Maintaining Secret Government Dossiers on the First Amendment Activities of American Citizens: the Law Enforcement Activity Exception to the Privacy Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Collection of the Works of David Lane

The Collection of the Works of David Lane “We Must Secure The Existence Of Our People And A Future For White Children” “Because The Beauty Of The White Aryan Woman Must Not Perish From The Earth” “A People Who Are Not Convinced Of Their Uniqueness And Value Will Perish” Table of Contents Personal Articles: Autobiography The Illegal and Malicious Imprisonment of David Lane The Final Address of David Lane to the Court upon Sentencing Revolution by Number 14 88 Precepts Poems 88 Lines and 14 Words Or was it just a dream? Viking Princess Goddess The Nation’s Faith Let the Valkyrie Ride Tall Man Crying Revenge Gods of Our Blood Return of the Gods Ode to Bob Mathews Farewell White Woman Short Story: KD Rebel Pyramid Prophecy: Mystery Religions and the Seven Seals Why Wotanism and the Pyramid Prophecy? The Pyramid Prophecy Miscellaneous: The Death of the White Race White Genocide Manifesto Open Letter to a Dead Race An Open Letter to the Reality Deniers Reality Check Betrayal The Former Yugoslavia Police Powers What to Think vs. How to Think Universalist Imperialism The Price of Continued Reality Denial Gates of the Mind Wotansvolk First Law of Nature Race to Extinction Sex and Women England – Ireland – Scotland Now or Never Maynard C Campbell Fanaticism of Desperation Moral Authority Modern Freemasonry Drugs and Government Misplaced Compassion Technology Leads to Our Extinction Intelligence Gathering Security and Infiltration Strategy Polygamy Adaptability Then and Now Valhalla: Fact or Fiction? Who is White? Wotanism (Odinism) Wotanism Lecture Counterfeit Culture Reality Denial Open Letter to McVeigh PS: It Only Gets Worse Tim Martyrs New World Order Guerilla Radio Nature’s Command Misdirected Hate Money Crossing the Rubicon Open Letter to All Christians Dissension in the Ranks Christian Rightwing American Patriots Personal Articles Autobiography Introduction The near impossibility of ignoring one's own ego made an accurate recording of my own life a difficult task. -

WBS 022019.Pdf

1/ 24/2019 Columns> Now Its William Barr When Will Christians And Conservatives Stop Making Excuses For Donald Trump? ( k,,, 6, f JUDAISM ' S z.' 0 • lq Phillip- F- Toumey/p/99206328/ categary= 15986016) S Store.aspxtl/JudTaiarmsS^trange-Gods-Book-ByeMichaelaloffman/ p/805852SOIwhgory=15986016) f\ Li \ L. i'. RCH i_ l. THE Stora.asp UThe- Reel- Lincoln-By-Thomas- I . I N C O N I Dilorenzo/ pI71957497/ 15986016) StoreasPrdFl/Godas- category= FOR TI-IE IIllr v (/ ALCOHOLIC For-The-AlcoholiceBook 3yJe ry-Dunn/p/83557886/category=15986016) WAR ma rift Birmi, Cat i 2 rrr tore.espolAVaMs-A-Rackagpl66353093/ rategory= 15986016) PURCI-LASE. PH F BOOK Stare.aspxIl/ George-Washington Farewell- Address- Booklet- a "•' Distrlbuteda3y- Dr-Chuck- Baldwin/p/88200807/category=15986016) IStore.asptdfl/ Second-Treatise-of-Government- ByJahmlacke/p/ 60029265Ieategory= 15986016) FR FDC R IC RA S T 1 A T Stweasp>dWThe-Law/P/ 66353092/category= 15986016) Now It' s William Barr When Will Christians And Conservatives Stop Making Excuses For Donald Trump? Published: Thursddi, January 24, 2019 Download tree computerized mp3 audio Me of this coin( https://chuckbaldwinitve.contPortals/1lCootant/Files/calumnaudioP2019_ 01- 24_CBColumn_audlo.mp3) Don... 3/9 htlps:// chudcbakhviMive con Micles/ abid/ 109IIDI3833/ Now- la-WMlam- Barr-When-Wi6{: hristians-And- Conservatives- Stop- Makin9Exases-For- CrIIM16Z- 1/ 24/ 2019 Columns> Now It's William Bart: When Will Christians And Conservatives Stop Making Excuses For Donald Trump? Okay, we all know how awful Hillary Clinton is, We all know that Donald Trump said all the right things( well, many of the right things) on the campaign trail. -

