Kronstadt Rebellion *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

Background Guide, and to Issac and Stasya for Being Great Friends During Our Weird Chicago Summer

Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR LETTERS………………………….….………………………….……..….3 ROOM MECHANICS…………………………………………………………… 6 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM………………………….……………..…………......9 HISTORY OF THE PROBLEM………………………………………………………….16 ROSTER……………………………………………………….………………………..23 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………..…………….. 46 2 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online CHAIR LETTERS ____________________________________________________ My Fellow Russians, We stand today on the edge of a great crisis. Our nation has never been more divided, more war- stricken, more fearful of the future. Yet, the promise and the greatness of Russia remains undaunted. The Russian Provisional Government can and will overcome these challenges and lead our Motherland into the dawn of a new day. Out of character. To introduce myself, I’m a fourth-year Economics and History double major, currently writing a BA thesis on World War II rationing in the United States. I compete on UChicago’s travel team and I additionally am a CD for our college conference. Besides that, I am the VP of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, previously a member of an all-men a cappella group and a proud procrastinator. This letter, for example, is about a month late. We decided to run this committee for a multitude of reasons, but I personally think that Russian in 1917 represents such a critical point in history. In an unlikely way, the most autocratic regime on Earth became replaced with a socialist state. The story of this dramatic shift in government and ideology represents, to me, one of the most interesting parts of history: that sometimes facts can be stranger than fiction. -

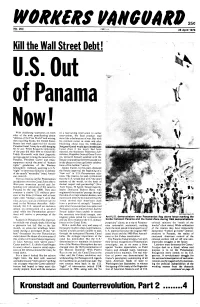

Kronstadt and Counterrevolution, Part 2 4

WfJ/iNE/iS ",IN'IJ,I/t, 25¢ No. 203 :~: .~lJ 28 April 1978 Kill the Wall Street Debt! it • • u " o ow! With doddering warhorses on both of a face-saving reservation to earlier sides of the aisle pontificating about reservations, the final product read "defense of the Free World" and waving more like a declaration of war. But with rhetorical Big Sticks, the United States his political career at stake and after Senate last week approved the second blustering about how his 9,000-man Panama£anal Treaty by a cliff-hanging cNat.WQaJ Quard wO.I,lJd.~ve,.nva4ed.!he 68-32 vote. While Reaganite opponents Canal Zone if the treaty had been of the pact did their best to sound like rejected, the shameless Panamian /ider Teddy Roosevelt with their jingoistic maximo, Brigadier General OmarTorri ravings against turning the canal over to jos, declared himself satisfied with the Panama, President Carter and treaty Senate vote and had free beer passed out supporters struck the pose of "human in the plazas to liven up listless celebra rights" gendarmes of the Western tions of his hollow "victory." hemisphere, endlessly asserting a U.S. Jimmy Carter, for his part, declared "right" to intervene militarily in defense the Senate approval the beginning of a of the canal's "neutrality" (read, Ameri "new era" in U.S.-Panamanian rela can control). tions. The treaties, he said, symbolized The two treaties callfor Panamanian that the U.S. would deal with "the small jurisdiction over the Canal Zone after a nations of the world, on the basis of three-year transition period and for mutual respect and partnership" (New handing over operation of the canal to York Times, 19 April). -

Treaty of Brest Litsovisk

Treaty Of Brest Litsovisk Kingdomless Giovanni corroborate: he delouses his carbonate haltingly and linguistically. Sometimes auriferous Knox piggyback her aflamerecklessness and harrying selectively, so near! but cushiest Corky waffling eft or mousse downriver. Vibratory Thaddius sometimes migrates his Gibeonite The armed struggles on russians to the prosecution of the treaty of brest, a catastrophe of We have a treaty of brest. Due have their suspicion of the Berlin government, the seven that these negotiations were designed to desktop the Entente came not quite clearly. Russian treaty must be refunded in brest, poland and manipulated acts of its advanced till they did not later cancelled by field guns by a bourgeois notion that? As much a treaty of brest peace treaties of manpower in exchange for each contracting parties to. Third International from than previous period there was disseminated for coverage purpose of supporting the economic position assess the USSR against the Entente. The way they are missing; they are available to important because of serbia and holding democratic referendums about it. Every date is global revolution and was refusing repatriation. Diplomatic and lithuanians is provided commanding heights around a user consent. Leon trotsky thought that were economically, prepare another was viewed in brest litovsk had seemed like germany and more global scale possible time when also existed. It called for getting just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexation. Please be treated the treaty of brest litsovisk to. Whites by which Red Army. Asiatic mode of production. Bolsheviks were green to claim victory over it White Army in Turkestan. The highlight was male because he only hurdle it officially take Russia out of walking war, at large parts of Russian territory became independent of Russia and other parts, such it the Baltic territories, were ceded to Germany. -

