David Tanenbaum Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

2016 30/50-Year+ Party

Official Publication of the Detroit Federation of Musicians – Local 5, AFM, AFL-CIO Volume 79 Number 3 Keynote Q3, 2016 2016 30/50-Year+ Party Photos pages 12–16 Home of the Pros Semi-annual Membership Meeting Special Features in This Issue • Keep up to date on union events • Tips for musician travel from AFM, • Ask questions; share suggestions other authorities, page 6 • Meet musicians you don’t know • Retired DSO violinist Ann Strubler premieres adoption documentary and Accompanied by usual refreshments symphonic composition, page 11 MONdaY, OCTOBER 17, 7 pm • Photos of 30/50-Year+ Party sponsors LOCAL 5 HospitalitY ROOM and attendees, pages 12–16 Keynote 3rd Quarter 2016 LIVE Links to What’s in This Issue The Music Stand . 1 Local 5 Support Line . 21 WindWords . 3 DFM Referral Gigs . .21 AFM Travel Tips . 6 Comedy Corner . 21 About eBilling Notification . 6 Member Directory Info . 22 Classified Advertising . 6 TEMPO Contributions . 23 Detroit Musicians Fund . 8 Labor Day Parade Info . 23 AmazonSmile . 8 Executive Board Minutes . 24–26 MusiCares Dental Clinic for Musicians . 9 Membership Survey . 28 Member Newsline . 10–11 UAW Chaplaincy Conference . 28 30/50-Year+ Party Coverage . 12–16 Closing Chord . 29 Welcome, New Members . 18–20 Missing eKeynote? . 29 Calendar of Local 5 Events Our Advertisers Local 5 Office Closings • Monday, Sept. 5, Labor Day (see you at the These fine folks helped bring you this issue parade; details on page 23) of Keynote . Your support will assure their • Monday, Oct. 10: Columbus Day continued advertising . • Tuesday, Nov. 8: Election Day Bugs Beddow . -

Toy Industry Product Categories

Definitions Document Toy Industry Product Categories Action Figures Action Figures, Playsets and Accessories Includes licensed and theme figures that have an action-based play pattern. Also includes clothing, vehicles, tools, weapons or play sets to be used with the action figure. Role Play (non-costume) Includes role play accessory items that are both action themed and generically themed. This category does not include dress-up or costume items, which have their own category. Arts and Crafts Chalk, Crayons, Markers Paints and Pencils Includes singles and sets of these items. (e.g., box of crayons, bucket of chalk). Reusable Compounds (e.g., Clay, Dough, Sand, etc.) and Kits Includes any reusable compound, or items that can be manipulated into creating an object. Some examples include dough, sand and clay. Also includes kits that are intended for use with reusable compounds. Design Kits and Supplies – Reusable Includes toys used for designing that have a reusable feature or extra accessories (e.g., extra paper). Examples include Etch-A-Sketch, Aquadoodle, Lite Brite, magnetic design boards, and electronic or digital design units. Includes items created on the toy themselves or toys that connect to a computer or tablet for designing / viewing. Design Kits and Supplies – Single Use Includes items used by a child to create art and sculpture projects. These items are all-inclusive kits and may contain supplies that are needed to create the project (e.g., crayons, paint, yarn). This category includes refills that are sold separately to coincide directly with the kits. Also includes children’s easels and paint-by-number sets. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