State of IDAHO, Plaintiff-Appellant, V. Lon T. HORIUCHI, Defendant-Appellee

Idaho v. Horiuchi, 253 F. 3d 359 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 2001 State of IDAHO, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Lon T. HORIUCHI, Defendant-Appellee. No. 98-30149. United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. Argued and Submitted December 20, 2000 Filed June 5, 2001 (Vacated September 2001) 360*360 361*361 Stephen Yagman, Special Prosecutor for State of Idaho, on the brief and argued, Marion R. Yagman, Special Deputy Prosecutor, Joseph Reichmann, Special Deputy Prosecutor, Kathryn S. Bloomfield, Special Deputy Prosecutor, on the brief, Venice Beach California, and Ramsey Clark, Special Deputy Prosecutor, New York, New York, argued, the cause for the plaintiff-appellant. Adam S. Hoffinger, Earl J. Silbert, Piper & Marbury, L.L.P., Washington, D.C., argued the cause for the defendant-appellee. Seth Waxman, Acting United States Solicitor General, of the United States, United States Department, of Justice, Washington, D.C., argued the cause for Amicus Curiae, United States of America, on behalf of the defendant-appellee. George Culvahouse, O'Melveny & Myers, Washington, D.C., Griffin B. Bell, Benjamin Civiletti, William Barr, and William Webster, as amici curiae for defendant-appellee. Before: MARY M. SCHROEDER, Chief Judge, and PROCTER HUG, JR., ALEX KOZINSKI, PAMELA ANN RYMER, ANDREW J. KLEINFELD, MICHAEL DALY HAWKINS, SIDNEY R. THOMAS, BARRY G. SILVERMAN, SUSAN P. GRABER, WILLIAM A. FLETCHER and RICHARD A. PAEZ, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge KOZINSKI; Partial Concurrence and Partial Dissent by Judge WILLIAM A. FLETCHER; Dissent by Judge MICHAEL DALY HAWKINS. KOZINSKI, Circuit Judge: It was, in the words of Justice Kennedy, the genius of the Founding Fathers to "split the atom of sovereignty." U.S. -

FBI Sniper Dropped from Davidian Wrongful-Death Suit

PAGE A2 / SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2000 ]!0a0^tngt(in ^tnteo FBI sniper dropped from Davidian wrongful-death suit ers, head of the hostage-rescue were consistent with the round Agent Riley later retracted'his fire took place there by govern for many years. ment police officers," altliough he team, said that while the Davidians By Jerry Seper The Tfexas court's decision is the used by Agent Horiuchi in the statement, saying he heard no gun THE WASHINGTON TIMES did shoot at the agents, the FBI did second time that accusations have death of Vickie Weaver shots from the sniper post. Bureau has declined to elaborate. of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Agent Horiuchi, a 15-year FBI not fire "a single shot" because A federal court has dismissed an been dismissed against the veteran The Rangers' report raised questions about the FBI's role in (ATF) agents involved in a gun- veteran and graduate of the U.S. they did not "acquire clear and FBI sharpshooter from a lawsuit agent. In 1998, a federal judge in Military Academy at West Point, identifiable targets." brought by survivors of the 1993 Idaho dismissed manslaughter Uie 51-day standoff, now the sub fight at the Davidian site on Feb. 28, 1993, had occupied the same N.Y., has not been available for In the Ruby Ridge case, Agent siege at the Branch Davidian com charges brought against Agent ject of inquiries by former Mis Horiuchi testified he did not mean souri Sen. John Danforth. The sniper posts. comment. He told Justice investi pound near Waco, Tbxas, saying Horiuchi by state officials in the gators shortly after the Wacoraid to shoot Mrs. -

