WTPP 5/4.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

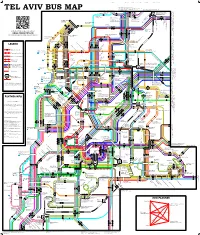

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

BIG SHOPPING CENTERS BIG Shopping Centers Ltd

BIG 1 BIG SHOPPING CENTERS BIG Shopping Centers Ltd. ("BIG") - headquartered in Herzelia, Israel - was founded in 1994 by Yehuda Naftali with the vision of developing American styled open-air shopping centers in Israel. Today, the company operates in three countries - Israel, the United States and Serbia - where it has ownership (entire or partnership) in 58 projects, 51 of them being operational shopping centers and 7 under development. BIG is a publicly traded company, traded on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, and listed in the TA 100 Index (top 100 companies in the stock exchange). The company was traded on the TASE on May 2016 at over $700 million, and it's total balance sheet assets on December 31, 2015 was at $1.995 billion. *Values in this book were derived from an exchange rate of 3.75 NIS/1 $US BIG 2 BIG 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 BIG'sTeam 10 Company Overview 22 Our Partners 26 Property Portfolio 64 Financial Data 70 Our Goals BIG 5 Yehuda Naftali | Chairman of the Board & Founder Mr. Naftali has an active role in navigating the company, and setting its goals and strategies. Mr. Naftali has over 40 years' of experience in the business of site location, construction and management of open air shopping centers. His real estate career began in West Hollywood and West Los Angeles developing and redeveloping commercial properties for retailers. Eitan Bar Zeev | Director & C.E.O Mr. Bar Zeev serves as the principal leadership role for the execution of BIG's overall business strategy, and brings a variety of experience in all aspects of retail, marketing, acquisitions and brand building. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Sukkot Real Estate Magazine

SUKKOT 2020 REAL ESTATE Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Living the high Life LETTER FROM THE EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Readers, With toWers Welcome to the Sukkot edition of The Jerusalem THE ECONOMY: A CHALLENGING CONUNDRUM ....................08 Post’s Real Estate/Economic Post magazine. Juan de la Roca This edition is being published under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic. Although not all the articles herein are related to the virus, it is a reality BUILDING A STRONGER FUTURE ............................................... 12 that cannot be ignored. -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel

Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel המרכז הרפורמי לדת ומדינה -לוגו ללא מספר. Third Annual Report – December 2013 Israel Religious Action Center Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel Third Annual Report – December 2013 Written by: Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation: Attorney Einat Hurwitz, Attorney Orly Erez-Lahovsky English translation: Shaul Vardi Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, Haaretz, September 29, 2010 – © Haaretz Newspaper Ltd. © 2014 Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Israel Religious Action Center 13 King David St., P.O.B. 31936, Jerusalem 91319 Telephone: 02-6203323 | Fax: 03-6256260 www.irac.org | [email protected] Acknowledgement In loving memory of Dick England z"l, Sherry Levy-Reiner z"l, and Carole Chaiken z"l. May their memories be blessed. With special thanks to Loni Rush for her contribution to this report IRAC's work against gender segregation and the exclusion of women is made possible by the support of the following people and organizations: Kathryn Ames Foundation Claudia Bach Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation Bildstein Memorial Fund Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation Inc. Donald and Carole Chaiken Foundation Isabel Dunst Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation Eugene J. Eder Charitable Foundation John and Noeleen Cohen Richard and Lois England Family Jay and Shoshana Dweck Foundation Foundation Lewis Eigen and Ramona Arnett Edith Everett Finchley Reform Synagogue, London Jim and Sue Klau Gold Family Foundation FJC- A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds Vicki and John Goldwyn Mark and Peachy Levy Robert Goodman & Jayne Lipman Joseph and Harvey Meyerhoff Family Richard and Lois Gunther Family Foundation Charitable Funds Richard and Barbara Harrison Yocheved Mintz (Dr. -

