Arbitration Report Issue 02 - 2015 This Issue Includes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES A. BAKER, III the Case for Pragmatic Idealism Is Based on an Optimis- Tic View of Man, Tempered by Our Knowledge of Human Imperfection

Extract from Raising the Bar: The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society, by Talmage Boston. © State Bar of Texas 2012. Available to order at texasbarbooks.net. TWO MOST IMPORTANT LAWYERS OF THE LAST FIFTY YEARS 67 concluded his Watergate memoirs, The Right and the Power, with these words that summarize his ultimate triumph in “raising the bar”: From Watergate we learned what generations before us have known: our Constitution works. And during the Watergate years it was interpreted again so as to reaffirm that no one—absolutely no one—is above the law.29 JAMES A. BAKER, III The case for pragmatic idealism is based on an optimis- tic view of man, tempered by our knowledge of human imperfection. It promises no easy answers or quick fixes. But I am convinced that it offers our surest guide and best hope for navigating our great country safely through this precarious period of opportunity and risk in world affairs.30 In their historic careers, Leon Jaworski and James A. Baker, III, ended up in the same place—the highest level of achievement in their respective fields as lawyers—though they didn’t start from the same place. Leonidas Jaworski entered the world in 1905 as the son of Joseph Jaworski, a German-speaking Polish immigrant, who went through Ellis Island two years before Leon’s birth and made a modest living as an evangelical pastor leading small churches in Central Texas towns. James A. Baker, III, entered the world in 1930 as the son, grand- son, and great-grandson of distinguished lawyers all named James A. -

Revised Brief of Petitioner for Salazar V. Buono

No. 08-472 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- KEN SALAZAR, Secretary of the Interior, et al., Petitioners, v. FRANK BUONO, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, THE AMERICAN LEGION, MILITARY ORDER OF THE PURPLE HEART, VFW DEPARTMENT OF CALIFORNIA, AMERICAN EX-PRISONERS OF WAR, VFW POST 385, AND LIEUTENANT COLONEL ALLEN R. MILIEFSKY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE (RETIRED), SUPPORTING PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- R. TED CRUZ KELLY J. SHACKELFORD ALLYSON N. HO Counsel of Record MORGAN, LEWIS HIRAM S. SASSER, III & BOCKIUS LLP ROGER L. BYRON 1000 Louisiana, Suite 4200 LIBERTY LEGAL INSTITUTE Houston, TX 77002 903 18th Street, Suite 230 (713) 890-5000 Plano, TX 75074 (972) 423-3131 (Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover) ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 AARON STREETT CHAD M. PINSON SAMUEL BURK RYAN L. BANGERT BAKER BOTTS LLP ELIZABETH HILDENBRAND One Shell Plaza WIRMANI 910 Louisiana TYLER M. SIMPSON Houston, TX 77002 BAKER BOTTS LLP (713) 229-1234 2001 Ross Avenue Dallas, TX 75201 JOHN J. MCNEILL, JR. (214) 953-6500 VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES J. NICHOLS GUEST 34th & Broadway VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS Kansas City, MO 64111 OF THE UNITED STATES, DEPARTMENT OF CALIFORNIA PHILIP B. ONDERDONK, JR. 1510 J Street, Suite 110 THE AMERICAN LEGION Sacramento, CA 95814 700 N. Pennsylvania Street Indianapolis, IN 46204 JAMES A. CLARK (317) 630-1224 AMERICAN EX-PRISONERS OF WAR DANIEL J. -

The Centennial of Armistice Day: a Remembrance of the Baker Botts Families Who Made a Difference in the First World War

The Centennial of Armistice Day: A Remembrance of the Baker Botts Families Who Made a Difference in the First World War November 8, 2018 BILL KROGER BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. ONE SHELL PLAZA 910 LOUISIANA HOUSTON, TX 77002 713.229.1736 713.229.2836 (FAX) [email protected] “The intellectual leap from a commemoration of the men trained here in 1917 to our duties as citizens today may seem a far- fetched one. But it’s not. That’s because, in a real sense, America’s entry into World War I marked our first emergence on the international scene. It was the beginning of a vast process which, despite a tragic setback during the years between World Wars I and II, continues to this day. That process has seen the United States attain, over the course of this century, a preeminence in world affairs unequaled by any other country in history—a preeminence which, uniquely, owes as much to the power of our ideals as to the force of our arms. The men who trained here surely understood and embraced this truth. They believed that the United States was not just a great power but a good one. Their belief explains their lofty idealism, their profound patriotism, their selfless willingness to give all for their country. The world may have changed dramatically since the 1st Officers’ Camp opened here in May, 1917. But one thing most assuredly has not. And that is the idea of America—one that transcends our military might and material abundance. It is an idea that may be summed up in one word: freedom. -

