The Origin and Spread of Aboriginal Pidgin English In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 31, June 2019

From the President I recently experienced a great sense of history and admiration for early Spanish and Portuguese navigators during visits to historic sites in Spain and Portugal. For example, the Barcelona Maritime Museum, housed in a ship yard dating from the 13th century and nearby towering Christopher Columbus column. In Lisbon the ‘Monument to the Discoveries’ reminds you of the achievements of great explorers who played a major role in Portugal's age of discovery and building its empire. Many great navigators including; Vasco da Gama, Magellan and Prince Henry the Navigator are commemorated. Similarly, in Gibraltar you are surrounded by military and naval heritage. Gibraltar was the port to which the badly damaged HMS Victory and Lord Nelson’s body were brought following the Battle of Trafalgar fought less than 100 miles to the west. This experience was also a reminder of the exploits of early voyages of discovery around Australia. Matthew Flinders, to whom Australians owe a debt of gratitude features in the June edition of the Naval Historical Review. The Review, with its assessment of this great navigator will be mailed to members in early June. Matthew Flinders grave was recently discovered during redevelopment work on Euston Station in London. Similarly, this edition of Call the Hands focuses on matters connected to Lieutenant Phillip Parker King RN and his ship, His Majesty’s Cutter (HMC) Mermaid which explored north west Australia in 1818. The well-known indigenous character Bungaree who lived in the Port Jackson area at the time accompanied Parker on this voyage. Other stories in this edition are inspired by more recent events such as the keel laying ceremony for the first Arafura Class patrol boat attended by the Chief of Navy. -

Letters Patent Erecting Colony of Queensland 6 June 1859 (UK

[BEGIN TRANSCRIPTION] (21.) Letters Patent erecting Moreton Bay into a Colony under the name of Queensland and appointing Sir George Ferguson Bowen K C M G to be Captain General and Governor in Chief of the same Victoria by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Queen Defender of the Faith To Our trusty and well beloved Sir George Ferguson Bowen Knight Commander of Our most distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George Greeting Whereas by a reserved Bill of the Legislature of New South Wales passed in the seventeenth year of our Reign as amended by an Act passed in the Session of Parliament holden in the eighteenth and nineteenth years of Our Reign entitled “An Act to enable Her Majesty to assent to a Bill as amended of the Legislature of New South Wales to confer a Constitution on New South Wales and to grant a Civil List to Her Majesty” it was enacted that nothing therein contained should be deemed to prevent Us from altering the boundary of the colony of New South Wales on the north in such manner as to us might seem fit And it was further enacted by the said last recited Act that if we should at any time exercise the power given to us by the said reserved Bill of altering the northern boundary of our said Colony it should be lawful for us by any Letters Patent to be from time to time issued under the Great Seal of our United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to erect into a separate colony or colonies any territories which might be separated from our said colony of New South Wales by such alterations -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

A Short History of Thuringowa

its 0#4, Wdkri Xdor# of fhurrngoraa Published by Thuringowa City Council P.O. Box 86, Thuringowa Central Queensland, 4817 Published October, 2000 Copyright The City of Thuringowa This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. All rights reserved. ISBN: 0 9577 305 3 5 kk THE CITY of Centenary of Federation i HURINGOWA Queensland This publication is a project initiated and funded by the City of Thuringowa This project is financially assisted by the Queensland Government, through the Queensland Community Assistance Program of the Centenary of Federation Queensland Cover photograph: Ted Gleeson crossing the Bohle. Gleeson Collection, Thuringowa Conienis Forward 5 Setting the Scene 7 Making the Land 8 The First People 10 People from the Sea 12 James Morrill 15 Farmers 17 Taking the Land 20 A Port for Thuringowa 21 Travellers 23 Miners 25 The Great Northern Railway 28 Growth of a Community 30 Closer Settlement 32 Towns 34 Sugar 36 New Industries 39 Empires 43 We can be our country 45 Federation 46 War in Europe 48 Depression 51 War in the North 55 The Americans Arrive 57 Prosperous Times 63 A great city 65 Bibliography 69 Index 74 Photograph Index 78 gOrtvard To celebrate our nations Centenary, and the various Thuringowan communities' contribution to our sense of nation, this book was commissioned. Two previous council publications, Thuringowa Past and Present and It Was a Different Town have been modest, yet tantalising introductions to facets of our past. -

(AWU) and the Labour Movement in Queensland from 1913-1957

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957 Craig Clothier University of Wollongong Clothier, Craig, A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1996 This paper is posted at Research Online. Introduction Between 1913-1957 the Queensland Branch of the Australian Workers' Union (AWU) was the largest branch of the largest trade union in Australia. Throughout this period in Queensland the AWU accounted for approximately one third of all trade unionists in that state and at its peak claimed a membership in excess of 60 000. Consequenfly the AWU in Queensland was able to exert enormous influence over the labour movement in that state not only in industrial relations but also within the political sphere through its affiliation to the Australian Labor Party. From 1915-1957 the Labor Party in Queensland held office for all but the three years between 1929-1932. AWU officials and members dominated the Labor Cabinets of the period and of the eight Labor premiers five were members of the AWU, with two others closely aligned to the Union. Only the last Labor premier of the period, Vincent Clare Gair, owed no allegiance to the AWU. The AWU also used its numerical strength and political influence to dominate the other major decision-making bodies of Queensland's labour movement, most notably the Queensland Central Executive (QCE), that body's 'inner' Executive and the triennial Labor-in-Politics Convention. -

The Pounding of Rockhampton the Archer Brothers

The Pounding of Rockhampton and The Archer Brothers. BY WILLIAM CLARK. {Mead at a Meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, on October 12'th, 1917.) Of all the great maritime ports of entry in north-eastern Australia, the Port of Rockhampton is by far the most important, possessing a wonderful endowment of back country, rich in sources of mineral wealth and in fertile soil, its natural pasturage even surpassing the artifical cultured conditions of the meadow lands of older countries. On the fine black soil downs of Springsure and CuJlin-la- ringo, Fernlees and the Minerva country, the growth of the tussock grass, sheep fescues, wild carrot, wild eschalots, wild lucerne, wild melons and innumerable flowering herbs attest the truth of the statement here made. This immense tract of country is traversed and drained by no less than seven watersheds, forming the course of the Dawson*, Nogoa, Comet, Claude, Barcoof, Nive arid Thompson^ Rivers. Its great westerly range system, known as the Great Divide, turns its easterly waters into the Mackenzie**, which, with its affluent, the Isaacf f river, rolls down to the " Lordly Fitzroy," with its ocean gates at Keppel Bay, while the waters flowing from the Great * Discovered by Leichhardt, 5th November, 1844, and naiaed by him after R. B. Dawson, of Black River, afterwards of Casino. t Discovered by Sir Thomas Mitchell, 13th September, 1845, and named the " Victoria "—" the future highway to the Indian- Ocisan." In August, 1847, E. B. Kennedy proved it to be the Cooper's Creek of Sttirt. Sabisequentiy called the Bareoo. -

Macquarie University Researchonline

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author’s version of an article from the following conference: Walsh, Robin (2008) Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co- operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Digital discoveries : strategies and solutions : 29th annual conference of the Association of Technological University Libraries, (21 - 24 April 2008, Auckland) Access to the published version: http://www.iatul.org/doclibrary/public/Conf_Proceedings/2008/RWalsh 080318.doc Title Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co-operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Author Robin Walsh Macquarie University Library Sydney NSW 2109 Australia Contact Details [email protected] www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema Abstract The efforts of libraries and archival institutions in collecting and curating dispersed collections of original letters, journals, pictorial sources, and realia/artefacts are essential contributions towards research and scholarship. Recent technological advances in digitization offer important new possibilities in the reproduction of documents and images as well as enhanced access to dispersed institutional holdings. The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive (LEMA) is a co-operative inter-institutional website project based at Macquarie University Library, in partnership with key Australian and UK institutions. The aim of the LEMA Project is to create a digital research gateway to the writings of the Lachlan Macquarie (1761-1824), governor of New South Wales from 1810- 1821 and his wife Elizabeth (1778-1835), and thereby assist in the study and analysis of their place in Australian and imperial history. The LEMA framework is designed to explore the personal and global contexts of the Macquaries through the use of full-text transcriptions of documentary sources, as well as contributing towards the identification and digital repatriation of personal objects associated with their lives. -

Australian Studies Journal 31/2017

Im Namen der Gesellschaft für Published on behalf of the Australienstudien herausgegeben Association for Australian Studies von by Henriette von Holleuffer, Hamburg, Germany – [email protected] Oliver Haag, The University of Edinburgh, School of History Classics and Archaeology, Teviot Place, EH8 9AG, UK – [email protected] Bitte senden Sie alle Korrespondenz und Manu- Please send all correspondence and manuscripts skripte an die Herausgeber. Manuskripte, die an- to the editors. Manuscripts that have been pub- derswo erschienen sind, werden nur nach Rück- lished elsewhere will, in special cases, be consid- sprache zur Veröffentlichung angenommen. Eine ered for publication. A republication elsewhere is nachträgliche, anderweitige Veröffentlichung ist possible upon prior consultation with the editors. It nach Rücksprache mit dem Herausgeber möglich, is expected that the subsequent publication carries wobei ein Verweis auf dieses Organ erwartet wird. a reference to this periodical. Contributions to this journal are fully refereed by members of the ZfA | ASJ Advisory Board: Rudolf Bader, PH Zurich l Elisabeth Bähr, Speyer l Jillian Barnes, University of Newcastle l Nicholas Birns, Eugene Lang College, New York City l Boris Braun, University of Cologne l David Callahan, Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal l Maryrose Casey, Monash University l Ann Curthoys, University of Sydney l Brian Dibble, University of Western Australia (em.) | Corinna Erckenbrecht, Cologne/Görlitz l Gerhard Fischer, University of New South Wales l Victoria Grieves, -