Choose Who You Will Serve

Citizenzhip Choose Who You Will Serve by Alfred Adask Several articles in Volume 10 The 9th Circuit Court of Ap- degree murder instead of man- No. 1 explored the concept of peals has answered that ques- slaughter. citizenship. This next article tion two different ways [crimi- Then why didnt they? Pro- continues that exploration with nally, he could not be pros- fessional courtesy for fellow gov- a series of email which express ecuted; civilly, he could] and ernment employees? common concerns about govern- its now being asked to rule When Horiuchi fired, he was ment abuse but neglect to con- again. mindlessly shooting to kill on sider the relevance of citizen- The case is highly signifi- sight, firing blindly a 200-yard ship. cant, and raises issues of the shot through a door, the peti- For example, the first seg- greatest importance and of na- tion states. Mrs. Weaver was ment of this article is based on tional concern, said Stephen killed by a wild-headed govern- an email entitled 9th Circuit Yagman, a Los Angeles attorney ment sniper in violation of our Rules Murder OK If Its Doing who is working with Boundary Constitution, and still is dead. Your Job from Jail4 Judges.1 County Prosecutor . to pros- The allegation that Horiuchi This email focused on the law- ecute FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi for was mindless and wild- suits and criminal charges that manslaughter. If Horiuchi cant headed justifies charging him have stemmed from the 1992 be charged, Yagman said, This with second-degree murder standoff between federal agents changes the entire law with re- rather than first-degree murder and Randy Weavers family at the spect to the use of force. -

FORENSIC PSYCHOLOGY Credits: 4

Subject: FORENSIC PSYCHOLOGY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Forensic Psychology: Introduction and overview, Historical Perspective, Fields of Forensic Psychology, Education and Training, Global perspective in the field of forensic science: - history, development, education and training Organizational setup of forensic science lab and other national & international agencies: - FSL, CFSL, GEQD, FPB, NICFS, CID,CBI, Central Detective Training Schools, NCRB, NPA, Mobile Forensic Science Laboratories, IB, CPO, FBI, CIA, CSI, DAB, DEA, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Psychology and law, Understanding the role and duties of criminal investigators, qualification of a forensic scientist, Ethical Issues in Forensic Science: - defining ethics, professional standards for practice of criminalistics, code of conduct for expert witnesses, sanction against expert for unethical conduct, Expert witness, Civil commitment Forensic Medicine: Global Medical Jurisprudence, Legal Procedure in India: - Police inquest, Magistrate’s inquest, Coroner’s inquest, Oath and affirmation. Documentary evidence: - Medical certificates, medical reports, dying declaration. Understanding laws and ethics of medical practice Suggested Readings: 1. David Canter, Forensic Psychology, Oxford University Press 2. Alan M. Goldstein, Handbook of Psychology, Forensic Psychology, John Wiley & Sons 3. Curt R. Bartol, Introduction to Forensic Psychology: Research and Application, Sage Publications (CA) 4. Joshua Duntley, Evolutionary Forensic Psychology: Darwinian Foundations of Crime and -