Exporting Zionism

Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ayala Levin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin This dissertation explores Israeli architectural and construction aid in the 1960s – “the African decade” – when the majority of sub-Saharan African states gained independence from colonial rule. In the Cold War competition over development, Israel distinguished its aid by alleging a postcolonial status, similar geography, and a shared history of racial oppression to alleviate fears of neocolonial infiltration. I critically examine how Israel presented itself as a model for rapid development more applicable to African states than the West, and how the architects negotiated their professional practice in relation to the Israeli Foreign Ministry agendas, the African commissioners' expectations, and the international disciplinary discourse on modern architecture. I argue that while architectural modernism was promoted in the West as the International Style, Israeli architects translated it to the African context by imbuing it with nation-building qualities such as national cohesion, labor mobilization, skill acquisition and population dispersal. Based on their labor-Zionism settler-colonial experience, -

Tel-Aviv Metro M1 North Assessment of NTA Planning

Tel-Aviv metro M1 North Assessment of NTA planning for The region of Drom Hasharon and the municipalities of Herzliya – Kfar Saba – Raanana – Ramat Hasheron doc.ref.: M1-North-Planning-NTA-Assessment-v06.docx version: 0.6 date: 18-01-2021 author: Dick van Bekkum Copyright © 2020/2021 MICROSIM Maisland 25 3833 CR Leusden The Netherlands Assessment of NTA plans M1 North Contents 0. Assessment Statement ............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Planning of M1 .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Assessment of plans ........................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Technical assumptions ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Structure of this document ................................................................................................... 6 2. Construction technology and logistics ....................................................................................... 6 3. Noise and vibration................................................................................................................... 6 4. Electro Magnetic Compatibility ................................................................................................. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

Tel Aviv Exercising Modernity the Organizer

Tel Aviv exercising modernity The Organizer Communities & the commons The Pilecki Institute in Warsaw is a research and cultural institution whose main aim Tel Aviv, Israel is to develop international cooperation and to broaden the fields of research and study 24—29.10.2019 on the experiences of the 20th century and on the significance of the European values – democracy and freedom. The Institute pursues reflection on the social, historical and cultural transformations in 20th century Europe with a particular focus on the processes which took place in our region. The patron of the Institute, Witold Pilecki, was a witness to the wartime fate of Poles and himself a victim of the German and Soviet totalitarian regimes. From today’s perspective, Pilecki’s story can prompt us to rethink the Polish experience of modernity in its double aspect: both as the one that brought destruction on Europe and that which continues to serve as an inspiration for promoting freedom and democracy throughout the continent. Under the “Exercising modernity” project, the Pilecki Institute invites scholars and artists to reflect upon modern Europe by studying the beginning and sources of modernity in Poland, Germany and Israel, and by examining the bright and dark sides of the 20th century modernization practices. Organizer Partners Our Partners in Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Our Partners in Tel Aviv Venues & accommodation The Liebling House – White City Center The Liebling Haus White City Center The White City Center (WCC) was co-founded 29 Idelson Street by the Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality and the German government at a historical Hostel Abraham and cultural crossroad in the heart 21 Levontin Street of Tel Aviv. -

Autonomous Vehicle (AV) Policy Framework, Part I: Cataloging Selected National and State Policy Efforts to Drive Safe AV Development