Daniele Lazzari Expresses Himself Through Music

DDANIELEANIELE LLAZZARIAZZARI Classical Guitarist Composer I Biography “Sweetness and elegance that get to the heart”. These words perfectly describe the way the Italian guitarist and composer Daniele Lazzari expresses himself through music. His talent was recognized first when he won international music competitions at the beginning of his career, as in Padua, Salerno, Lecce and Ancona. In fact, Mr. Lazzari is valued for the freshness of his interpretations which are always meditated and enriched by a brilliant instrumental technique. Mr. Lazzari has appeared in many prestigius concert venues through Europe and Asia. For instance, he gave concerts at the Festetics Castle in Keszthely, the Pisani Palace in Venice, the Ceramic Palace Concert Hall in Seoul. In 2016 he made his memorable debut at the famous Ferenc Liszt Music Academy in Budapest. His first solo CD, titled “Classical Guitar Jewels” has been acclaimed for the freshness and expressiveness which he has brought in the guitar masterpieces of the 20th century. VIRTUOSO GUITAR MUSIC OF SPAIN AND LATIN AMERICA is his new solo CD published by the Japanese label DA VINCI CLASSICS in 2018. Daniele Lazzari has devoted himself to chamber music with numerous projects. Stably he has performed with Italian violinist Varina Fortin, Hungarian flutist Emőke Geszti, Japanese soprano Noriko Ogawa, Korean soprano Eun Kyoung Suh, Italian tenor Giuseppe Coluzzi, Italian guitarist Luca Fabrizio and Hungarian guitarist Annamária Fábián. He has collaborated with the Extol Trio and the Estampas Quartet. Currently he is engaged in a new chamber music project with Italian flutist Claudio Marinone. The album “Sambossa”, recorded with flautist Mrs. -

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-Year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina Hello everyone, my name is Qiwen Wan. I am a first-year doctoral student in piano pedagogy major at the University of South Carolina. I am really glad to be here and thanks to SCMTA to allow me to present online under this circumstance. The topiC of my lightning talk is 5 stages for teaChing Alberto Ginastera's Twelve AmeriCan Preludes. First, please let me introduce this colleCtion. Twelve AmeriCan Preludes is composed by Alberto Ginastera, who is known as one of the most important South AmeriCan composers of the 20th century. It was published in two volumes in 1944. In this colleCtion, there are 12 short piano pieCes eaCh about one minute in length. Every prelude has a title, tempo and metronome marking, and eaCh presents a different charaCter or purpose for study. There are two pieCes that focus on a speCifiC teChnique, titled Accents, and Octaves. No. 5 and 12 are titled with PentatoniC Minor and Major Modes. Triste, Creole Dance, Vidala, and Pastorale display folk influences. The remaining four pieCes pay tribute to other 20th-Century AmeriCan composers. This set of preludes is an attraCtive output for piano that skillfully combines folk Argentine rhythms and Colors with modern composing teChniques. Twelve American Preludes is a great contemporary composition for late-intermediate to early-advanced students. In The Pianist’s Guide to Standard Teaching and Performing Literature, Dr. Jane Magrath uses a 10-level system to list the pieCes from this colleCtion in different levels. -

Feather Fingerboard Created by Ruiz Brothers

Feather Fingerboard Created by Ruiz Brothers Last updated on 2018-08-22 04:01:25 PM UTC Guide Contents Guide Contents 2 Overview 3 Feather Boarding 3 Fingerboard History 3 Use & Performance 3 Parts, Tools and Supplies 3 3D Printing 5 Wood Filament 5 Slice Settings 5 Support Settings 5 Raft Settings 5 Slicing Details 6 Raft & Support 6 Surface Finishing 7 Mounting Holes 7 Temperature & Colorations 7 CAD Model 7 Assembly 9 Install Standoffs to Feather 9 Feather Standoffs 9 Deck Installation 9 Install M2.5 Nuts 10 Remove Feather 10 Deck Standoffs 11 Install Wheels to Trucks 11 Install Trucks 11 Installed Trucks 12 Install Feather 12 Secure Feather to Deck 13 Fasten Standoffs 13 Make, Modify, Share 13 © Adafruit Industries https://learn.adafruit.com/feather-fingerboard Page 2 of 13 Overview Feather Boarding This is a 3D printed fingerboard specifically designed for the Adafruit line of Feather boards. It's similar to a standard fingerboard but features special mounting holes for installing an Adafruit Feather. The deck was 3D printed using ColorFabb's PLA/PHA bambooFill (https://adafru.it/xub). This material is 70% colorfabb PLA and 30% recycled wood fibers. Fingerboard History From Wikipedia (https://adafru.it/xuc): A fingerboard is a working replica (about 1:8 scaled) invented by Jaken Felts, of a skateboard that a person "rides" by replicating skateboarding maneuvers with their hand. The device itself is a scaled-down skateboard complete with moving wheels, graphics and trucks.[1] A fingerboard is commonly around 10 centimeters long, and can have a variety of widths going from 29 to 33 mm (or more). -

