Case of Interfin and Royal Bank)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monetary Policy Statement

Monetary Policy Statement BY DR. G. GONO GOVERNOR RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE January 2011 2011 MonJaenutaray2r0y11 :: Policy Statement ISSUED IN TERMS OF THE RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE ACT CHAPTER 22:15, SECTION 46 By DR. G. GONO GOVERNOR RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE JANUARY 2011 tableof Contents INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 5 GLOBAL REAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS 6 GLOBAL OUTLOOK 8 GLOBAL INFLATION DEVELOPMENTS 9 INTERNATIONAL COMMODITY PRICE DEVELOPMENTS 10 CAPITAL FLOWS 13 ZIMBABWE: REAL SECTOR OVERVIEW 15 AGRICULTURE 15 TOBACCO 16 SUGAR 17 MINING 17 PLATINUM 19 CHROME 19 NICKEL 19 COAL 19 MANUFACTURING 20 TOURISM 20 INFLATION 21 YEAR-ON-YEAR INFLATION 22 MONTH-ON-MONTH INFLATION 23 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND VERSUS UNITED STATES DOLLAR 24 OIL PRICE DEVELOPMENTS 25 MONETARY DEVELOPMENTS 25 DISTRIBUTIONS OF CREDIT TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR 26 MULTINATIONAL BANKS 27 LOANS TO DEPOSITS RATIOS AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2010 27 FINANCIAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS 28 ARCHITECTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 29 tableof Contents STATUS OF BANKING SECTOR CAPITALISATION 30 CAPITALISATION LEVELS OF BANKING INSTITUTIONS 30 LEVEL OF CAPITALISATION OF ASSET MANAGEMENT COMPANIES (AMCS) 31 STATUS OF MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS 31 BANK CHARGES AND DEPOSIT RATES 31 BASE II IMPLEMENTATION 32 FINANCIAL INCLUSION 32 MERGER AND ACQUISITIONS 33 KINGDOM BANK LIMITED 33 INTERFIN BANKING CORPORATION LIMITED 33 PREMIER BANKING CORPORATION 33 EXTERNAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS 34 EXTERNAL DEBT DEVELOPMENTS 35 SHORT-TERM TRADE FINANCE FACILITIES 35 EXCHANGE CONTROL 37 EXPORT PERFORMANCE FOR THE YEAR 2010 38 EXPORT PERFORMANCE -

13-1-2006. Chairman, Competition Andtariffcommission

Published by Authority Vol. LXXXIV, No. 3 13th JANUARY,2006 Price $45 000,00: GeneralNotice 4 of 2006. Furtherinformation can be obtained during normal business hours STATE PROCUREMENT BOARD from the Commission’s Directorat telephone (04) 775040/5, fac- simile (04) 770175 or by e-mail from [email protected]. Tenders Invited O. M. TSHABANGU, Tenders must be enclosed in sealed envelopes, endorsed on the outside with the 13-1-2006. Chairman, Competition and Tariff Commission. advertised tender number, description, closing date and mustbe posted in time to be sorted into Post Office Box Number CY 408, Causewayor delivered by hand to the General Notice 6 of 2006. Principal Officer, State Procurement Board,Fifth Floor, Old Reserve Bank Building, 76, Samora Machel Avenue, Harare, before 10.00 a.m. on the closing date. PREVENTION OF CORRUPTION ACT [CHAPTER9:16] E. M. USHEWOKUNZE, 13-1-2006. Principal Officer, State Procurement Board. Declaration of Specified Persons and Appointmentof Investigator Tender number CON.66/2005. Harare. Construction of road works at Morgan THE Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, in ZINTEC College. Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Educa- terms of section 6(1) of the Prevention of Corruption Act tion. Compulsory site visit will be held at Morgan ZINTEC {Chapter 9:16], hereby declares the personslisted in the Schedule College, corner Alamein Road and J. M. Nkomo Road, to be specified persons, and furtherin termsof section 7 of the said Act appoints and assigns Mr. Reggie Francis Saruchera of Messrs Braeside, Harare, on 26th January, 2006, at 10.00 a.m. -