James A. Baker, III the Ultimate Negotiator and Counselor

The following article is excerpted from Raising the Bar: The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society by Talmage Boston, recently published by TexasBarBooks. This excerpt is taken from Chapter 2, which is devoted to Leon Jaworski and James A. Baker, III, believed by the author to be the two most important American lawyers of the last half-century. The excerpt below identifies the skill-set developed by Secretary Baker during his years in private practice, which caused him to progress from consummate transactional lawyer to ultimate power player for the federal government during the administrations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. James A. Baker, III The Ultimate Negotiator and Counselor “The case for pragmatic idealism is based on an optimistic view of man, tempered by our knowledge of human imperfection. It promises no easy answers or quick fixes. But I am con - vinced that it offers our surest guide and best hope for navigating our great country safely through this precarious period of opportunity and risk in world affairs.” 1 James A. Baker, III entered the world in 1930 as the son, grandson, and great- grandson of distinguished lawyers all named James A. Baker, 2 who each made a good living working at the Baker Botts law firm (formed by Baker’s great-grandfather) in Houston. Rising from a comfortable beginning, James A. Baker, III took his counseling, negotiating, and deal-making talents as far as they could go, making an impact at the White House; at the Com - merce, Treasury, and State departments; and at places around the world. -

Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy — 2017 Annual Report

2017 annual report Cover: The Barbara and Gerald D. Hines Research Lab This annual report covers the Year at a Glance 2 activities of the institute for Mission 3 fiscal year 2017 from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017. Honorary Chair 4 Director 5 Research Centers and Programs 6 Awards and Scholarships 7 Policy in the Classroom 8 Policy Areas 10 Students 36 Financial Summary 38 Board of Advisors 40 Experts 44 Donors 53 Year at a Glance 6 research centers 8 research programs 55 fellows, scholars and research staff 81 Rice faculty and affiliated scholars 101 events 124 blog posts 133 student interns 166 classes taught 201 countries reached on the web 228 publications 18,973 media citations 26,642 followers on social media 2 | Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Mission Rice University’s Baker By bringing statesmen, Institute for Public Policy is a scholars and students together, nonprofit, nonpartisan think the institute broadens the tank in Houston, Texas. The content and reach of its institute produces independent policy assessments and research on domestic and recommendations, and provides foreign policy issues with a an open forum for debate and focus on providing decision- discussion. makers in the public and private sectors with relevant and The institute educates students timely policy assessments and on public policy issues and recommendations. related subjects by offering courses at Rice University and sponsoring student intern and mentoring programs at home and abroad. 2017 Annual Report | 3 Honorary Chair’s Message 04.13.17 Former Secretary of State James A. Baker, III, presents humanitarian Marguerite Barankitse with the James A. -

Rosneft As a Mirror of Russia’S Evolution

THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY LORD OF THE RIGS: ROSNEFT AS A MIRROR OF RUSSIA’S EVOLUTION BY NINA POUSSENKOVA RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PREPARED IN CONJUNCTION WITH AN ENERGY STUDY SPONSORED BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY AND JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER RICE UNIVERSITY – MARCH 2007 THIS PAPER WAS WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE JOINT BAKER INSTITUTE/JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER POLICY REPORT, THE CHANGING ROLE OF NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES IN INTERNATIONAL ENERGY MARKETS. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THIS PAPER HAS BEEN REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE RELEASE. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND THE VIEWS EXPRESSED WITHIN ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S) AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY NOR THOSE OF THE JAPAN PETROLEUM ENERGY CENTER. © 2007 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY ABOUT THE POLICY REPORT THE CHANGING ROLE OF NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES IN INTERNATIONAL ENERGY MARKETS Of world proven oil reserves of 1,148 billion barrels, approximately 77% of these resources are under the control of national oil companies (NOCs) with no equity participation by foreign, international oil companies. The Western international oil companies now control less than 10% of the world’s oil and gas resource base. In terms of current world oil production, NOCs also dominate. -

Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy

2014 ANNUAL REPORT Mission Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank in Houston, Texas. The institute produces independent research on domestic and foreign policy issues with a focus on providing decision- makers in the public and private sectors with relevant and timely policy assessments and recommendations. By bringing statesmen, scholars and students together, the institute broadens the content and reach of its policy assessments and recommendations, and provides an open forum for debate and discussion. The institute educates students on public policy issues and related subjects by offering courses at Rice University and sponsoring student intern and mentoring programs at home and abroad. 04.22.14 Jim Krane, Wallace S. Wilson Fellow in Energy Studies, discusses his research with Baker Institute members at the annual Spring Roundtable Dinner. This annual report encompasses Honorary Chair 4 the activities of the institute for Founding Director 5 fiscal year 2014 from July 1, 2013, to June 30, 2014. Research Programs 6 Awards, Publications and Scholarships 7 Policy in the Classroom 8 Year at a Glance 10 20th Anniversary 11 Policy Areas 14 Students 34 Financial Summary 36 Board of Advisors 38 Experts 41 Donors 48 Honorary Chair’s Message 10.27.13 Honorary chair James A. Baker, III, with a section of the Berlin Wall, its graffiti restored by art conservators in time for the Baker Institute’s 20th anniversary celebration. The section, donated to Rice University in 2000, serves to commemorate Baker’s role in the German reunification process as U.S. secretary of state. -

James A. Baker, Iii

JAMES A. BAKER, III James A. Baker, III has served in senior government positions under three United States Presidents. He served as the nation's 61st Secretary of State from January 1989 through August 1992 under President George H. W. Bush. During his tenure at the State Department, Mr. Baker traveled to 90 foreign countries as the United States confronted the unprecedented challenges and opportunities of the post–Cold War era. Mr. Baker’s reflections on those years of revolution, war and peace—The Politics of Diplomacy—was published in 1995. Mr. Baker served as the 67th Secretary of the Treasury from 1985 to 1988 under President Ronald Reagan. As Treasury Secretary, he was also Chairman of the President's Economic Policy Council. From 1981 to 1985, he served as White House Chief of Staff to President Reagan. Mr. Baker's record of public service began in 1975 as Under Secretary of Commerce to President Gerald Ford. It concluded with his service as White House Chief of Staff and Senior Counselor to President Bush from August 1992 to January 1993. Long active in American presidential politics, Mr. Baker led presidential campaigns for Presidents Ford, Reagan and Bush over the course of five consecutive presidential elections from 1976 to 1992. A native Houstonian, Mr. Baker graduated from Princeton University in 1952. After two years of active duty as a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, he entered the University of Texas School of Law at Austin. He received his J.D. with honors in 1957 and practiced law with the Houston firm of Andrews and Kurth from 1957 to 1975. -

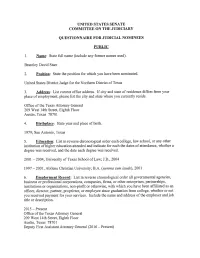

(Include Any Former Names Used). Brantley David Starr 2. Position

UNITED SJ' ATES SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY QUESTIONNAIRE FOR JUDICIAL NOMINEES PUBLIC 1. Name: State full name (include any former names used). Brantley David Starr 2. Position: State the position for whieh you have been nominated. United States District Judge for the Northern District of Texas 3. Address: List current office address. If city and state of residence differs from your place of employment, please list the city and state where you currently reside. Office of the Texas Attorney General 209 West 14th Street, Eighth Floor Austin, Texas 7870 I 4. Birthplace: State year and place of birth. 1979; San Antonio, Texas 5. Education: List in reverse chronological order each college, law school, or any other institution of higher education attended and indicate for each the dates of attendance, whether a degree was received, and the date each degree was received. 2001 -2004, University of Texas School of Law; J.D., 2004 1997-2001, Abilene Christian University; B.A. (summa cum laude), 2001 6. Employment Record: List in reverse chronological order all governmental agencies, business or professional corporations, companies, firms, or other enterprises, partnerships, institutions or organizations, non-profit or otherwise, with which you have been affiliated as an officer, director, partner, proprietor, or employee since graduation from college, whether or not you received payment for your services. Include the name and address of the employer and job title or description. 2015 - Present Office of the Texas Attorney General 209 West -

John and Dominique De Menil, Schlumberger, and Baker Botts by Bill Kroger a Banker’S Box Was Pulled Off a Dusty Shelf from a Massive Offsite Archive

