Glossary of Sea Turtle Terms 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beach Dynamics and Impact of Armouring on Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys Olivacea) Nesting at Gahirmatha Rookery of Odisha Coast, India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 45(2), February 2016, pp. 233-238 Beach dynamics and impact of armouring on olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast, India Satyaranjan Behera1, 2, Basudev Tripathy3*, K. Sivakumar2, B.C. Choudhury2 1Odisha Biodiversity Board, Regional Plant Resource Centre Campus, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-15 2Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, PO Box 18, Chandrabani, Dehradun – 248 001, India. 3Zoological Survey of India, Prani Vigyan Bhawan, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 (India) *[E. mail:[email protected]] Received 28 March 2014; revised 18 September 2014 Gahirmatha arribada beach are most dynamic and eroding at a faster rate over the years from 2008-09 to 2010-11, especially during the turtles breeding seasons. Impact of armouring cement tetrapod on olive ridley sea turtle nesting beach at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast has also been reported in this study. This study documented the area of nesting beach has reduced from 0.07 km2to 0.06 km2. Due to a constraint of nesting space, turtles were forced to nest in the gap of cement tetrapods adjacent to the arribada beach and get entangled there, resulting into either injury or death. A total of 209 and 24 turtles were reported to be injured and dead due to placement of cement tetrapods in their nesting beach during 2008-09 and 2010-11 respectively. Olive ridley turtles in Odisha are now exposed to many problems other than fishing related casualty and precautionary measures need to be taken by the wildlife and forest authorities to safeguard the Olive ridleys and their nesting habitat at Gahirmatha. -

Kansas 4-H Poultry Leader Notebook Level I Introduction for Leaders

Kansas 4-H Poultry Leader Notebook Level I Introduction for Leaders ........................................................i Parts of a Chicken......................................................................................................3 Name That Bird.......................................................................................................11 Beginning to Set Goals in Your Poultry Project......................................................19 Common Poultry Terms for Different Species........................................................23 Poultry Breeds.........................................................................................................27 Breeds of Poultry for Project and Show..................................................................33 What Bird Will I Raise?..........................................................................................41 Nutritional Needs and Problems in Poultry.............................................................45 Is Your Bird Sick?...................................................................................................51 Catching and Handling Poultry...............................................................................55 Washing That Bird...................................................................................................59 Why Do We Raise Poultry?.....................................................................................63 K-State Research & Extension ■ Manhattan Leader Notes Parts of a Chicken Poultry, -

Green Sea Turtle in the New England Aquarium Has Been in Captivity Since 1970, and Is Believed to Be Around 80 Years Old (NEAQ 2013)

Species Status Assessment Class: Reptilia Family: Cheloniidae Scientific Name: Chelonia mydas Common Name: Green turtle Species synopsis: The green turtle is a marine turtle that was originally described by Linnaeus in 1758 as Testudo mydas. In 1868 Marie Firmin Bocourt named a new species of sea turtle Chelonia agassizii. It was later determined that these represented the same species, and the name became Chelonia mydas. In New York, the green turtle can be found from July – November, with individuals occasionally found cold-stunned in the winter months (Berry et al. 1997, Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles are sighted most frequently in association with sea grass beds off the eastern side of Long Island. They are observed with some regularity in the Peconic Estuary (Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles experienced a drastic decline throughout their range during the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of human exploitation and anthropogenic habitat degradation (NMFS and USFWS 1991). In recent years, some populations, including the Florida nesting population, have been experiencing some signs of increase (NMFS and USFWS 2007). Trends have not been analyzed in New York; a mark-recapture study performed in the state from 1987 – 1992 found that there seemed to be more green turtles at the end of the study period (Berry et al. 1997). However, changes in temperature have lead to an increase in the number of cold stunned green turtles in recent years (NMFS, Riverhead Foundation). Also, this year a record number of nests were observed at nesting beaches in Flordia (Mote Marine Laboratory 2013). 1 I. -

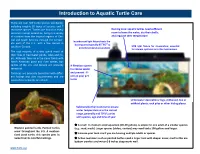

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Indirect Effects of Overfishing on Caribbean Reefs: Sponges Overgrow Reef-Building Corals