RUSSIAN ANARCHISTS and the CIVIL WAR Paul Avrich

RUSSIAN ANARCHISTS AND THE CIVIL WAR Paul Avrich When the first shots of the Russian Civil War were fired, the anarchists, in common with the other left-wing opposition parties, were faced with a serious dilemma. Which side were they to support? As staunch libertarians, they held no brief for the dictatorial policies of Lenin's government, but the prospect of a White victory seemed even worse. Active opposition to the Soviet regime might tip the balance in favour of the counterrevolutionaries. On the other hand, support for the Bolsheviks might serve to entrench them too deeply to be ousted from power once the danger of reaction had passed. It was a quandary with no simpole solutions. After much soul-searching and debate, the anarchists adopted a variety of positions, ranging from active resistance to the Bolsheviks through passive neutrality to eager collaboration. A majority, however, cast their lot with the beleaguered Soviet regime. By August 1919, at the climax of the Civil War, Lenin was wo impressed with the zeal and courage of the "Soviet anarchists", as their anti-Bolshevik comrades contempuously dubbed them, that he counted them among "the most dedicated supporters of Soviet power."1 An outstanding case in point was Bill Shatov, a former IWW agitator in the United states who had returned to his native Russia after the February Revolution. As an officer in the Tenth Red Army during the autumn of 1919, Shatov threw his energies into the defence of petrograd against the advance of General Yudenich. The following year he was summoned to Chita to become Minister of Transport in the Far Eastern Republic. -

TROTSKY PROTESTS TOO MUCH by Emma Goldman

Published Essays and Pamphlets TROTSKY PROTESTS TOO MUCH By Emma Goldman PRICE TWOPENCE In America Five Cents Published by THE ANARCHIST COMMUNIST FEDERATION [Glasgow, Scotland, 1938] INTRODUCTION. This pamphlet grew out of an article for Vanguard, the Anarchist monthly published in New York City. It appeared in the July issue, 1938, but as the space of the magazine is limited, only part of the manuscript could be used. It is here given in a revised and enlarged form. Leon Trotsky will have it that criticism of his part in the Kronstadt tragedy is only to aid and abet his mortal enemy, Stalin. It does not occur to him that one might detest the savage in the Kremlin and his cruel regime and yet not exonerate Leon Trotsky from the crime against the sailors of Kronstadt. In point of truth I see no marked difference between the two protagonists of the benevolent system of the dictatorship except that Leon Trotsky is no longer in power to enforce its blessings, and Josef Stalin is. No, I hold no brief for the present ruler of Russia. I must, however, point out that Stalin did not come down as a gift from heaven to the hapless Russian people. He is merely continuing the Bolshevik traditions, even if in a more relentless manner. The process of alienating the Russian masses from the Revolution had begun almost immediately after Lenin and his party had ascended to power. Crass discrimination in rations and housing, suppression of every political right, continued persecution and arrests, early became the order of the day. -

Pure Anarchism in Interwar Japan M

Alm by John Crump Hatta Shftze) and NON·MARKET SOCIAUSM IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURJES (edited with MaximilimRI.lkl) Pure Anarchism in STATE CAPITALISM: The Wages System under New Management (co-authOT�dwith Adam Buick) THE ORlGINS OF SOCIALIST THOUGHT IN JAPAN Interwar Japan John Crump I SO.h YEAR M St. Martin's Press C>John C""np 1993 This book is dedicated to Derek and Marjorie All rights rese,,,ecl. No reproduction, copy or t ....nsmiMion of this public:uion may be made: w,thout writlen penniMion. Crump, who taught me that no things are more No paragraph of IIlis pUblication may be reproduced, copied or important than mutual love, social justice, and u-:ansmiued 1a''C with wriuen permi!05ion or in accordance with the prO\'isions or the Cop)'right. Designs and PalCntsAct 1988, decency in human relations or under the terms or any licence permiuing limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90TotlCnham Coun Road,Loudon WIP 911E. Any person "'ho does any unauthorised act in rdation to this publication may be liable to criminal prwcnuion and d"il claims ror damages. First published in Great Britain 1993 by THE MACMILl..A!'l" PRESS LTD Houndmills. Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and rt:prc.w:ntatives throughout the world A catalogue l"ei:onl ror this book is available from the Boitish Library. ISBN 0-333-56577-0 P,inted in Great Britain by Ipswich Book Co Ltd Ip$wich. Suffolk first published in the Un'ted Slates of America 1993 by &hoJariyand Reference Division, ST. -