Autonomous Vehicle (AV) Policy Framework, Part I: Cataloging Selected National and State Policy Efforts to Drive Safe AV Development INSIGHT REPORT OCTOBER 2020 Cover: Reuters/Brendan McDermid Inside: Reuters/Stephen Lam, Reuters/Fabian Bimmer, Getty Images/Galimovma 79, Getty Images/IMNATURE, Reuters/Edgar Su Contents 3 Foreword – Miri Regev M.K, Minister of Transport & Road Safety 4 Foreword – Dr. Ami Appelbaum, Chief Scientist and Chairman of the Board of Israel Innovation Authority & Murat Sunmez, Managing Director, Head of the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Network, World Economic Forum 5 Executive Summary 8 Key terms 10 1. Introduction 15 2. What is an autonomous vehicle? 17 3. Israel’s AV policy 20 4. National and state AV policy comparative review 20 4.1 National and state AV policy summary 20 4.1.1 Singapore’s AV policy 25 4.1.2 The United Kingdom’s AV policy 30 4.1.3 Australia’s AV policy 34 4.1.4 The United States’ AV policy in two selected states: California and Arizona 43 4.2 A comparative review of selected AV policy elements 44 5. Synthesis and Recommendations 46 Acknowledgements 47 Appendix A – Key principles of driverless AV pilots legislation draft 51 Appendix B – Analysis of American Autonomous Vehicle Companies’ safety reports 62 Appendix C – A comparative review of selected AV policy elements 72 Endnotes © 2020 World Economic Forum. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. -

The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel March 2011

The Inequality Report The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel March 2011 The Inequality Report: The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel ADALAH – THE LEGAL CENTER FOR ARAB MINORITY RIGHTS IN ISRAEL 94 Yaffa Street, PO Box 8921, Haifa 31090, Israel Tel: +972 4 950 1610 – Fax: +972 4 950 3140 Adalah Email: [email protected] The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel Website: www.adalah.org Principle author Katie Hesketh Additional authors Suhad Bishara, Advocate Rina Rosenberg, Esq. Sawsan Zaher, Advocate Design UnderGround Studio ISBN: 978-965-90512-3-6 Three videos accompany this report: Targeted Citizen; Targeted Citizen – Unrecognized Villages Case; and Targeted Citizen – Israel Railways Case. These videos are available on the website of Adalah and Adalah’s YouTube page. The videos were written and directed by Rachel Leah Jones. This report and the three videos together comprise “The Inequality Series”. Adalah wishes to thank Christian Aid for its financial support to this project. The contents of the videos and this document are the sole responsibility of Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the official position of Christian Aid. March 2011 Adalah also appreciates the generous contributions of the following foundations Inequality Report: and institutions to our work: The Ford-Israel Fund; OxfamNOVIB; The Open Society Institute Development Foundation; The New Israel Fund; The European Union; The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel Evangelischer Entwicklungsdienst (EED); The Federal Department of Foreign Affairs December 2010 - Switzerland; The Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation; Broederlijk Delen; The Sigrid Rausing Trust; and The NGO Development Center. -

2 Palestine Logistics Infrastructure

2 Palestine Logistics Infrastructure Seaports The Port of Ashdod - just 40 km from Tel Aviv, it is the closest to the country's major commercial centres and highways. Ashdod Port has been operating since 1965 and is one of the few ports in the world built on open sea. The Port of Haifa - the Port of Haifa is the largest of Israel's three major international seaports, which include the Port of Ashdod, and the Port of Eilat. It has a natural deep-water harbour which operates all year long and serves both passenger and cargo ships. The Port of Haifa lies to the north of Haifa's Downtown quarter at the Mediterranean and stretches to some 3 km along the city's central shore with activities ranging from military, industrial and commercial aside to a nowadays-small passenger cruising facility. The Port of Eilat - the Port of Eilat is the only Israeli port on the Red Sea, located at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. It has significant economic and strategic importance. The Port of Eilat was opened in 1957 and is today mainly used for trading with Far East countries as it allows Israeli shipping to reach the Indian Ocean without having to sail through the Suez Canal. International airports There are two international airports operational in Israel, managed by theIsrael Airports Authority.Ben Gurion Airportserves as the main entrance and exit airport in and out of Israel.Ramon Airportbeing the second largest airport serves as the primarydiversion airportfor Ben Gurion Airport. Road and Rail Transport Roads - Transportation in Israelis based mainly on private motor vehicles and bus service and an expanding railway network.