Trade in Air Transport Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004-2005 Highlights 1 1.1 Gradual liberalization in international air services each by winter 2005. UK carriers have also been has been a continuous process with the basic granted access to Bangalore, Hyderabad and Cochin objective of meeting the increasing demand for besides the 4-metro destinations and Indian carriers travel on international routes. Increased to Glasgow, Edinburgh and Bristol in addition to connectivity, greater capacity and more choices for London, Manchester and Birmingham. passengers have a direct bearing on economic growth, apart from meeting the needs of business, Entitlements on India-Australia sector will also be trade and tourism. This process was continued enhanced from the existing 2100 seats/week to 6500 through several initiatives taken during the year. seats/week over the next two years. Australian carriers will also get access to Chennai, Bangalore Some of the major initiatives taken during the year are:- and Hyderabad as additional points over this period. • Revised Air Service Agreement with USA: Entitlements on India-France sector have been As per revised Air Services Agreement, both increased to 35 weekly services effective countries can designate any number of airlines Summer 2005 from 14 weekly services. French and can operate any number of services from carriers will have access to three additional any point in the home country to any point in points in India namely Bangalore, Chennai and the territory of other Contracting State with full Hyderabad. Indian carriers will be able to intermediate and beyond traffic rights. commence 5th Freedom beyond rights to/from • Liberalization of Entitlements with UK, Australia new points in North America from designated and France: points in France. -

PDF Download

Frontierswww.boeing.com/frontiers FEBRUARY 2010 / Volume VIII, Issue IX Capturing the Dream The 787 Dreamliner lifts off from Paine Field, Washington, 10:27 a.m. Pacific time, December 15, 2009 BOEING FRONTIERS / FEBRUARY 2010 BOEING FRONTIERS / FEBRUARY 2010 / VOLUME VIII, ISSUE IX On the Cover Slipping the bonds It’s not often an all-new Boeing jetliner makes12 that magical first flight. It happened Dec. 15 when the 787 Dreamliner completed its takeoff roll at Paine Field near Everett, Wash., and lifted off into an overcast morning before an audience of several thousand Boeing employees. They cried, cheered, and pumped fists and arms in the air—and took a lot of pictures. In this issue, Frontiers celebrates the 787’s first flight with 10 pages of photos taken by employees and by Boeing photographers. COVER IMAGE: AMONG THE BOEING EMPLOYEES WITH A FRONT-ROW SEAT TO HISTORY AT PAINE FIELD IN EVERETT, WASH., DEC. 15, WAS SCOTT WIERENGA, AN ENGINEER ON THE 787 INTERIORS INTEGRATION TEAM. THIS IS HIS PHOTO OF THE MOMENT WHEN THE 787 DREAMLINER FIRST TOOK TO THE SKY. PHOTO BY SCOTT WIERENGA/BOEING PHOTO: THE 787 DREAMLINER, WITH ONE OF TWO CHASE PLANES at ITS SIDE, CLIMBS away FROM PAINE FIELD ON ITS FIRST FLIGHT. KEVIN BROWN/BOEING Ad watch The stories behind the ads in this issue of Frontiers. Inside cover: Inside back cover: Back cover: The “One partnership. Endless Featuring the most popular sport in This ad shows the traditional Indian possibilities” advertising campaign India, cricket, this ad underscores competition of boat racing, which illustrates Boeing’s commitment to the strong partnership between symbolizes the use of teamwork success through its partnership with Boeing and India with the common and the sharing of common goals. -

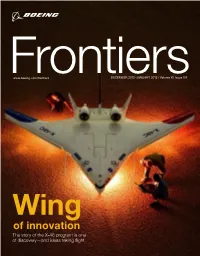

Of Innovation the Story of the X-48 Program Is One of Discovery—And Ideas Taking flight

Frontierswww.boeing.com/frontiers DECEMBER 2012–JANUARY 2013 / Volume XI, Issue VIII Wing of innovation The story of the X-48 program is one of discovery—and ideas taking flight PB BOEING FRONTIERS / DECEMBER 2012–JANUARY 2013 1 BOEING FRONTIERS / DECEMBER 2012–JANUARY 2013 Ad watch On the Cover The stories behind the ads in this issue of Frontiers. Inside cover: This ad was developed to run in the Middle East, a key market for the Boeing 777 jetliner with more operating there than in any other region in the world. Page 6: Highlighting the combined capabilities of Boeing’s Super Hornet and Growler military aircraft, this ad is running in U.S. trade and congressional publications. Pages 10–11: This is the first ad in a new campaign, “Partners Across Generations,” celebrating the relationship between Boeing and China’s aviation industry. Translation: The memorable glamour of [Shanghai’s famous] Bund over time as a Boeing flies over. For over 40 years, Boeing has been supporting the development of the Chinese aviation industry. Boeing is proud of every achievement in this partnership, which transcends time. Pages 14–15: “Enduring Force,” featuring the V-22 tilt-rotor aircraft, focuses on Boeing’s military aircraft expertise. It is one of several ads in a Boeing Defense, Space & Security campaign highlighting the capabilities Boeing brings to 20 its customers. The ads are running in print and online The right blend business, political and trade publications. On a dry lake bed in the high desert of California at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, Boeing and NASA are testing an unusual-looking aircraft. -