Myclassifieds 12 December 2014 Listings

To advertise in print or online contact To adverMyClassifiedstise in print Toream online NewsDay contact MyClassifieds 12 December 2014 ListingsMyClassifiedsTel: 04-773930-9, Team NewsDay Email: [email protected] MyClassifiedsSearchSearch Find Find Buy Buy Sell Sell Tel: 04-773930-9, Email: [email protected] Property Vehicles Jobs For Sale Business Houses For Sale Buses Banking/Accounting/Finance/ Cell Phones - Accessories Banking & Insurance Houses Wanted Trucks & Commercial Vehicles Insurance Clothing Building & Hardware Sales/Marketing/Advertising/ Accomodation Available Vehicles For Sale Domestic Appliances Education Houses To Let Public Relations Sound & Vision Property Vehicle Spares & Accessories Administrative/Secretarial/ Flats For Sale Clerical Electronics Hotels & Lodges Flats To Let Human Resource Home - Furniture - Garden Information Communication & Plots/Properties For Sale Business / Strategic Technology Business Premises Available Management Motor Vehicles & Accessories Business Premises Wanted Legal Retail Clothing/Security OVER A DECADE OF EXPERIENCE IN THE WATER INDUSTRY!!! CYPRUS INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY (+90) 392 671 11 11 Ext:2074 (+90) 392 671 11 30 Haspolat - Nicosia, North Cyprus via MERSİN 10 TURKEY ON SPOT ADMISSION AND SEMINARS IN ZIMBABWE Meet Ms. Hazal ARIPINAR, Head of Admissions, CIU International Office BULAWAYO SEMINAR HARARE SEMINAR 18005 Dhlela Way, Graniteside. Harare Tel: +263 (4) 748118, 748 120 AUCTIONEERS Email: [email protected] 3 December 2014 , 10am – 5pm 5 December 2014 -

School of Postgraduate Studies Bank Failures: Examining Corporate Governance Principles and Practices of Indigenous Banks in Zi

SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES BANK FAILURES: EXAMINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES OF INDIGENOUS BANKS IN ZIMBABWE AND THEIR IMPACT ON ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS BY JUSTINE CHINOPEREKWEYI PHDOLD1511443 SUPERVISORS: DR. EMMANUEL P. MULENGA DR. ABEL C. SHIMBA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the Doctor of Philosophy Degree (PhD) in Organizational Leadership and Development at the University of Lusaka, Zambia. 2018 P a g e | i Abstract The health of the banking industry is strongly dependent on the state of corporate governance in an economy. The adoption and enthronement of sound corporate governance principles and practices is regarded as important in ensuring bank organizational effectiveness at institutional, industry and inclusive levels. The inclusive level of organizational effectiveness takes into consideration all the stakeholders of the bank. The Zimbabwean economy has experienced persistent indigenous bank failures allegedly due to internal corporate governance deficiencies during the period 2000-2015. The present study sets out to address two research concerns (1) to identify and discover Zimbabwean indigenous banks’ corporate governance irrationalities with regard to organizational effectiveness and, (2) to achieve regulation change through understanding and explaining the impacts of the adopted corporate governance principles and practices on organizational effectiveness. This research examines the corporate governance mechanisms of Zimbabwean indigenous banks and their impact on organizational effectiveness. The research adopts a methodological pluralism approach using the phenomenology and symbolic interactionism epistemological strands. These techniques are used in an effort to address the cardinal points of this research being to identify, discover, understand, explain, predict and recommend controls to the bank failures in light of internal corporate governance deficiencies phenomenon in Zimbabwe. -

Financial Regulation and Supervision in Zimbabwe: an Evaluation of Adequacy and Options

