-29 COSROU/DABOU CI0117324816 2 17 ADOU AYO JOSEPH FABIEN 1993-08-03 BECEDI CI0113258768 M 1 18 ADOUA KOBENAN SALOMON 1998-10-01 BONDOUKOU CI0118337986 M 2 19 ADOUM KOUASSI KONANDOU EMMANUEL 1997-06-29 YOPOUGON CI0117356700 M 3 20 AFFALI ASSI THANO PIERRE 1998-06-17 ABOISSO CI0117327522 M 4 21 AGO KONAN ELIE 1995-12-15 OBROUAYO/SOUBRE/RCI CI0118354974 M 5 22 AGOSSOU FRANCK-VISSOU 1997-06-02 ANYAMA CI0118337831 M 6 23 AHETCHEY KONAN DELAURE ETRANN 1996-05-10 YAMOUSSOUKRO CI0117348903 -

Grands Ponts

RÉPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE Union – Discipline – Travail INSTITUT NATIONAL DE RECENSEMENT GÉNÉRAL DE LA STATISTIQUE (INS-SODE) LA POPULATION ET DE L’HABITAT RGPH) 2014 ( Répertoire des localités RÉGION DES GRANDS-PONTS ©INS, JUIN 2015 Table des matières AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................................................................................................. 3 PRÉSENTATION ................................................................................................................................................... 4 DÉPARTEMENT DE DABOU .............................................................................................................................. 8 SOUS-PRÉFECTURE DE DABOU .................................................................................................................. 11 SOUS-PRÉFECTURE DE LOPOU ................................................................................................................... 12 SOUS-PRÉFECTURE DE TOUPAH ............................................................................................................... 13 DÉPARTEMENT DE GRAND-LAHOU ............................................................................................................ 14 SOUS-PRÉFECTURE D’AHOUANOU .......................................................................................................... 17 SOUS-PRÉFECTURE DE BACANDA ........................................................................................................... -

Some Aspects of the Epidemiology of African Cassava Mosaic Virus in Ivory Coast

I r-1 j. _. TROPICAL PEST MANAGEMENT 1988 34flI 92-96 h:cIyfImi:'ms__- - 5cn,-- 'll'll. .- , - 'h . IS 5 - t" Some aspects of the epiaemiology of African cassava mosaic virus in Ivory Coast l (Keywords: Cassava. vws. whitefly, ACMV, epidemiology. Africa) 0 I ARGETTE, and L. C. HOUVENEL Laboratoire dP Virolope Vegetale. Institut1 Francars de Recherche Scientifique pour le Developpement en Cooperation P. (ORSTOM) B. V51. Abidjan, Ivory Coast Abstract. Re-infection of healthy cassava plants by African cassava epidemiological features and the overall ecology of ACMV in mosaic virus (ACMV) was followed in different varieties and tor different situations: several years at various locations in two regions of Ivory Coast. Whitefly populations on cassava and virus incidence varied widely between sites. even amongst those close to one another. However, for each location and in every year. the spread of ACMV showed the same general trend Little spread occurred at Toumodi ín the Savannah region which IS outside the main cassava production area. Much greater spread occurred at a nearby site and at all sites in the forest region except one alongside the Ocean where there were no cassava plantings upwind. Among sites there was no direct relation between virus incidence and the total number of adult whitefly, whereas there was a relationship between spread and the occuir- ence of .nfected cassava upwind although not necessarily close by. Introduction African cassava mosaic disease is one of the most important factors limiting the production of cassava (Manihot esculenla Crantz) in Africa. The disease is caused by a gentnivirus (ACMV), which aflects nearly all the cassava plants grown. -

Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics Of

International Journal of Nutritional Science and Food Technology Volume 4 Issue 8, November 2018 International Journal of Nutritional Science and Food Technology Research Article ISSN 2471-7371 Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of cassava starters used for the production of the main types of attiéké in Côte d’Ivoire Kouassi Kouadio Benal*1,2, Kouassi Kouakou Nestor1, Nindjin Charlemagne1,2 and Amani N’Guessan Georges1 1Food Biochemistry and Technologies Department, Université Nangui Abrogoua, 02 BP 801 Abidjan 02, Côte d’Ivoire 2Food Security Research Group, Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), 01 BP 1303 Abidjan 01, Côte d’Ivoire Abstract Five types of attiéké have been described in Côte d’Ivoire according to their origin of production. The type of starter added into cassava dough is one main determinant of attiéké quality therefore the physicochemical and microbial profiles of 30 cassava starters from the main production zones in Côte d’Ivoire were determined in this study. Starters produced in Dabou, Jacqueville and Grand-Lahou were more acidic. Their total acidities were respectively 9.25 ± 2.46 g l-1, 6.75 ± 2.11 g l-1 and 6.89 ± 1.99 g l-1 with low pH (4.53 ± 1.18, 4.42 ± 0.35 and 4.68 ± 0.26). Those from Abidjan and Yamoussoukro were less acidic with lower total acidities (5.52 ± 1.97 g l-1 and 4.82 ± 1.37 g l-1) and higher pH (4.95 ± 0.33 and 5.45 ± 0.49). Moisture levels of samples from Dabou, Jacqueville and Grand-Lahou were lower, while their reducing sugar and starch content were higher compared with those from Abidjan and Yamoussoukro. -