Vayu Issue IV July Aug 2015

IV/ 2015 Aerospace & Defence Review Airline of the Preserving the (Aerial) Thunder Dragon Lifeline Airbus Innovation Paris Air Show 2015 Days 2015 St Petersburg Helicopters for India Maritime Show When you absolutely have to get there NOW Enemy aircraft in restricted airspace: ‘SCRAMBLE’ The EJ200 engine provides so much thrust that it can get the Typhoon from ‘brakes o ‘ to 40,000 feet in under 90 secs. When it matters most, the EJ200 delivers. The engine‘s advanced technology delivers pure power that can be relied on time and again. Want to make sure your next mission is a success? Choose the EJ200. The EJ200 and EUROJET: Making the di erence when it counts most Visit us at www.eurojet.de EJ_Ad_VAYU_215x280.indd 1 08/07/2015 15:34:46 IV/ 2015 IV/ 2015 Aerospace & Defence Review Airline of the “complete confidence” in the A400M Paris Air Show 2015 36 which was vigorously demonstrated in 75 Thunder Dragon flight at Le Bourget. Meanwhile, there are several new operators of the C295 medium transport aircraft and the A330 MRTT has also been selected by the Airline of the Preserving the (Aerial) Republic of Korea. Thunder Dragon Lifeline Airbus Innovation Paris Air Show 2015 Days 2015 St Petersburg Helicopters for India Maritime Show 58 A Huge Wish List Artist’s dramatic imaging of Drukair Airbus A319s in Bhutan (Painting by Priyanka Joshi) This Vayu on-the-spot report of the 51st Paris Air Show highlights the key events at Le Bourget in mid- EDITORIAL PANEL June, even though the ‘fizz’ seemed to have gone, with non-participation MANAGING EDITOR of some major firms and a subdued Vikramjit Singh Chopra air display. -

Buying Vs Leasing an Aircraft - a Case Study

ISSN No. 2349-7165 Buying Vs Leasing an Aircraft - A Case Study Dr. M. Ramesh Professor, Dept, of Business Administration, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar 608 002. e mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Airlines need an enormous range of expensive equipment and facilities more than any other service business, from fleet to flight simulators and maintenance hangars. Because of this, the airline industry is a capital intensive business requiring large amount of money to operate effectively. Most equipment are financed through loans or leasing. Due to financial burden of purchasing the aircraft, airlines are using leasing option. This paper analyses the decision made by government owned airline in India for buying/leasing an aircraft. Conclusion is drawn based on the high advantages with respect to purchase value and leasing value by applying Schall model. Keywords: Aircraft, leasing, buying, NPV, NAL, cost, replacement. INTRODUCTION Now a days people travelling by air has greatly increased because of its comfort and fastness. The airtransport industry carry 2,225 million passengers and 54 million tonnes of freight and it is one of the world's most important industries. There are a lot of employment opportunities for millions of people in air travel industry like pilots, stewards, mechanic, customer service representatives and designers. Also travel industry offers indirect jobs like airline catering, car rental, airport retail services, financial services and security. Recent survey says that air transport industry generates 29 million jobs directly and indirectly all over the world and it contributes US$ 2,960 billion that is equivalent to 8% of world GDP. There is a saying in the transport industry that if it flies or floats, you should rent it. -

