Rifles for Watie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

February 2003, Vol. 29 No. 1

Contents Letters: York’s medicine; short-haired strangers; Missouri’s source 2 From the Directors: New endowment program 5 From the Bicentennial Council: Honoring Nez Perce envoys 6 Trail Notes: Trail managers cope with crowds 8 Reliving the Adventures of Meriwether Lewis 11 The explorer’s biographer explains his special attachment to “the man with whom I’d most like to sit around the campfire” By Stephen E. Ambrose The “Odyssey” of Lewis and Clark 14 A look at the Corps of Discovery through the eyes of Homer Rabbit Skin Leggings, p. 6 By Robert R. Hunt The Big 10 22 What were the essential events of the Lewis & Clark Expedition? By Arlen J. Large Hunt on Corvus Creek 26 A primer on the care and operation of flintlock rifles as practiced by the Corps of Discovery By Gary Peterson Reviews 32 Jefferson’s maps; Eclipse; paperback Moulton In Brief: Before Lewis and Clark; L&C in Illinois Clark meets the Shoshones, p. 24 Passages 37 Stephen E. Ambrose; Edward C. Carter L&C Roundup 38 River Dubois center; Clark’s Mountain; Jefferson in space Soundings 44 From Julia’s Kitchen By James J. Holmberg On the cover Michael Haynes’s portrait of Meriwether Lewis shows the captain holding his trusty espontoon, a symbol of rank that also appears in Charles Fritz’s painting on pages 22-23 of Lewis at the Great Falls. We also used Haynes’s portrait to help illustrate Robert R. Hunt’s article, beginning on page 14, about parallels between the L&C Expedition and Homer’s Odyssey. -

Newbery Medal Winners, 1922 – Present

Association for Library Service to Children Newbery Medal Winners, 1922 – Present 2019: Merci Suárez Changes Gears, written by Meg Medina (Candlewick Press) 2018: Hello, Universe, written by Erin Entrada Kelly (Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) 2017: The Girl Who Drank the Moon by Kelly Barnhill (Algonquin Young Readers/Workman) 2016: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña (G.P. Putnam's Sons/Penguin) 2015: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) 2014: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) 2013: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate (HarperCollins Children's Books) 2012: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos (Farrar Straus Giroux) 2011: Moon over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool (Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children's Books) 2010: When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead, published by Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books. 2009: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman, illus. by Dave McKean (HarperCollins Children’s Books) 2008: Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schlitz (Candlewick) 2007: The Higher Power of Lucky by Susan Patron, illus. by Matt Phelan (Simon & Schuster/Richard Jackson) 2006: Criss Cross by Lynne Rae Perkins (Greenwillow Books/HarperCollins) 2005: Kira-Kira by Cynthia Kadohata (Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster) 2004: The Tale of Despereaux: Being the Story of a Mouse, a Princess, Some Soup, and a Spool of Thread by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) 2003: Crispin: The Cross of Lead by Avi (Hyperion Books for Children) 2002: A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park(Clarion Books/Houghton Mifflin) 2001: A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck (Dial) 2000: Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis (Delacorte) 1999: Holes by Louis Sachar (Frances Foster) 1998: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse (Scholastic) 1997: The View from Saturday by E.L. -

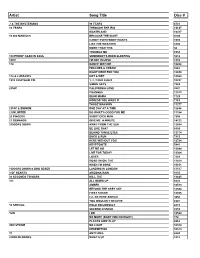

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Newbery Medal Award Winners

Author Title Year Keller, Tae When You Trap a Tiger 2021 - Winner Craft, Jerry New Kid 2020 - Winner Medina, Meg Merci Suárez Changes Gears 2019 - Winner Kelly, Erin Entrada Hello, Universe 2018 - Winner The Girl Who Drank the Moon The Girl Who Drank the Moon 2017 - Winner Last Stop on Market Street Last Stop on Market Street 2016 - Winner The Crossover The Crossover 2015 - Winner Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures 2014 - Winner The One and Only Ivan The One and Only Ivan 2013 - Winner Gantos, Jack Dead End in Norvelt 2012 - Winner Vanderpool, Clare Moon Over Manifest 2011 - Winner Stead, Rebecca When You Reach Me 2010 - Winner Gaiman, Neil The Graveyard Book 2009 - Winner Schlitz, Laura Amy Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village 2008 - Winner Patron, Susan The Higher Power of Lucky 2007 - Winner Perkins, Lynne Rae Criss Cross 2006 - Winner Kadohata, Cynthia Kira-Kira 2005 - Winner The Tale of Despereaux: Being the Story of a Mouse, a Princess, DiCamillo, Kate Some Soup, and a Spool of Thread 2004 - Winner Avi Crispin: The Cross of Lead 2003 - Winner Park, Linda Sue A Single Shard 2002 - Winner Peck, Richard A Year Down Yonder 2001 - Winner Curtis, Christopher Paul Bud, Not Buddy 2000 - Winner Sachar, Louis Holes 1999 - Winner Hesse, Karen Out of the Dust 1998 - Winner Konigsburg, E. L. The View from Saturday 1997 - Winner Cushman, Karen The Midwife's Apprentice 1996 - Winner Creech, Sharon Walk Two Moons 1995 - Winner Lowry, Lois The Giver 1994 - Winner Rylant, Cynthia Missing May 1993 - Winner Reynolds Naylor, Phyllis Shiloh 1992 - Winner Spinelli, Jerry Maniac Magee 1991 - Winner Lowry, Lois Number the Stars 1990 - Winner Fleischman, Paul Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices 1989 - Winner Freedman, Russell Lincoln: A Photobiography 1988 - Winner Fleischman, Sid The Whipping Boy 1987 - Winner MacLachlan, Patricia Sarah, Plain and Tall 1986 - Winner McKinley, Robin The Hero and the Crown 1985 - Winner Cleary, Beverly Dear Mr. -

The Famuan: October 2, 1986

This year, the Inde' owling team has as Coll. 0 :;a s heart set on NEWS ringing home the i ampionship. CAMPUS NOTES VSports 8 CLASSIFIEDS The Fal HEALTH THEVOCE*F LOIAAMUIEST 'an OPINIONS SPORTS VOL. 92 No. 15 / TALLAHASSEE, FLA. www.thefam an.com LIFESTYLES 9-12 - OCTOBER 23, 2000 - It's time FAMU defense saves the day By Andre Carter special teams units provided the Correspondent spark the struggling Rattlers needed again to after two straight losses. Florida A&M University radio The defense played a role in 28 of color commentator Mike Thomas the 42 points, including two defen- summed up FAMU's game against sive touchdowns. Turnovers set up represent the Norfolk State Spartans in 12 two more scores. They were seeking words. redemption after allowing 30 points "This has been a dominating per- versus North Carolina A&T last formance so far by this defensive week. They showed the same inten- unit," Thomas said during the first sity their coaches showed on the half. sidelines. In front of what was characterized After both teams started the game as a sparse crowd at Dick Price with three and outs of offense, cor- Stadium, FAMU defeated the nerback Troy Hart intercepted ANTOINE DAVIS Spartans 42-14. The Rattlers' record Spartan quarterback John Roberts moves to 6-2 overall and 5-1 in the and returned the ball to the Norfolk The Famuan/ Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference. State 5-yard line. Two plays later, Kea Dupree Editor's note: This column is While the offense started and stalled FAMU redeemed it's loss against the Aggies (above) with a running in the absence of SGA early in the game, the defense and Please see Game/ 8 42-14 victory over the Norfolk Spartans on Saturday. -

Fticrilty, Students. Ajld Commu~ Uniteagainstabolishing Open Atlm, Ibsionb

;.~':.. \ , ...... .' .... .. -- . ..... ~ r ..:. - ." ,. J l, -..... - . .. -: .'.. ' "_ ", •.•• 0.; •. ....., "" .. ,.. ..- .' .. ... _.~ "'...- - '-," .-. -•... -' ..'. ..... ,, ........ -, By Chan-joo.Moon ....... ;.. ' ..CollegePr-esident Matthew Goldste" will1 :v 'B' chCoP;"'':>""~~~' . ". ,lIt. .r-r-zr-» ea.e "aJ:U... : , to become. theeighthpresidentof.". Adelphi:University-ef'teCtive,JUna <~ 15. -The,. official announcement, ' _:: came·at'a·press conference on the"'f mornm-g'ofMareh2 at the CamPUS -,,~~. ofAdelphi,'UniverSity in Long Is- '; .: land. ' '" ,"Iwas l~~iingan_in~tifutionthat':·:. I .care deeply abOuti,an··institution,,~, ,that.Ihelped mold' withhigh stan- .: ~,, dards'and a. sense.of,community," .;:~~~ saidGoldstein. "[Butltherecomes: -: a time when your best work has. " already.been.demonstrated,": ' ,~~,~~nceme~~ cpmesatthe heelsof'the departure ofVice~i- ,·BaF~·.~.~G01~;-·-.~,:'~"tm~L:I8enberg, dentJamesMUithB on January 16~ et».draran~8oIirdof:'f'jzq~Ade"'hi:~t;y·"'" '"" ProVo$lbis'8:-etoo'fiholm:m-ayfin(:}-'" 'Stateeompt~tter'H~~al'tMeCaH;""fs~be~g,-ehaitinan 'of-Adelphi herselr.in_eh~:of-anthreetop and,Jtf~~~ Tetreault,·.viee -,: UIli~ity:~_ ~f trustees.. He postscfBaroChCollege: president, ,' presidentfor academic affairS at ' saidthatGoldstein· had demon vice president'and'provost. .- californi,aState-UniversityatFul-strateda"acholar1y statute, a com- The·tWo-~.~caDdid&testorthe ._ ..lertOn. -, ' ,'..:'.. '- ,'. ' Dlitm~Ju,J1!!iensiti~,J;Q~stll- prt!.Si~oJ\A~elphi:~~~~ee:' ·..~w Goldstein. w8$"the -'~"8nd'WoU1dtakeA4e1Phiin- -

Ware It, Arm /Me Ain All II

Gavin Rocks Special Manchu, and many others have shown that the next generation has arrived. I can't wait to see all you freaks at the GAVIN Convention. Remember to catch' Snot and Fu Manchu Thursday night, and just ask Kreature or Gill for free Shout ut drinks. Mayhem/Fierce Recordings Rose Victim. Make sure to eat your greens rock! "We wanted the future, we Kevin "Chainsaw" This being the first hard x203 and realize your potential. have it." (212) 226-7272 rock/metal special of the year, [email protected] we thought it appropriate to Columbia Records F.A.D. Records hope ei eryone had a great holiday; mine was a blur. Wake up, eat, shower, offer hard rock promotion peo- Benjamin Berkman Paula Kopka (212) 833-5118 (818) 752-8799 go out, drink, return home (with any ple an opportunity to reintro- [email protected] noisela@noisere- luck) around 6 a.m., pass out, wake up about 4 p.m., repeat. I actually had it themselves and shame- Greetings to all. 1.111 really excited to he cords.com duce that way. But now we are apart of Columbia's re-entry into the Well the new year is scheduled lessly promote their priority back to the grind and I have got loads world of metal! Yes, it is true; we signed here, and I'm back to of incredible music for you! You've projects. You'llfind out who's Clutch, and with your help and support, drive you guys even already received Pro -Pain, next is Union we're going to make this band happen. -

Early English Firearms: a Re-Examination of the Evidence

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 Early English Firearms: A Re-examination of the Evidence Beverly Ann Straube College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Straube, Beverly Ann, "Early English Firearms: A Re-examination of the Evidence" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625569. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-x5sp-x519 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EARLY ENGLISH FIREARMS: A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE EVIDENCE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Beverly A. Straube 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts A . — Author Approved, August Tames D. Lavin Department of Modern Languages Barbara G./ Carson Jay Gayn<tor The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation DEDICATION To my British parents Edwyn and Ruth Hardy who are amused and pleased that their American-born daughter should be digging up and studying the material remains of her English forebears. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .............................................. V ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..... ............................... vii LIST OF FIGURES ....................................... ix ABSTRACT ............................................. xii INTRODUCTION ......................................... -

Rifles for Watie Harold Keith

TEACHER GUIDE GRADES 6-8 COMPREHENSIVE CURRICULUM BASED LESSON PLANS Rifles for Watie Harold Keith READ, WRITE, THINK, DISCUSS AND CONNECT Rifles for Watie Harold Keith TEACHER GUIDE NOTE: The trade book edition of the novel used to prepare this guide is found in the Novel Units catalog and on the Novel Units website. Using other editions may have varied page references. Please note: We have assigned Interest Levels based on our knowledge of the themes and ideas of the books included in the Novel Units sets, however, please assess the appropriateness of this novel or trade book for the age level and maturity of your students prior to reading with them. You know your students best! ISBN 978-1-50204-122-7 Copyright infringement is a violation of Federal Law. © 2020 by Novel Units, Inc., St. Louis, MO. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or To order, contact your transmitted in any way or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, local school supply store, or: recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from Novel Units, Inc. Toll-Free Fax: 877.716.7272 Reproduction of any part of this publication for an entire school or for a school Phone: 888.650.4224 system, by for-profit institutions and tutoring centers, or for commercial sale is 3901 Union Blvd., Suite 155 strictly prohibited. St. Louis, MO 63115 Novel Units is a registered trademark of Conn Education. [email protected] Printed in the United States of America. novelunits.com Table of -

The Morean Arts Center's 100Th Anniversary

JULY / 2017 ISSUE 45 The Morean Arts Center’s 100th Anniversary he Morean Arts Center, the first arts center south of Atlanta, is turning 100! Drawing inspiration from the past 100 years, the Morean has created and enhanced a variety of offerings to the community in the form of master artist workshops, elevated Tevents, classes in a variety of mediums, hands-on programs and the opening of the new garden space at the Chihuly Collection now located at 720 Central Avenue. The Morean Arts Center’s story started in the early 20th century when a group of local artists in need of a place to work, teach and display their art connected with the Florida Winter Art School. The Art Club of St. Petersburg – the first art gallery south of Atlanta – settled into space provided by the Florida Art School in their building on Beach Drive. As St. Petersburg and surrounding areas grew, so did the Morean Arts Center from its informal beginnings in 1917, to become an integral part of the country’s top arts destinations. After several relocations and name changes, the Morean Arts Center settled at its current location on Central Avenue. Today, the Morean offers programs for all mediums, styles, skill levels and ages housed in four locations in downtown St. Petersburg. The locations include the Morean Arts Center, Chihuly Collection, Morean Glass Studio & Hot Shop and Morean Center for Clay. At the end of a century of steady growth, the Morean Arts Center continues to provide a place for the arts in St. Petersburg. Staff, board members, artists, teachers and volunteers have witnessed the Morean Arts Center grow and become an institution where one can explore creativity and push boundaries. -

312287 Leaders

Glossary anchor <) holding the string at full draw; @) position of the string+ fingers+ hand+ or mechanical release at full draw (see also high anchor and low anchor) barrel the tube that contains and directs the projectile (see also bore+ chamber+ rifling+ muzzle) bolt <) moveable locking device that seals a cartridge in the chamber of a firearm+ usually contains the firing pin and a means of extracting cartridges from the chamber; @) a quarrel or arrow for a crossbow; B) a threaded rod used as a connector butt <) shoulder end of a rifle or shotgun stock; @) target backing device designed to stop and hold arrows without damage+ may be made of foam blocks or baled materials like paper+ straw+ excelsior+ sugar cane fiber+ marsh grass or plastic foam; B) a shooting stand or blind centerfire a firearm using a primer or battery cup located in the center of the cartridge head compound bow bow designed to give the shooter a mechanical advantage during the draw+ changing the shape of the draw force curve and yielding a higher efficiency in energy transfer to the arrow draw <) process of pulling the string back to the anchor point; @) type of anchoring system used (such as Apache draw+ high draw+ low draw) cf% “anchor” fletching feathers or vanes used to steer and stabilize the flight of an arrow flint extremely hard stone used in flintlock firearms and arrowheads flintlock <) lock used on flintlock firearms+ featuring a cock+ flint+ frizzen and flash pan; @) firearm using a flintandsteel lock 24 fluflu specialized arrow designed for