Let's Take the Con out of Factor Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14.54 F16 Lecture Slides: Production Functions

14.54 International Trade Lecture 10: Production Functions 14.54 Week 6 Fall 2016 14.54 (Week 6) Production Functions Fall 2016 1 / 20 Today's Plan 1 Midterm Results 2 Properties of Production Functions (2 Factors) 3 Isoquants 4 Input Choice and Cost Minimization 5 Relative Factor Demand Graphs on slides 7, 10-17, and 19 are courtesy of Marc Melitz. Used with permission. 14.54 (Week 6) Production Functions Fall 2016 2 / 20 Introduction We will now introduce another factor of production: capital Can also think about other production factors: land, skilled versus unskilled labor, ... 14.54 (Week 6) Production Functions Fall 2016 3 / 20 What issues can be addressed when production requires more than a single factor? In the short-run, some factors are more ‘flexible’ than others: how quickly and at what cost can factors move from employment in one sector to another? Example of labor and capital: After a U.S. state is hit with a regional shock, unemployment rate falls back to national average within 6 years (most inter-regional employment reallocations also involve worker reallocations across sectors) In comparison, capital depreciates over 15-20 years and structures over 30-50 years In the short-run, labor is more ”flexible” than capital across sectors Distributional consequences across factors from changes in goods prices even in the long run 14.54 (Week 6) Production Functions Fall 2016 4 / 20 Production Function Under constant returns to scale, a production function with one factor can be summarized by a single number: unit input requirement (an overall productivity index) With more than one factor, a production function also characterizes the substitutability between the factors of production (as well as an overall productivity index) We will now assume that QC = FC (KC , LC ) and QF = FF (KF , LF ) We will continue to assume constant returns to scale: F (tK , tL) = tF (K , L) for any t > 0 And will also assume diminishing marginal returns to a single factor .. -

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement National Income :- • National income is the money value of all the final goods and services produced by a country during a period of one year. National income consists of a collection of different types of goods and services of different types. • Since these goods are measured in different physical units it is not possible to add them together. Thus we cannot state national income is so many millions of meters of cloth. Therefore, there is no way except to reduce them to a common measure. This common measure is money. Basic Concepts in National Income:- • Gross domestic product • Gross domestic product at constant price and at current price • Gross domestic product at factor cost and Gross domestic product at market price • Net domestic product • Gross national product • Net national Product • Net national product at factor cost or national income Gross Domestic Product • Gross domestic product is the money value of all final goods and services produced in the domestic territory of a country during an accounting year. Gross Domestic Product at Constant price and Current price • GDP can be estimated at current prices and at constant prices. If the domestic product is estimated on the basis of the prevailing prices it is called gross domestic product at current prices. • If GDP is measured on the basis of some fixed price, that is price prevailing at a point of time or in some base year it is known as GDP at constant price or real gross domestic product. GDP at Factor cost and GDP at Market price • The contribution of each producing unit to the current flow of goods and services is known as the net value added. -

Factor Proportions, Linkages and the Open Developing Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Riedel, James Working Paper — Digitized Version Factor proportions, linkages and the open developing economy Kiel Working Paper, No. 20 Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Riedel, James (1974) : Factor proportions, linkages and the open developing economy, Kiel Working Paper, No. 20, Kiel Institute of World Economics (IfW), Kiel This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/46955 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Kieler Arbeitspapiere Kiel Working Papers Working Paper No. 20 FACTOR PROPORTIONS, LINKAGES 'AND THE OPEN DEVELOPING ECONOMY by James,Riedel •\ Institut fiir Wfeltwirtschaft an der Universitat Kiel Kiel Institute of World Economics Department IV 2300 Kiel, Dusternbrooker Weg 120 Working Paper No. -