A HISTORY of the AMERICAN MILITIA MOVEMENT: America’S Shooting Edge by Nita M

A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN MILITIA MOVEMENT: America’s Shooting Edge By Nita M. Renfrew©2000 The strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort to protect themselves against tyranny in government. Thomas Jefferson PART I: Broken Seal Chapter 1 SECRET MILITIA I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country. Nathan Hale I knew already there was something mean amiss in America when a federal building was bombed in 1995, and soon after, news of Militias training for battle, quoting Thomas Jefferson, became commonplace. Until that time, I had investigated conflicts between peoples and governments far away, mainly in the Middle East and Central America. Now, sensing that the important story was moving to my own homeground, I turned my sights accordingly. What I found out about the Oklahoma bombing did not really surprise me. What I found out about the Militias, however, would change my life forever. It was in the spring of 1996 that I had my first Militia interview, with the bearded commander of an underground citizen Militia, at a remote place in the countryside. I shall call him Tom Church to protect his identity. We rendezvoused early one morning at a place in the state of New York which I cannot disclose. When I arrived, he was waiting for me, standing next to his van on a dirt road a few hundred feet from the highway. Tall and slender, in his late forties, he wore slacks and a t-shirt, not fatigues. -

The Origins of the Militia Movement Robert H

To Shake Their Guns in the Tyrant's Face: Libertarian Political Violence and the Origins of the Militia Movement Robert H. Churchill http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=327258 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. the origins of the militia movement: violence and memory on the suburban-rural frontier Sometimes change is sudden, and so dramatic that we can hardly believe our eyes. On November 9, 1989, I came home from teaching high school and turned on the television. I had followed the events in Eastern Europe closely that fall, but it still took me twenty minutes to fathom the live im- ages of young people dancing atop a concrete wall. I simply could not grasp what I was seeing. The newscasters reporting the fall of the Berlin Wall were themselves speechless. Sometimes change is imperceptible, until one day we are forced to confront a new state of affairs and realize that it has been twenty years in the making. I grew up in a variety of communities, urban, suburban, and rural. In one of those rural communities I once attended a Fourth of July celebration in a parking lot in the middle of town. It was a tailgate party attended by most of the town’s high school students, who stood in a small crowd drinking beer, in wholesale violation of the town’s open container laws and the state’s minimum age regulations. At the entrance to the parking lot, about ‹fty yards from the crowd, the town’s chief of police sat in his cruiser. -

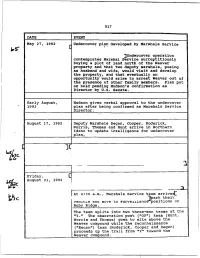

Report of Ruby Ridge Task Force

517 DATE EVENT May 27, 1992 Undercover plan developed by Marshals Service ] Undercover operation contemplates Marshal Service surreptitiously buying a plot of land north of the Weaver property and that two deputy marshals, posing as husband and wife, would visit and develop the property, and that eventually an opportunity would arise to arrest Weaver out of the presence of other family members. Plan put on hold pending Hudson's confirmation as Director by U.S. Senate. Early August, Hudson gives verbal approval to the undercover 1992 plan after being confirmed as Marshals Service Director. August 17, 1992 Deputy Marshals Degan, Cooper, Roderick, Norris, Thomas and Hunt arrive in Northern Idaho to update intelligence for undercover plan. ][ ] Friday, [ ] August 21, 1992 At 4:30 a.m., Marshals Service team arrives [ ]park their vehicle ana move to surveillance positions on Ruby Ridge. The team splits into two three-man teams at the "Y." The observation post ("OP") team (Hunt, Norris and Thomas) goes to site above the Weaver compound while the reconnaissance ("Recon") team (Roderick, Cooper and Degan) proceeds up the trail from "Y" toward the Weaver compound. 518 DATE EVENT Friday, ]the Recon team joins the OP team August 21, 1992 at the observation post above the Weaver compound[ ] The Recon team proceeds to area 200-250 yards from the Weaver cabin where Roderick tosses rocks in the direction of the Weaver compound. The Recon team moves to garden/spring house area below the Weaver cabin. At 10:00 a.m., while Recon team gets ready to leave garden/spring house area,[ ] at the observation post, radios that a vehicle is approaching and that the Weavers are responding. -