Simon Powis, Guitar (Australia) New Opportunities for a Twenty-First Century Guitarist 6:00 - 7:15 P.M

The 16th Annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival June 3 - 5, 2016 Vieaux, USA SoloDuo, Italy Poláčková, Czech Republic Gallén, Spain De Jonge, Canada North, England Powis, Australia Davin, USA Beattie, Canada Presented by UITARS NTERNATIONAL G I in cooperation with the GUITARSINT.COM CLEVELAND, OHIO USA 216-752-7502 Grey Fannel HAUTE COUTURE Fait Main en France • Hand Made in France www.bamcases.com Welcome Welcome to the sixteenth annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival. In pre- senting this event it has been my honor to work closely with Jason Vieaux, 2015 Grammy Award Winner and Cleveland Institute of Music Guitar Department Head; Colin Davin, recently appointed to the Cleveland Institute of Music’s Conservatory Guitar Faculty; and Tom Poore, a highly devoted guitar teacher and superb writer. Our reasons for presenting this Festival are fivefold: (1) to help increase the awareness and respect due artists whose exemplary work has enhanced our lives and the lives of others; (2) to entertain; (3) to educate; (4) to encourage deeper thought and discussion about how we listen to, perform, and evaluate fine music; and, most important, (5) to help facilitate heightened moments of human awareness. In our experience participation in the live performance of fine music is potentially one of the highest social ends towards which we can aspire as performers, music students, and audience members. For it is in live, heightened moments of musical magic—when time stops and egos dissolve—that often we are made most conscious of our shared humanity. Armin Kelly, Founder and Artistic Director Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival Acknowledgements We wish to thank the following for their generous support of this event: The Cleveland Institute of Music: Gary Hanson, Interim President; Lori Wright, Director, Concerts and Events; Marjorie Gold, Concert Production Manager; Gina Rendall, Concert Facilities Coordinator; Susan Iler, Director of Marketing and Communications; Lynn M. -

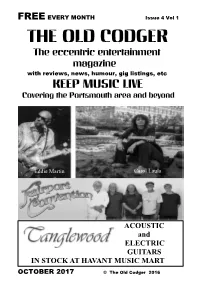

The Old Codger July 17

FREE EVERY MONTH Issue 4 Vol 1 THE OLD CODGER The eccentric entertainment magazine with reviews, news, humour, gig listings, etc KEEP MUSIC LIVE Covering the Portsmouth area and beyond Eddie Martin Carol Laula ACOUSTIC and ELECTRIC GUITARS IN STOCK AT HAVANT MUSIC MART OCTOBER 2017 © The Old Codger 2016 FREE EVERY MONTH The Old Codger Issue 4 Vol 1 OCTOBERS LIVE MUSIC EVERY SUNDAY @ 3.00 pm see gig listing for details 54 Bedhampton Road EVERY WEDNESDAY Havant PO9 3EY OPEN MIC NIGHT 8.30 pm * FIRST SATURDAY of month LIVE MUSIC @ 8.30 pm For more information on our live music and events go to - facebook.com/thegoldiehavant CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR EVENTS - ask at the bar THE MASSALA LOUNGE at The Golden Lion Phone 02392 481 590 TAKE AWAY / FREE LOCAL DELIVERY ON THE FRONT COVER appearing on the 20th October at The Eddie Martin appearing at The Spring, Emsworth Baptist Church, Emsworth. East Street, Havant on November 18th in his For tickets and other information - show ‘Up Close’ with ‘The Eddie Martin Trio’ phone 01243 370 501 who is one of Britain’s finest blues musi- COMING UP IN NOVEMBER cians. Monday November 6th appearing @ The For more info check with The Spring. Havant Music Club “Yeehaa Granma” com- ‘Carol Laula’ who rose to fame in 1990 bining bluegrass with skiffle band style, who when her song ‘Standing Proud’ was picked are a ragtaggle band of misfits with a suit- to represent Glasgow when it was chosen case, wash tub bass, washboard, guitar, as City of Culture. -