Financial Regulation and Supervision in Zimbabwe: An Evaluation of Adequacy and Options John D. G. Nhavira Evengelista Mudzonga Everisto Mugocha Financial Regulation and Supervision in Zimbabwe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ZEPARU acknowledges the financial support provided by the Government of Zimbabwe, African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF) and USAID Strategic Economic Research and Analysis—Zimbabwe (SERA) Program under contract number USAID-613-C-11-00001, without which this study would not have been possible. This study is part of a broader set of studies on the financial sector development in Zimbabwe commissioned by ZEPARU. The Study team acknowledges the inputs from diverse stakeholders and colleagues who shared their insights and spared time to provide information and data that was used in this study. Special thanks go to Professor Daniel Makina, Dr. Gibson Chigumira and Dr. Sehliselo Mpofu who reviewed the draft paper during the research process. Comments from Mr. A Ncube of MEFMI and participants of the financial sector studies dessemination workshop held on the 26th of July 2013 at Pandhari Lodge, Harare Zimbabwe are greatly appreciated. The findings of this study do not necessarily reflect the views of ZEPARU or its funding partners. The authors bear full responsibility for any factual errors and omissions. ii An Evaluation of Adequacy and Options TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................................................................................ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... -

2010 Annual Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS D P d e D r p a o B o sit B Protection DEPOSIT PROTECTION BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2010 1 CORPORATE VISION, MISSION AND VALUES D P d e D r p a o B o sit B Protection CORPORATE VISION, MISSION AND VALUES Corporate Vision To be Africa's Centre of Excellence in deposit protection. Mission Statement To protect deposits, enhance public confidence and stability in the financial system. Our Values To achieve the above, the DPB is guided by the following core values. • Accountability - We take full ownership and responsibility for our actions. We account to our stakeholders and are compliant. We adhere to sound corporate governance principles and are disciplined in thought and conduct. • Fairness - We fairly implement our mandates and treat all our stakeholders with equity. We create a level playing field that allows every stakeholder to contribute to economic development. • Innovation - We choose to make a difference with our knowledge and ideas. We benchmark ourselves with world-class players and continually improve our systems, processes and practices. We build capacity to deliver and tap the full potential of every team player. We embrace new ideas. liberate thought, talent and creativity. • Teaming - We are cooperative. We are open to different views and we value diversity. We listen and share ideas. We recognize and work with partners to accomplish our goals. We continually raise our interpersonal skills and positively interact to deliver breakthrough results. We value and engage our stakeholders and publics. • Integrity - We hold ourselves up to the highest ethical and professional standards. -

Ijcrb.Webs.Com 467 Non Performing Loans in Commercial Banks: a Case of CBZ Bank Limited in Zimbabwe

ijcrb.webs.com NOVEMBER 2012 INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH IN BUSINESS VOL 4, NO 7 Non Performing loans in Commercial Banks: A case of CBZ Bank Limited In Zimbabwe Mabvure Tendai Joseph1, Gwangwava Edson2, Faitira Manuere3, Mutibvu Clifford4, Kamoyo Michael5 1,2Lecturers: Department of Accounting Science and Finance Chinhoyi University of Technology P.Bag 7724 Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe 3Lecturer :Department of Business Management and Entprepreneurship Chinhoyi University of Technology P.Bag 7724 Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe 4 Manager :E-Banking and Card Services CBZ Bank limited 5Michael Kamoyo, Lecturer: Department of International Marketing Chinhoyi University of Technology P.Bag 7724 Chinhoyi Zimbabwe Corresponding Author Mabvure Tendai Joseph Abstract The purpose of the study was to find out the causes of non-performing loans in Zimbabwe. Loans form a greater portion of the total assets in banks. These assets generate huge interest income for banks which to a large extent determines the financial performance of banks. However, some of these loans usually fall into non-performing status and adversely affect the performance of banks. In view of the critical role banks play in an economy, it is essential to identify problems that affect the performance of these institutions. This is because non-performing loans can affect the ability of banks to play their role in the development of the economy. A case study research design of CBZ Bank Limited was employed. Interviews and questionnaires were used to collect data for the study. The paper revealed that external factors are more prevalent in causing non performing loans in CBZ Bank Limited. The major factors causing non performing loans were natural disasters, government policy and the integrity of the borrower. -