National Income and Product Accounts

LECTURE NOTES_PARUL JAIN National Income and Product Accounts • National income and product accounts are data collected and published by the government describing the various components of national income and output in the economy. • The Department of Commerce is responsible for producing and maintaining the “National Income and Product Accounts” that keep track of GDP. LECTURE NOTES_PARUL JAIN Need for National Income Accounting • Indicates Economic Growth: – it indicates performance and the level of economic growth in an economy. The data on national income and per capita display the true picture of the health of an economy. If both are increasing continuously, it surely reflects an increase in economic welfare, otherwise not. • Helps in Policy Formulation: – Statistical data on national income not only helps in making economic analysis but also helps in policy formulation. Moreover it not only helps in formulating fiscal policy, monetary policy, foreign trade policy but also helps in making modifications and amendments wherever necessary. LECTURE NOTES_PARUL JAIN Need for National Income Accounting • Helpful in Making Comparisons – it helps us in comparing national income and per capita income of our country with those of other countries. This may lead us to make suitable changes in our plans and approach to achieve rapid economic development of our country. • Helpful to Trade Unions – National accounts throw light on distribution of factor incomes which is very helpful to trade unions and other labour organizations in making rational analysis of the remuneration the laborers are getting. • Distribution of income – National income accounting describes distribution of national income in terms of factors like interest, rent, profit & wages. -

1.4 I Production Method of Calculating National Income

1.4 I Production Method of Calculating National Income In product method or value added method, we calculate the aggregate annual value of goods and services produced during a year. How to go about doing this? Do we add up the value of all goods and services produced by all the firms in an economy? The following example will help us to understand. Let us suppose that there are only two kinds of producers in the economy - wheat producers (or the farmers) and the bread makers (rhe bakers). The wheat producers grow wheat and they do not need any input other than human labour. They sell a part of the wheat to the bakers. The bakers do not need any other raw materials besides wheat to produce bread. Let us suppose that in a year the total value of wheat that the farmers have produced is ^100. Out of this they have sold ^50 worth of wheat to the bakers. The bakers have used this amount of wheat completely during the year and have produced ^200 worth of bread. What is the value of total production in the economy? If we follow the simple way of aggregating the values of production of the sectors, we would add ^200 (value of production of the bakers) to ^100 (value of production of farmers). The result will be ^300. A little reflection will tell us that the value of aggregate production is not ^300. The farmers had produced ^100 worth of wheat for which it did not need assistance of any inputs. Therefore, the entire ^100 is rightfully the contribution of the farmers. -

Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation Or Scarcity?

MATTHEW ROGNLIE Massachusetts Institute of Technology Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation or Scarcity? ABSTRACT In the postwar era, developed economies have experienced two substantial trends in the net capital share of aggregate income: a rise dur- ing the last several decades, which is well known, and a fall of comparable magnitude that continued until the 1970s, which is less well known. Over- all, the net capital share has increased since 1948, but once disaggregated this increase turns out to come entirely from the housing sector: the contribution to net capital income from all other sectors has been zero or slightly negative, as the fall and rise have offset each other. Several influential accounts of the recent rise emphasize the role of increased capital accumulation, but this view is at odds with theory and evidence: it requires empirically improbable elastici- ties of substitution, and it presumes a correlation between the capital-income ratio and capital share that is not visible in the data. A more limited narra- tive that stresses scarcity and the increased cost of housing better fits the data. These results are clarified using a new, multisector model of factor shares. ow is aggregate income split between labor and capital? Ever since HDavid Ricardo (1821) pronounced it the “principal problem of Polit- ical Economy,” this question of distribution has both puzzled and inspired economists. Views differ. In one popular interpretation, the division between labor and capital remains remarkably stable over time: John Maynard Keynes (1939) called this stability “one of the most surprising, yet best-established, facts in the whole range of economic statistics” (p. -