An 80-Year Relationship: John and Dominique de Menil, Schlumberger, and Baker Botts By Bill Kroger A banker’s box was pulled off a dusty shelf from a massive offsite archive. Slowly, it wound its way to the Baker Botts offices at One Shell Plaza in Houston Texas. It was unloaded on floor 32. And two volumes of the box were put on a cart and brought up to floor 36. There they sit, while I write this essay – Baker Botts partner Joe Hutcheson’s bound volumes from the 1961 initial public offering of Schlumberger, Ltd., an IPO that changed the City of Houston. The motivation for this activity comes from a new book, “Double Vision,” by William Middleton. Middleton tells an epic tale about the story of the remarkable marriage and lives of John and Dominique de Menil and their company, Schlumberger Ltd. It took 12 years to write, with funding from everyone from Lynn Wyatt and Louisa Stude Sarofim, to the Brown Foundation and the Houston Endowment. It tells a nearly 200-year story, starting in 19th Century France and ending in 21st Century Houston. It is one of the best books written on the City of Houston. Like one of Plutarch’s lives, it also provides a guide for how to live a meaningful life and improve the conditions of a community. Baker Botts was honored to play an important role in this remarkable story. The firm first represented Schlumberger in 1932, when Schlumberger opened an office in Texas. Hutcheson, who represented Schlumberger for many decades and later served on the Schlumberger board, observed, “At that time it had one truck, with the necessary equipment for conducting electrical well surveys.” Jean and Dominique, who was one of the children of legendary founder Conrad Schlumberger, worked for the company in France during this time. -

Conference on State and Federal Appeals

UTCLE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF LAW 15th Annual CONFERENCE ON STATE AND FEDERAL APPEALS Earn up to 15.25 Hours of Credit Including 2.25 Hours of Ethics Credit Specialization Expected for: Civil Appellate Law, Civil Trial Law, Criminal Law, Personal Injury Trial Law June 1*, 2-3, 2005 *Optional Wednesday Evening Writing Session with Timothy Terrell, Emory University School of Law Four Seasons Hotel Austin, Texas WWW.UTCLE.ORG • 512-475-6700 15TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE ON STATE AND FEDERAL APPEALS June 1*, 2-3, 2005 • Four Seasons Hotel • Austin Earn up to 15.25 Hours of Credit Including 2.25 Hours of Ethics Credit WEDNESDAY EVENING, JUNE 1, 2005 11:00 a.m. .75 hr 3:25 p.m. .67 hr Presenting the Facts: Making the Law Look Mock Jury Charge Conference 6:00 p.m. 3.00 hr Inevitable Following an update on charge law in Texas, watch Most lawyers treat facts as grubby material to experienced practitioners argue the charge and The Principles of Effective Writing and overcome to get to “the law.” This mistake can be make objections/preserve error in a mock charge Editing overcome by a principled approach to storytelling. conference. Writing and editing skills do not improve by search- Timothy Terrell, Atlanta, GA Hon. Tracy Christopher, Houston ing for discrete “tips,” but instead through attention Daryl L. Moore, Houston to more fundamental principles that dominate the Gwen J. Samora, Houston communication process. 11:45 a.m. .75 hr Timothy Terrell, Atlanta, GA Court of Appeals Panel 4:05 p.m. 1.00 hr ethics Discussion of various issues with four court of appeals Professional Responsibility THURSDAY MORNING, JUNE 2, 2005 justices. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. Plaintiff, V

Case 4:12-cv-00003 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 01/03/12 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. § § Plaintiff, § § v. § § Case No. 4:12-cv-3 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND § EXCHANGE COMMISSION § § Defendant. § ORIGINAL COMPLAINT I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiff Baker Botts L.L.P. (“Baker Botts”) brings this action under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552, for injunctive and other appropriate relief, seeking release of documents in the Defendant’s possession that the Defendant has improperly withheld. II. PARTIES 2. Plaintiff, Baker Botts, is an international law firm with 725 lawyers and a network of 13 offices around the world. Baker Botts’s principal office and headquarters is located at One Shell Plaza, 910 Louisiana Street, Houston, Texas 77002. 3. Defendant, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), is a department of the executive branch of the United States Government, and is an agency within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. § 552(f). Case 4:12-cv-00003 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 01/03/12 Page 2 of 8 III. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 4. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction over this action and personal jurisdiction over the parties pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). This court also has jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331. 5. Venue is proper in the Southern District of Texas pursuant to 5 U.S.C.