Anthropologie Des Enjeux De La Violence Chez Lagunaires De Côte D’Ivoire

78 AFRICAN SOCIologICAL REVIew Anthropologie des enjeux de la violence chez lagunaires de Côte d’Ivoire Mel Meledje Raymond Université de Bouaké – Département d’Anthropologie et de Sociologie 08 B.P. 1033 ABIDJAN 08 Email: [email protected] Résumé Le projet d’une Côte d’Ivoire nouvelle suscite particulièrement dans les communautés lagunaires une dynamique de transformation des ordres sociaux (institutions, idéologie des classes d’âge, matrilinéarité) face aux nouveaux enjeux qui mobilisent les populations (démocratie, développement, bien-être des populations, respect des institutions, création de nouvelles richesses, etc.). L’analyse socio-anthropologique de la micro-violence dans ces communautés à travers ces ordres sociaux et leur transformation, la justification des indices d’expression de la violence et les enjeux de celle-ci dans la transformation sociale, révèle que la violence en «s’inscrivant » dans ce processus comme un désordre apparent (Gbudzu-gbudzu), mieux comme un moyen de passage de l’ordre ancien à l’ordre nouveau, est au surplus le thermostat dans la bonne marche de la transformation sociale pour un mieux être. Mots-clés: Micro-violence, matrilinéarité, classes d’âge, développement, conflit, désordre, transformation, Introduction Dans la littérature des sciences sociales relatives à la Côte d’Ivoire, depuis la crise sociopolitique qui a débuté en 1999, l’on constate un intérêt croissant pour la macro violence (Akindès 1990; Akindès 2003; Akindès 2004; Konaté 2004; Bouquet 2005; Langer 2005; Collett 2006; Marshall-Fratani 2006). Mais, pour comprendre les dynamiques de la macro-violence, l’on ne peut minorer l’importance des micro-violences, c’est-à-dire des expressions de violence socialement et/ou géographiquement circonscrites. -

Sedimentological Characterization of Subsurface Formations of the Tertiary - Quaternary in the Dabou Region (South of Ivory Coast)

International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS) ISSN: 2394-3661, Volume-5, Issue-10, October 2018 Sedimentological Characterization Of Subsurface Formations Of The Tertiary - Quaternary In The Dabou Region (South Of Ivory Coast) Gbangbot Jean-Michel Kouadio, N'Doufou Gnosseith Huberson Claver, Saimon Aby Atsé Mathurin basin is also known from the work of [3] - [4] - [5] - [6] - [7] - Abstract— About 239 samples of cuttings from two boreholes [1] - [8] - [9] - [10], based on outcrops and drill cuttings at located in Dabou were the subject of sedimentological studies Alépé, Bingerville, Samo, Adiaké, Eboinda, Assinie, Adjamé, (lithological, granulometric and morphoscopic analysis) in this work. These studies aim to identify the origin of these sediments Bonoua, Aboisso and Yopougon. The aim of these and to specify the factors and the phenomena which involved in studies was to specify the lithostratigraphic characteristics of their transport and their deposit during Tertiary - Quaternary. the formations encountered, their origin, and the factors and After a detailed lithological description of each sample, the sandy fractions were treated according to conventional particle phenomena involved in sediment transport and size methods. The formations traversed in the two wells consist deposition.The data on this part of the Dabou basin are scarce, of lateritic clays, yellow clays, clay sands and coarse sands. The like some works available in literature, [11] which worked on analyzed sands are coarse and testify to the différents variations the quantitative and qualitative aspect of the groundwater of in the energy of the stream that transported the sediments. The hyperbolic granulometric facies is dominant in the study area, Dabou and [12] which worked on the indicating a variation in streamflow during sedimentation.