Weekly African Footprint

For week ending 13 April 2012 Weekly African Footprint We have included summaries for the countries listed below, please click on the country name should you wish to navigate to it directly: Botswana Morocco Egypt Namibia Ghana Nigeria Kenya Tanzania Malawi Zambia Mauritius Zimbabwe African Stock Exchange Performance: Currencies: Source:oanda.com Securities Africa Botswana Botswana Stock Exchange Stock Exchange News 9,000.00 The DCI gained a marginal +0.24% to close at 7,075.78 points. Turnstar 8,500.00 8,000.00 and NAP led the gainers after adding +7.14% and +4.65% to close at BWP 7,500.00 7,000.00 1.50 and BWP 2.25 respectively. Other counters to gain included Letlole 6,500.00 6,000.00 (+4.55%), New Gold (+.65%) and Stanchart (+0.33%). On the losing front we 1/31/2008 2/29/2008 3/31/2008 4/30/2008 5/31/2008 6/30/2008 7/31/2008 8/31/2008 9/30/2008 1/31/2009 2/28/2009 3/31/2009 4/30/2009 5/31/2009 6/30/2009 7/31/2009 8/31/2009 9/30/2009 1/31/2010 2/28/2010 3/31/2010 12/31/2007 10/31/2008 11/30/2008 12/31/2008 10/31/2009 11/30/2009 12/31/2009 had Cresta (-5.45%) to BWP 1.04, Selafana (-1.79%) and RDCP (-0.73%). Source: Reuters Corporate News BWP/USD TSX-V-quoted Galane Gold has completed the acquisition of Northern 9 Lights Exploration (NLE), giving it control over prospective gold areas in 8.5 the Tati Greenstone Belt, in Botswana. -

IV. TRADE POLICIES and PRACTICES by SECTOR (1) 1. Zimbabwe Considers Agriculture

WT/TPR/S/252/Rev.1 Trade Policy Review Page 62 IV. TRADE POLICIES AND PRACTICES BY SECTOR (1) INTRODUCTION 1. Zimbabwe considers agriculture (including livestock and forestry) as one of the engines of economic growth necessary for its reconstruction and poverty reduction. Since 2000, the sector has faced constant decline in both production and productivity, mainly due to, inter alia, the Fast Track Land Reform Programme, erratic weather, limited access to finance (local and offshore), energy (electricity and fuel) problems, infrastructure bottlenecks, producer and food price controls, and large- scale underutilization of land. Lack of security of tenure has negatively affected investment in the sector. The Government intends to revive all the agriculture subsectors including maize, wheat, tobacco, cotton, coffee, sugar, beef, horticulture, and floriculture. Agricultural activities remain heavily protected and supported, including through high tariffs, a price band system, and other government incentives such as export finance, insurance, guarantees and other related trade finances facilities. 2. Mining has been a preferred sector for foreign investment in Zimbabwe; it has an immense potential. The policy objectives are, inter alia, to sustain development of the country's mineral resources and to create employment opportunities by profitably exploiting Zimbabwe's natural resources for its socio-economic development. Environmental issues in mineral exploitation, as well as indigenization and empowerment issues, are given due attention at project inception and development stages. The mining sector continues to benefit from incentives provided under the different trade and investment regimes. However, increasing government control, and lack of clarity over the mining royalty and tax regimes remain. -

2006 Annual Report 2006 Annual Bank Licensing, Supervision Bank Licensing

bank licensing, supervision and surveilLance report 2006 report and surveilLance supervision bank licensing, bank licensing, supervision & surveilLance 2006 Annual Report DS MARKETING PO BOX EH149 EMERALD HILL, HARARE, PHONE 011 606 171 DS MARKETING PO BOX EH149 EMERALD HILL, HARARE, PHONE 011 Copies of the Annual Report are available from: Senior Division Chief Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe Bank Licensing, Supervision & Surveillance Division 80 Samora Machel Avenue Harare Zimbabwe Fax: +263-4-705928 Tel: +263-4-703000 Also available on the Reserve Bank website (www.rbz.co.zw) BANK LICENSING, SUPERVISION & SURVEILLANCE ANNUAL REPORT 2006 CONTENTS PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 DEPUTY GOVERNOR’S REMARKS............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 SENIOR DIVISION CHIEF’S PREVIEW ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................8 -