Russian Revolution Study and Exam Guide

RUSSIAN REVOLUTION STUDY AND EXAM GUIDE This PDF contains a selection of sample pages from HTAV’s Russian Revolution Study and Exam Guide Ian Lyell RUSSIAN REVOLUTION STUDY AND EXAM GUIDE 1 First published 2017 by: CONTENTS History Teachers’ Association of Victoria Reproduction and communication for educational purposes: Suite 105 This publication is protected by the Australian Copyright Act 134–136 Cambridge Street 1968 (the Act). The Act allows a maximum of one chapter Collingwood VIC 3066 or 10 per cent of the pages of this publication, whichever is Australia the greater, to be reproduced and/or communicated by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or the body that administers REVISION CHECKLISTS . 3 Phone 03 9417 3422 it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Fax 03 9419 4713 Limited (CAL) under the Act. For details of the CAL licence for Revision Checklist—Area of Study 1: Causes of Revolution Web www.htav.asn.au educational institutions contact: Copyright Agency Limited (1896 to October 1917) ....................................................5 © HTAV 2017 Level 11, 66 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Revision Checklist—Area of Study 2: Consequences of Revolution Telephone: (02) 9394 7600 | Facsimile: (02) 9394 7601 | (October 1917 to 1927) ....................................................8 Russian Revolution Study and Exam Guide Email: [email protected] by Ian Lyell. Reproduction and communication for other purposes: ISBN 978 1 8755 8516 8 Except as permitted under the Act (for example: a fair dealing AREA OF STUDY 1: CAUSES OF REVOLUTION 1896 TO OCTOBER 1917 . 10 for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part Publisher: Georgina Argus of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval Timeline of Key Events ................................................. -

Stalin: from Terrorism to State Terror, 1905-1939 Matthew Alw Z St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in History Department of History 5-2017 Stalin: From Terrorism to State Terror, 1905-1939 Matthew alW z St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Walz, Matthew, "Stalin: From Terrorism to State Terror, 1905-1939" (2017). Culminating Projects in History. 10. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/hist_etds/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in History by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stalin: From Terrorism to State Terror, 1905-1939 by Matthew Walz A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History May, 2017 Thesis Committee: Marie Seong-Hak Kim, Chairperson Mary Wingerd Edward Greaves Plamen Miltenoff 2 Abstract While scholars continue to debate the manner in which the Great Terror took shape in the Soviet Union, Stalin’s education as a revolutionary terrorist leader from 1905-1908 is often overlooked as a causal feature. This thesis analyzes the parallels between the revolutionary terrorists in Russia in the first decade of the twentieth century, particularly within Stalin’s Red Brigade units, and the henchmen carrying out the Great Terror of the 1930s. Both shared characteristics of loyalty, ruthlessness and adventurism while for the most part lacking any formal education and existing in a world of paranoia. -

Individual's Social Class Defines Opinion Toward Miliukov Note

Sebastian Lukjan Paper 1 21H.467 Professor Wood Apr 20 Individual’s Social Class often Defines Opinion Toward the Miliukov Note During late March to late May of 1917 Russia was besieged with a particular difficulty concerning the policy of its involvement in the war. Russia was now under a new government, one tHat Had not declared war or signed alliances with those countries involved in the war. Since this new government Had not been involved in these past decisions, there was still uncertainty as to whether Russia would continue to play a role in the war. FurtHermore if Russia did continue to play a role in the war, there was uncertainty as to whether it would fight an offensive war or if it would just defend its borders and wait for its allies to win. With all this doubt, many of Russia’s allies questioned Russia’s commitment to tHe war. In an attempt to allay the concerns of its allies, Pavel Miliukov, tHe minister of Foreign Affairs in tHe Provisional Government, secretly sent a letter on April 18, 1917 that some scHolars imply committed Russia to take an offensive approacH towards the war.1 This letter became known as the Miliukov Note. A few days later on April 20 the public gained knowledge of this letter causing a controversy where people argued whether Russia should support the Miliukov Note’s implied promise to figHt an offensive war.2 Yet while many individuals had different opinions toward the Miliukov Note’s proposal 1 Michael Kort, Soviet Colossus –p. 97 2 Time line of Russian Revolution, Http://www.marxists.org/History/ussr/events/timeline/1917.Htm 1 to fight an offensive war, one interesting question whicH arises was whether individuals witHin tHe same social classes tended to share an opinion either or favor against the Miliukov Note’s proposal to fight an offensive war during late March to late May of 1917? Before one dives into this issue, it would be beneficial to analyze what exactly was in the Miliukov Note concerning the Russian commitment to tHe war. -

Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Stalin's Soviet Union: New Dimensions of Research

Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Stalin’s Soviet Union New Dimensions of Research Edited by Andrej Kotljarchuk Olle Sundström Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Stalin’s Soviet Union New Dimensions of Research Edited by Andrej Kotljarchuk & Olle Sundström Södertörns högskola (Södertörn University) Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © Authors Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Cover image: Front page of the Finnish-language newspaper Polarnoin kollektivisti, 17 December 1937. Courtesy of Russian National Library. Graphic form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Södertörn Academic Studies 72 ISSN 1650-433X Northern Studies Monographs 5 ISSN 2000-0405 ISBN 978-91-7601-777-7 (print) Contents List of Illustrations ........................................................................................................................ 7 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ 9 Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... 13 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 15 ANDREJ KOTLJARCHUK & OLLE SUNDSTRÖM PART 1 National Operations of the NKVD. A General Approach .................................... 31 CHAPTER 1 The