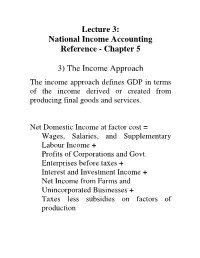

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5 3) The Income Approach The income approach defines GDP in terms of the income derived or created from producing final goods and services. Net Domestic Income at factor cost = Wages, Salaries, and Supplementary Labour Income + Profits of Corporations and Govt. Enterprises before taxes + Interest and Investment Income + Net Income from Farms and Unincorporated Businesses + Taxes less subsidies on factors of production Net Domestic Income at market prices = Net Domestic Income at factor cost + Indirect taxes less subsidies Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at market prices = Net Domestic Income at market prices + Capital Consumption Allowances + Statistical Discrepancy OTHER NATIONAL ACCOUNTS Gross National Product (GNP) = Gross Domestic Product (GDP) + Net Investment from Non-residents = 1154.9 – 84.9 = 1070 Example – The production of cars in the Honda factory in Alliston, Ontario is included in both Canadian GDP and GNP. But GNP excludes profit sent to foreign shareholders of Honda, but this profit is included in Canadian GDP. Net Domestic Product (NDP) = GNP – Depreciation = 1070–155 = 915 Net National Income at Basic Prices (NNI) = NDP- Taxes less subsidies on factors of production - Indirect taxes less subsidies = 915 – 53.8 – 84.4 = 776.8 Personal Income = NNI – Undistributed Corporate Profits + Govt. Transfer Payments = 776.8 – 49.0 +71.3 = 848.1 Disposable Income = PI – Personal Taxes = 848 – 152.2 = 695.9 Nominal GDP Versus Real GDP Nominal GDP is the GDP measured in terms of the price level at the time of measurement (unadjusted for inflation). Problem: How can we compare the market values of GDP from year to year if the value of money itself changes because of inflation or deflation? - Compare 5% increase in Q with no change in P and 5% increase in P with no change in Q - The way around this problem is to deflate GDP when prices rise and to inflate GDP when prices fall. -

The Field of International Trade Had Considered a Wide Array of Factors

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INTERNATIONAL TRADE, MULTINATIONAL ACTIVITY, AND CORPORATE FINANCE C. Fritz Foley Kalina Manova Working Paper 20634 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20634 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2014 Forthcoming in the Annual Review of Economics 7, doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115453. Foley thanks the Division of Research of the Harvard Business School for financial support. Manova thanks the Stanford Center for International Development for financial support. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2014 by C. Fritz Foley and Kalina Manova. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. International Trade, Multinational Activity, and Corporate Finance C. Fritz Foley and Kalina Manova NBER Working Paper No. 20634 October 2014 JEL No. F10,F20,F23,F36,G3 ABSTRACT An emerging new literature brings unique ideas from corporate finance to the study of international trade and investment. Insights about differences in the development of financial institutions across countries, the role of financial constraints, and the use of internal capital markets are proving central in understanding international economics. The ability to access financial capital to pay fixed and variable costs affects choices firms make regarding export entry and operations, and, as a consequence, influence aggregate trade patterns. -

Basic Concepts of National Accounts Aggregates

CHAPTER 2 BASIC CONCEPTS OF NATIONAL ACCOUNTS AGGREGATES Introduction 2.1 Various concepts of national income and taken of the rental of buildings which are related aggregates used in national accounts owned and occupied by the owners connote a particular meaning which may not themselves. Own account construction necessarily conform to the one used in activities are also similarly to be included. common parlance. It is, therefore, necessary However, certain other activities like services that these are made familiar to the users to of house-wives are excluded from production enable them to appreciate these in right mainly due to the problem of measurement. perspective. It is with this objective that it Also excluded are illegal activities such as has been considered necessary to refer to smuggling, black marketing, etc. these in this publication. The basic concepts and definitions of the terms used in national 2.4 Another important feature of the measure is accounts largely follow those given in the that it is an unduplicated value of output or in SNA. It is intended to give in the following other words only the value added at each paragraphs the major concepts used in stage of processing is taken into account National Accounts Statistics and the inter while measuring the total, i.e., in the relationship particularly of those relating to measurement of national output a distinction macro-economic aggregates of national is made between "final" and "intermediate" product, consumption, saving and capital products and unduplicated total is one that is formation. confined to the value of the final products and excludes all intermediate products. -