Aerospace & Defence Review the Indian Navy Today

VI/2017 Aerospace & Defence Review The Indian Navy Today Interview with the CNS HMS Queen Elizabeth The Final Reckoning ? MBDA’s future plans Carrier borne fighters Dubai Air Show 2017 CELEBRATING A PROUD HISTORY OF PARTNERSHIP AS WE FACE TOMORROW’S CHALLENGES TOGETHER www.rafael.co.il VI/2017 VI/2017 Aerospace & Defence Review 36 ‘Fully Capable and 52 Indian Navy’s quest for 72 Dazzle over the Always Ready’ a carrier borne fighter Desert The Indian Navy Today Interview with the CNS HMS Queen Elizabeth The Final Reckoning ? MBDA’s future plans Carrier borne fighters Dubai Air Show 2017 Cover : INS Vikramaditya with fleet support vessel at Sea (photo : Indian Navy) Dan Gillian, Boeing Vice President, F/A-18 and EA-18 programmes, writes on the Super Hornet in context of the EDITORIAL PANEL Indian Navy’s requirement for a carrier MANAGING EDITOR borne fighter and elaborates on key In this on-the-spot report, Vayu features of the Block III Super Hornet. Vikramjit Singh Chopra editors review aspects of the recently concluded Dubai Air Show, with record EDITORIAL ADVISOR “Life on an Ocean’s orders announced including mammoth Admiral Arun Prakash 57 deals for both Airbus and Boeing. Wave” Highlights of the Show are included. EDITORIAL PANEL Pushpindar Singh On the eve of Indian Navy Day 2017, ‘Brilliant Arrow 2017’ Air Marshal Brijesh Jayal Vayu interviewed with Admiral Sunil 114 Dr. Manoj Joshi Lanba on a range of issues and was assured that the Indian Navy is fully Lt. Gen. Kamal Davar capable of tackling all the existing and Lt. -

Competitiveness of the EU Aerospace Industry with Focus On: Aeronautics Industry

FWC Sector Competitiveness Studies - Competitiveness of the EU Aerospace Industry with focus on: Aeronautics Industry Within the Framework Contract of Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054 Final Report Client: European Commission, Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Munich, 15 December 2009 Disclaimer: The views and propositions expressed herein are those of the experts and do not necessar- ily represent any official view of the European Commission or any other organisations mentioned in the Report ECORYS Nederland BV P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 00 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 ECORYS Macro & Sector Policies T +31 (0)10 453 87 53 F +31 (0)10 452 36 60 Table of contents 1 Introduction 19 1.1 Previous Work 19 1.2 Particularities of the Industry 20 1.3 Historical Evolution of the Industry 23 1.3.1 Horizontal Evolution of the Industry 23 1.3.2 Vertical Evolution 25 1.4 Business Cycles in the Aerospace Industry 26 2 The Quantitative Analysis of the European Aerospace Industry 31 2.1 The Sectoral Analysis of the European Aerospace Industry 32 2.1.1 The Development and Performance of the Aerospace Industry 33 2.1.2 The Structure of the Industry 36 2.1.3 Performance Comparison to the Total European Economy 37 2.1.4 The Regional Distribution of the European Aerospace Industry 39 2.1.5 The Intra-European Trade Relations of the European Aerospace Industry 46 2.1.6 The Extra-European Trade of the Aerospace -

Indigo and Air India-- on Wednesday Announced

1 Revue de presse février 2020 The only two Indian carriers that fly to China -- IndiGo and Air India-- on Wednesday announced suspension of most of their flights to that country, while India has requested China for permission to operate two flights to bring back its nationals from Hubei province which has been sealed after the deadly coronavirus outbreak. A fresh travel advisory asking people to refrain from travelling to China has been issued by the Union government which has ramped up screening across airports, ports and borders, as the virus spread to at least 17 countries. No case of the novel coronavirus has been detected in India, though hundreds of people remain under observation in many states including as many as 806 in Kerala, according to officials. With several airlines based in Asia, North America and Europe restricting operations to the region, the Indian carriers too followed suit. The country's largest airline IndiGo said it has suspended its flights on Bengaluru-Hong Kong route from February 1 and on the Delhi-Chengdu route from February 1 to 20. Similarly, state-run Air India is suspending its flights on Delhi-Shanghai route from January 31 to February 14 and reducing the frequency on Delhi-Hong Kong route to thrice-weekly only in the same time period. IndiGo will, for now, continue to operate the Kolkata-Guangzhou flight which it is "monitoring on a daily basis". The crew of the two airlines working on flights connecting India with South East Asian countries have been asked to wear N95 masks on ground and take other precautions like not visiting public places. -

The Fragile Truce Between the Two Co-Founders O

1 Actualités du transport aérien 1-14 octobre 2019 Revue de presse NEW DELHI : The fragile truce between the two co-founders of InterGlobe Aviation Ltd, which runs budget airline IndiGo, appears to be all but broken, with Rahul Bhatia submitting an arbitration request against Rakesh Gangwal on Tuesday before the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA). IndiGo said in a BSE filing that InterGlobe Enterprises Pvt. Ltd (IGE Group) and Rahul Bhatia have submitted a request for arbitration to the LCIA under the shareholder agreement of InterGlobe Aviation on 23 April 2015 between the IGE Group and Rakesh Gangwal Group (RG Group) which comprises Gangwal, the Chinkerpoo Family Trust and Shobha Gangwal. “The company (InterGlobe Aviation) has been named as a respondent, as it is a party to the shareholder agreement," IndiGo said. The development follows Gangwal reaching out to the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) on 30 August, seeking directions on issues ranging from related-party transactions (RPTs) and chairman M. Damodaran’s conduct to curbing Bhatia-owned IGE’s “unusual controlling rights". Gangwal and his associates hold nearly 37% in InterGlobe Aviation, while IGE group owns around 38%. Although the two groups own similar stakes, an initial agreement gave special rights to Bhatia’s company. On 27 August, Mint reported that Gangwal had agreed to support the proposed changes at an annual general meeting after some of his demands, including on board expansion and RPTs, were accepted, ending months of public wrangling. With both promoters refusing to back down, the dispute may prove to be a costly distraction for the airline, which dominates Indian skies with nearly 50% market share. -