26Th MAY, 2006 Price $195 000,00

7M Published by Authority Vol. LXXXIV, No. 35. 26th MAY, 2006 Price $195 000,00 General Notice 129 of 2006. General Notice 131 of 2006. : . - THE following Bill is published with this Gazette for general BANKING ACT [CHAPTER 24:20] information— ; . Interception of Communications Bill, 2006 (H.B. 4 of 2006). Approval of Merger of CFX Bank Limited and CFX Merchant Bank Limited A.M. ZVOMA, 26-5-2006. Clerk of Parliament. * IT is hereby notified that, in terms of section 25(6) of the Banking Act {Chapter 24:20], the Minister ofFinance has,in terms of section, General Notice 130 of 2006. 25(5) of the said Act, approved the merger ofCFX Bank Limited and CFX Merchant Bank Limited. Thenameofthe merged entity is CFX STATE PROCUREMENT BOARD Bank Limited. Tenders Invited H. MURERWA, 26-5-2006. - Minister of Finance. Tenders must be enclosed in sealed envelopes, endorsed on the outside with the advertised tender number,description, closing date and must be posted in time to be . General Notice 132 of 2006. Sorted into Post Office Box Number CY 408, Causeway or delivered by hand to the Principal Officer, State Procurement Board, Fifth Floor, Old Reserve Bank Building, LABOUR ACT (CHAPTER 28:01] 76, Samora Machel Avenue, Harare, before 10.00 a.m. on the closing date. : E. M. USHEWOKUNZE, Notice of Accreditation Proceedings: Zimbabwe Funeral Service 26-5-2006. Principal Officer, State Procurement Board, : and Assurance Employers Association Boe ipie aaety ~ changed the mili. / IT is hereby notified that, in terms of section 42 of the Labour Act ZOU/FT/01/06. -

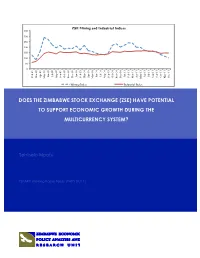

Does the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (Zse) Have Potential to Support Economic Growth During the Multicurrency System?

DOES THE ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE (ZSE) HAVE POTENTIAL POTENTIAL HAVE (ZSE) EXCHANGE STOCK ZIMBABWE THE DOES ZEPARUWorking (ZWPSPaper Series 01/11) Mpofu Sehliselo 100 150 200 250 300 350 50 0 Feb-09 Mar-09 TOSUPPORT ECONOMIC GROWTH DURING THE Apr-09 May-09 Jun-09 Jul-09 Aug-09 Sep-09 MULTICURRENCY SYSTEM? MULTICURRENCY Oct-09 Nov-09 Mining Index Mining Index Dec-09 ZSE and Mining Industrial Indices Jan-10 Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 Aug-10 Sep-10 Oct-10 Nov-10 Dec-10 Industrial Index Industrial Jan-11 Feb-11 Mar-11 Apr-11 May-11 Jun-11 Jul-11 Aug-11 Sep-11 Oct-11 Nov-11 Dec-11 DOES THE ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE (ZSE) HAVE POTENTIAL TO SUPPORT ECONOMIC GROWTH DURING THE MULTICURRENCY SYSTEM? By Sehliselo Mpofu Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit (ZEPARU) 55 Mull Road, Belvedere, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: +263-4-778423 Fax: +263-4-778415 Website: www.zeparu.co.zw E-mail: [email protected] ZEPARU Working Paper Series (ZWPS 01/11) Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................