Creating Excitement for Materials Engineering and Science in Engineering Technology Programs

AC 2007-297: THE SOUND OF MATERIALS: CREATING EXCITEMENT FOR MATERIALS ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY PROGRAMS Kathleen Kitto, Western Washington University Kathleen L. Kitto is the Associate Dean for the new College of Sciences and Technology at Western Washington University. Previously, she was Associate Dean for the College of Arts and Sciences and served as Chair of Engineering Technology Department from 1995-2002. Since arriving at Western Washington University in 1988, her primary teaching assignments have been in the Manufacturing Engineering Technology program and in the development of the communication skills of engineering technology students; her research interests have been in the materials science of musical instruments, development of concurrent engineering curricula, development of devices for the differently-abled and in finite element analysis of complex components. She is keenly interested in enhancing the diversity of the students studying in the sciences, mathematics and technology. She received both her MS and BS degrees from the University of Montana/Montana Tech and previously worked for many years in industry primarily developing instrumentation systems and advanced materials. Page 12.1469.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2007 The Sound of Materials: Creating Excitement for Materials Engineering and Science in Engineering Technology Programs Abstract During the past four years the materials engineering aspects of musical instrument design have been incorporated into our Introductory Materials Engineering course to excite students about materials engineering and science and to help them understand various complex behaviors of materials, such as anisotropic properties or specific stiffness, through familiar, practical applications. The answer to a seemingly simple question about why a Stradivarius violin sounds the way it does is found more in complex materials properties than in many other basic design constraints such as geometry. -

On STAGE Series Carter and Beyond: Invention and Inspiration

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players on STAGE Series Carter and Beyond: Invention and Inspiration CARTER CHODOS SCHROEDER OCT 20, 2018 Taube Atrium Theater San Francisco, CA This event is San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Adam Luftman, trumpet Chris Froh, percussion David Tanenbaum, guitar Hannah Addario-Berry, cello Hrabba Atladottir, violin Jeff Anderle, clarinet Karen Gottlieb, harp Kate Campbell, piano Kyle Bruckmann, oboe The San Francisco Contemporary Music Players (SFCMP), a 24-member ensemble Loren Mach, percussion of highly skilled musicians, performs innovative contemporary classical music Meena Bhasin, viola based out of the San Francisco Bay Area. Nanci Severance, viola Nick Woodbury, percussion SFCMP aims to nourish the creation and dissemination of new works through Peter Josheff, clarinet high-quality musical performances, commissions, education and community Peter Wahrhaftig, tuba outreach. SFCMP promotes the music of composers from across cultures Richard Worn, contrabass and stylistic traditions who are creating a vast and vital 21st-century musical language. SFCMP seeks to share these experiences with as many people as Roy Malan, violin possible, both in and outside of traditional concert settings. Sarah Rathke, oboe Stephen Harrison, cello SFCMP evolved out of Bring Your Own Pillow concerts started in 1971 by Susan Freier, violin Charles Boone. Three years later, it was incorporated by Jean-Louis LeRoux and Tod Brody, flute Marcella DeCray who became its directors. Across its history, SFCMP has been led William