Indian Aviation Is Having a Lesser Number of Aircraft. » 'Besides The

1 Revue de presse du 15 au 31 mars 2019 « Indian aviation is having a lesser number of aircraft. » 'Besides the Boeing 737 MAX, you have the A320Neos which Indigo is currently grappling with because of a lack of pilots.' 'This has led to cancellation (of flights) and therefore the prices of air tickets are on the higher side this season although generally in March ticket prices are on the lower side.' After an Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 MAX crashed on March 10 killing all 157 on board, the Boeing 737 MAX has been grounded by all the nations it was in operation, including India. The Ethiopian Airlines crash was the second crash involving Boeing 737 MAX aircraft in five months. On October 30, 2018, an Indonesian Lion Air three-month-old Boeing 737 MAX 8 crashed, killing 189 crew and passengers including its Indian pilot Bhavye Suneja. The grounding of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft -- affecting SpiceJet and the beleaguered Jet Airways in India -- has led to a raft of flight cancellations, airfares heading north and major inconvenience posed to fliers. Can the crisis be resolved? With the 737 MAX fly again? What should the Indian government do to alleviate the pain for fliers? "The grounding of these Boeing aircraft will affect global aviation more than the Indian aviation industry," Sankalp Sinha, director of aviation consultant and Indian advisory, research, at Martin Consulting LLC, tells Rediff.com's Syed Firdaus Ashraf. How severe is the crisis facing Indian aviation after the DGCA decided to ground Boeing 737 MAX aircraft? In the long term, whenever a manufacturer releases a new aircraft in the market, these teething troubles are bound to happen. -

Analysis: a Decade of Incredible LCC Growth in India: Routesonline

1 Analysis: A decade of incredible LCC growth in India: RoutesOnline As SpiceJet and IndiGo move to fill the capacity void left by Jet Airways, we look at India's dramatic shift to LCCs over the past ten years. The news that Jet Airways would be suspending all flights after failing to attract additional funding was no surprise, following a series of suspensions and service changes in April and March. In the subsequent rush to fill the void SpiceJet and IndiGo have proven to be the most active in the early stages. And though the government has pledged to support the embattled carrier, amid the backdrop of a dramatic power shift to LCCs in India’s domestic market it’s unlikely that it will ever recover to its previous levels of service. To better understand the market in which India’s carriers have been operating over the last decade, Routesonline had a close look at the data behind the incredible LCC growth story. Incredible growth of LCCs Since 2009 the expansion in Indian flight capacity has made it consistently one of the world’s fastest-growing markets. In total the number of available departure seats has more than doubled, swelling by 114.5 percent to 206 million in 2018. However the growth in mainline carriers has been much more modest, rising just 20.7 percent from 67.1 million to 80 million over the decade. While ten years ago the mainline carrier market dwarfed that of LCCs, with 2.3 times more seats available, LCC capacity has grown by an incredible 331.9 percent during the period to reach 125million. -

Organization Study at Air India Ltd

ORGANIZATION STUDY AT AIR INDIA LTD This project report has been prepared after one month period of in plant training at Air India Ltd a study of Air India Ltd as a whole and its various departments in detail. The main objective of this study is to understand how the organization really works and to get a practical knowledge. The study started with company profile and organization structure of Air India Ltd. Each and every functional department studied individually in detail they are: Finance department, Personnel department, Commercial department, Ground support department, Operations department, Engineering department and Materials management department. Each department plays a very important role in every organization and they are dependent on each other. The study of functional departments started with Finance department. In Finance department the manager was cooperative and friendly. He gave me last 5 years annual report to understand the growth of the company and explained various functions and designation in Finance department. In Personnel department the manager explained various functions and policies. She also explained about various sections under Personnel department. Commercial department provides various services to passengers and cargo. It also includes public relations. The various promotion tools adopted by Air India Ltd were studied. During one month studied all the departments in detail with the help and co-operation of the employees of the company. I interacted with the employees of Air India Ltd and a lot of relevant information was collected for preparing this report. Based on this information SWOT analysis is prepared. The study gave me an insight about the work environment and the operations involved in the organization.