1-1.L-L U Vial

1-1.l-L U vial L 1-11 Lr 1 J.-1 -IL Lid-1,71vvytat 0p/14-- By James 13ovaan menstrual cycle of Weaver's teenage shack's door, he was shot from behind by ommended possible criminal prosecution FBI Director Louis Freeh last week an- daughter, and planned an arrest scenario FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi. As he struggled of federal officials and found that the rules nounced that no FBI agents would be fired around it." back to the cabin, his wife, Vicki. stood in of engagement "contravened the Constitu- or severely punished for their role In the On Aug. 21, 1992, six heavily armed, the doorway, holding a I0-month-old baby tion of the United States." Yet Deval botched attack on Idaho white separatist camouflaged U.S. marshals sneaked onto in her arms and calling for her husband to Patrick, assistant attorney general for Randy Weaver and his family in 1992, Mr. Weaver's property. Three agents hurry. The FBI sniper fired again and hit civil rights, rejected the findings last which led to the death of Mr. Weaver's son threw rocks to get the attention of Mr. Vicki Weaver in the temple, killing her in- month and concluded that the federal and wife. The announcement, which drew Weaver's dogs. As Mr. Weaver's 14-year- stantly. (Mr. Horiuchi testified in court agents had not used excessive force. denunciations from both the American old son. Sammy, and Kevin Harris, a 25- that he could hit within a quarter inch of a FBI Director Louis Freeh concluded Civil Liberties Union and the National Ri- year-old family friend living in the cabin, target at a distance of 200 yards.) that there was no evidence to show that fle Association, is the conclusion of a ran to see what the dogs were barking at, Reuters reported on Aug. -

No. 630, October 6, 1995

soC!: No. 630 ~)(.623 6 October 1995 Racist Rulers Grind the Poor j""', ~ THE POOR' WILL BE \iEARl\! t.I IA.J D II The legislation being rushed through all wings of the Democratic Party along Congress in the last two weeks signals with most of the so-called left joined a return not only to the days before the with Reagan/Bush in waging Cold 1930s New Deal but to conditions rem War II, which ended with capitalist iniscent of the 19th century. The already counterrevolution in East Europe and the threadbare social safety net-a by destruction of the Soviet Union. The product of generations of struggle by dismantling of social welfare programs working people-which has meant the call this country a "welfare state" is a considered sacrosanct, are under attack. in the U.S. is but the domestic side difference between subsistence and star cruel joke. Over the past generation, the Children, single mothers, the elderly, of the "New World Order" of unfettered vation for a large sector of the inner-city real wages of American working people immigrants, the ill or infirm-all the capitalist exploitation. For the men who and rural poor is now being tom to have fallen by 20 percent, while the most vulnerable layers of society are run Wall Street and the Fortune 500, shreds by both capitalist parties. chasm between rich and poor has wid being told to drop dead, literally. Time anyone who isn't producing profits The lopsided 87-12 Senate vote Jo ened enormously. One percent of U.S. -

The Bureaucratic Politics of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Political Science Undergraduate Honors Theses Political Science 12-2019 The Bureaucratic Politics of the Federal Bureau of Investigation Cooper Hearn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/plscuht Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Citation Hearn, C. (2019). The Bureaucratic Politics of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Political Science Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/plscuht/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bureaucratic Politics of the Federal Bureau of Investigation By Cooper Hearn Fulbright Honors Thesis, Fall 2019 Thesis Advisor: Dr. William Schreckhise Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Political Science in the Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences, the University of Arkansas, 2019 Abstract This is a comprehensive study of how the administrative powers of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) have evolved in response to external political forces. To analyze the changes made to FBI administrative powers, this project will assess theories of public administration, bureaucratic politics, various congressional statutes, court rulings, and executive policies that have affected the bureau’s capacity to perform investigations and intelligence operations. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis director, Dr. William Schreckhise.