Indirect eVects of overfishing on Caribbean reefs: sponges overgrow reef-building corals Tse-Lynn Loh1,∗, Steven E. McMurray1, Timothy P. Henkel2, Jan Vicente3 and Joseph R. Pawlik1 1 Department of Biology and Marine Biology and Center for Marine Science, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, NC, USA 2 Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, GA, USA 3 Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology, University of Maryland Center for Environ- mental Science, Baltimore, MD, USA ∗ Current aYliation: Daniel P. Haerther Center for Conservation and Research, John G. Shedd Aquarium, Chicago, IL, USA ABSTRACT Consumer-mediated indirect eVects at the community level are diYcult to demonstrate empirically. Here, we show an explicit indirect eVect of overfishing on competition between sponges and reef-building corals from surveys of 69 sites across the Caribbean. Leveraging the large-scale, long-term removal of sponge predators, we selected overfished sites where intensive methods, primarily fish-trapping, have been employed for decades or more, and compared them to sites in remote or marine protected areas (MPAs) with variable levels of enforcement. Sponge-eating fishes (angelfishes and parrotfishes) were counted at each site, and the benthos surveyed, with coral colonies scored for interaction with sponges. Overfished sites had >3 fold more overgrowth of corals by sponges, and mean coral contact with sponges was 25.6%, compared with 12.0% at less-fished sites. Greater contact with corals by sponges at overfished sites was mostly by sponge species palatable to sponge preda- tors. Palatable species have faster rates of growth or reproduction than defended sponge species, which instead make metabolically expensive chemical defenses. -

Spirorchiidiasis in Stranded Loggerhead Caretta Caretta and Green Turtles Chelonia Mydas in Florida (USA): Host Pathology and Significance

Vol. 89: 237–259, 2010 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published April 12 doi: 10.3354/dao02195 Dis Aquat Org OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spirorchiidiasis in stranded loggerhead Caretta caretta and green turtles Chelonia mydas in Florida (USA): host pathology and significance Brian A. Stacy1,*, Allen M. Foley2, Ellis Greiner3, Lawrence H. Herbst4, Alan Bolten5, Paul Klein6, Charles A. Manire7, Elliott R. Jacobson1 1University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, PO Box 100136, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 2Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Jacksonville Field Laboratory, 370 Zoo Parkway, Jacksonville, Florida 32221, USA 3University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Diseases and Pathology, PO Box 110880, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 4Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York 10461, USA 5Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida, PO Box 118525, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA 6Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 7Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Florida 34236, USA ABSTRACT: Spirorchiid trematodes are implicated as an important cause of stranding and mortality in sea turtles worldwide. However, the impact of these parasites on sea turtle health is poorly understood due to biases in study populations and limited or missing data for some host species and regions, includ- ing the southeastern United States. We examined necropsy findings and parasitological data from 89 log- gerhead Caretta caretta and 59 green turtles Chelonia mydas that were found dead or moribund (i.e. stranded) in Florida (USA) and evaluated the role of spirorchiidiasis in the cause of death. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

Evolution of Oviductal Gestation in Amphibians MARVALEE H

THE JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL ZOOLOGY 266394-413 (1993) Evolution of Oviductal Gestation in Amphibians MARVALEE H. WAKE Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 ABSTRACT Oviductal retention of developing embryos, with provision for maternal nutrition after yolk is exhausted (viviparity) and maintenance through metamorphosis, has evolved indepen- dently in each of the three living orders of amphibians, the Anura (frogs and toads), the Urodela (salamanders and newts), and the Gymnophiona (caecilians). In anurans and urodeles obligate vivi- parity is very rare (less than 1%of species); a few additional species retain the developing young, but nutrition is yolk-dependent (ovoviviparity) and, at least in salamanders, the young may be born be- fore metamorphosis is complete. However, in caecilians probably the majority of the approximately 170 species are viviparous, and none are ovoviviparous. All of the amphibians that retain their young oviductally practice internal fertilization; the mechanism is cloaca1 apposition in frogs, spermato- phore reception in salamanders, and intromission in caecilians. Internal fertilization is a necessary but not sufficient exaptation (sensu Gould and Vrba: Paleobiology 8:4-15, ’82) for viviparity. The sala- manders and all but one of the frogs that are oviductal developers live at high altitudes and are subject to rigorous climatic variables; hence, it has been suggested that cold might be a “selection pressure” for the evolution of egg retention. However, one frog and all the live-bearing caecilians are tropical low to middle elevation inhabitants, so factors other than cold are implicated in the evolu- tion of live-bearing. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae.