Center for Humane Technology | Your Undivided Attention Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

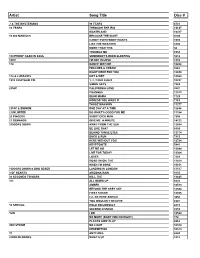

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Methamphetamine & Opioid Response Initiative

Billings Metro VISTA Project Methamphetamine & Opioid Response Initiative: A Community Assessment July 2019 AmeriCorps VISTAs: Nick Fonte and Amy Trad Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Area of Study ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Section 2: Methamphetamine vs. Opioids ................................................................................................................. 5 KEY STAKEHOLDERS ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Section 1: Community Organizations/Non-profits .................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Statewide and Local Initiatives ................................................................................................................ 9 RELEVANT DATA ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Section 1: Methamphetamine and Opioids in the News ......................................................................................... -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Egypt and the Middle East

Monitoring Study: British Media Portrayals of Egypt Author: Guy Gabriel - AMW adviser Contact details: Tel: 07815 747 729 E-mail: [email protected] Newspapers monitored: All British national daily broadsheets and tabloids, as well as the Evening Standard Monitoring period: May 2008 - May 2009 1 Table of contents: Egypt & the Middle East Regional Importance Israel Camp David Accords The Gulf Sudan Horn of Africa Diplomacy towards Palestine Before Gaza Conflict 2009 Gaza 2009 Diplomacy The Palestine Border Tunnel Economy Crossing Closures Domestic Egypt Food Religion in Society State Ideology Economy Miscellaneous Domestic Threats Emergency Rule & Internal Security Terrorism Egypt & the West Egypt as an Ally 'War on Terror' Suez Ancient Egypt Influence of Egyptian Art Other Legacies Tourism 2 Egypt & the Middle East Regional Importance Various other Middle Eastern countries are sometimes mentioned in connection with Egypt's regional influence, though very rarely those from North Africa. In terms of Egypt's standing in the Middle East as viewed by the US, a meeting in Cairo, as well as Saudi Arabia and Israel, are "necessary step[s] in the careful path Mr Obama is laying out," notes Times chief foreign affairs commentator Bronwen Maddox (29 May 2009). A "solid" Arab-Israeli peace deal "must include President Mubarak of Egypt," says Michael Levy in the same newspaper (14 May 2009). Regarding a divided Lebanon, the Arab League is "tainted by the commitment of the Saudis and Egyptians to one side rather than the other," according to an Independent editorial (13 May 2008). Egypt appointing an ambassador to Iraq generates interest "not only because it is the most populous Arab country but also because its chargé d'affaires in Baghdad was kidnapped and killed in 2005," writes Guardian Middle East editor Ian Black (2 July 2008). -

This Is How It Ends Eva Dolan

FEBRUARY 2018 This Is How It Ends Eva Dolan Elegantly crafted, humane and thought-provoking. She 's top drawer ' Ian Rankin Description Elegantly crafted, humane and thought-provoking. She 's top drawer ' Ian Rankin This is how it begins. With a near-empty building, the inhabitants forced out of their homes by property developers. With two women: idealistic, impassioned blogger Ella and seasoned campaigner, Molly. With a body hidden in a lift shaft. But how will it end' About the Author Eva Dolan is an Essex-based copywriter and intermittently successful poker player. Shortlisted for the Crime Writers' Association Dagger for unpublished authors when she was just a teenager, the first four novels in the Zigic and Ferreira series, set in the Peterborough Hate Crimes Unit, have been published to widespread critical acclaim. Tell No Tales was shortlisted for the Theakston's Crime Novel of the Year Award and the third in the series, After You Die, was longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger. @eva_dolan Price: $27.99 (NZ$29.99) ISBN: 9781408886656 Format: Paperback Dimensions: mm Extent: 336 pages Main Category: FF Sub Category: FH Thriller / Suspense Illustrations: Previous Titles: Author now living: Bloomsbury FEBRUARY 2018 This Is How It Ends 8 Copy Pack Includes 8 copies of This Is How It Ends, plus free reading copy Description About the Author Price: $223.92 (NZ$239.92) ISBN: 9781408875919 Format: Dimensions: mm Extent: 0 pages Main Category: WZ Sub Category: Illustrations: Previous Titles: Author now living: Bloomsbury FEBRUARY 2018 Peach Emma Glass 'An immensely talented young writer' George Saunders Description 'An immensely talented young writer' George Saunders Slip the pin through the skin. -

Understanding the Neuroscience of Addiction to Provide Effective Treatment PDH Academy Course #9641 (6 CE HOURS)

CONTINUING EDUCATION for Social Workers Understanding the Neuroscience of Addiction to Provide Effective Treatment PDH Academy Course #9641 (6 CE HOURS) Biographical Summary Jessica Holton, MSW, LCSW, LCAS has nearly two decades of experience and is a private practitioner specializing in treating Trauma & Stress Related Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, and Addictions. She earned her Master of Social Work and became certified in Social Work Practice with the Deaf and Hard of Hearing from East Carolina University. Jessica is active in leadership roles with the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) at the local, state, and national levels (Co-Chair of NASW-NC’s Greenville’s Local Program Unit from 2005-2012; Elected as NASW-NC’s President Elect (2011-2012) and NASW-NC’s President (2012-2014); Appointed to NASW’s Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug (ATOD) Specialty Section Committee as a committee member in 2008, then appointed as the Chair in 2010 to 2016, and recently returned to a committee member. Jessica is involved with Addiction Professionals of North Carolina, as well, in which she was elected as a Member At Large for a three year term (2017 to 2020). Jessica has written many professional newsletter articles, several peer-reviewed journal articles, and has presented nationwide at numerous conferences. She is passionate about learning, sharing her knowledge and elevating her profession. She also received the East Carolina University School of Social Work Rising Star Alumni Award in 2012, selected as The Daily Reflector’s Mixer Magazines30 under 30 in 2007, Wilson Resource Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Community Service Award in 2005 and the National Association for the Advancement of Educational Research Annual Conference Award for Service to the Profession 2002 Outstanding Researcher. -

Sarah Punshon Director

Sarah Punshon Director Sarah is founder and Artistic Director of One Tenth Human, collaborating with artists, scientists and children to create innovative arts-science adventures (“really great children’s theatre” Maddy Costa, Exeunt). One Tenth Human are currently developing projects for young audiences with Polka Theatre and Big Imaginations. Their most recent show, Arthur, was a solo-and-a-half show performed by Daniel Bye and his 4 month old baby, and won a Scotsman Fringe First 2019. Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes CURIOUS INVESTIGATORS One Tenth Human Commissioned by Big Imaginations CINDERELLA: THE AWESOME Polka Theatre / One By Sarah Punshon and Felix Hagan, TRUTH Tenth Human created with Toni-Dee Paul THE JUNGLE BOOK Oldham Coliseum Written by Jessica Swale based on the book by Rudyard Kipling Directed by Sarah Punshon Theatre Production Company Notes ARTHUR Edinburgh Festival Co-created with Daniel Bye 2019 *Winner: Scotsman Fringe First United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes CINDERELLA: A The Dukes Lancaster Devised by Sally Cookson, Adam Peck and FAIRYTALE Company 2019 PETER PAN The Dukes Lancaster By JM Barrie 2018 Adapted by Sarah Punshon THE THREE MUSKETEERS The Dukes Lancaster & By Hattie Naylor 2018 Williamson Park *Nominated for the UK Theatre Award for Best Production for Children and Young People EDUCATING -

The Famuan: October 2, 1986

This year, the Inde' owling team has as Coll. 0 :;a s heart set on NEWS ringing home the i ampionship. CAMPUS NOTES VSports 8 CLASSIFIEDS The Fal HEALTH THEVOCE*F LOIAAMUIEST 'an OPINIONS SPORTS VOL. 92 No. 15 / TALLAHASSEE, FLA. www.thefam an.com LIFESTYLES 9-12 - OCTOBER 23, 2000 - It's time FAMU defense saves the day By Andre Carter special teams units provided the Correspondent spark the struggling Rattlers needed again to after two straight losses. Florida A&M University radio The defense played a role in 28 of color commentator Mike Thomas the 42 points, including two defen- summed up FAMU's game against sive touchdowns. Turnovers set up represent the Norfolk State Spartans in 12 two more scores. They were seeking words. redemption after allowing 30 points "This has been a dominating per- versus North Carolina A&T last formance so far by this defensive week. They showed the same inten- unit," Thomas said during the first sity their coaches showed on the half. sidelines. In front of what was characterized After both teams started the game as a sparse crowd at Dick Price with three and outs of offense, cor- Stadium, FAMU defeated the nerback Troy Hart intercepted ANTOINE DAVIS Spartans 42-14. The Rattlers' record Spartan quarterback John Roberts moves to 6-2 overall and 5-1 in the and returned the ball to the Norfolk The Famuan/ Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference. State 5-yard line. Two plays later, Kea Dupree Editor's note: This column is While the offense started and stalled FAMU redeemed it's loss against the Aggies (above) with a running in the absence of SGA early in the game, the defense and Please see Game/ 8 42-14 victory over the Norfolk Spartans on Saturday. -

Humanitarian Imperialism: Using Human Rights to Sell War

Bricmont, J. (2006). Humanitarian imperialism: Using human rights to sell war. New York: Monthly Review Press. Preface to the English Edition Two sorts of sentiments inspire political action: hope and indignation. This book is largely the product of the latter sentiment, but the aim of its publication is to encourage the former. A brief and subjective overview of the political evolution of the past twenty years can explain the source of my indignation. The collapse of the Soviet Union can be compared to the fall of Napoleon. Both were the product of major revolutions whose ideals they symbolized, rightly or wrongly, and which they defended more or less effectively while betraying them in various ways. If their natures were complex, the consequences of their fall were relatively simple and led to a general triumph of reaction, with the United Stales today playing a role analogous to that of the Holy Alliance nearly two centuries ago.1 There is no need to be an admirer of the Soviet Union (or of Napoleon) to make this observation. My generation, that of 1968, wanted to overcome the shortcomings of the Soviet system, but certainly did not mean to take the great leap backwards which actually took place and to which, in its overwhelming majority, it has easily adapted.2 A discussion of the causes of these failures would require several books. Suffice it to say that for all sorts of reasons, some of which will be touched on in what follows, I did not follow the evolution of the majority of my generation and have preserved what it would call my youthful illusions, at least some of them. -

M N Times Oder

MODERN TIMES MODERN MODERN “In Modern Times, Cathy Sweeney gives TIMES us fables of the present that are funny, A woman orders a sex doll vertiginous and melancholy.” for her husband’s birthday. —David Hayden MODERN A man makes films without “ Cathy Sweeney’s stories have already a camera. A married couple lives in attracted a band of fanatical devotees, and Cathy Sweeney take turns to sit in an electric Dublin. She studied at this first collection is as marvellous as we could CATHY SWEENEY chair. Cathy Sweeney’s Trinity College and taught have hoped for. A unique imagination, a brilliant debut.” TIMES wonderfully inventive English at second level for —Kevin Barry debut collection offers many years before turning snapshots of an unsettling, to writing. Her work has “I loved this collection. It vibrates with a glorious strangeness! Magnificently weird, hugely dislocated world. Surprising been published in various entertaining, deeply profound.” “ and uncanny, funny and magazines and journals. Magnificently weird, —Danielle McLaughlin hugely entertaining.” transgressive, these stories Danielle McLaughlin only look like distortions of reality. The Stinging Fly Press, Dublin www.stingingfly.org CATHY SWEENEY “A unique imagination, “Funny, vertiginous a brilliant debut.” and melancholy.” Kevin Barry David Hayden The Stinging Fly Cover Design: Catherine Gaffney Author Photo: Meabh Fitzpatrick RIGHTS GUIDE LONDON 2020 ROGERS, COLERIDGE AND WHITE LTD. 20 Powis Mews London W11 1JN Tel: 020 7221 3717 Fax: 020 7229 9084 www.rcwlitagency.com Twitter: -

Rat Park the Radical Addiction Experiment

7 Rat Park THE RADICAL ADDICTION EXPERIMENT In the 1960s and 1970s scientists conducted research into the nature of addiction. With animal models, they tried to create and quantify crav- ing, tolerance, and withdrawal. Some of the more bizarre experiments involved injecting an elephant with LSD using a dart gun, and pump- ing barbiturates directly into the stomachs of cats via an inserted catheter. With cocaine alone, overfive hundred experiments are still per- formed every year, some on monkeys strapped into restraining chairs, others on rats, whose nervous system so closely resembles ours that they make, ostensibly, reasonable subjects for the study of addiction. Almost all animal addiction experiments have focused on, and concluded with, the notion that certain substances are irresistible, the proof being the animal's choice to self-administer the neurotoxin to the point of death. However, Bruce Alexander and coinvestigators Robert Coambs and Patricia Hadaway, in 1981, decided to challenge the central premise of addiction as illustrated by classic animal experiments. Their hypothesis: strapping a monkey into a seat for days on end, and giving it a button to push for relief, says nothing about the power of drugs and everything about the power of restraints—social, physical, and psychological. Their idea was to test the animals in a truly benevolent environment, and to see whether addiction was still the inevitable result. If it was, then drugs deserved to be demonized. If it wasn't, then perhaps, the researchers suggested, the problem was not as much chemical as cultural. know a junkie. Emma is her name. -

Snake, Rattle, and Roll Transcript

1 Snake, Rattle, and Roll Transcript Tyler: This episode of Lost Highways is being released by History Colorado as many of us are staying home in an effort to keep our community safe during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. To those of you out there who are unable to stay home, whether it’s because you’re working to keep people safe, provide healthcare, or provide supplies, thank you. Underwriting: Lost Highways, from History Colorado, is made possible by the Sturm Family Foundation, proud supporters of the humanities and the power of storytelling, for more than twenty years. [Music] Tyler: In 1979, curator and historian Peggy Ford Waldo had just started working at the Greeley History Museum, when she stumbled upon a mysterious artifact, buried away in storage. Peggy Ford Waldo: And hanging in our very tiny collections storage area was a dress made of the skins of rattlesnakes and it was just protected with a dry cleaner's bag. Noel: A dress made of RATTLESNAKE SKINS. Naturally, Ford Waldo, who you might remember from some of our previous episodes about Dearfield and Native American Mascots, was curious. Peggy Ford Waldo: It looks like a flapper dress. And of course, a dress made of snake skins with the hem of the dress being all the rattles of these skins intact, would have been in for a great time. You know, let's shake, rattle and roll. Tyler: And it wasn’t just a dress. Along with it was an ENTIRE flapper outfit made of snake skins and rattles, including accessories. Peggy Ford Waldo: There was a pair of shoes that had been covered with rattlesnake skins and there was a headband with very large rattles glued all the way around it.