The Environment As a Factor of Production

The Environment as a Factor of Production Timothy J. Considine and Donald F. Larson Abstract This paper develops a model of environmental resource use in production with an empirical analysis of how electric power companies consume and bank sulfur dioxide pollution permits. The model considers emissions, fuels, and labor as variable inputs with quasi-fixed inputs of permits and capital. Incorporating information from permit markets allows us to distinguish between user costs and asset shadow values. Our findings indicate that firms are holding stocks of pollution permits for reasons other than short-term cost savings. The results also reveal substantial substitution possibilities between emissions, permits stocks, and other factors of production. We speculate that anticipated secondary markets for carbon-offset inventories related to the flexibility mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol will have similar effects for greenhouse-gas emitting firms. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3271, April 2004 The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the view of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. Policy Research Working Papers are available online at http://econ.worldbank.org. Timothy J. Considine is a Professor of Natural Resource Economics at Pennsylvania State University; Donald F. -

Presentation #14: Factor & Labor Markets

Presentation #14: Factor & Labor Markets In the previous couple of units we’ve been exploring the product market (both perfect competition and various forms of imperfect competition) to understand both the quantity firms produce & the prices they charge to maximize profits. This short unit explores the FACTOR market (also called “resources” or “inputs”). The main goal is understanding how economic factors or production (land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship) are used by firms to maximize profits. The factor that will be explored as an example in this unit will be LABOR. The goal is to better understand how firms in competitive markets decide how many workers to hire and what wages workers receive. SEE END OF THIS SLIDESHOW FOR INSTRUCTIONS ON ASSIGNMENT #8 (DUE FRIDAY 4/17 at 3:00) Video #1: Crash Course Introduces Labor Markets in 10 Minutes Review: What are the Four FACTORS of Production? Land: All natural resources that are used to produce goods and services. Labor: Any effort people devote to a task for which that person is paid. Capital: Physical Capital- Any human made resource that is used to create other goods and services. (Ex: machine) Human Capital- Any skills or knowledge gained by a worker through education and experience. (Ex: Education) Entrepreneurship: Ambitious & creative leaders who combine the other factors of production to create goods and services. Review: What are the payments made for the use of the factors of production called? Land is paid Rent Labor is paid Wage Capital is paid Interest Entrepreneurs are paid Profit In the product market (last unit), individuals pay businesses for goods and services (ex: buying products) In the FACTOR market (this unit), businesses pay individuals for the use of resources (ex: wages) The FACTOR we will examine in this unit as an example is LABOR REVIEW: Graphs for the Demand & Supply of LABOR Labor Market Equilibrium = Where Supply & Demand meet Video #2: Wages (the price of labor) is set by the Mr. -

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

CHAPTER 8 GROSS DOMESTC PRODUCT(GDP)-AN OVERVIEW 8.1 Domestic product is an indicator of overall generated through the production activity is production activity. GDP is a measure of distributed between the two factors of production. The level of production is production, namely, labour and capital, important because it largely determines how which receive respectively the salaries and much a country can afford to consume and it the operating surplus/mixed income of self also affects the level of employment. The employed. Thus the income approach GDP consumption of goods and services, both is the sum of compensation of employees, individually and collectively, is one of the gross operating surplus and gross mixed most important factors influencing the income plus taxes net of subsidies on welfare of a community. The concept of production. In the National Accounts GDP in the 1993 SNA framework has been Statistics of India, the production approach briefly discussed in the following paragraphs. GDP is considered firmer estimate; and the NAS presents the discrepancy with the expenditure approach GDP explicitly. 8.2 It should be noted, however, that GDP is not intended to measure the production taking Production approach GDP place within the geographical boundary of 8.3 GDP is a concept of value added. It is the the economic territory. Some of the sum of gross value added of all resident production of a resident producer may take producer units (institutional sectors, or place abroad, while some of the production industries) plus that part (possibly the total) taking place within the geographical of taxes, less subsidies, on products which is boundary of the economy may be carried out not included in the valuation of output.