Evolution of the Ipswich Railway Workshops Site

VOLUME 5 PART 1 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM – CULTURE © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum), 2011 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Qld Australia Phone 61 7 3840 7555 Fax 61 7 3846 1226 www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site http://www.qm.qld.gov.au/About+Us/Publications/Memoirs+of+the+Queensland+Museum A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum Evolution of the Ipswich Railway Workshops site Robyn BUCHANAN Buchanan, R. 2011 Evolution of the Ipswich Railway Workshops Site. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture 5(1): 31-52. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788 The decision to build the first railway in Queensland from Ipswich to the Darling Downs meant that railway workshops were required at Ipswich. The development of the Ipswich Railway Workshops site began with the original Ipwich Workshops site of 1864 which was adjacent to the Bremer River at North Ipswich. The first two major workshop buildings were iron and zinc structures imported from England in pre-fabricated form. Over the next few years, additional buildings including a brick store were constructed by local contractors. -

Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame

INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC REVIEW VoL. 2 No. 1 {NEW SERIES) JUNE 2001 Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame joe Doyle Since his death many books and articles have been written about Matthew Flinders . During his life, apart from his own books, he wrote much himself, and there is a large body of contemporary correspondence concerning him in various archives in England and Australia. The bicentenary of the start of his voyage in Investigator is so important that it deserves once more, to be drawn to the atten tion of those interested in hydrography. This paper traces Matthew Flinders' early life and training as a hydrographer until July 1801 when he sailed from England in Investigator on his fateful mission to chart the little known southern continent, that land mass which had yet to be named Australia. Introduction An niversaries of two milestones of 'European ' Austral ia occur in 2001. The sig nificant event is the centenary of the formation of the Commonwealth of Australi a. It is also the bicentenary of the start of an important British voyage to complete the survey of that continent and from which the term Australia began to be accept ed as the name for the country. July 2001 is the 200th anniversary of the departure from Spithead of Investigator, a sloop' fitted out and stored for a voyage to remote parts. The vessel, under the command of Commander Matthew Flinders, Royal Navy, was bound for New South Wales, a colony established thirteen years earlier. The purpose of the voyage was to make a complete examination and survey of the coast of that island continent. -

FITZROY WATERS from Sheep to Cattle and Coal

158 FITZROY WATERS From Sheep to Cattle and Coal (Written by Archibald Archer and read by him before the Royal Historical Society of Queensland at Newstead House on 24 August 1972.) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Your President, Mr. Norman Pixley, has honoured me with a request to read a paper to you tonight. If I talk too much about the Archers, it is because I have access to their letters and journals which have survived them. If I quote too much from their writings, it is because they can tell their own tales so much better than I. I have used the Archer letters, the Durundur Journal, Colin Archer's Journal, Thomas Archer's Recollections, Roy Connolly's Southern Saga. Finally, I want to thank my late cousin and brother-in-law Alister Archer for his work as the family historian. Were it not for his patient research into the writings of his father and uncles the preparation of this paper would have been far more difficult. INTRODUCTORY The old timer took a long pull at his glass before continu ing. "It's been a terrible dry spring, Archie. The sheep will pull through on the windfalls but the cattle look woeful." He tossed off what was left in his glass and set it back on the bar counter. I caught the barman's eye. Thirstily we watched him set up again the three frosty glasses with their trim white collars. We were chatting in the only pub in the tiny railway town halfway between Rockhampton and Longreach. Not much of a place, though the station people and the gem-diggers called it "town". -

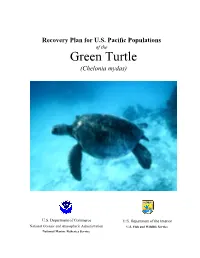

Recovery Plan for the US Populations of the Green Turtle

Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of the Interior National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Marine Fisheries Service Cover Photograph Courtesy of George Balazs Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect the species. Plans are prepared by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies and others. Objectives will only be attained and funds expended contingently upon appropriations, priorities and other budgetary constraints. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approvals of any individuals or agencies, other than those of NMFS and the FWS which were involved in the plan formulation. They represent the official positions of NMFS and the FWS only after they have been approved by the Assistant Administrator for Fisheries or the Regional Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citations should read as follows: National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. Additional copies of this plan may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Reference Service 5430 Grosvenor Lane Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 (301)492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 The fee for the plan varies depending on the number of pages of the plan.